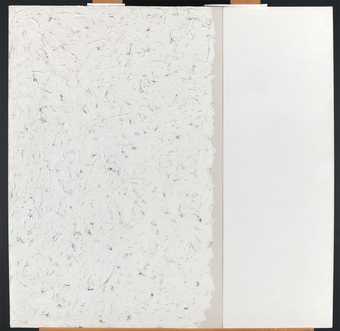

Robert Ryman

Untitled 1960

Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam

Photo: René Gerritsen Art Research Photography, 2017

In addition to the work being conducted on model paint systems (paint reconstructions), the CMOP research group also investigate ‘real’ paintings from the collections of the partner institutions and associated partners, such as the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, the Gemeentemuseum in The Hague or Tate.

The results from these types of ‘case study’ research projects are then published in order to provide much needed information for those conservators that are confronted with similar treatment challenges and artworks. One case study is a largely monochrome white painting from 1960 by Robert Ryman from the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam.

Ryman is an American painter who worked in New York between the 1950s to the early 2010s. His works are often associated with monochrome art, minimalism and conceptual art – though he does not agree with this and rather calls himself a ‘realist painter’.1

According to him, in his paintings there is no illusion, no narrative, no myth and the aesthetic experience is real. Ryman equates vocal music with representational art, and instrumental music with abstract art.2 He denies that his works are monochromes,3 saying that white can be warm or cold and that there are many shades of white.

The artist is very clear about the fact that his paintings may never be framed and glazed and must hang directly on the wall. This means that dust from the environment comes directly into contact with the unvarnished surface of the painting and will become duller over time. Because there is no image to look at, the loss of surface gloss nuances due to dirt deposition, as well as the change in colour brightness will likely render these works in need of repeated cleaning treatments.

Before cleaning artworks not only are the appearance, materials, their application technique and degradation properties investigated and documented, but also the concept and meaning of the work, often referred to as the ‘artistic intent’. Understanding the material as well as the immaterial aspects of a painting enables conservators to make treatment decisions that are crucial to the retention of both the conceptual understanding and material integrity of the work.

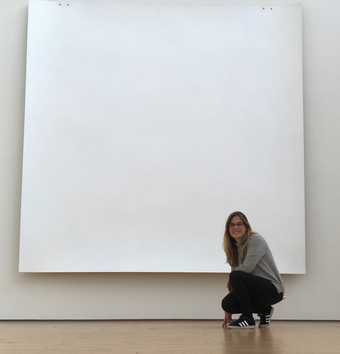

Our proximity to the ‘original’, particularly for modern and contemporary art, creates an urgency to document this appearance before too much ageing occurs. Visual documentation of paintings is particularly difficult in cases where works are monochrome and where the preservation of the original surface appearance is paramount. Ryman’s paintings are virtually impossible to document using photography. They lose their depth and charm in reproductions. In order to really understand these subtle works, the viewer needs to move in front of them and experience the nuances in reflection and light absorption of the various painted surfaces.

John Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, 2017

In order to better understand and document Ryman’s paintings, I visited the Getty Conservation Institute (GCI) in Los Angeles, which is one of CMOP’s associate partners. In 2009 the GCI had sampled forty-five paintings and conducted an artist interview with Ryman in his studio. Together they discussed not only his materials and application techniques, but also his attitudes towards the conservation treatment and cleaning of his works.4

From this interview it can be deduced that Ryman is quite lenient when it comes to slight soiling and tonal changes in the paints. Yet he mentions that, even though ageing is ‘only natural’, the works shouldn’t change ‘too much’. This subjectivity naturally makes it difficult for the individual conservator to establish how much is ‘too much’.

In 1992 the MoMA and Tate held a large Ryman exhibition which was shown at both venues. Ryman was present at the installation of the New York show. At that time he approved of the appearance of all of his works, even though some were more than thirty years old and had not undergone overall cleaning treatments other than light dusting.

Lise Steyn in front of Robert Ryman’s Consort 1988, DIA:Beacon, December 2017

Artist interviews such as this have proven to be of immense value to conservators. Seeing the artist discuss conservation issues, hearing his intonation and seeing his gestures and attitude towards his artworks gives the conservator some guidance for the meaning and importance of the materials of the work that can help guide within their treatment decisions. It must be understood, however, that many other factors also play a role in the final treatment decision and the artist is not interviewed to ask how to restore his works, but rather what meaning they have and what is important long-term about the materials used. In addition to viewing artist interviews, scientists at the GCI compared several paint samples taken from Ryman’s studio with paint samples from the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam work and learned more about the chemical components in the paints used by the artist.

Raking light view of works by Robert Ryman on permanent display at DIA:Beacon, December 2017

Having previously examined Ryman’s paintings in the Netherlands and at Tate in London, I closely examined over fifty of Ryman paintings at several American institutions, starting at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMoMA) and then flying to New York for the second leg of the trip to visit the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), DIA:Beacon, Whitney Museum of American Art, The Metropolitan Museum and Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum.

Private conservators Sandra Amann, Elizabeth Estabrook and Dana Cranmer, who were all students of Ryman’s friend and conservator Orrin Riley, gave interviews on their experiences with the artist and their ways of approaching his work.5 At the Guggenheim Julie Barten discussed her encounters with Ryman and the challenges in conserving and installing his larger works, of which the Guggenheim has several. In New Haven I had the privilege of speaking with Robert Storr, who is an expert and wrote a seminal work on Ryman.6 I also visited the artist’s studio and spoke with David Gray, who is presently working on a catalogue raisonné.

All of this research has resulted in a better understanding of the artist’s intent in creating these paintings, his attitudes towards the materials and their ageing and an overview of the types of conservation treatments he has approved of for his works. Visually inspecting many of his paintings and having described these surfaces in writing where photography fails will contribute to the future understanding of the original appearance of these paintings.

Lise Steyn, CMOP PhD candidate, University of Amsterdam

March 2018