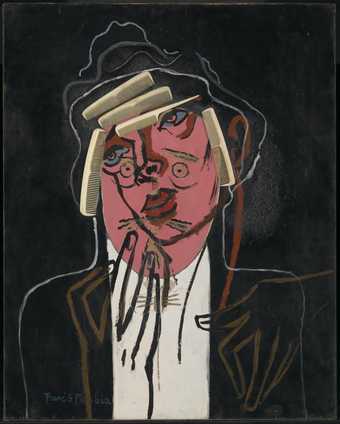

Francis Picabia

The Handsome Pork-Butcher

(c.1924–6, c.1929–35)

Tate

The beginning of the twentieth century in Paris was a turbulent time and a time of rapid development both artistically and technologically. It was also a period of rapidly developing paint technology and improvement in the properties of commercial house paint. New paint formulations abounded and commercial production escalated. Artists began to exploit the properties of these products.

Picasso experimented with new materials including a brand of house paint called Ripolin, for its handling and visual properties, and his influence spread beyond Paris. Picabia took it a step further and appears to have used exclusively Ripolin in some of his works, reportedly deploying it as a political device to snub the conservative, post-war establishment and to undermine the fine art movement.

Most of the paintings by Picasso and Picabia being explored in this project are examples of the artists re-working an earlier image, on occasion applying new paint to the entire surface. While this could be seen as a result of scarcity of materials, this does not seem to be the only motivation for such re-use. In some cases the image beneath is actively incorporated into the upper image, adapting and subverting its previous subject. This is interesting historically as it gives some clues as to the evolution of ideas by each artist and sometimes of a change in direction. Technically, re-working on any scale is significant to the ageing of the works. The differential drying of thick layers of oil paint leads to wrinkling, cracking and splitting of the upper layers, phenomena which have become significant features of the works themselves. For instance, Picasso said that he liked the open cracks in The Three Dancers as they revealed the flesh beneath. They also influence the stability of the works and decisions as to how to conserve them, thus they can play a role in future conservation.

The imaging of paint layers, both visible and hidden to the naked eye, has developed rapidly in recent years and all avenues available will be investigated to look at the paintings in the project, including X-ray and multi-spectral techniques. Layer structure and analysis of materials will also help to inform the order of application and whether layers were applied over a dry substrate or if they were applied wet-in-wet, providing evidence of time scale and artistic method.

Paintings Conservator Annette King had begun research into these works in relation to the Tate Programme, but this generous Fellowship will allow her to bring together previous research, carry out new analysis in collaboration with Tate Conservation Scientists Bronwyn Ormsby and Joyce Townsend and to collaborate with colleagues both at Tate and in other institutions to make important comparisons with other key works. The findings will lead to a range of publications and talks.

The following have all generously shared information and recent research on paintings in their collections by Picabia and Picasso: Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, USA; Comité Picabia, Paris; MoMA New York, USA; National Gallery Washington, Washington DC, USA; Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, USA. There are also generous individuals who have given of their time and expertise.

Further reading

Annette King, Joyce H. Townsend, Bronwyn Ormsby and Gwénaëlle Gautier, ‘The Use of Ripolin by Picabia in The Fig Leaf 1922’, Journal of the American Institute for Conservation, vol.52, no.4, November 2013, pp.246-257. DOI: 10.1179/1945233013Y.0000000015