Fig.1

George Gower c.1540–1596

Elizabeth, Lady Kytson

1573

Oil paint on panel

685 x 522 mm

N06091

The support is an oak panel measuring 685 x 522 mm (fig.1). It is composed of two boards with a vertical join that runs down the painting just to the right of the sitter’s left eye (fig.2). All four outer edges of the panel are beveled at the back, and are badly worn. Dendrochronology undertaken in 2002 revealed that both boards are from the same tree, which was of Baltic/Polish origin. The youngest heartwood ring dates from 1557 and the earliest possible felling date is 1566. Further dendrochronology in 2004 indicated that these boards were not from the same tree as used in the companion portrait of Lady Elizabeth’s husband, Sir Thomas Kytson 1573 (N06090).1

The ground is made from white marine chalk and animal glue. It is about 70 microns thick and was applied smoothly. The ground has had a history of flaking and there are many losses. The priming is opaque, greyish white, composed of lead white tinted with black, brown, opaque red and translucent particles, all bound together in oil.2 Its thickness varies from 1 to 20 microns, reflecting the method of application; it is a solid layer built up of criss-cross brushstrokes that remain visible on the surface where this layer was deliberately left uncovered. It forms the basic white of the sleeves and parts of the bodice; glazed with semi-translucent red paint, it acts as a reflective underlayer for the red gown.

Fig.2

X-radiograph of Lady Kytson

Infra-red reflectography reveals confident linear underdrawing in the face and hands (figs.3 and 4). It was done on top of the priming and describes outlines rather than shading; it marks out the shape and position of the features. As in the companion portrait of Lady Kytson’s husband, the drawing in the face was done with what appears to be a dry carbon point, whereas in her hands the drawing lines appear to have been done with brushed fluid wet medium (fig.4). The carbon underdrawing in the face does not look freehand; perhaps it was done from a drawing from the life on paper. The hands look as if they might have been done from a standard template. Again as in her husband’s portrait, Lady Kytson’s eyes were at first drawn looking directly in front of the sitter, rather than towards the viewer. This early positioning is now visible as dark pentimenti at the side of the final, painted irises.

Fig.3

Infra-red detail of face

Fig.4

Infra-red detail of the gloved hands

Generally the paint is opaque with an enamel-like surface and little discernible brushwork except slightly in the background. The palette is high toned and the features of the face are defined with soft, reddish brown, linear shadows (fig.5). The artist appears to have begun the portrait by laying in the face, the ruff and the costume in shades of reddish brown oil paint, applied sketchily, especially in the face where this underpainting is confined to the shadows. Close examination of tiny losses in parts of the costume of Lady Kytson shows plum and pinkish brown oil underpaint as well as linear drawing (fig.6).

Fig.5

Detail of face, showing smoothly blended, opaque paint and the characteristic ‘oyster’ eye-sockets

Fig.6

A tiny loss of paint in the white sleeve, showing reddish brown underpainting at the base of the paint loss

When this sketchy underpainting was dry, the artist commenced painting the various areas of the portrait, using two basic methods: for the face, gloves and fur trimmings he used a wet-in-wet technique, in which tones were pre-mixed on the palette before being applied to the painting and blended together softly. The curve of eyeball was defined with a stroke of grey paint, applied wet-in-wet into the basic white and highlighted with a stroke of bright greenish blue, which probably contains azurite (fig.7). There is much fine black pigment in the mixtures for the shadows in the face. Additional glazes were used in the shadows or for small details.

Fig.7

Close-up detail of her right eye, showing wet-in-wet addition of blue paint into the white of the eye-ball to create the receding half-shadow. It shows also the first position of the iris and pupil

Elsewhere he used a sequential technique, with orderly layers of opaque paint, which were left to become touch dry before the next coat was applied. Cross-sections show that the background was underpainted with thick, opaque greyish red paint, applied in two coats (figs.8 and 9).

Fig.8

Cross-section through the plum coloured background. From the bottom: white ground, stained pink with Acid Fuchsin to identify the proteinaceous binding medium; thin, opaque, oil-bound, pale grey priming; dark grey underpaint; final coat of plum coloured paint

Fig.9

The same sample as fig.8 photographed in ultraviolet light, showing intermediate varnish layers as fluorescent lines

The hat, ruff and fur trimming were underpainted with opaque mid-grey. The plume’s grey underside was applied on top of the white priming, after which the white lines defining the barbs were put in, on top of it. For the ruff, the artists mixed up light, opaque grey and worked it lightly on top of the darker grey underpaint to describe the pleats (fig.10).

Fig.10

Close-up detail of the ruff, with grey underpaint visible at the base of tiny losses in the final, visible layer

The white tracery paint was applied last. The grey shadows in the sleeve were applied thinly on top of the priming, after which the lines representing blackwork embroidery were added and the opaque white strokes of the gauze applied last (fig.11).

Fig.11

Detail of the sitter’s right sleeve in slightly raking light to show the sequential development of the painting

The exception in terms of opacity is the red in the costume, where translucent paint made from a red lake pigment was applied thickly on top of lightly underpainted priming. The original red glaze has faded and been replaced by a later, non-original glaze, except where the original colour has been protected from light by the rebate of the frame in the lower, right corner (figs.12 and 13).

Fig.12

Detail of the red costume at the lower edge, where it would have been protected by the rebate of the frame. The original red glaze is the brighter strip immediately above the edge. The darker red above it is a modern replacement of the original colour, which had faded from exposure to light

Fig.13

George Gower

Lady Kytson

Close-up detail of the original red glaze at the lower edge

A significant feature of the technique, as in the companion portrait of Lady Kytson’s husband, is the apparent use of intermediate varnishes during the course of painting. The two coats of greyish red undercoat in the background were varnished when dry, after which the final plum coloured layer of paint was applied (figs.8 and 9). It would appear that Gower wanted maximum saturation of his paint, which would help ensure the high key of his colours. This feature occurs also in Gower’s Self Portrait, which is in a private collection.3 Another feature that is common to all three paintings is the distinctive form of the figure 5 in the background inscription: it looks like a ‘6’ with its lower left curve removed (fig.14).

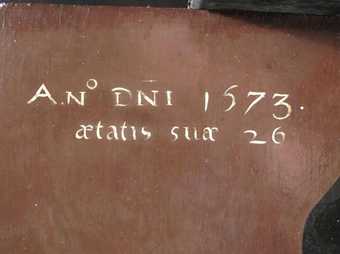

Fig.14

The left-hand inscription in the background

The painting was cleaned at Tate in 1995. During this treatment the conservator noted evidence of several, earlier restoration campaigns. Though much overpaint was removed in 1995, some was left in the face and the non-original re-glazing of the pink costume was also left undisturbed. The new varnish is a modern synthetic resin.

July 2015