Fig.1

Marcus Gheeraerts II 1561 or 2‒1636

Portrait of Mary Rogers, Lady Harington 1592

Oil on panel

1130 x 851 mm

T01872

This painting is in oil paint on an oak panel measuring 1130 x 851 mm (fig.1). The panel is made up of four vertical boards of unequal widths, butt-joined with glue (fig.2). Dendrochronology of the board that contains the face revealed that the oak is of eastern Baltic origin with an earliest felling date of 1586.1 Its earliest tree-ring is from 1386, and its width of 285 mm is close to the typical width for planks from this area. The panel has had a history of splitting. When the join at the right hand side of the main plank split open in the past, the edges of this and the adjoining plank were trimmed before being reglued, in order to achieve a good mend. This resulted in a small loss of image; some of the patterning in the ruff, necklace and dress does not quite match up across the join. This was probably done in the nineteenth century at the time the panel was thinned down to a thickness of around 7 mm in order to be fitted with a wooden cradle to keep it flat and discourage further splitting within the planks. In the event the cradle promoted other splits in the wood. It was therefore removed in the 1970s to be replaced by a ‘parquet’ support of balsawood blocks, cut across the grain and attached to the back of the panel with a reversible adhesive.

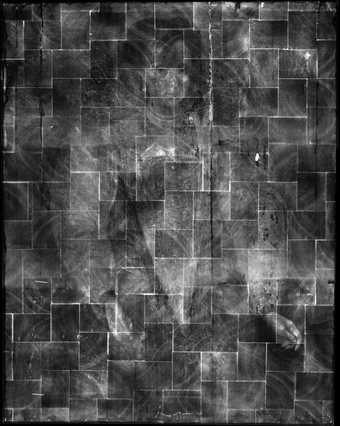

Fig.2

X-radiograph of Mary Rogers, Lady Harington 1592. The white, rectilinear lines are the edges of the modern balsawood blocks supporting the back of the panel and the swirls throughout the image are the adhesive between the blocks and the back of the panel

The ground is white, composed of chalk bound in animal glue and applied smoothly to the panel. It is about 200 microns thick. On top of the ground is a priming of opaque, pale bluish grey. It is composed of lead white with fine charcoal black pigment, bound together in oil. It was applied thinly with vigorous brushstrokes to produce an even thickness and slightly roughened surface, which was left visible as the grey colour of the bodice and sleeves. Over the years this layer has developed very small, spherical protrusions of lead soap aggregates, which are formed through the interaction of the lead white with the oil; some of them have erupted into the paint layers on top (figs.3–4).2

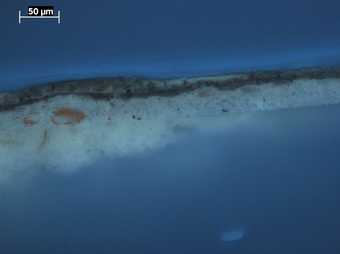

Fig.3

Cross-section through the tablecloth at the right edge, photographed at x320 magnification. From the bottom: white ground; bluish grey priming containing lead soap aggregates; dark brownish grey paint; dark grey paint; varnish

Fig.4

Cross-section through the tablecloth at the right edge, photographed at x320 magnification in ultraviolet light. From the bottom: white ground; bluish grey priming containing lead soap aggregates; dark brownish grey paint; dark grey paint; varnish. The fluorescence of the top layer of paint suggests a resinous additive in the oil

No underdrawing is visible with the eye or infra-red reflectography.3 As is usual in paintings by Gheeraerts on wooden panel, the face and hair were painted thinly, wet-in-wet, whereas the rest of the painting was worked up sequentially in layers. In the face he used thin but opaque mixtures of white lead, vermilion and black particles, with lake and brown added in for the shadows.4 Large, translucent, irregular particles are present throughout. Smalt was mixed with lead white and black for the white of the eyes. The shadows of the features are in cool, opaque, pale brown, with fine vermilion red lines hatched into them. Hatched lines of red lake form the shadow between the vermilion lips. Pink cheeks were worked wet-in-wet into the basic fleshtone. The hair was painted in one brown colour applied in overlapping, graphic scumbles to build up different thicknesses of paint and a sense of texture.

One tone of opaque, matt black was used directly on top of the grey priming for the costume. It was also used for the decorative shapes in the embroidered pattern of the bodice and sleeves. A darker, more translucent black was put in on top to depict the oval black beads, with highlights of pure lead white dotted on to finish. Finally strokes of pure lead white were applied graphically to describe the puffs of fine linen bulging through the blackwork embroidery.

The pearls were applied on top of the black dress with quick, precise swirls of a pale grey opaque paint mixed from lead white, smalt and black. Highlights were applied next: the central catchlight looks like pure lead white, while the curved, reflected light on the side of each pearl is a pale yellow, which looks like a mixture of lead white and lead tin yellow.

The painting was cleaned and restored at Tate in the 1970s; see above for structural work done at the same time.

May 2004