John Michael Wright 1617-1694

Sir Neil O’Neill

1680

Oil paint on canvas

2327 x 1632 mm

T00132

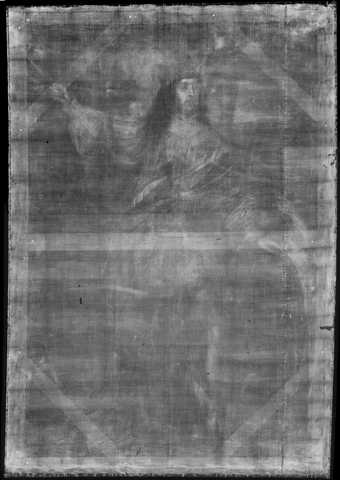

This painting is in oil paint on canvas measuring 2327 x 1632 mm (fig.1). The canvas is made up of two pieces of plain woven linen, joined at an original, stitched, vertical seam approximately 260 mm from the right edge (fig.2). Both pieces of canvas are of the same weight with a weave count of 15–16 threads per square centimetre in the vertical direction and 12–13 in the horizontal. The canvas weave is even with few slubs. There is cusping of the canvas weave on all edges of the composition and the original tacking margins are present on all sides.1 The painting is lined with wax-resin adhesive; this dates from 1959; before that date the painting had a glue-composition lining, which was removed from the painting in order to accommodate the wax-resin lining.

Fig.2

X-radiograph of Sir Neil O’Neill 1680

The pine stretcher is not original and probably relates to the earlier glue-composition lining. It consists of four perimeter bars with single, horizontal cross bar and four corner braces. Stretcher bar marks from an earlier, possibly original stretcher were noted during the delining treatment described above. The outer members forming the rectangle were approximately 75 mm wide; they were braced with two horizontal bars, one across the middle of the painting, the other 30 mm higher. Delining revealed two original inscriptions in the lower half of the back of the original canvas (figs.3–4). They are discussed in the main entry for this painting.

Fig.3

Inscription on the back of the painting: ‘Sir Neil Oneil Baronet of Killilaugh’

Fig.4

Signature and inscription on the back of the painting; ‘Jo.s Mich: Wright Lond iis Pictor Regius pinxit. 1680.’

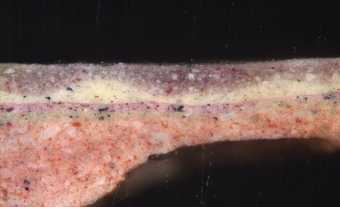

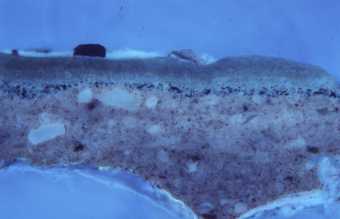

The ground is a vivid opaque salmon pink colour, composed of lead white, vermilion, red ochre, black, a few glassy particles bound together in oil (figs.5–6).2 The presence of a very thin, fluorescent line through the middle of the ground (fig.6), which shows the ground viewed in ultraviolet light, may mean that the salmon pink ground mixture was applied in two coats. There is no priming layer.

Fig.5

Cross-section through the sitter’s left stocking, photographed at x250 magnification. From the bottom: salmon pink ground; thin, dark grey dead colouring; red paint of stocking; thin surface crust of black discolouration; varnish

Fig.6

Cross-section through the sitter’s left stocking, photographed at x250 magnification in ultraviolet light with a blue filter. From the bottom: salmon pink ground; thin, dark grey dead colouring; red paint of stocking; thin surface crust of black discolouration; varnish

Examination with high magnification and with infrared reflectography revealed no trace of underdrawing (figs.7–9).

This is not surprising given the presence of opaque dead colouring apparently throughout the composition.3 As is evident with close examination and in cross-section samples, most of the figure and the background are underpainted in grey tones (figs.10–19).

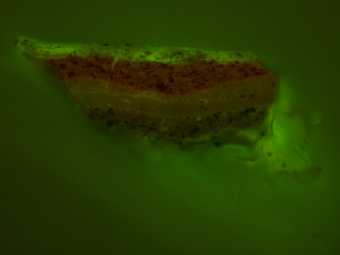

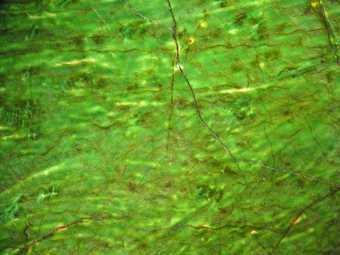

For areas destined to be glazed with translucent paint, the green cloak for example, the artist laid in underpainting in dark grey for the folds and opaque white for the highlights (figs.20–21).

Fig.20

Cross-section through the translucent green glaze paint on a highlight of the green cloak, photographed at x320 magnification. From the bottom: (ground and probably dark dead colouring are missing from sample); white underpaint; thick green glaze paint

Fig.21

Cross-section through translucent green glaze paint on a highlight of the green cloak, photographed at x320 magnification in ultraviolet light. From the bottom: (ground and probably dark dead colouring are missing from sample); white underpaint; thick green glaze paint. Slight fading of the colour is apparent in the upper section of this layer

For the final painting Wright worked mainly wet-in-wet, for example in the foliage, the flesh tones, the sky, the dog and the red shield (figs.11–14 and 22–24). Elsewhere, however, he used a layered technique, for example the slashed doublet (fig.10), the Japanese armour (figs.15–18) and the shoes.

Fig.22

Detail of the sitter’s right eye at x8 magnification, showing wet-in-wet brushwork

Fig.23

Detail of the sitter’s nose at x8 magnification, showing wet-in-wet brushwork

Fig.24

Detail of the sitter’s mouth at x8 magnification, showing wet-in-wet brushwork

The paint is mainly opaque but translucent glazing was added in parts to enrich the overall effect, for example blue and green glazes on the cloak (figs.25–26), red lake glazes on the shield and elsewhere.

Fig.25

Detail at x8 magnification of the blue glaze over white underpainting in the cloak

Fig.26

Detail at x8 magnification of the green glaze over white underpainting in the cloak

In some of the red glazes, for example the decoration on the shoes, chalk was added to the paint to thicken it (fig.27). Pigments used in the painting are as follows: the sky is made from lead white mixed with varying amounts of smalt and black; the sage green feather in the cap is made from a mixture of lead white, smalt, chalk, blue verditer, vermilion, lead tin yellow and bone black; the blue glaze on the cloak contains ultramarine, lead white, smalt, chalk and a trace of bone black; the green glaze on the cloak is made from a copper-based green plus smalt. Smalt, together with earth colours and black, is a major component in all the green tones in the foliage and the background.

Fig.27

Detail at x8 magnification of bodied red lake glazes on the shoe

The artist made a major alteration in the shield. Examination at high magnification reveals traces of an underlying painted scheme. Although this scheme is not discernible with X-radiography or infrared reflectography, it probably resembled the ‘antique’ battle scene depicted on the shield in another version of this painting at Dunrobin Castle, Scotland. Despite the assumption that Tate’s version is the earlier of the two (based on alterations to the figure made during painting), there appears to be no doubt that the alteration of the shield in Tate’s painting was made by Wright himself. The reason for this disparity between the two paintings cannot be discerned.

Fig.28

Detail at x8 magnification of discoloration in the vermilion paint of the red cap

The stockings and the red cap have undergone significant change since leaving the artist’s studio. On the cap and on the highlit side of each leg the bright red vermilion paint has developed a black or grey crust on its surface, a known phenomenon in older paintings that is not yet fully understood (fig.28). Attempts were made in the past to mask the discolouration on the legs with retouching; this work became visible as the retouching darkened with age. This feature is illustrated in the infrared refectogram (fig.7), which like most of the photography and all of the analysis of the painting, was done before the painting was cleaned and restored in 2012. It is interesting that the shadowed sides of the legs appear to have undergone no change at all; unlike the highlit sides, which were painted in pure vermilion, the shadowed sides contain vermilion mixed with red lake, smalt, chalk and black. In the restoration of 2012 the discoloured areas on the legs were retouched with easily removable paint to give an impression of their original appearance. Other changes in the painting are the cracking and darkening of most of the landscape, due mainly to the presence of smalt in the paint.

May 2012