Fig.1

Sir Peter Lely 1618‒1680

Susanna and the Elders

c.1650–5

Oil paint on canvas

1270 x 1492 mm

T00452

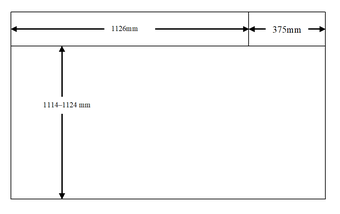

This painting is in oil paint on canvas measuring 1270 x 1492 mm (fig.1). The support is composed of three pieces of plain woven, linen canvas, stitched together at seams, as shown in the diagram below and in the X-radiograph (fig.2).

Fig.2

X-radiograph of Susanna and the Elders c.1650–5

The main piece of canvas has 15 vertical x 13.6 horizontal threads per square centimetre; the additional strips have 13.7 horizontal x 15 vertical. In addition to their similar appearance in the x-radiograph, this indicates that the strips were cut from the width of the same roll of canvas as the main piece.1 Cusping of the canvas weave on all sides of the painting gives us the information that the painting has not been cut down in size significantly; absence of cusping on the main piece at the seam indicates that the canvas was never attached to a strainer at this point, and that the composite support existed from the inception of this painting.2 Linear cracks in the painting, made by the bars of the original stretcher, show that those bars were 32 mm (1 ½ inches) wide. A horizontal bar mark is exactly equidistant between the top and bottom edges of the composition, another confirmation that the painting’s dimensions are as originally. A central vertical bar mark passes through Susanna’s left arm.

The ground is opaque mid-grey in colour (figs.3–4). It was applied smoothly and is composed of lead white mixed with charcoal black and a range of earth colours, all bound together in oil.3 There is no priming. No underdrawing is detectable with any method of examination, a familiar feature of Lely’s work in this study.

Fig.3

Cross-section through Susanna’s white drapery, photographed at x320 magnification. From the bottom: grey ground; flesh paint; white paint of robe; varnish and dirt

Fig.4

Cross-section through Susanna’s white drapery, photographed at x320 magnification in ultraviolet light. From the bottom: grey ground; flesh paint; white paint of robe; varnish and dirt

The figures were laid in broadly with reddish brown paint. This colour was often left to show as the shadowed outlines of the flesh tones, and in this painting we can see this technique in the hands and faces (figs.5–8). The artist went on to strengthen some of these areas with similar paint at a later stage of painting.

The painting was done mainly in one layer, with colours mixed up on the palette and worked into one another wet-in-wet on the prepared canvas (figs.9–14). Some areas, for example the shadows of drapery, were glazed when dry with semi-translucent paint. The dark purplish tones were made from mixtures of black, Cologne earth, various reddish and brownish earth colours and umbers, lead white, smalt, red lake and gypsum. The greens of the foliage were mixed from green earth, smalt, earth colours, black and lead tin yellow. The Elder’s red gown was made from vermilion mixed with lead white, gypsum, chalk and glassy particles. The dark greenish grey background was mixed from Cologne earth; smalt and black; while the flesh tones are based on lead white with vermilion and black. Analysis of the binding medium revealed that the oil in most of the composition was partially heat-bodied linseed oil, with an addition of pine resin in some of the dark background areas and in the red robe. The oil for Susanna’s white shift was fully heat-bodied.4

During treatment at Tate in 2005, a thick coating of aged, natural resin varnish was removed, along with non-original restoration that covered severe, old abrasion of the original. The original paint in many of the dark areas has a worn appearance, especially so in a horizontal band across the top of the painting, starting at roughly the mid-point between the seam and the top edge. The existing glue composition lining and its contemporary wooden stretcher were retained.

The Tate painting was compared with the version in Birmingham City Art Gallery (Acc.No.1948P23).5 It seems likely that the Birmingham painting is the earlier of the two; in Tate’s picture a pentimento of a hand is visible beneath the beard of the Elder in full profile, matching the visible hand in the Birmingham version.

January 2011