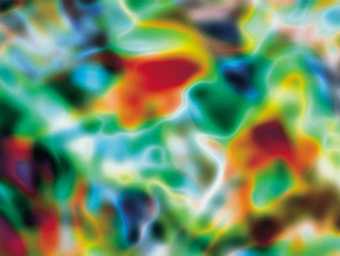

Thomas Ruff

Substratum 1II 2001

inkjet on paper

Courtesy the artist & the Staatliche Kunsthalle Baden-Baden © Thomas Ruff

If, in our ‘virtual’ age, it can still be said that photographs furnish evidence, then Thomas Ruff’s body of work is testimony to the sheer wealth of practices, objects and forms available to photographers today. Ruff has been testing the limits of his medium for more than two decades, completing a dozen series of photographs that range from seemingly banal images of streets and buildings to computer-generated prints of sensuous psychedelic colour fields.

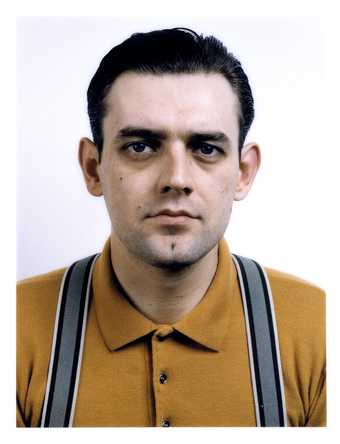

Thomas Ruff

Portrait 1983

C-print

Courtesy the artist & the Staatliche Kunsthalle Baden-Baden © the artist

While he is perhaps best known for his revival of the portrait during the early 1980s, and then for blowing the prints up to a monumental scale, Ruff has never stuck to one genre or method. He has investigated a composite picture-making apparatus – the Minolta montage machine – for Other Portraits; an infrared lens for Nights; hand-tinting; stereo photographs; digital retouching and photomontage. He has even borrowed images, as in Stars, where he reprinted details of photos of night skies shot by the European Southern Observatory that, for an avid star-gazer like me, are almost scandalous in their beauty. Further appropriations occur in his Newspaper Photographs series, and more recently his Nudes, pornographic pictures downloaded from the internet and digitally modified.

Thomas Ruff

03h 00m / -35 1989

C-print

Courtesy the artist & the Staatliche Kunsthalle Baden-Baden © the artist

Thomas Ruff

House Number 7 1983

C-print

Courtesy the artist & the Staatliche Kunsthalle Baden-Baden © the artist

There is no obvious chronological progression to Ruff’s work, nor is there a clear hierarchy of pictorial discoveries: sophisticated technologies, as they become available, rival those ready to hand since the 19th century. Threedimensional illusion co-exists alongside categorical flatness; the graphic sexual image contaminates the neutral portrait via eerie, vitriolic nightscapes. The more one looks, the more one retains in one’s visual memory, the more each part seems to be related to an everchanging, still elusive whole.

Ruff began studying photography in the late 1970s under Bernd Becher at the Kunstakademie Dsseldorf. Indeed, the impact of Bernd and Hilla Becher’s black-and-white typologies of industrial structures and landscapes on a whole generation of German photographers cannot be overestimated. The Bechers encouraged budding photographers to emulate their factually exact, tonally uniform approach to image-making.

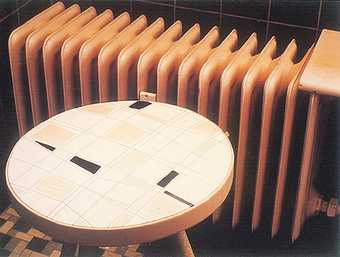

Thomas Ruff

Interior 1a 1979

C-print

Courtesy the artist & the Staatliche Kunsthalle Baden-Baden © the artist

While profiting from their lessons, Ruff quickly distinguished himself from his teachers by delving into colour, a move that radically challenged the presumed authenticity of the blackand-white image on which traditions of documentary photography have long been based. Early works bear the mark of his training and of his maverick attitude. His photographs of the interiors of homes belonging to friends and family, made between 1979 and 1983, are as rigorously composed as any Becher water tower: the cropping of each vertical image draws attention to the (often horizontal) details of geometric pattern, texture, and the dull glow of natural light shining off polished wood and immaculate tiles.

Thomas Ruff

Interior 1E 1983

C-print

Courtesy the artist & the Staatliche Kunsthalle Baden-Baden © the artist

These middle-class interiors are visual cul-de-sacs: each mirror reflects a wall, every open door leads to another that is closed, corners block our gaze. Their impenetrable aspect is amplified by the physical absence of the inhabitants; human likeness is limited solely to the occasional portrait photograph, which, in retrospect, seem to be prophetic in character. Here, Ruff’s distanced objectivity, inherited from the Bechers, holds in ways it cannot hold in later images; perceptually, at least, we can go no further than the photographer allows us to see.

Paradoxically, though, such static compositions have the effect of throwing the viewer back on to her or his own identificatory devices, of freeing up the imagination. For, despite the critical consensus that Ruff wants to make no judgement about what he sees, nothing in those pictures prevents me from projecting into them: from marvelling over the neatly turned-down linens, to recalling that my Polish grandmother hung crucifixes over the beds in her apartment too, or that we had similar striped soap on our sink.

This capacity to capture one time and place and transfer it into another is one of photography’s most enduring qualities. Yet let there be no doubt: Thomas Ruff is hardly interested in whatever personal reminiscences I may glean from his images; he simply accepts them as one of the inevitable burdens of his chosen medium. He has no desire to get at some deeper meaning or the inner essence of what he photographs, yet he recognises that aesthetic judgements or socio-cultural content are inscribed there. His published interviews indicate that he is a photographer who knows precisely where his interests lie – in the image produced and its means of production – and precisely where his control leaves off – at the level of interpretation. As such, his oft-cited claim that ‘photography can only reproduce the surface of things’ must be tempered with his assertion that ‘what people see, eventually, is only what’s already inside them.’

Ruff multiplies our visual experiences by extending his frames of reference beyond the surface of the photograph, beyond the primary level of what is depicted, particularly towards other kinds of pictures. This referential complexity is evident in his portraits and his built and natural landscapes, which allude to such mass-produced images as passport photographs and postcards. He interferes with the stark neutrality of certain of his architectural photos with more painterly versions of the same building, while his use of blurring effects, whether produced with the lens or computer manipulation, triggers an association with the photographically realist paintings of artists such as Gerhard Richter.

Thomas Ruff

Nudes dyk03 1999

C-print

Courtesy the artist & the Staatliche Kunsthalle Baden-Baden © the artist

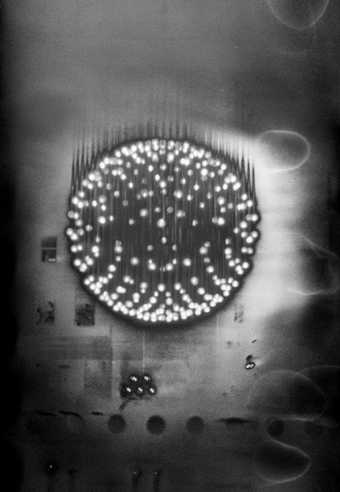

Photography’s long-standing and unresolved relationship with painting is thrown into further relief in Ruff’s more recent work, created entirely through digital means. In the Nudes, Ruff’s manipulation of the image impedes our visual access to the depicted scenes, and tones down their aggressive sexual nature. The abstract colour surfaces of the Substratum photographs, composed out of the vast visual culture of the internet, go so far as to liberate photographic representation from its dependence on the real. At the same time, no matter how much one might want to see painting or digital virtuosity here, there seems to be no getting around the matter of the photograph. After all, a substratum is what facilitates the adhesion of the light-sensitive emulsion in the making of one. It is, in a sense, the very foundation of the photographic image.

That being the case, does Ruff’s unwavering exploration of the photograph’s surface finally reveal what lies behind it? Or are we really just dealing with appearances? Susan Sontag wrote that the inherently deceptive nature of photography can only provide, ‘a semblance of knowledge, a semblance of wisdom; as the act of taking pictures is a semblance of appropriation, a semblance of rape’ (On Photography, 1977). Walter Benjamin (On Semblance, 1919–20) drew distinction between ‘the semblance behind which something is concealed (for example, the seductive: the Lady World of medieval legend whose back is devoured by worms, while from the front she looks beautiful) and the semblance behind which nothing is concealed (a Fata Morgana or chimera).’

In the end, perhaps it is his ability to maintain this tension between what we see and what we think we see, between what is there and what seems to be there, that holds us captive to Thomas Ruff’s art of making pictures.