‘A sincere academic modern’: Clement Greenberg on Henry Moore

Courtney J. Martin

In 1947 Clement Greenberg wrote a scathing review of Moore’s retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York and in the following decades he continued to present the sculptor as a minor artist of limited interest. This essay explores the reasons why Greenberg remained so dismissive of the British artist.

Painting continues to hold the field, by virtue of its greater breadth of statement as well as by its greater energy. And sculpture has become a place where, as hopes have turned into illusions, inflated reputations and inflated renaissances flourish.1

Clement Greenberg 1956

Clement Greenberg 1956

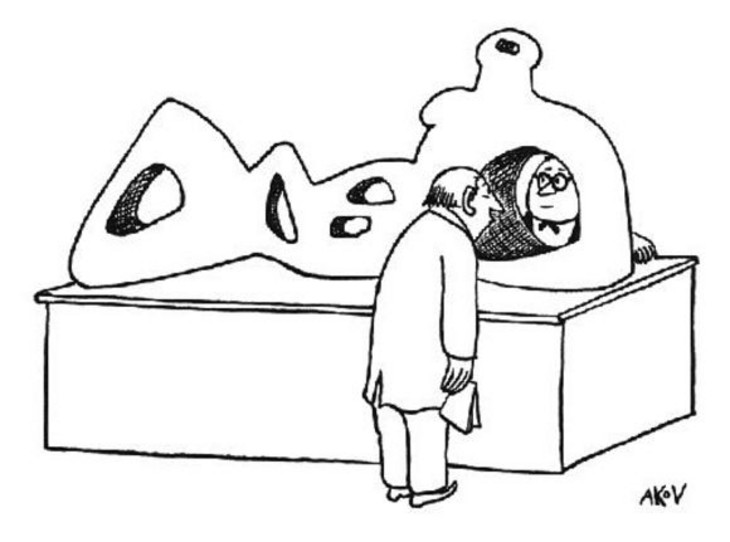

From December 1946 to March 1947 the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York held a major retrospective of the work of Henry Moore, which then travelled to Chicago and San Francisco. The exhibition contained some of the British artist’s most important works, including some of his already well-known wartime Shelter drawings of people taking refuge from the Blitz in the London Underground. The highly anticipated show proved a critical success, and Moore and his work featured prominently in the nation’s newspapers, magazines and television. So much so that his sculptures with ‘holes’ became a popular visual cliché: a contemporaneous New Yorker cartoon (fig.1) showed two men looking at each other – one joyless and the other a little anxious – through a ‘hole’ in a Moore-like reclining figure.

If those two figures bore more than a passing resemblance to the art critic Clement Greenberg, engaged in close looking and armed with a notebook, and Alfred Barr, MoMA’s bespectacled director, it may have been an insider’s reference to the critic’s appraisal of the Modern’s Moore exhibition. On 8 February 1947 Greenberg (1909–1994) published in the Nation a scathing review of the exhibition that set the tone for the way in which the American critic would refer to the British sculptor in the years to come. Although short – eight succinct paragraphs in length, half shared with comments on another sculptor – the review was the single, anomalous crease in the otherwise smoothly orchestrated and well received presentation of Moore in New York. Greenberg presented Moore as both a symbol of the inadequacy of post-war sculpture in relation to contemporary painting and as an example of ‘Englishness’ – in Greenberg’s usage, a somewhat vague term intended to imply an incapacity to create ‘truly original modern sculpture’.2

Greenberg returned to Moore’s sculpture nearly a dozen times between 1947 and 1968, the last year in which he mentioned the English sculptor in his criticism. Throughout Moore remained a figure to be surpassed and overthrown by younger artists or, in Greenberg’s words of 1968, ‘Abraham’ to the ‘Moses’ of the younger British sculptor Anthony Caro (1924–2013), who had once been a trusted assistant of Moore’s. According to Greenberg, the work of Caro, together with the American sculptor David Smith (1906–1965), offered a path that was equal in aesthetic potential to that of the painters that he championed, such as Helen Frankenthaler, Kenneth Noland and Jackson Pollock.3

This essay explores how over two decades Greenberg’s writings constructed an image of Moore as a traditional and limited artist (‘a sincere academic modern’4 was one of Greenberg’s coded phrases), a foil to what he later proclaimed to be the new sculptural avant-garde led by Smith and Caro. Greenberg’s devotion to Smith and promotion of Caro have been seen as evidence of the critic’s willingness to depart from his earlier beliefs about the supremacy of abstract painting over all other forms of art. However, Greenberg’s dismissal of Moore was bound up in a relative disinterest in sculpture in the early part of his career and, for a period, near obsession with proving its secondary status to painting.5

Moore in New York

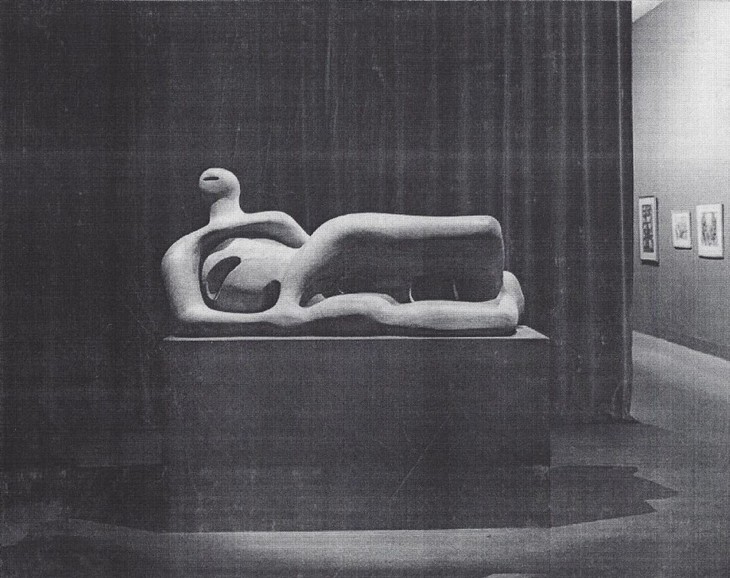

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Recumbent Figure 1938

Green Hornton stone

object: 889 x 1327 x 737 mm, 520 kg

Tate N05387

Presented by the Contemporary Art Society 1939

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Henry Moore OM, CH

Recumbent Figure 1938

Tate N05387

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The pavilion was planned by representatives of the British Council working with a team from MoMA that may have included curator James Johnson Sweeney.9 In a preview of the fair’s American art programme, published in March 1939, Sweeney commented on what he saw as a lack of adventurousness in the fair’s approach to art: ‘Perhaps the first step toward ‘Building a Better World of Tomorrow’ with the ‘Tools of Today in the field of Art’ would have been to attack the museum approach without any reserve and to emphasize the need to look to the everyday world about us for the vital formal and emotional experiences from which the art of tomorrow will be built.’10 While he did not provide specific examples of the artists that would have fulfilled his vision for the exhibition, Moore’s stone and wood sculptures in the British pavilion would perhaps have exemplified for Sweeney the ‘everyday world’ aesthetic that could spark ‘emotional experiences’.

Sweeney was an avid sculpture collector and in the early 1940s he acquired two of Moore’s watercolours, Mother and Child 1940 and Reclining Figures Against A Bank 1942 (sculptures by Moore were hard to come by during the war years because of the difficulties of transporting works across the sea). Both works were illustrated in the 1944 volume, Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings, which was introduced by the English critic Herbert Read and published by Moore’s American dealer Curt Valentin.11 Director of the museum’s department of painting and sculpture from 1945, Sweeney proposed a major retrospective of Moore’s work for the autumn of 1946. Although he was no longer in post when the exhibition opened, he selected the show and wrote the catalogue’s only essay. 12 In a letter to a colleague, his successor Monroe Wheeler noted that, ‘In selecting the Henry Moore exhibition, Jim Sweeney worked for the most part from the Herbert Read book’, as the best available source of images and information on the artist.13 Echoing Read’s text, Sweeney eulogised Moore in his catalogue essay. ‘Moore is still the one important figure in contemporary English sculpture’, he claimed, and ‘has taken his place in the international forefront as well.’ ‘As an artist Moore has the courage, the craftsmanship and talent that match his personal sympathy, humility and integrity. And in spite of the maturity and individuality of his early production, Moore has grown in statue as a creative artist with every completed major work’.14 Heavily dependent upon the artist’s own concepts (and thus, by extension, those of the artist’s chief champion, Herbert Read), Sweeney’s essay was laced with numerous passages from Moore’s published statements. Describing the sculptor’s methods as neither ‘arbitrary’ nor ‘stiffly intellectual’, Sweeney cited Moore’s own clear and simple formulation of how his ideas and imagination came together in his works:

Sweeney was an avid sculpture collector and in the early 1940s he acquired two of Moore’s watercolours, Mother and Child 1940 and Reclining Figures Against A Bank 1942 (sculptures by Moore were hard to come by during the war years because of the difficulties of transporting works across the sea). Both works were illustrated in the 1944 volume, Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings, which was introduced by the English critic Herbert Read and published by Moore’s American dealer Curt Valentin.11 Director of the museum’s department of painting and sculpture from 1945, Sweeney proposed a major retrospective of Moore’s work for the autumn of 1946. Although he was no longer in post when the exhibition opened, he selected the show and wrote the catalogue’s only essay. 12 In a letter to a colleague, his successor Monroe Wheeler noted that, ‘In selecting the Henry Moore exhibition, Jim Sweeney worked for the most part from the Herbert Read book’, as the best available source of images and information on the artist.13 Echoing Read’s text, Sweeney eulogised Moore in his catalogue essay. ‘Moore is still the one important figure in contemporary English sculpture’, he claimed, and ‘has taken his place in the international forefront as well.’ ‘As an artist Moore has the courage, the craftsmanship and talent that match his personal sympathy, humility and integrity. And in spite of the maturity and individuality of his early production, Moore has grown in statue as a creative artist with every completed major work’.14 Heavily dependent upon the artist’s own concepts (and thus, by extension, those of the artist’s chief champion, Herbert Read), Sweeney’s essay was laced with numerous passages from Moore’s published statements. Describing the sculptor’s methods as neither ‘arbitrary’ nor ‘stiffly intellectual’, Sweeney cited Moore’s own clear and simple formulation of how his ideas and imagination came together in his works:

sometimes I start with a set subject; or to solve, in a block of stone of known dimensions, a sculptural problem I’ve given myself, and then consciously attempt to build an ordered relationship of forms which shall express my idea. But if the work is to be more than just a sculptural exercise, unexplainable jumps in the process of thought occur; and the imagination plays its part.15

Passages like these shaped an image of an artist who was as skilled as he was intuitive, and supported the already widespread perception that Moore’s work was very much an expression of Moore the man. Such statements were also in tune with MoMA’s presentation of modernism after the war, in which a previous emphasis on modernism’s disruptive aesthetic and political radicalism was replaced by a new concern to highlight thoughtfulness and contemplation in the making of art.

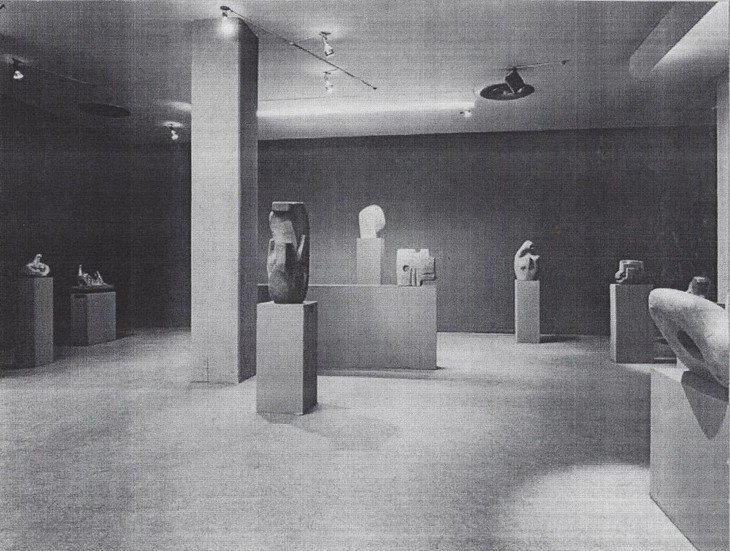

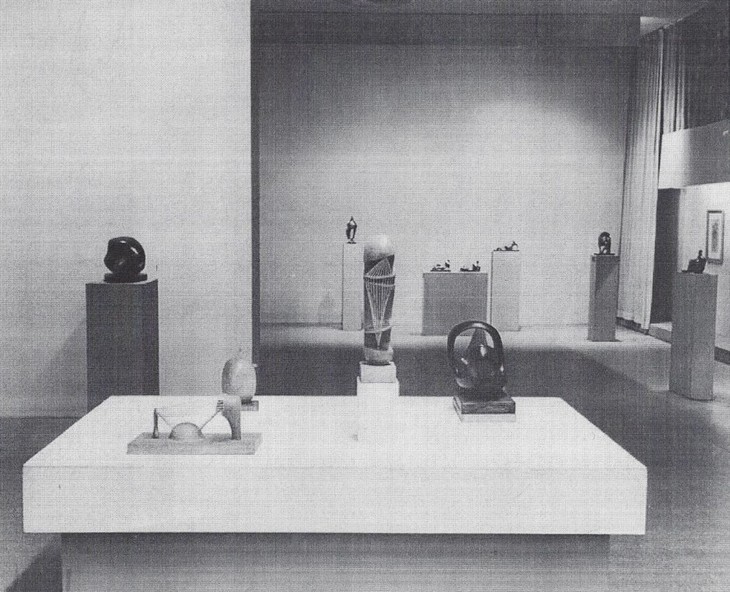

For the opening of the exhibition MoMA invited Moore to New York for what was his first trip to the United States. The museum eagerly promoted the exhibition as the largest show of the British artist’s work ‘ever held in any country’ and the press office even pushed for a possible Paramount newsreel.16 The plan fell through because the museum would not allow Paramount full control over the project, but Falcon Films produced a film of the private view that was directed, scripted and narrated by Sweeney and in which Moore made an appearance.

View of the exhibition Henry Moore at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1946–7

Fig.3

View of the exhibition Henry Moore at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1946–7

View of the exhibition Henry Moore at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1946–7

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

View of the exhibition Henry Moore at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1946–7

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

View of Moore's Four-Piece Composition (Reclining Figure) 1934 in the exhibition Henry Moore at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1946–7

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.5

View of Moore's Four-Piece Composition (Reclining Figure) 1934 in the exhibition Henry Moore at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1946–7

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Greenberg’s review

Press response to the exhibition was overwhelmingly positive, with glowing articles in the New York Times and New York Herald Tribune as well as in popular magazines. In Vogue Moore was profiled as intriguingly ‘controversial’ in the manner of a young Picasso.18 Most reviews indicated that the exhibition revealed Moore to have ‘an original mind’19 and that Sweeney had shown ‘balanced judgment’ in his selection.20 Writing for the New York Times, Eric Newton, the art critic for the Sunday Times in London, concluded, as did many, that the show was ‘extraordinarily satisfying’.21 In his criticism of Moore’s works, Greenberg was thus very much a lone voice.

Greenberg had come to art criticism relatively late in life, having previously worked as a salesman, translator, civil servant and literary critic. The profession suited him: he enjoyed travelling, was multi-lingual, and the role of art critic allowed him, a son of middle class Jewish immigrants, entrée to the patrician heights of American culture already comfortably inhabited by the likes of Barr and Sweeney. When he moved from literary to art criticism in the late 1930s, Greenberg sought above all else evidence of originality in art. His early essays, notably ‘Avant-Garde and Kitsch’ (1939) and ‘Towards a Newer Laocoon’ (1940), purported to consider both painting and sculpture but nonetheless showed his greater interest in the former. Soon he made clear his preference for the new types of abstract painting being made in New York. Writing in 1943 about Jackson Pollock’s solo exhibition at the Art of This Century gallery, Greenberg described his ‘surprise and fulfilment’ at seeing Pollock’s ‘not so abstract abstractions’.22 Perhaps what appealed most to him about the new abstract painting was its position outside of the polite society that dominated New York’s art world of the 1940s. Artists such as Pollock were not only little known but also inhabited relatively uncharted realms of the city where they painted wildly, listened to Jazz music, cohabited without the sanction of marriage, drank and argued, and, generally, lived a life that Greenberg happily mythologised for his growing readership in the Partisan Review, Nation and New York Times.

‘Americaness’ – an idea interpreted variously by Greenberg to denote a certain roughness and originality – was an aspect of the new art that Greenberg vaunted and often used to contrast the work of his artist friends in downtown New York with that of English and European artists. In his 1943 review he linked Pollock’s painting to a national literary tradition evinced by such writers as Nathaniel Hawthorne, Herman Melville and Edgar Allen Poe.23 In an article published in the Nation on 22 February 1947 (that is, immediately after his review of the Moore exhibition), he contrasted American and French art, conceding that the former might lack ‘poise’ but asserting that it evinced ‘more originality and more honesty.’24 He found English culture lacking in vigour: quite simply, ‘Anglo-Saxon painting was usually not ambitious enough’, and its sculpture was even less so.25 Greenberg’s relative lack of enthusiasm in this period for sculpture and for English art in particular thus predisposed him to dislike Moore’s retrospective.

Greenberg reviewed the exhibition together with a show of the work of the French-American sculptor Gaston Lachaise at the Knoedler Gallery for the Nation, a weekly serial for which he had written since 1942, in early February 1947. A week earlier Greenberg had provided an elegant assessment of exhibitions by Jean Dubuffet and Pollock, in which he dubbed the latter ‘the most important so far of the younger generation of American painters’26 and found him, predictably, to be more original than the French artist. A similarly competitive tone pervaded his review of the Moore and Lachaise exhibitions. His first full paragraph ended by saying that, ‘Moore, setting his terms so much higher and wider seems to fill them completely in an oeuvre already resonant with almost everything that twentieth-century sculpture, painting, and construction have had to say. And yet, still, Lachaise is the better artist.’27 He went on to dismiss Moore’s work as too easy: ‘The very real fact that it meets our taste so ideally banishes all real difficulty or surprise from Moore’s art. It is, alas, this subservience to taste that condemns him, along with Calder, Stuart Davis, Graham Sutherland, and sundry Anglo-Saxons, to the category [‘easy’ art] – not as populous as might be thought, but very popular just now’.28

As a literary critic Greenberg had admired English poetry in the 1940s for its ability to combine ‘rich tradition’ with an ‘avant-garde morale’, but he could not bring himself to admire Moore’s recourse to past examples of world art in the name of modernism.29 Moore’s allusions to archaic and primitive art were, he felt, backward looking and derivative, ‘a helpless fingering of archaeological reminiscences’.30 By contrast, Greenberg vaunted the work of the Romanian Constantin Brancusi as an example of someone who had produced ‘truly original modern sculpture’, strangely ignoring the latter’s debts to folk and African art. Finally, Greenberg found Moore’s public persona and the quasi-philosophical aura engendered by the mantra ‘truth to materials’ grating. Moore could summon ‘no amount of facility or awareness’ to ‘make good the shortcomings of what Croce calls personality’.31 In comparison with the glamourous squalor of the lives of the downtown abstract painters, Moore – admired in the American press for his English charm and for his humble origins – was a square.

In condemning Moore, Greenberg was also of course implicitly criticising MoMA for its selection of a British artist for a major retrospective and its motives for doing so. He was irritated by the museum’s pro-European agenda and apparent disregard for the great art being produced on its own doorstep. He also suspected that the museum was insufficiently independent of the market in its judgments. In a 1943 review of the museum’s recent purchases, for example, he cuttingly referred to the ‘extreme sensitivity of the museum to trade winds on Fifty-seventh Street’.32 In the following year he reported, and thus publicised, criticism of the museum by the Federation of Modern Painters and Sculptors, a group that included many of his closest artist friends, and let his own thoughts about MoMA be known: ‘The function of a museum of modern art’, he averred, ‘is to discriminate and support those tendencies in art which are specifically and validly modern, regardless of general appeal or vogue.’33 Writing for the British literary magazine Horizon in October 1947 he criticised the museum, the ‘principal impresario of modern art’, for its failure to buck the market and support the young and still under-recognised American abstract painters he believed in: ‘Pusillanimity makes the museum follow the lead of the most powerful art dealers; only once in a while will it show or buy an artist lacking 57th Street’s imprimatur.’34

Conceivably, Greenberg would have condemned any artist exhibited at MoMA who was not of the emerging school of New York-based abstract expressionism or who was not of the first generation of modernism’s heroes. Moore did not have a particularly distinguished artistic pedigree (unlike that of Matisse or Picasso, for example) nor was he truly representative of the new direction of contemporary art, much as the rest of the art world, Greenberg acidly claimed, was deceiving itself that he was (his sculpture ‘answers too perfectly the current notion of how modern sophisticated and inventive sculpture should look, without at the same time disappointing the popular demand for the heroic’).35 Moore’s work was not good enough because it was not abstract enough and because his vision was one constrained by timidity (‘Moore fails because his feeling is incomplete, or because he has not pressed himself, or because he has not pressed himself to complete it’).36 He may have been part of the modernist canon but only as ‘a sincere academic modern’, not as a pioneering or revolutionary figure, although Greenberg conceded that Moore’s work before 1935 was of interest and even highlighted a few later works in the exhibition that were of merit:

Moore possesses no mean talent, and some of his later work, from the two reclining figures of 1938 (one in stone and one in lead) and The Helmet of 1940 (in lead) to the two bronze family groups of 1945 and 1946, will surely outlast the transient ardors of that informed contemporary taste upon which Moore’s art is now making what I feel is an exaggerated impression.37

Later criticism

Greenberg continued to criticise Moore’s work when the opportunity arose. In April 1947 Moore featured in a list of modern sculptors that his American protégé David Smith was greater than or equal to in skill and innovativeness.38 In October Greenberg found Moore’s work in a group show of British art, held in Provincetown, to be ‘tasteful and monotonous as ever’.39 Two years later Moore surfaced in a review of an exhibition by the British painter Ben Nicholson: ‘this painter tends to academicize his art somewhat by confining it within a style established in its essentials by other artists, and by subjecting it to the primacy of taste – taste over strength, taste over boldness, richness, originality. Here he is not unlike other contemporary British artists and, especially, the sculptor Henry Moore.’40 The reference to academicism recalled Greenberg’s 1947 description of Moore as a ‘sincere academic modern’, and he likewise condemned Nicholson for similar faults: the painter played ‘some real part’ in contemporary art but suffered from Moore’s weakness of ‘inappropriate pretentiousness’.41

After the 1947 review Moore made just eleven minor appearances in Greenberg’s criticism. He was cited as an example of ‘modernistic trickiness’42 and an unworthy point of comparison (‘Moore hardly deserves to be mentioned in the same breath’).43 These disparagements made Greenberg’s stance known without requiring him to substantiate his views through argument. In a sense, his dismissal of Moore was thus similar to his treatment of the writings of the English critic and champion of Moore, Herbert Read. In 1947 Greenberg wrote in trenchant terms, ‘I believe that the evidence upon which Herbert Read rests his suggestion that abstract and naturalistic art are compatible in the same age and even in the same person is illusory,’44 but thereafter was content briefly to dismiss Read as an ‘incompetent critic’ without further ado.45

In the 1950s Greenberg refined his position on sculpture. He now called for a new sculpture that developed aspects of cubism, renounced illusion and explicit subject matter and was generally constructed from industrial materials. ‘The new construction-sculpture’, he wrote in 1958,

points back, almost insistently, to its origins in Cubist painting: by its linearism and linear intricacies, by its openness and transparency and weightlessness, and by its preoccupation with surface as skin alone, which it expresses in blade-or sheet-like forms. Space is there to be shaped, divided, enclosed, but not to be filled or sealed in. The new sculpture tends to abandon stone, bronze and clay for industrial materials like iron, steel, alloys, glass, plastics, celluloid, etc.46

This definition excluded most of Moore’s works, based as they were on traditional materials and an exploration of solids rather than transparency or weightlessness. But it found exponents in David Smith in America and – perhaps surprisingly given Greenberg’s antipathy to English art – in Anthony Caro. Greenberg met Caro, then aged thirty-five, in 1959 and soon introduced him to Smith and other American artists. In his first review of Caro, Greenberg likened him to Smith as the ‘only new sculptor whose sustained quality can bear comparison’ with the older American sculptor.47 In the Englishman Greenberg found another sculptor willing to move into full abstraction using ‘vectors, lines of force and direction’.48 But when promoting Caro’s work, he was notably keen, even desperate, to deny Moore any significant role in the former’s artistic development. In an interview of 1968 Greenberg claimed: ‘Caro is the Moses of English sculpture – not Moore; Moore’s the Abraham maybe, a father, a generator, but not a leader, not even an example’.49 However, he now thought that Moore, albeit a ‘minor artist’, produced his ‘best work’ up to 1940, rather than 1935 as he had claimed in his 1947 review, and was willing to concede that Moore had played a role in helping to create a ‘milieu for sculpture’ that had nurtured the talents of Caro. He confessed that he liked Moore ‘most when he’s most modest’ but still complained of what he saw as ‘English neatness, English patness’.50 Echoes of Greenberg’s ideas were found in the writings of English critic Lawrence Alloway, who in the late 1950s looked to American art for innovation and inspiration. In 1958 Alloway described Moore as ‘somebody to react against’51 because he ‘is linked with the idea that three-dimensional sculpture must look good from all around and this has popularly become an absolute requirement of ‘true’ sculpture. In fact, the front-back-and sides view of sculpture is only one of several possible approaches.’52 But Alloway, too, was pretty much a lone negative voice amidst the tide of general approval of Moore’s works in Britain in the 1950s and early 1960s.

Within America, and beyond, Greenberg was an influential exponent of modernist aesthetics and a tastemaker at a time when New York was seen as the world capital of art. His hostility towards Moore might have been expected to have dented the Englishman’s reputation, at least in New York circles, but there is no sign that it did. Greenberg never met Moore, and there is no evidence that the American critic’s barbs particularly concerned Moore or affected the legions of his American patrons. It is possible that Greenberg’s dismissal of Moore was part of the context in which forty-one younger artists, including Caro, wrote a letter to the Times in 1967 protesting at the idea that Moore should have a new gallery permanently devoted to his work in the Tate Gallery,53 but generally support for Moore came from quarters that were unswayed by Greenberg’s criticism. The wealthy and the influential continued to collect and commission works from Moore, and his sculpture continued to be viewed as expressive of an aesthetic that art experts and ordinary people found both challenging and moving. Greenberg’s 1947 comment that Moore’s sculptures fulfilled current notions of ‘how modern sophisticated and inventive sculpture should look, without at the same time disappointing the popular demand for the heroic’ was perhaps not far from the mark in explaining Moore’s popularity in the post-war years. However, the nearly dozen references to Moore, albeit generally brief and dismissive, in Greenberg’s critical writings show that, whether he liked the Englishman’s work or not, Moore remained important to any discussion of sculpture, British art or modern art in the post-war period and could not be ignored.

Notes

Clement Greenberg, ‘David Smith,’ Art in America, Winter 1956–7, reprinted in Clement Greenberg: The Collected Essays and Criticism. Volume 3: Affirmations and Refusals 1950–1956, edited by John O’Brian, Chicago 1993, p.276.

Clement Greenberg, ‘Review of Exhibitions of Gaston Lachaise and Henry Moore’, Nation, 8 February 1947, reprinted in Clement Greenberg: The Collected Essays and Criticism. Volume 2: Arrogant Purpose, 1945–1949, edited by John O’Brian, Chicago 1993, p.127.

‘Interview Conducted by Edward Lucie-Smith’, Studio International, January 1968, reprinted in Clement Greenberg: The Collected Essays and Criticism. Volume 4: Modernism with a Vengeance 1957–1969, edited by John O’Brian, Chicago 1993, p.279.

Greenberg, ‘Review of Exhibitions of Gaston Lachaise and Henry Moore’, reprinted in Clement Greenberg: The Collected Essays and Criticism. Volume 2: Arrogant Purpose, 1945–1949, 1993, p.127.

In ‘Towards A Newer Laocoon’ (1940) Greenberg wrote: ‘The history of avant-garde painting is that of a progressive surrender to the resistance of its medium; which resistance consists chiefly in the flat picture plane’s denial of efforts to “hole through” it for realistic perspectival space. In making this surrender, painting not only got rid of imitation – and with it, “literature” – but also of realistic imitation’s corollary confusion between painting and sculpture. (Sculpture, on its side, emphasizes the resistance of its material to the efforts of the artists to ply it into shapes uncharacteristic of stone, metal, wood, etc.)’ Reprinted in Clement Greenberg: The Collected Essays and Criticism. Volume 1: Perceptions and Judgments, 1939–1944, edited by John O’Brian, Chicago 1993, p.34.

Grover A. Whalen, ‘We Welcome the World’, The First Official Guide Book, New York World’s Fair 1939, New York 1939, p.5. The exhibition was described in 1940 by Frank Monaghan, historian and head of the Fair’s Research and Library Department, as ‘the last of the great comprehensive exhibitions’ (Frank Monaghan, ‘The Parade Of World’s Fairs’, New York History, vol.21, no.3, July 1940, p.260). For a discussion of the 1939 New York World’s Fair, see Robert W. Rydell (ed.), Designing Tomorrow: America’s World's Fairs of the 1930s, New Haven and London 2010.

Roland Marchand, ‘The Designers Go the Fair II: Norman Bel Geddes, The General Motor’s “Futurama”, and the Visit to the Factory Transformed’, Design Issues, no.8, Spring 1992, pp.23–40. For a discussion of the art included in the Fair, see Marco Duranti, ‘Utopia, Nostalgia and World War at the 1939–40 New York World’s Fair’, Journal of Contemporary History, vol.41, no.4, October 2006, pp.663–83.

The outbreak of war and the consequent impossibility of transporting non-essential goods across the Atlantic meant that it was difficult for further sculptures by Moore to seen in America in the early 1940s. However, he had a show of forty watercolours and drawings in Curt Valentin’s Buchholz Gallery in May 1943 and a drawings show at the Stendahl Gallery, Los Angeles, in September 1943. In the Nation Jean Connolly described the Bucholz show as ‘wonderful’ (22 May 1943, p.750).

For information relating to MoMA’s involvement with the British Council, see Nicholas J. Cull, ‘Overture to an Alliance: British Propaganda at the New York World’s Fair, 1939–1940’, Journal of British Studies, vol.36, no.3, July 1997, p.341 note 52.

James Johnson Sweeney, ‘Thoughts before the World’s Fair’, Parnassus, vol.11, no.3, March 1939, p.7.

Sweeney resigned from the museum in October 1946 and Monroe Wheeler assumed responsibility for the installation of the Moore exhibition at MoMA and for the tour of the show to other venues (James Johnson Sweeney, letter to Nelson Rockefeller, President of MoMA, 16 October 1964, Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York, Reg.339). Rene d’Harnoncourt, then in a provisional position at the museum, oversaw Wheeler’s work and liaised with Moore.

Monroe Wheeler, letter to Daniel Catton Rich, Art Institute of Chicago, 3 February 1947, Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York.

James Johnson Sweeney, Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Museum of Modern Art, New York 1946, p.88.

Sweeney 1946, p.31. The passage first appeared in ‘The Sculptor Speaks’ in the Listener on 18 August 1937.

‘The Talk of the Town’, New Yorker, 21 December 1946, p.18. The exact number of objects is not known as the catalogue went to press before the checklist was finalised. The Museum of Modern Art’s Archive contains an exhibition catalogue annotated with hand-written notes about the final presentation, showing that some projected loans were not secured and other works purchased by collectors close to the museum were added at the last moment. Most press accounts incorrectly list figures taken from the catalogue.

Clement Greenberg, ‘Review of Exhibitions of Marc Chagall, Lyonel Feininger, and Jackson Pollock’, Nation, 27 November 1943, reprinted in Clement Greenberg: The Collected Essays and Criticism. Volume 1: Perceptions and Judgments, 1939–1944, 1993, p.165.

Clement Greenberg, ‘Review of the Exhibition Painting in France, 1939–1946’, Nation, 22 February 1947, reprinted in Clement Greenberg: The Collected Essays and Criticism. Volume 2: Arrogant Purpose, 1945–1949, 1993, p.131.

Greenberg, ‘Two Exhibitions of Marsden Hartley’, Nation, 30 December 1944, reprinted in Clement Greenberg: The Collected Essays and Criticism. Volume 1: Perceptions and Judgments, 1939–1944, 1993, p.246. See also James Hall, ‘Clement Greenberg on English Sculpture and Englishness’, Sculpture Journal, vol.4, 2000, pp.172–7. Other scholars who have discussed Greenberg’s dismissal of Moore include Jennifer Wulfson Bedford, ‘“More Light and Less Heat”: The Intersection of Henry Seldis’ Art Criticism and the Career of Henry Moore in America’, in Rebecca Peabody (ed.), Anglo-American Exchange in Postwar Sculpture 1945–1975, Los Angeles 2011, pp.45–58, and Anne Middleton Wagner, Mother Stone: The Vitality of Modern British Sculpture, London and New Haven 2005. As art historian David Getsy has written, Greenberg’s criticism from 1940 to 1950 showed ‘a special disdain for things British, especially sculpture’ (David Getsy, ‘Tactility of Opticality, Henry Moore or David Smith: Herbert Read and Clement Greenberg on The Art of Sculpture, 1956’, in Rebecca Peabody (ed.) 2011, p.107).

Clement Greenberg, ‘Review of Exhibitions of Jean Dubuffet and Jackson Pollock’, Nation, vol.64, no.5, 1 February 1947, p.137.

Greenberg, ‘Review of Exhibitions of Gaston Lachaise and Henry Moore’, reprinted in Clement Greenberg: The Collected Essays and Criticism. Volume 2: Arrogant Purpose, 1945–1949, 1993, p.126.

See Clement Greenberg, ‘Helter-Skelter: Review of New Directions in Prose and Poetry: 1941 edited by James Laughlin’, New Republic, 13 April 1942, reprinted in Clement Greenberg: The Collected Essays and Criticism. Volume 1: Perceptions and Judgments, 1939–1944, 1993, pp.100–2.

Greenberg, ‘Review of Exhibitions of Gaston Lachaise and Henry Moore’, reprinted in Clement Greenberg: The Collected Essays and Criticism. Volume 2: Arrogant Purpose, 1945–1949, 1993, p.128.

Clement Greenberg, ‘Review of Mondrian’s New York Boogie Woogie and Other New Acquisitions at the Museum of Modern Art’, Nation, 9 October 1943, reprinted in Clement Greenberg: The Collected Essays and Criticism. Volume 1: Perceptions and Judgments, 1939–1944, 1993, p.154. For another view of Greenberg’s criticism of MoMA, see Caroline A. Jones, Eyesight Alone: Clement Greenberg’s Modernism and the Bureaucratization of the Senses, Chicago 2005, pp.88–9.

Clement Greenberg, ‘The Federation of Modern Painters and Sculptors and the Museum of Modern Art’, Nation 12 February 1944, reprinted in Clement Greenberg: The Collected Essays and Criticism. Volume 1: Perceptions and Judgment 1939–1944, 1993, p.183.

Clement Greenberg, ‘The Present Prospects of American Painting and Sculpture’, Horizon, October 1947, reprinted in Clement Greenberg: The Collected Essays and Criticism. Volume 2: Arrogant Purpose, 1945–1949, 1993, p.169. Alice Goldfarb Marquis writes convincingly of the sordid origin of this essay as a deal struck between editor Cyril Connelly and Greenberg over naming the critic in the legal proceedings of Connelly’s divorce from wife, Jean Bakewell Connolly. See Alice Goldfarb, Art Czar: The Rise and Fall of Clement Greenberg, Boston 2006, p.103. Note that 57th Street, with its concentration of commercial galleries and art dealers, was then at the heart of the art market in New York.

Greenberg, ‘Review of Exhibitions of Gaston Lachaise and Henry Moore’, reprinted in Clement Greenberg: The Collected Essays and Criticism. Volume 2: Arrogant Purpose, 1945–1949, 1993, p.127.

Ibid., p.127. The references to specific works may have reflected a pragmatic or political desire to remain on good terms with major collectors. Lois Orwell, one of the most important collectors in New York, owned one of the two Reclining Figures mentioned by Greenberg, while The Helmet 1940 was owned by Roland Penrose, a close friend of Picasso. See Greenberg’s reflections of the role of dealers and collectors in Thierry de Duve, Clement Greenberg Between the Lines, Paris 1996, pp.143–4, and Goldfarb Marquis, Art Czar: The Rise and Fall of Clement Greenberg, 2006, p.206.

Clement Greenberg, ‘Review of Exhibitions of David Smith, David Hare, and Mirko’, Nation, vol.64, no.16, 19 April 1947, p.460.

Clement Greenberg, ‘Review of an Exhibition of Contemporary British Art and of the Exhibition New Provincetown ’47’, Nation, vol.165, no.15, 11 October 1947, p.389.

Clement Greenberg, ‘Review of Exhibitions of Ben Nicholson and Larry Rivers’, Nation, vol.168, no.16, 16 April 1949, p.453.

Clement Greenberg, ‘Feeling is All’, Partisan Review, January–February 1952, reprinted in Clement Greenberg: The Collected Essays and Criticism. Volume 3: Affirmations and Refusals 1950–1956, 1993, p.102.

Clement Greenberg, ‘The Sculpture of Jacques Lipchitz’, Commentary, September 1954, reprinted in Clement Greenberg: The Collected Essays and Criticism. Volume 3: Affirmations and Refusals 1950–1956, 1993, p.181.

Clement Greenberg, ‘A Symposium: The State of American Art’, Magazine of Art, March 1949, reprinted in Clement Greenberg: The Collected Essays and Criticism. Volume 2: Arrogant Purpose, 1945–1949, 1993, p.287.

Clement Greenberg, ‘Polemic Against Modern Art: Review of The Demon of Progress in the Arts by Wyndham Lewis’, New Leader, 12 December 1955, reprinted in Clement Greenberg: The Collected Essays and Criticism. Volume 3: Affirmations and Refusals 1950–1956, 1993, p.254. Tired of Greenberg’s assaults over two decades, Read returned the American’s ire in a letter to the editor of Encounter in February 1963. Greenberg responded, and both letters were published in the same issue.

Clement Greenberg, ‘Sculpture in Our Time’, Arts Magazine, June 1958, reprinted in Clement Greenberg: The Collected Essays and Criticism. Volume 4: Modernism with a Vengeance 1957–1969, 1993, p.58.

Clement Greenberg, ‘Contemporary Sculpture: Anthony Caro’, Arts Yearbook 8, 1965, reprinted in Clement Greenberg: The Collected Essays and Criticism. Volume 4: Modernism with a Vengeance 1957–1969, 1993, p.205.

Clement Greenberg, ‘Interview Conducted by Edward Lucie-Smith’, Studio International, January 1968, reprinted in Clement Greenberg: The Collected Essays and Criticism. Volume 4: Modernism with a Vengeance 1957–1969, 1993, p.279.

See Henry Moore Alice Correia, ‘Critical Voices: Artists’ Responses to the Henry Moore Gift to Tate’, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, 2015, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/henry-moore/alice-correia-critical-voices-artists-responses-to-the-henry-moore-gift-to-tate-r1172242 , accessed 05 June 2015.

Courtney J. Martin is Assistant Professor, History of Art and Architecture at Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island.

How to cite

Courtney J. Martin, ‘‘A sincere academic modern’: Clement Greenberg on Henry Moore’, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www