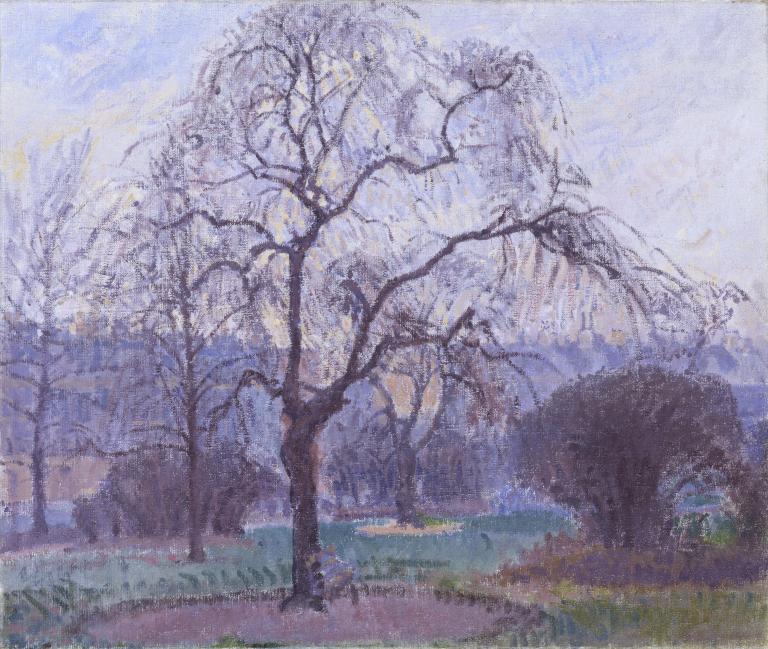

Spencer Gore Mornington Crescent 1911

Spencer Gore,

Mornington Crescent

1911

In 1911–12 Gore lived at 31 Mornington Crescent in north London, a few doors down from Walter Sickert. He made a number of paintings of the area, including this work, which might have been completed in the gardens, now built over. The bare tree and spectral colouring suggest that the time of year was early spring or late autumn.

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

Mornington Crescent

1911

Oil paint on canvas

635 x 765 mm

Bequeathed by Lady Henry Cavendish-Bentinck 1940

N05099

1911

Oil paint on canvas

635 x 765 mm

Bequeathed by Lady Henry Cavendish-Bentinck 1940

N05099

Ownership history

... ; Judge William Evans (1861–1918), probably bought at Carfax Gallery, London, in February 1916; bought at Goupil Gallery, London, May–June 1918 by Lord Henry Cavendish-Bentinck (1863–1931); his sale, Christie’s 12 June 1920 (42, as ‘The Tree’), bought in; his widow, Lady Olivier Cavendish-Bentinck by whom bequeathed to Tate Gallery 1940.

Exhibition history

1916

Paintings by the Late Spencer F. Gore, Carfax Gallery, London, February 1916 (3, as ‘Mornington Crescent Gardens’).

1918

The Judge Evans Collection, Goupil Gallery, London, May–June 1918 (70, as ‘The Tree’).

1920

Advanced Art, Contemporary Art Society, Derby Art Gallery, April–June 1920 (60, as ‘The Tree’).

1928

Exhibition of Paintings by Spencer F. Gore, Leicester Galleries, London, April 1928 (49, as ‘The Tree’).

1942

The Tate Gallery’s Wartime Acquisitions, National Gallery, London, April–May 1942 (39).

1942–3

A Selection from the Tate Gallery’s Wartime Acquisitions, (Council for the Encouragement of Music and the Arts tour), Royal Exchange, London, July–August 1942, Cheltenham Art Gallery, September 1942, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, October 1942, Galleries of Birmingham Society of Arts, November–December 1942, Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, January–February 1943, Victoria Art Gallery, Bath, February–March 1943, National Museum of Wales, Cardiff, March–April 1943, Manchester City Art Gallery, April–May 1943, Philharmonic Hall, Liverpool, May–June 1943, National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh, June 1943, Glasgow Museum and Art Gallery, Kelvingrove, July 1943, Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle upon Tyne, August 1943 (20).

1946–7

Modern British Pictures from the Tate Gallery, (British Council tour), Palais des beaux-arts, Brussels, January–February 1946 (16, reproduced), Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, March 1946 (16, reproduced), Raadhushallen, Copenhagen, April–May 1946 (16, reproduced), Musée du Jeu de Paume, Paris, June–July 1946 (16, reproduced), Musée des beaux-arts, Berne, August 1946 (15, reproduced), Akademie der Bildenen Künste, Vienna, September 1946 (15, reproduced), Narodni Galerie, Prague, October–November 1946 (15, reproduced), Muzeum Narodowe, Warsaw, November–December 1946 (15, reproduced), Galleria d’Arte Moderna, Rome, January–February 1947 (15, reproduced).

1947

Tate Gallery 1897–1947: Pictures from the Tate Gallery Foundation and Exhibition of Subsequent British Painting, Tate Gallery, London, May–September 1947 (5099, reproduced pl.10).

1947–8

Modern British Pictures from the Tate Gallery, (Arts Council tour), Leicester Museum and Art Gallery, September–October 1947, Graves Art Gallery, Sheffield, October–November 1947, Birmingham City Museum and Art Gallery, November–December 1947, Bristol City Art Gallery, January–February 1948, Russell-Cotes Art Gallery, Bournemouth, February–March 1948, Brighton Art Gallery and Museum, March–April 1948, Plymouth Art Gallery, April–May 1948, Castle Museum, Nottingham, May–June 1948, Huddersfield Museum and Art Gallery, June–July 1948, Aberdeen Art Gallery, July–August 1948, Salford Art Gallery and Museum, August–September 1948 (8, reproduced 3).

1951

The Camden Town Group, Southampton City Art Gallery, June–July 1951 (55).

1955–6

Spencer Frederick Gore 1878–1914, (Arts Council tour), Arts Council Gallery, London, November–December 1955, Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle upon Tyne, January 1956, Plymouth City Museum and Art Gallery, February 1956, Southampton City Art Gallery, March 1956, Leeds City Art Gallery, April 1956, Brighton Museum and Art Gallery, December 1956 (29, reproduced).

1960–5

Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle upon Tyne 1960–5, (long loan).

References

1941

John Rothenstein, ‘The Tate Gallery, London, A Patron of Living Art’, Studio, vol.122, September 1941, reproduced p.65.

1947

The Tate Gallery, Fifty Years, London 1947, reproduced pl.10.

1951

Anthony Bertram, A Century of British Painting, 1851–1951, London 1951, p.85.

1951

Hesketh Hubbard, A Hundred Years of British Painting, 1851–1951, London and New York 1951, p.214, reproduced pl.79.

1964

Mary Chamot, Dennis Farr and Martin Butlin, Tate Gallery Catalogues: The Modern British Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, vol.1, London 1964, pp.246–7.

1979

Wendy Baron, The Camden Town Group, London 1979, p.374.

2000

Wendy Baron, Perfect Moderns: A History of the Camden Town Group, Aldershot and Vermont 2000, p.181.

2001

David Peters Corbett, Walter Sickert, London 2001, p.44, reproduced p.43.

Technique and condition

Mornington Crescent is painted in artists’ oil paints on primed stretched canvas. The cloth is plain, open-weave linen. It is attached to the stretcher with evenly spaced tacks that are mostly in their original positions. The canvas has been sized but most of the glue was absorbed into the cloth when applied. White priming extends to the tacking edges and retains the canvas weave texture. It is composed of two distinct layers and seems to have been intended to provide particular (preparatory) surface properties (see also Tate N04675). The stamp of the artists’ colourman Percy Young is impressed into one of the stretcher members. Young’s stamp has been found on a number of stretchers on Gore’s paintings, as well as on the canvas. The painting’s dimensions conform to a standard commercial size, historically described as ‘three-quarter size’. It is possible that Gore purchased the canvas pre-stretched or, given that the mark is on the stretcher and that the canvas edges have been roughly cut (in particular the right-hand edge), that Gore bought a standard-sized stretcher and canvas on the roll and prepared the support himself.

There is no trace of any underdrawing. A variety of techniques have been employed to produce a lively and apparently spontaneous finish, emphasising the play of light across the surface. Fluid paint applied in full strokes was allowed to sink into the interstices of the canvas, retaining the weave texture. In contrast, paint of a paste-like consistency was loaded onto a stiff brush to form raised impasto or scumbled onto the surface with a dry brush, accumulating on the tops of the canvas weave and leaving patches of priming exposed. Where colour has been modified or compositional elements have been overlaid, such as the bench, opaque paint is applied wet-on-dry, so as not to pick up colour from underlying layers. In the later stages paint is also applied wet-in-wet, mixing on the surface, such as the foliage of the trees at the left. Despite the range in handling, there is no evidence of additional media mixed in with the oil to alter the paint properties.

Gore appears to have used artists’ oil tube paints, which in some cases he has mixed to produce opaque colours. The range of pigments used is consistent with the colours listed by Gore in a letter to his pupil John Doman Turner in 1910, with the addition of some cadmium colours: ‘Colours Flake White, Rose madder, Vermilion, Chrome and Lemon Chrome, Ultramarine, Cobalt, Viridian, oxide of Chromium’.1 These were strong, spectrally pure colours, which were readily available from artists’ colourmen, and any black or earth colours have been excluded. This restricted ‘spectral’ palette mirrors that developed by French impressionist painters from the late nineteenth century.

The painting was varnished when acquired by Tate but it had significantly discoloured, distorting the colour values and impairing the visibility of details. The discoloured varnish was removed and the painting has been left unvarnished, which is thought to have been the artist’s original intention.

Maureen Cross and Sarah Morgan

March 2005

Notes

How to cite

Maureen Cross and Sarah Morgan, 'Technique and Condition', March 2005, in Robert Upstone, ‘Mornington Crescent 1911 by Spencer Gore’, catalogue entry, May 2009, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://wwwEntry

Background

Mornington Crescent, northwest quadrant, including No.31 where Spencer Gore rented a room in 1909–12 c.1904

Postcard

90 x 140 mm

Camden Local Studies and Archives Centre

Photo © Camden Local Studies and Archives Centre

Fig.1

Mornington Crescent, northwest quadrant, including No.31 where Spencer Gore rented a room in 1909–12 c.1904

Camden Local Studies and Archives Centre

Photo © Camden Local Studies and Archives Centre

The bare tree suggests that Gore must have painted the Tate painting either before the spring or after the autumn of 1911. The dating of the canvas comes from when it was shown at the Carfax Gallery in 1916, and is presumably accurate as the exhibition was put together with the input of Gore’s widow.

In November 1910, Gore described his recommended way of painting to his pupil John Doman Turner:

I see I overlooked the question about oil painting. There is no reason for muddle. Colours Flake White, Rose madder, Vermillion, Chrome and Lemon Chrome, Ultramarine, Cobalt, Viridian, oxide of Chromium. If painting from drawings, square up drawing on canvas. Settle the colours that you are going to fill the various silhouettes with, mix them and fill the silhouettes with them, remembering that the colour near at hand is stronger than the colour far away. When dry add new drawing in lines a little darker than the colour of the plane on which the drawing is placed. Then repaint getting the colour nearer and so on.

If you start from still life from nature choose something that will remain there for some time. Draw and fill in the silhouette in the same way, only as the thing is before you can observe the colour much more closely. Always mix lots of paint. Never mind waste.4

Gore’s practice was to either paint directly from nature, before the subject, or else to make the painting solely in the studio, based on drawings that had been made on the spot. He held strong views about this way of working. He wrote to Doman Turner:

Every time you shift you produce an entirely fresh composition of course. Of course there are lots of people who shift things about. Move a tree for instance right or left. I can’t do it because it seems to me to throw the whole thing out, the drawing of the shadow of the tree for instance and the things behind it.

I think that when in front of nature what you produce should be exactly what you see and not touched except out of doors. If you set out to arrange or compose things it should be done entirely away from the subject, making of course as many studies from nature as you want.5

If you want to make a painting or an elaborate drawing from a drawing from Nature, you must go to the same place more than one day, and either go on with the same drawing or make many other drawings both of the whole thing and of separate parts, and keep adding to the indoor work. Drawing from memory nearly always leads to some kind of mannerism which may be good if it has enormous knowledge and purpose behind as in J.F. Millet or Leonardo, but it is interesting to notice in Millet and in Daumier and others who did not always get their facts first hand, that such things as the folds of a coat are never very interesting however magnificent the whole figure may be. ... If you have made an intelligent comment on nature you will only confuse it by adding to it indoors. The question is what a thing is like not what it ought to be like.6

Gore ruminated further on the compromise that an artist had to make between precise observation and the way in which the subject was represented:

Black and white are very different things but where does one begin and the other end. The difference between a pure idealist and a pure realist would be that one worked entirely from his imagination such as Blake or Aubrey Beardsley the other entirely from nature or observation such as Courbet or Manet. And you might put someone like Turner exactly between the two. I think it has always been the object of the great imaginative artists to reconcile their ideas with the things they saw. And they would be obliged to do this because painting or sculpture is so entirely bound up with material things that even the purest idealist is bound to put his ideas into some form which he has observed himself or borrowed from someone else. He can’t escape.7

In his review of Gore’s solo exhibition at the Chenil Galleries in 1911, Frank Rutter in the Sunday Times drew particular attention to Gore’s Mornington Crescent pictures. Under the sub-heading ‘The London Landscape’, Rutter wrote:

It is the hall-mark of the true artist that he does not have to wander far afield in search of beauty. He finds it ever waiting for him at his own door, as Mr. Gore has found in his exquisite Mornington Crescent series. To many, I opine, his radiant visions of what is usually held to be a drab and sordid neighbourhood will come as a revelation – a revelation, let us hope, not merely of the beauty of Camden Town but of the greater fact that beauty is not an external phenomenon but something a man carries about with him in his own soul. There are many joyous, expressive paintings in the series.8

Sickert similarly highlighted the series of views Gore made of Mornington Crescent gardens in his obituary:

There was a month of June a few years ago which Gore verily seems to have used as if he had known that it was to be for him the last of its particularly fresh and sumptuous kind. He used it to look down on the garden of Mornington Crescent. The trained trees rise and droop in fringes, like fountains, over the little well of greenness and shade.9

Mornington Crescent

The construction of Mornington Crescent NW1 was begun in 1821 as part of the Fitzroy family estate, and was named after the Earl of Mornington who had married into the Fitzroy family. The northerly part of the crescent, where Gore later lived, was originally called Southampton Street, but this was changed to be part of Mornington Crescent in 1864. Originally it was quite a smart address, and in the nineteenth century had been a place to live for artists and writers: the painter William Clarkson Stanfield (1793–1867) lived at number 36 from 1834 to 1841, Frederick Richard Pickersgill (1820–1900) succeeded him in the same house, and George Cruikshank (1792–1878) lived round the corner at 48 Mornington Place.10 But by the time Gore and Sickert moved there it had started to be a less affluent area, as Rutter’s mention of it being considered ‘a drab and sordid neighbourhood’ suggests.11 Charles Booth inspected the street on 28 October 1898 as part of his survey of London poverty, and recorded in his notebook: ‘Mornington Crescent – of substantial 4 storey houses still probably exclusively of middle class but going down and now largely let in apartments.’12 Booth coloured the street red on his Maps Descriptive of London Poverty (1898–9), indicating the second most affluent level in his system of categorisation, described as ‘Middle class. Well-to-do.’ In the first volume of the final edition of Booth’s Life and Labour of the People in London (1902) he expounded further on his system of categorisation and described red as ‘Lower middle class. Shopkeepers and small employers, clerks and subordinate professional men. A hardworking sober, energetic class.’13

The gardens, originally intended for the enjoyment and leisure of Mornington Crescent’s inhabitants, were built over in 1928 when the Carreras cigarette factory was constructed. Preparation for this development elicited a letter to the Times from Walter Bayes, believing shops were to be built there. Under the heading ‘Spencer Gore’s Grove’, Bayes wrote:

On the way to Westminster I pass at Mornington Crescent a hoarding, behind which preparations are being made for building a row of shops where now are the trees of a garden. There must be many, like myself, who never see them without recalling the bright spirit of Spencer Gore, who, standing at his easel in the most inclement weathers, painted so many charming pictures there to the accompaniment of the hum of the trains.

I am not so sanguine as to suppose artistic sentiment and the amenities of life can stand in the way of commercial progress, but would it not be a graceful gesture, and inexpensive, if the powers who decide such matters should christen the row of shops, which must incongruously replace the trees, ‘Spencer Gore’s Grove’, in memorial to the man whom, more than to anyone else – more, even, than to Mr. Sickert – Camden owed a brief celebrity as a haunt of the muses? That such a memorial would have an ironic flavour is nothing against it. Gore had a nice sense of humour, and we can fancy him chuckling with delight; and, moreover, as I have already admitted, the truly suitable memorial is doubtless impracticable.14

Ownership

The first recorded owner of Mornington Crescent was Judge William Evans (1861–1918). However, it is likely that there was a previous owner because it does not bear the stamp that was applied to all work left in Gore’s studio when he died in 1914. Evans probably did not acquire it until 1916 when it was shown at the Carfax Gallery, as it is not recorded as having been lent by him. Evans was born in Merthyr Tydfil in December 1847 and was on the County Court Bench for mid-Wales from 1897. He was educated at Jesus College, Oxford, where he took honours in Classics and Law, and was called to the Bar by the Inner Temple in 1870. Some time after he joined the circuit of South Wales and Chester and went on commissions to Australia, France and Spain. He wrote on legal subjects but also about Welsh poetry, and died while presiding in court in Oswestry on 15 February 1918.15 Evans put together an eclectic collection of British art in the last twenty years of his life. He had been one of those whom Sickert invited to the Saturday ‘At Homes’ at Fitzroy Street, and Evans bought a large number of paintings and drawings by him. Evans’s widow recalled that ‘when she and her husband ... went to Sickert’s studio he would show them a pile of small sketches and drawings and ask them to take their pick. He would then paint in oil from whatever they chose, usually for £25.’16

Evans also acquired works by Bayes, Bevan, Ginner and Gilman, including Gilman’s Lady on a Sofa exhibited 1910 (Tate N05831). The other Gores that Evans acquired, all oils, were The Mirror. Woman by a Dressing Table c.1908–9 (Tatham Art Gallery, Pietermaritzburg), The Sand Pit (perhaps The Gravel Pit c.1909, now in Kirkaldy Museum and Art Gallery), View through Trees (unidentified) and At a Music Hall (unidentified). Judge Evans’s collection was exhibited at the Goupil Gallery from May to June 1918, where works were evidently offered for sale by his widow. The foreword to the catalogue was written by Charles Aitken, Director of the Tate Gallery, who noted that Evans’s collection

was formed during twenty years by a man who took a real delight in painting, and acquired the works of the younger artists as they painted them, instead of the safe, established dead. The percentage of hits in marking down young genius on the wing is high. Judge Evans bought Steer before he was Steer as we know him; he sought Tonks’ pictures when few others importuned that artist; he secured works by Conder, Ricketts, Shannon, John, Orpen, Nicholson, Connard and Lamb in their early days, and most of the men whose work is now being more and more appreciated, found in him a genial patron in those trying days before their battle with an apathetic public was won ... What Graham, Leyland, Leathart, Plint and Rae did for the Pre-Raphaelite generation, Judge Evans and some others have done for the next.17

Contrasting Evans’s collection with the perceived failures of the Chantrey purchases, the Times described it as ‘interesting as showing what may be done by a buyer of catholic but individual taste who buys only what he likes himself ... He knew a good Sickert when he saw it; and he made very few mistakes, no doubt because he did not buy except when he enjoyed ... And yet his taste was in the main conservative; it differed from that of those who buy for the Chantrey Bequest in that it was his own and was good.’18

Robert Upstone

May 2009

Notes

Reproduced in Spencer Frederick Gore 1878–1914, exhibition catalogue, Anthony d’Offay Gallery, London 1983 (15).

Walter Sickert, ‘A Perfect Modern’, New Age, 9 April 1914, in Anna Gruetzner Robins (ed.), Walter Richard Sickert: The Complete Writings on Art, Oxford 2000, p.355.

Notebook b357, p.25, Booth Collection, Archives of British Library of Political and Economic Science, London School of Economics.

Related biographies

Related essays

- The Camden Town Group and Early Twentieth-Century Ruralism Ysanne Holt

- A History of Camden Town 1895–1914 David Hayes

Related catalogue entries

Related reviews and articles

- Walter Richard Sickert, ‘A Perfect Modern’ The New Age, 9 April 1914, p.718.

How to cite

Robert Upstone, ‘Mornington Crescent 1911 by Spencer Gore’, catalogue entry, May 2009, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www