Walter Richard Sickert Belvedere, Bath c.1917

Walter Richard Sickert,

Belvedere, Bath

c.1917

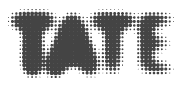

This view looks down onto Bath from Belvedere, part of the Lansdown Road just east of the Royal Crescent. Shops and houses line either side of the street leading into town, and a horse and cart drive into the frame on the right side of the painting. Sickert depicts everyday details – such as a ladder leaning against the façade of a building – with as much care as the architecture and foliage. He spent two summers in Bath in 1917–18 with his second wife Christine, when crossing the Channel was not possible in wartime.

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Belvedere, Bath

c.1917

Oil paint on canvas

711 x 711 mm

Bequeathed by Lady Henry Cavendish-Bentinck 1940

N05087

c.1917

Oil paint on canvas

711 x 711 mm

Bequeathed by Lady Henry Cavendish-Bentinck 1940

N05087

Ownership history

Purchased from the artist by Lord Henry Cavendish-Bentinck, London, c.1918–25; by descent to his wife, Lady Henry Cavendish-Bentinck, on his death 6 October 1931, by whom bequeathed to Tate Gallery 1940.

Exhibition history

1925

Special Retrospective Exhibition (1806–1924) and the Seventy-First Exhibition of the New English Art Club, Spring Gardens Gallery, London, January–February 1925 (172, as ‘Bath’).

1936

A Loan Exhibition of Paintings & Drawings, St John Ambulance Hall, Kendal, April–May 1936 (17, as ‘View of Bath’).

1937

Empire Exhibition, British Council, Johannesburg Art Gallery, South Africa, September 1936–January 1937 (672, as ‘Bath’, reproduced).

1938

La Peinture anglaise XVIIIe & XIXe siècles, British Council, Palais du Louvre, Paris 1938 (117, as ‘Bath’, reproduced).

1942

The Tate Gallery’s Wartime Acquisitions, National Gallery, London, April–May 1942 (123, as ‘Bath’).

1942–3

A Selection from the Tate Gallery’s Wartime Acquisitions, (Council for the Encouragement of Music and the Arts tour), Royal Exchange, London, July–August 1942, Cheltenham Art Gallery, September 1942, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, October 1942, Galleries of Birmingham Society of Arts, November–December 1942, Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, January–February 1943, Victoria Art Gallery, Bath, February–March 1943, National Museum of Wales, Cardiff, March–April 1943, Manchester City Art Gallery, April–May 1943, Philharmonic Hall, Liverpool, May–June 1943, National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh, June 1943, Glasgow Museum and Art Gallery, Kelvingrove, July 1943, Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle upon Tyne, August 1943 (85, as ‘Bath’).

1946–7

Modern British Pictures from the Tate Gallery, (British Council tour), Palais des Beaux-Arts, Brussels, January–February 1946 (88), Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, March 1946 (88), Raadhushallen, Copenhagen, April–May 1946 (88, reproduced), Musée du Jeu de Paume, Paris, June–July 1946 (88), Musée des Beaux-Arts, Berne, August 1946 (91), Akademie der Bildenden Kunste, Vienna, September 1946 (92), Narodni Galerie, Prague, October–November 1946 (92), Muzeum Narodwe, Warsaw, November–December 1946 (92), Galleria d’Arte Moderna, Rome, January–February 1947 (92), Tate Gallery, London, May–September 1947 (5087, as ‘Bath’).

1947–8

Modern British Pictures from the Tate Gallery, (Arts Council tour), Leicester Museum and Art Gallery, September–October 1947, Graves Art Gallery, Sheffield, October–November 1947, Birmingham City Museum and Art Gallery, November–December 1947, Bristol City Art Gallery, January–February 1948, Russell-Cotes Art Gallery, Bournemouth, February–March 1948, Brighton Art Gallery and Museum, March–April 1948, Plymouth Art Gallery, April–May 1948, Castle Museum, Nottingham, May–June 1948, Huddersfield Museum and Art Gallery, June–July 1948, Aberdeen Art Gallery, July–August 1948, Salford Art Gallery and Museum, August–September 1948 (59, as ‘Bath’).

1960

Sickert: Paintings and Drawings, (Arts Council tour), Tate Gallery, London, May–June 1960, Southampton Art Gallery, July 1960, Bradford City Art Gallery, July–August 1960 (150).

1961–2

English Landscape Painters, Phoenix Art Museum, Arizona, December 1961–January 1962 (68).

1965–89

Government Art Collection, c.1965–89 (long loan).

1989–90

W.R. Sickert: Drawings and Paintings 1890–1942, Tate Gallery, Liverpool, March 1989–February 1990, Tate Gallery, London, July–September 1990 (31, reproduced).

2004

Walter Richard Sickert: The Human Canvas, Abbot Hall Art Gallery, Kendal, July–October 2004 (33, reproduced).

References

1927

J.B. Manson, ‘Walter Richard Sickert, A.R.A.’, Drawing and Design, vol.3, July 1927, reproduced p.6.

1941

Robin Ironside, ‘The Tate Gallery: Wartime Acquisitions’, Burlington Magazine, vol.78, February 1941, p.57, reproduced pl.II D, as Street in Bath.

1943

Lillian Browse and R.H. Wilenski, Sickert, London 1943, p.56, reproduced pl.48.

1957

Sickert: An Exhibition of Paintings, Drawings and Prints, exhibition catalogue, Graves Art Gallery, Sheffield 1957, p.16.

1960

Lillian Browse, Sickert, London 1960, pp.79, 102.

1964

Mary Chamot, Dennis Farr and Martin Butlin, Tate Gallery Catalogues: The Modern British Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, vol.2, London 1964, pp.628–9.

1970

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942: Catalogue of the Islington Libraries Collection, London 1970, p.8.

1973

Wendy Baron, Sickert, London and New York 1973, p.372.

1975

Geoffrey Grigson, Britain Observed: The Landscape through Artists’ Eyes, London 1975, reproduced pl.127.

1992

Wendy Baron and Richard Shone (eds.), Sickert: Paintings, exhibition catalogue, Royal Academy, London 1992, p.262, reproduced fig.181.

2006

Wendy Baron, Sickert: Paintings and Drawings, New Haven and London 2006, no.493.1.

Technique and condition

Belvedere, Bath is painted on a white, commercially primed linen cloth, which has a fine plain weave but has been poorly made with some double threads and some flaws with excessively open weave. The canvas has been re-stretched, probably by the artist, rotating the painting very slightly anticlockwise (seen from the front) on the stretcher. The prepared canvas was squared up with pencil lines 3½ inches apart, probably to transfer the design from a drawing. The image is painted thinly in places, initially to draw the composition and then to fill in the broad shadows and lights. White primer is left visible between patches of colour and there is thick impasto and strong brushmarking of paint applied from a loaded brush in many places. The paint is fairly lean but has more gloss where it is impasted. The technique is direct and impressionist in style. The work was left in a raw state with the pencil squaring-up lines visible in places. The surface is left unvarnished.

Stephen Hackney

July 2004

How to cite

Stephen Hackney, 'Technique and Condition', July 2004, in Nicola Moorby, ‘Belvedere, Bath c.1917 by Walter Richard Sickert’, catalogue entry, September 2005, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://wwwEntry

Early on in his career Walter Sickert had formed the habit of leaving London during the summer months and vacationing in a chosen location, usually Dieppe, which he adopted as a second home. During the war years, however, Sickert was unable to cross the Channel and was forced to seek a new holiday destination. The search for a suitable alternative led him to Brighton, Sussex in 1915 and Chagford, Devon in 1916. Finally in 1917 he visited the historic city of Bath and liked it so much that he established himself there in 1918. He and his wife, Christine, rented a house named ‘The Lodge’ at Entry Hill, and a studio room at 10 Bladud Buildings in the heart of town. By the following year, the war was over and Sickert was able to resume his annual trip to France. Bath evidently retained happy memories for him, however, and he returned twenty years later to live in nearby Bathampton, which was to be his last home.

In his summer retreat Sickert was seeking a place where he could rest and work, find inspiration in new sights and yet strengthen ties and connections to the place, revelling in a sense of familiarity and belonging. With some places he exhausted the possibilities and resources quickly and moved on, while with others he returned year after year. Bath had long been famous for its Roman baths and Georgian architecture and Sickert was probably drawn to its reputation as a place for restorative recreation and rest. A contemporary guide to the area describes the aesthetic attractions of the city and the particular quality of the light to be found there:

It lies in a hollow among the beautiful hills; its charming terraces and crescents, even as seen from the railway, are an alluring view, especially when evening is covering them in its haze, we cannot pass through it without a stirring of the imagination, a conjuring of old ghosts ... Bath’s hills ... are gentle and pastoral, and they give the town its own peculiar climate which some persons find relaxing ... there is often a touch of dream, of unreality, fitly clinging to a spot whose true life seems to belong to the past.1

Sickert found Bath both relaxing and stimulating. He was enchanted by the elegance of the Regency terraces and crescents surrounded by Somerset countryside and the Avon valley. There was also the additional attraction of his own family connection to the place: his great-uncle, Mr John Sheepshanks, had once lived in a house at the end of Camden Crescent.2 Sheepshanks was famous for founding the paintings collection of the South Kensington Museums (later the Victoria and Albert Museum) with his bequest of over two hundred works to the nation in 1857. ‘Bath is it!’ the artist wrote to Ethel Sands. ‘There never was such a place for rest & comfort & leisurely work. Such country & such town. And the mellifluous amiability of the west-country gaffers and maidens, all speaking the dialect which became the American we know and love!’3 In 1918, he persuaded his latest protégée, Nina Hamnett (see Tate N05288) to join him, eager for her to share his enthusiasm for the city. He found lodgings for her in town:

a little house ... half way down Beechen Cliff, 2 minutes from station and five from pump room ... The place is divine. It is on our way down to town ... The beauty of the place is incredible. My walk down after breakfasting à la Anglaise in the kitchen at about 6 is like a German woodcut of the views down through beech trees on the elaborate town ... You could walk in these gardens and orchards in perfect peace. Such roofs, such roses, such contorted walls ... such bracing air.4

The visit did not work out as happily as either party had anticipated.5 Sickert was too self-absorbed to keep the gregarious Hamnett entertained and she failed to show as much interest in adopting his painting regime as he had hoped. His didactic efforts fell on deaf ears and she eventually departed back to London leaving Sickert still as enchanted as ever with his Bath motifs.

Sickert seems to have found the city a particularly conducive location for work. He established a daily routine of drawing, painting, bathing and painting again. Belvedere, Bath is one of a number of landscapes Sickert produced during his two summers in the city and depicts the view looking down from Belvedere, part of the Lansdown Road, just east of the Royal Crescent. The scene shows the sweeping curve of the road with the shops and houses on either side of the street. As with his earlier Dieppe townscapes Sickert favoured certain locations, which he drew and painted repeatedly. Besides the Belvedere, his favourite subjects were Pulteney Bridge, Landsdown Crescent and Mr Sheepshank’s House. The Bath pictures were well received in London. The critic of the Times wrote that ‘Mr Walter Sickert ... seems to have been enchanted by the soft Western air and the warm Western light. He gives us colour that might be pretty if it were not beautiful.’6 The Evening Standard expressed the hope that ‘Mr Sickert will paint many pictures of a city that thoroughly deserves him’.7

In the background of Belvedere, Bath Sickert painted the mauve-green mass of the hill known as Beechen Cliff, a popular tourist spot due to the panoramic vista it afforded over the city. By painting the view towards Beechen Cliff from the town, instead of vice versa, Sickert is subverting the remit of traditional landscape painting. The elegant picturesque qualities for which Bath is so famous are relinquished in favour of a humbler, everyday view of the working life of the city. Details such as the ladder leaning against the front of one of the buildings feature in the painting with as much importance as the architecture or natural features such as trees. One of the first buildings on the right at the crest of the hill has a shop front window onto the street and a sign which reads ‘[?]R. Pavel, Chemist’. The left-hand foreground of the painting has been left bare deliberately to emphasise the sweeping curve of the road, leading the eye down the hill to the centre of the painting. Sickert’s solution to the technical difficulty of describing the tricky perspective of the descending view is to include enough buildings in the middle ground that recede in size. In the right-hand corner is the figure of a man in a bowler hat standing behind a small horse or pony pulling a wheeled cart. The animal appears to be standing still with its feet braced firmly apart as though anxious to venture further down the steep decline.

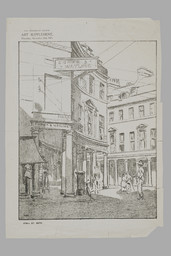

Like most of Sickert’s paintings at this time, Belvedere, Bath was conceived and executed from drawings, a method which the artist believed achieved the best results. He rejected the practice of painting from life as too undisciplined and tried to convert his fellow artists to his technique. In a letter to Hamnett he condemned ‘prima’ painting, explaining:

You couldn’t, for instance, do a certain view of Bath I am doing from where I sat for the studies in the street, and the wind and the dust and the changing light. Besides carts and horses don’t stand still while you execute them in oil.8

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Beechen Cliff, Bath not dated

Pen and black ink and graphite on paper

240 x 227 mm

British Museum, London

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © The Trustees of the British Museum

Fig.1

Walter Richard Sickert

Beechen Cliff, Bath not dated

British Museum, London

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © The Trustees of the British Museum

Sickert painted more than one version of the view from the Belvedere. In addition to Tate’s painting there are two other similar works, The Belvedere or Beechen Cliff, Bath c.1916–18 (private collection, formerly Sir George Sutton),14 and a smaller version, Belvedere, Bath (formerly Hugh Beaumont Esq.).15 There is also an oil study on board, View of Bath from Belvedere (Victoria Art Gallery, Bath),16 which broadly sketches out the compositional elements of the scene, and another small panel (Tatham Art Gallery, South Africa).17 It is not known in which order these paintings were completed but, since there is very little alteration between the pictures, Sickert probably repeated the scene because it was a saleable subject.

Nicola Moorby

September 2005

Notes

Related biographies

Related archive items

How to cite

Nicola Moorby, ‘Belvedere, Bath c.1917 by Walter Richard Sickert’, catalogue entry, September 2005, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www