Walter Richard Sickert Brighton Pierrots 1915

Walter Richard Sickert,

Brighton Pierrots

1915

This view from stage right shows a vaudeville troupe of pierrots performing atop a temporary wooden platform under electric lights on the Brighton seafront at dusk in late summer. A pierrette in acid pink plays the upright piano while a pierrot in traditional blue-green pantaloons, ruffled collar and cap sits waiting nearby. The two figures playing to a depleted audience are dressed in contemporary red suits and straw boaters, the nearer of the pair almost entirely obscured by a column wrapped in bright streamers. The perceived joviality and awkward arrangement of the tragic-comic characters can be read as an expression of wartime tension; gunfire on the Front in Flanders was sometimes audible across the Channel during the First World War.

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Brighton Pierrots

1915

Oil paint on canvas

635 x 762 mm

Inscribed by the artist ‘St. 1915.’ in black paint bottom left

Purchased with assistance from the National Art Collections Fund and the Friends of the Tate Gallery 1996

T07041

1915

Oil paint on canvas

635 x 762 mm

Inscribed by the artist ‘St. 1915.’ in black paint bottom left

Purchased with assistance from the National Art Collections Fund and the Friends of the Tate Gallery 1996

T07041

Ownership history

Commissioned from the artist by Sir William and Lady (later Rt. Hon. the Earl and Countess) Jowitt in 1915; thence by descent; sold Christie’s, London, 4 November 1983 (lot 42) to Fine Art Society, London; sold at their Spring ’84 exhibition, May 1984 (24) to Frederick Koch; by whom sold to Christie’s, London, 12 March 1993 (lot 85); bought Fine Art Society on behalf of Mary and Will Richeson, Santa Barbara; by whom sold through Fine Art Society, London, to Tate Gallery 1996.

Exhibition history

1916

Paintings by Walter Sickert, Carfax Gallery, London, November 1916 (9, as ‘Brighton 1915’).

1920

Sickert, Chelsea Book Club, London, July 1920 (no catalogue found).

1940

British Painting Since Whistler, National Gallery, London, March–August 1940 (501, as ‘The Front at Brighton’).

1941

A Whistler and Early Twentieth Century Oils, National Gallery, London 1941 (31, as ‘The Front at Brighton’).

1941

Sickert, National Gallery, London, August–December 1941 (50, as ‘The Front at Brighton’).

1942

Sickert, 1860–1942: Paintings, Drawings and Prints, Temple Newsam, Leeds, March–May 1942 (172, as ‘Brighton’).

1942

Sickert, Council for the Encouragement of Music and the Arts, Alexandra House, London 1942 (21, as ‘Brighton’).

1950

Sickert Exhibition, Hove Museum of Art, August–September 1950 (34).

1951

The Camden Town Group, The Art Gallery, Civic Centre, Southampton, June–July 1951 (120).

1957

Sickert: An Exhibition of Paintings, Drawings and Prints, Graves Art Gallery, Sheffield, September–October 1957 (45).

1962

The Painter’s Brighton, Brighton Art Gallery and Museum, July 1962 (70, reproduced on front cover).

1973

Sickert, Fine Art Society, London, May–June 1973, Fine Art Society, Edinburgh, June–July 1973 (76).

1976–7

A Terrific Thing: British Art 1910–16, Norwich Castle Museum, October–November 1976, Southampton City Art Gallery, November 1976–January 1977, Oxford Museum of Modern Art, January–February 1977 (21).

1984

Spring ’84, Fine Art Society, London, May 1984 (24, reproduced).

1992–3

Sickert: Paintings, Royal Academy, London, November 1992–February 1993, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, February–May 1993 (88, reproduced, and on back cover).

1993

The Sussex Scene: Artists in the Twentieth Century, Towner Art Gallery, Eastbourne, July–August 1993, Hove Museum and Art Gallery, August–October 1993 (122, reproduced).

1994–5

Channel Crossings, Santa Barbara Museum of Art, September 1994–May 1995 (no catalogue).

1995

Fine Art Society, London, November 1995.

1998

Two British Impressionists: Walter Sickert and Philip Wilson Steer, Norwich Castle Museum, January–April 1998 (27, reproduced).

1998–9

Lucien Pissarro et le post-impressionisme anglais, Musée de Pontoise, November 1998–March 1999, Chateau-Musée, Dieppe, March–June 1999 (48, reproduced).

2004

The Great Parade: Portrait of the Artist as Clown, Grand Palais, Paris, March–May 2004, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, June–September 2004 (25, reproduced).

2005

A Picture of Britain, Tate Britain, London, June–September 2005 (not in catalogue).

2008

Modern Painters: The Camden Town Group, Tate Britain, London, February–May 2008 (94, reproduced).

2010

The Art of Walter Sickert, The Lightbox, Woking, May–July 2010 (no catalogue).

References

1941

Robert Emmons, The Life and Opinions of Walter Richard Sickert, London 1941, p.185.

1943

Lillian Browse and Reginald Howard Wilenski, Sickert, London 1943, p.29.

1949

Notes and Sketches by Sickert from the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, exhibition catalogue, Arts Council, London 1949, p.19.

1951

Sickert: Forty of his Finest Paintings, exhibition catalogue, Roland, Browse and Delbanco, London 1951, p.7.

1955

Anthony Bertram, Sickert, London and New York 1955, reproduced pl.33.

1960

Lillian Browse, Sickert, London 1960, p.20, no.69, reproduced pl.69.

1962

‘Sickert at Brighton’, Apollo, vol.77, no.5, July 1962, p.404.

1973

Wendy Baron, Sickert, London and New York 1973, pp.151–2, 369.

1976

Denys Sutton, Walter Sickert: A Biography, London 1976, p.181.

1988

Hugh David, The Fitzrovians: A Portrait of Bohemian Society 1900–55, London 1988, p.69.

1988

Richard Shone, Sickert, Oxford 1988, reproduced pl.48.

1994

Walter Taylor 1860–1943: A Friend of Sickert, exhibition catalogue, Michael Parkin Gallery, London 1994, [p.2].

1999

Stephen Hackney, Rica Jones and Joyce Townsend (eds.), Paint and Purpose: A Study of Technique in British Art, London 1999, p.120.

2001

David Peters Corbett, Walter Sickert, London 2001, p.47, reproduced fig.39.

2004

Matthew Sturgis and Hannah Neale, Walter Richard Sickert: The Human Canvas, exhibition catalogue, Abbot Hall Art Gallery, Kendal 2004, p.70.

2005

Matthew Sturgis, Walter Sickert: A Life, London 2005, p.479, reproduced in between pp.544–5.

2005

‘Mind Field: Michael Palin on Walter Richard Sickert’s “Brighton Pierrots” (1915)’, Tate Etc., no.4, Summer 2005, p.97, reproduced.

2006

Wendy Baron, Sickert: Paintings and Drawings, New Haven and London 2006, no.472.1, pp.104, 139, 441–2.

2006

Nicola Moorby, ‘“Poor abraded butterflies of the stage”: Sickert and the Brighton Pierrots’, Tate Papers, Spring 2006, http://www.tate.org.uk/research/tateresearch/tatepapers/06spring/moorby.htm.

2009

Nicola Moorby, ‘London to Brighton: The Indian Summer of the Camden Town Group’, in Lara Feigel and Alexandra Harris (eds.), Modernism on Sea: Art and Culture at the British Seaside, Oxford 2009, pp.56, 63–9, reproduced pl.2 between pp.98–9.

Technique and condition

Walter Sickert visited the beach entertainments in Brighton every night during August and September 1915 making many pencil and pen sketches. The two versions of Brighton Pierrots were painted after the artist had returned to London, not in front of the scene en plein air, but constructed from drawings and from memory. Preliminary designs, sometimes known as amenées, gave him the control and versatility to create interesting paintings.

Sickert began his painting on a commercially prepared white pre-primed ‘Winton’ canvas with a Winsor and Newton stamp on the reverse. He was experimenting with a method that he termed a ‘camaieu’ preparation, which involved laying-in, on top of the plain white ground, flat unmodulated areas of pale opaque colours to define the lights and shadows of the intended composition. Sickert recommended white with cobalt for the highlights and white with three strengths of Indian red for the shadows. The exact colours were not important provided the lay-in remained light and contrasted with intended overlayers. If the shadows were too dark they would deaden the next coat. Small areas left uncovered provide a simultaneous contrast with the final layer. In this painting the clearest effect of a camaieu (a mixture of lead white and Mars red) can be seen beneath the lean dull olive brown scrubbed top layer in the stage. Small areas of camaieu are also visible between patches of colour at the end of brushstrokes, and uncovered white ground is visible around the Pierrots. By contrast, much of the sky is unbroken and painted in a fatter more finished paint, entirely covering any underpaint.

Sickert applied his oil paint opaque and lean in a stiff paste (pâte) using a hogshair brush with a minimum of turpentine or petroleum spirit. Each area of paint was left to dry thoroughly and then reworked, either modified or completely overpainted, with more opaque paste. In places the stiffly applied paint has bounced across the canvas texture and has broken up at the end of each stroke.

Tate’s painting is the second version of Brighton Pierrots. This version is a flatter and simplified rendition; some of the detail has been omitted and the modelling of the shadows is reduced. That it is a more spontaneous work is evident from the cavalier treatment of the performer’s blazer lapel and the missing collar of the seated figure. But it is not clear why Sickert introduced another figure to the left of the pianist, and then rubbed it out. He has not bothered to paint over this rubbed-out figure. It seems likely that he painted this second version unusually freely. As the amount of reworking has been kept to a minimum, there is less evidence of the struggle that is often a feature of Sickert’s work.

The tonal range of the sky and background are kept low, but on stage the powder-pink suits and the decorated stage awnings are cool and vibrant, with the two blazered figures modelled in flat half-shadow against the light. The low-toned areas were achieved by adding ivory black to the colours. Sickert departs from his usual practice in his use of pure colours unmixed with black for the lime-lit parts of the composition, for instance, the pink and lime green of the pole. The pink consists of lead white, an organic pink, vermilion and cobalt blue, and the lime green is a mixture of lead white and chrome yellow.

Little effect of the white ground remains visible; the only white paint, incompletely mixed with yellow on the brush, has been added as highlights, most obviously for the lime-lights and the performers’ collars, but only sparingly.

Acknowledgements

Pigment analysis was carried out by Joyce Townsend using optical microscopy and EDX. This conservation report is adapted from a chapter by Stephen Hackney, in Stephen Hackney, Rica Jones and Joyce Townsend (eds.), Paint and Purpose: A Study of Technique in British Art, London 1999.

Stephen Hackney

March 2010

How to cite

Stephen Hackney, 'Technique and Condition', March 2010, in Nicola Moorby, ‘Brighton Pierrots 1915 by Walter Richard Sickert’, catalogue entry, February 2004, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://wwwEntry

Background

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Brighton Pierrots 1915

Oil paint on canvas

640 x 768 mm

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Fig.1

Walter Richard Sickert

Brighton Pierrots 1915

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

The two versions of Brighton Pierrots are very similar and only differ in small details of composition and appearance. In the original painting, there are streaks of light emanating from one of the overhanging stage lights and the foremost pierrot is holding a short walking cane. Tate’s later version is brighter and more acidic in colour with reduced modelling in the shadows. The definition of forms is also somewhat stronger and there are areas of simplified detail, such as the starker outlines of the stage footlights. Tate’s Brighton Pierrots is therefore perhaps rather more dramatic and bleak in effect. In addition, there are visible traces of another pierrot figure standing beyond the pink pierrette at the piano which Sickert has partially rubbed out but not entirely painted over.

Sickert in Brighton

The painting dates from 1915, when, for the first time in over seventeen years, Sickert had to forgo his annual excursion to Dieppe and the surrounding area. He had been in Envermeu on the declaration of the First World War but fled to England in August 1914, just prior to the German invasion, and did not return to France again until 1919. Forced to remain on the English side of the Channel by the ongoing hostilities and denied access to Dieppe, the town for which he felt such enduring affection, Sickert opted instead to stay at the English south coast resort of Brighton. This Sussex seaside town offered many of the same pleasures as its French counterpart: fresh air and bathing; elegant lawns and promenades; and a wide variety of entertainments. Sickert had visited Brighton during 1913 when he made a speech at the opening of an exhibition selected and arranged by the Camden Town Group, English Post-Impressionists, Cubists and Others. In 1914 he returned for a short break with his wife. His decision in August 1915 to replace his usual continental summer trip with a few weeks in Brighton was undoubtedly prompted by the similarities he found with his beloved Dieppe.

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

Brighton Pier 1913

Oil paint on canvas

635 x 763 mm

Southampton City Art Gallery

Photo © Southampton City Art Gallery, Hampshire, UK / The Bridgeman Art Library

Fig.2

Spencer Gore

Brighton Pier 1913

Southampton City Art Gallery

Photo © Southampton City Art Gallery, Hampshire, UK / The Bridgeman Art Library

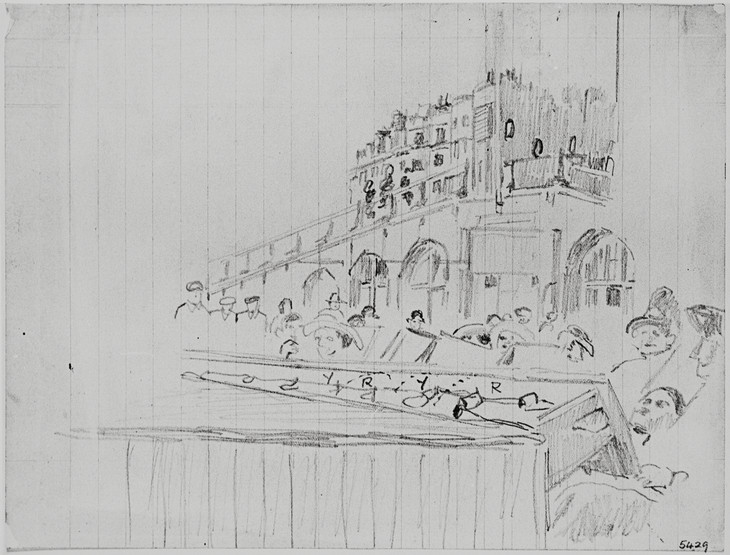

Related sketches

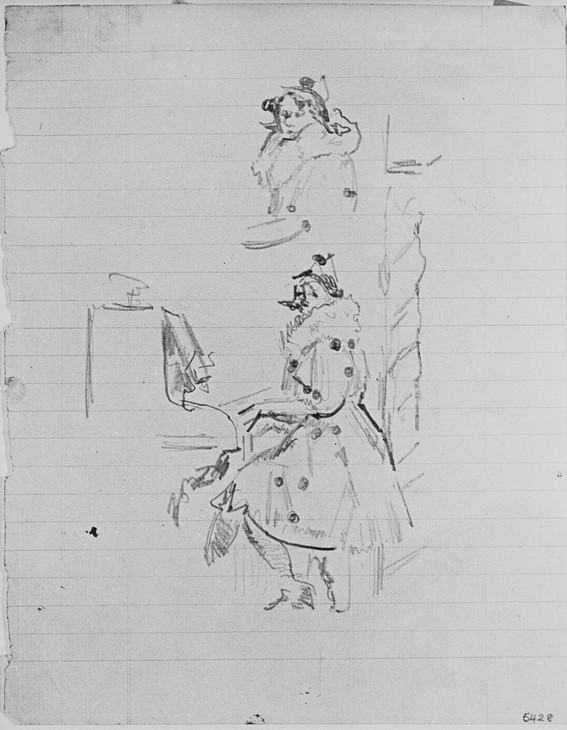

There are three known drawings related to the picture. Two pencil sketches on ruled paper, both in the collection of the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool (figs.3 and 4), were probably drawn by Sickert on the spot as he was sitting beside the stage. One shows the crowd watching the performance and the view up towards the promenade as in the painting. The other depicts the figure of the pierrette playing the piano.10 The third study is a small outline sketch of the entire composition in pen and ink on blue notepaper (whereabouts unknown).11 This was originally in the collection of Morton Sands and it is probably the drawing Sickert was referring to in a letter to Ethel Sands in 1915: ‘I enclose a sketch of a picture 30 x 25 I am at work on. The subject is amazing but what I have got on canvas seems mediocre to me.’12 The drawing is therefore an illustration of the painting rather than a preparatory composition sketch, although it remarkably omits the foreground pierrot behind the pole, proving that he was a late addition. The artist also wrote in another letter that he was repainting the picture on a ‘fresh canvas after the kind of day to day rehearsal with which one registers daily impressions’.13 This suggests that Sickert might have abandoned the first ‘mediocre’ canvas because he had not effectively captured the mood he was after and that the Morton Sands / Ashmolean Brighton Pierrots was actually his second attempt at the subject. A further possibility is that Sickert then resurrected the first discarded picture in order to complete the commission for the Jowitts,14 although there is nothing in the technical examination of the two paintings to support this.

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Audience on the Beach 1915

Pencil on ruled ledger paper

173 x 226 mm

Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Image provided by National Museums Liverpool with kind permission of the Artist’s Estate

Fig.3

Walter Richard Sickert

Audience on the Beach 1915

Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Image provided by National Museums Liverpool with kind permission of the Artist’s Estate

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Pierrette at the Piano 1915

Pencil on ruled ledger paper

228 x 172 mm

Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Image provided by National Museums Liverpool with kind permission of the Artist’s Estate

Fig.4

Walter Richard Sickert

Pierrette at the Piano 1915

Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Image provided by National Museums Liverpool with kind permission of the Artist’s Estate

Sickert’s method of painting was to establish a composition derived from images selected from his source material of large numbers of drawings. It is therefore likely that the artist completed many more sketches in Brighton which are now either lost or unidentified. One possible example is a pen and ink sketch showing a stage against the backdrop of a large marquee with the heads of the audience in the foreground (private collection).15 The platform is crowded with a riotous variety of performers including a masked harlequin, a dwarf and a lady in a revealing evening dress and possibly records the performance of another Brighton pierrot company.

Colour

By comparison with much of Sickert’s other painting to date, Brighton Pierrots resonates with vibrant colour. Sickert’s earlier work had been characterised by the use of dark colours and tones. His Camden Town colleague, Wyndham Lewis, ironically recalled Harold Gilman’s horror at Sickert’s subdued palette: ‘He [Gilman] would look over in the direction of Sickert’s studio, and a slight shudder would convulse him as he thought of the little brown worm of paint that was possibly, even at that moment, wriggling out onto the palette that held no golden chromes, emerald greens, vermilions.’16 The brilliance of Brighton Pierrots is achieved through the contrast between colours mixed with black, in areas of low tone and shadow, and pure unmixed colours in the highlights, such as the pink of the pierrette’s dress.17

The pigment has been applied with a method which Sickert increasingly eulogised as the ideal way to paint in oil, a technique he called the ‘camaïeu’ (cameo) preparation. The lights and shadows of a composition were first coarsely blocked out on the primed canvas with two contrasting pale colours, in this case light blue and pink.18 When this layer was bone dry, it was almost entirely covered by thin layers of opaque paint scrubbed hard across the surface. Small areas of the lighter camaieu would remain visible beneath the overlayers, intensifying the depth and contrast of the colours. It has been suggested that Brighton Pierrots represents a release into colour after weeks spent concentrating on the discipline of black and white etching.19 Sickert had written to Ethel Sands prior to his Brighton visit ‘the restraints of etching have given me a new letch for the brush’.20 Brighton Pierrots represents a significant development in Sickert’s career because it marks the beginning of a change in his work and demonstrates his abilities as a colourist. The camaieu method of painting gave Sickert an unmistakable style and dominated his later work of the 1920s and 1930s.

Seaside Pierrots

‘Pierrot’ groups first appeared in Britain’s coastal resorts during the 1890s and became an established feature of seaside vaudeville entertainment until the Second World War. Each troupe occupied its own pitch and performed on a portable wooden stage, usually erected on the beach.21 The performers wore costumes derived from the traditional pierrot character of French pantomime: loose pantaloons and tunics with ruffles around the neck, big black buttons or pompoms, and a conical shaped hat.22 Unlike the slightly risqué nature of music hall acts, pierrot troupes offered hearty family entertainment, comic sketches, dancing and songs. A contemporary fictional story by Paul Herring, The Pierrots on the Pier, published in 1914 by ‘Hulton’s 3d novels’ offers a description of a typical pierrot show:

The pierhead at Seathorpe was crowded, all available deck chairs and pier seats were claimed, and groups of people were standing, making an extensive awning of sunshades and straw hats in the blaze of morning sunshine ... Three white figures with banjo and mandoline gathered near the piano. The marionettes bowed to the company and Morrice Grey seated himself at the piano. As an overture, the minstrels gave a selection from the Pearl Girl [a popular musical by Howard Talbot, written in 1913]. Then they commenced their original programme. To the tinkle of his own mandoline Dick related a dainty romance of Pierrot in difficulties ... Morrice Grey varied the programme by wonderfully clever imitations of music hall celebrities and famous actors ... Afterwards there were rag-time songs, selections from the latest musical comedies, a tango medley and a costume recital ... and a topical song of pantomime pattern with verses touching on questions of the hour, and a jolly chorus, “Although the Deutsches Kaiser may bluster and despise her, / Brittania’ll take the Germans down a peg.”23

The two foremost men, one of whom is partially concealed by a pink pole decorated with blue ribbon, are dressed in red suits and wear straw boaters. At the beginning of the twentieth century, it became common for pierrots to incorporate into the second half of their act contemporary clothes, such as blazers and boaters, or evening dress with top hats.24 Traditional costume is worn by a pierrot in green sitting at the back of the stage and a pierrette in a pink dress who is playing the piano. The crossed legs and booted feet of a fifth figure are visible at the bottom left-hand corner of the painting. The stage has been constructed facing away from the sea towards the promenade, probably at a point between the Palace Pier and the West Pier. Just visible through the legs of the nearest pierrot is a figure standing beside the right-hand corner of the stage and carrying what looks like a hat or tray. This is possibly a person selling refreshments although it could also be the troupe’s ‘bottler’. Only members of the audience seated in deck chairs were asked to pay a nominal fee to watch the act. Standing onlookers were invited to contribute to a hat circulated by a member of the troupe known as the collector or ‘bottler’,25 encouraging tips with easy banter and jokes.

The art historian Richard Shone has suggested that Sickert’s painting shows a concert party by one of Brighton’s most enduring and successful pierrot companies, the ‘Highwaymen’, run by a local entertainer, Jack Sheppard.26 The Highwaymen were a regular fixture of the Brighton holiday season from 1904 and maintained their performance record throughout the First World War despite the diminishing number of tourists to the town. Contemporary photographs of the group show that it was comprised of between six and eight men and women.27 The troupe continued to perform for many years after the First World War when they were known as ‘Jack Sheppard’s Entertainers’.28 Their most famous ‘bottler’ was the comedian Max Miller (1894–1963) who launched his career with the group in 1919. One of their established alfresco pitches, a stage on the beach opposite the Brighton Metropole Hotel, near the West Pier,29 would have been within easy walking distance for Sickert from Walter Taylor’s house in Bedford Square.

Sickert’s interest in the spectacle of the pierrot theatre derived from his love of popular entertainment which earlier had found full expression in his series of London music hall scenes. The Highwaymen were by no means the only providers of entertainment in Brighton during the summer season in 1915. Despite the threat of closure to the attractions for the duration, the newspapers reported that large numbers of tourists flocked to the town in August to take advantage of the glorious summer weather. Visitors during the Bank Holiday weekend included some five thousand workers from the Woolwich Arsenal taking their first vacation since the outbreak of war.30 Many factory workers were taking home more money from their contribution to the war effort than they had ever enjoyed before and during their rare leisure hours were willing to spend their earnings at Brighton’s many diversions. Daily entertainments included West End plays and musicals at the Palace Pier, the West Pier and the Theatre Royal, classical concerts by the Municipal Orchestra in the Aquarium Winter Gardens and a variety show of singers, comedians and musicians at the Hippodrome. Other attractions during August 1915 included a flying visit from Stella Carol, the ‘Human Lark’, a showing of the film Brave Little Belgium Before and During the War, and a lecture by Hilaire Belloc on ‘The War: The Present Position and the Recent Fighting’ at Hove Town Hall. Similar acts to that offered by the Highwaymen were also available throughout the war, courtesy of the Palace Pier Follies and the West End Entertainers who performed their routine twice daily.31

A particular treat during the middle of August 1915 was an appearance at the West Pier theatre by the Follies, one of the most famous and successful groups of vaudeville artistes of the period. The Follies toured the country and as well as appearing in London they bore the distinction of having been invited to perform for the Royal Family. They offered a full and varied programme of humorous and picturesque songs, dancing in pierrot costumes, music hall burlesque, grand opera and a pageant of historical characters. As a professional troupe, the Follies’ standard of performance was very high, higher it must be supposed than that offered by Jack Sheppard’s troupe or other local pierrot companies performing on the Front. It was typical of Sickert’s idiosyncratic, low-brow tastes that he eschewed Brighton’s more sophisticated, glamorous entertainments in favour of something a little less polished. Just as he tended to patronise the smaller, cruder music halls in Camden Town instead of the lavish establishments of London’s West End, Sickert preferred the unrefined, low-key pleasures of the local pierrot theatre erected on the front at Brighton.

Pierrot

The character of Pierrot originated in the Italian Commedia dell’arte of the sixteenth century, but was adopted by French pantomime and developed into one of the most important and recognisable figures in alternative, low-brow theatre. In the Commedia dell’arte tradition, Pierrot is a romantic clown or buffoon who is hopelessly in love with shallow Columbine, and becomes an unwitting victim of the tricks of Harlequin. Essentially a comic figure provoking the audience to laughter, Pierrot simultaneously incites sympathy and pity with his hapless antics, lovelorn countenance and melancholic air. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries this dual role of the tragic comedian assumed a new visibility and intellectual resonance in modernist culture. The themes and motifs of the Commedia dell’arte were extremely influential to a number of modernist artists, writers and composers, who were drawn to its subversive nature and irreverent spirit.32 Themes and symbols drawn from the vulgar, improvisational world of the Commedia began to be taken up and absorbed into high culture, most famously in the magnificent costumes and characters of Sergei Diaghilev’s hugely influential Ballets Russes, for example in Diaghilev’s production of Carnaval by Robert Schumann which premiered in 1910. In the poetry of Jules Laforgue (1860–1887) and the paintings of Pablo Picasso (1881–1973) and Georges Rouault (1871–1958), the Pierrot was celebrated as the symbolic hero of sensibility, and adopted as representative of the role of the artist in society.33 The character embodied the ability to employ parody and humour in the face of tragedy and was identified with the artist’s struggle to come to terms with modern life.34

Sickert must have been well aware of the Commedia dell’arte tradition and its recent renaissance in contemporary culture. As a young man he had initially pursued a career on the stage and his love of theatre remained with him throughout his life. In 1903–4 he had painted Venetian Stage Scene 1903–4 (private collection),35 a small panel for which Tate’s drawing, Pierrot and Woman Embracing, is a preliminary sketch (Tate N05095). In 1911 the Ballets Russes had appeared in London to widespread critical acclaim and Sickert was friendly with a number of Diaghilev’s London supporters including the Sitwells and Lady Ottoline Morrell. Both the dramatic, romantic and masculine Venetian pierrot of Sickert’s earlier painting and Diaghilev’s ultra-modern aestheticism seem far removed from the cheery bonhomie and popular appeal of the typical seaside entertainer. Yet Sickert’s painting Brighton Pierrots demonstrates and engages with the power and pathos associated with the figure of the Pierrot. Sickert has deliberately created a complex and highly charged scene in which the pervasive mood is one of melancholy. This was identified by the art critic of the Daily Telegraph who on seeing the painting exhibited at the Carfax Gallery in 1916 wrote:

Here we have a company of players in more or less Italian comedy (commedia dell’arte) costumes, performing on a stage set up in the open, with a background of Brighton houses of the more old-fashioned type. The charm of the picture is in the conflict between the luminous air of evening and the artificial lights, under which these poor abraded butterflies of the stage appear half-immaterialised, and with a glamour that is theirs but for this short moment.36

In common with a painting like Minnie Cunningham 1892 (Tate T02039), Sickert has employed an oblique angle and a cropped composition derived from Edgar Degas with which to explore the disorientating, ambiguous effects of costumes, artificial lighting and the contrived atmosphere of theatrical performance. Possible compositional precedents for the highly unusual side view are biblical ‘Ecce Homo’ subjects in which artists such as Rembrandt (1606–1669, Ecce Homo 1634, National Gallery, London) and Honoré Daumier (1808–1879, Ecce Homo c.1849–52, Museum Folkwang, Essen) show Christ in profile being presented to the crowd by Pontius Pilate. Brighton Pierrots shares with these paintings a sense of unease and the tragic display of a victim of suffering. Sickert’s bizarre arrangement of the figures undermines their perceived joviality, particularly the disjointed body of the Pierrot behind the pillar with his kicking legs seen as if bizarrely amputated from his body. This dislocation, combined with Sickert’s acidic colouring and dramatically shaped shadows, contribute to a disquieting sense of all not being well. Despite their comic, brightly coloured costumes the Pierrots seem desultory and lack-lustre and the foremost performer gazes out onto a depleted audience.

Brighton and the First World War

The subdued, transient pleasures portrayed in Brighton Pierrots reflect the prevalent widespread anxiety of wartime England. A pencil sketch of the audience (fig.3), presumably executed on the spot, reveals a larger crowd of people watching the show. This suggests that Sickert has deliberately exaggerated an idea of absence in his painting. The empty row of deckchairs serves as a reminder of the impact of the war, invoking a sense of loss and sacrifice. Although the newspapers reported an upbeat mood in Brighton and significant numbers of visiting tourists, evidence of the conflict was a constant and unavoidable presence throughout the town. The casualty lists recording heavy losses from the Front were printed every week in the Brighton Gazette. The use of the Brighton Pavilion as a hospital for wounded Indian soldiers afforded the town’s inhabitants the ‘strange spectacle of Red Cross vans occupied by parties of wounded Indians in loose blue robes and white turbans, and here and there a badly wounded soldier from the East being wheeled along the promenades in a hospital chair by a British orderly’.37 Performances at the Palace Pier commenced each night at 6.30 pm instead of 7 pm because of restrictions imposed on lighting. The fear of bombing raids necessitated the shading of lights an hour after sunset, which during August was at about 8.15 pm. On clear nights, the sound of the guns in Flanders could even be heard from across the Channel. Sickert recalls the tradition of the Pierrot as a symbol for comedy in the face of tragedy and reinvents that role within a contemporary setting. The seaside pierrots represent a poignantly brave, but rather pathetic effort to inspire laughter at a time when the general populous was experiencing fear on an unprecedented scale.

The painting also echoes Sickert’s own dejected spirits and his particular fears for the fate of Dieppe. He revealed his concerns about the proximity of the fighting in a letter to Ethel Sands:

My constant personal terror is for my dear Dieppe. I had a charming note from [Edward] Marsh saying “Winston [Churchill] would think over” what I have said. But a small force of marines would of course be cut up & be worse than useless ... My days of [torment?] at Dieppe, quite unselfish, when I examine myself, it is of the mayor of Dieppe (a bric-a-brac dealer I have known 30 years) the British Consul, an old salt who will stick to his guns, all the shop-men & all the market-women, all the youths & the old men whom I love that I am thinking day & night. It hurt me to leave them so. 38

He himself, at the age of fifty-five, felt personally oppressed and stifled by the war, writing ‘What a stupid year 1915 will have been. One goes on in a kind of constipated dream’, and in another letter, ‘This war constipates my heart & my pen’.39 However, the effect of the conflict on his painting ‘seems to have condensed my talent like pressure of air or water does at atmosphere’.40 Brighton Pierrots can be seen as a creative release and expression of wartime tensions. In this it is comparable to Merry-Go-Round 1916 (Tate T03846) by Mark Gertler (1891–1939). Gertler’s painting uses the image of people screaming on a fairground carousel as a bitter comment on the relentless mechanistic horror of the First World War.41 Sickert takes up another popular entertainment and makes the imagined sounds of stage jollity an ironic recreation of lost pleasure and well-being. The only woman on the stage, the pierrette pianist, is placed at the vanishing point of the painting’s perspective and turns to stare at the viewer, as if complicit in the artist’s exposure of the theatrical and artistic deception.

Nicola Moorby

February 2004

Notes

Wendy Baron, Perfect Moderns: A History of the Camden Town Group, Aldershot and Vermont 2000, p.134.

Walter Sickert, letter to Ethel Sands, not dated [August/September 1915], Tate Archive TGA 9125/5, no.93.

Walter Sickert, letter to Ethel Sands, not dated [August/September 1915], Tate Archive TGA 9125/5, no.93.

Stephen Hackney, Rica Jones, Joyce Townsend (eds.), Paint and Purpose: A Study of Technique in British Art, London 1999, p.125.

Wendy Baron and Richard Shone (eds.), Sickert: Paintings, exhibition catalogue, Royal Academy, London 1992, p.252.

Janice Anderson and Edmund Swinglehurst, The Victorian and Edwardian Seaside, London and New York 1978, p.111.

Bill Pertwee, Pertwee’s Promenades and Pierrots: One Hundred Years of Seaside Entertainment, Newton Abbot 1979, pp.12–14.

Judy Middleton, Brighton and Hove Volume 1: A Portrait in Old Picture Postcards, Market Drayton 1991, p.36.

Martin Green and John Swan, The Triumph of Pierrot: The Commedia dell’Arte and the Modern Imagination, New York 1986, p.1.

Related biographies

Related essays

Related catalogue entries

Related audio

-

Mark Sheridan 1864–1918 performs 'I do like to be beside the Seaside' recorded October 1909© Windyridge Music Hall CDs

-

Olly Oakley 1877–1943 performs 'Jessamine' recorded January 1907© Windyridge Music Hall CDs

How to cite

Nicola Moorby, ‘Brighton Pierrots 1915 by Walter Richard Sickert’, catalogue entry, February 2004, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www