Henry Moore OM, CH Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944-5

Image 1 of 12

-

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944-5© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944-5© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944-5© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944-5© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944-5© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944-5© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944-5© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944-5© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944-5© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944-5© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944-5© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944-5© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944-5© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944-5© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944-5© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944-5© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944-5© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944-5© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944-5© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944-5© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944-5© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944-5© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944-5© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944-5© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH,

Maquette for Madonna and Child

1943, cast 1944-5

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

This small bronze sculpture is one of twelve maquettes for a Madonna and Child that Henry Moore was commissioned to make in 1943 for St Matthew’s Church in Northampton. This particular design, which was made originally in clay, was not the one selected to be scaled up for the final sculpture, but it was later cast in bronze along with five of the other maquettes.

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Maquette for Madonna and Child

1943, cast 1944–5

Bronze

140 x 75 x 75 mm

Inscribed ‘Moore’ on side of seat

Purchased from the artist through the Berkeley Galleries (Knapping Fund) 1945

In an unnumbered edition prior to an edition of 7 plus 1 artist’s copy

N05600

Maquette for Madonna and Child

1943, cast 1944–5

Bronze

140 x 75 x 75 mm

Inscribed ‘Moore’ on side of seat

Purchased from the artist through the Berkeley Galleries (Knapping Fund) 1945

In an unnumbered edition prior to an edition of 7 plus 1 artist’s copy

N05600

Ownership history

Purchased from the artist through the Berkeley Galleries (Knapping Fund) in 1945.

Exhibition history

1945

Henry Moore: Drawings and Sculptures, Berkeley Galleries, March 1945–April 1945, no.2 or 4.

1948

Sculpture and Drawings by Henry Moore, British Pavilion, Venice Biennale, Venice, June–September 1948, no.27a.

1966

Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings, Israel Museum, Jerusalem, September–October 1966; Tel-Aviv Museum, Tel Aviv, November–December 1966, no.33a.

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery, London, June–August 1978, no number.

1981

Henry Moore: Sculptures, Drawings, Graphics 1921–1981, Palacio de Velázquez, Palacio de Cristal, Parque de El Retiro, Madrid, May–August 1981, no.187.

1981

Henry Moore, Fundacao Calouste Gulbenkian, Lisbon, September–November 1981, no.160.

1982

Henry Moore en México: Escultura, Dibujo, Grafica de 1921 a 1982, Museo de Arte Moderno, Mexico City, November 1982–January 1983, no.127.

1990

Henry Moore: Sketch-Models and Working-Models, South Bank Centre, London, May–June 1990, no.4.

1992

Henry Moore 1898–1986, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, April–July 1992, no.70.

1995

Henry Moore: A Retrospective, BWA Gallery, Krakow, March–May 1995, no.55.

2000

Moore in China, China Art Gallery, Beijing, October–November 2000, no.15.

2005

Henry Moore y México, Museo Dolores Olmedo, Mexico City, June–October 2005, no.31.

References

1944

Geoffrey Grigson and Eric Newton, ‘Henry Moore’s Madonna and Child’, Architectural Review, vol.95, no.569, May 1944, pp.137–40.

1944

Walter Hussey, ‘Correspondence [Letter to the Editor]’, Architectural Review, vol.96, no.570, July 1944, p.1.

1944

Herbert Read (ed.), Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings, London 1944, reproduced pl.107b.

1944

Sir Kenneth Clark, ‘A Madonna by Henry Moore’, Magazine of Art, vol.37, no.7, November 1944, pp.247–49.

1945

Nikolaus Pevsner, ‘Thoughts on Henry Moore’, Burlington Magazine, vol.86, no.503, February 1945, pp.47–9.

1945

Philip Hendy, ‘Art – Henry Moore’, Britain Today, no.106, pp.34–5.

1946

Nikolaus Pevsner, ‘Henry Moore’s Madonna’, Student Movement, October 1946, pp.4–5.

1946

Mary Sorrell, ‘Henry Moore’, Apollo, vol.44, November 1946, pp.116–18.

1946

James Johnson Sweeney, Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Museum of Modern Art, New York 1946, reproduced pl.74.

1948

Sculpture and Drawings by Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, British Pavilion, Venice Biennale, Venice 1948.

1949

Walter Hussey, ‘A Churchman Discusses Art in the Church’, Studio, vol.138, no.678, September 1949, pp.80–1, 95.

1954

Lawrence Alloway, ‘The Siting of Sculpture’, Listener, 17 June 1954, pp.1044–6.

1960

Will Grohmann, The Art of Henry Moore, London 1960, pp.137–9.

1965

Herbert Read, Henry Moore: A Study of his Life and Work, London 1965, pp.151–7.

1966

Henry Moore: Sculptures and Drawings, exhibition catalogue, Israel Museum, Jerusalem 1966, reproduced no.33a.

1966

Donald Hall, Henry Moore: The Life and Work of a Great Sculptor, London 1966, pp.101–17.

1967

Henry Moore: One Yorkshireman Looks at His World, dir. by John Read, television programme, broadcast BBC2, 11 November 1967, http://www.bbc.co.uk/archive/henrymoore/8807.shtml, accessed 7 February 2014.

1968

John Russell, Henry Moore, London 1968, pp.90–9.

1968

John Hedgecoe (ed.), Henry Moore, London 1968.

1973

John Russell, Henry Moore, 1968, revised edn, London 1973, pp.119–23.

1975

Kenneth Clark, ‘Dean Walter Hussey: A Tribute to His Patronage of the Arts’, in Chichester Nine Hundred, Chichester 1975, pp.68–72.

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1978, reproduced p.23.

1978

80/80, exhibition catalogue, Thomas Gibson Fine Art, London 1978 (another cast reproduced p.15).

1979

John Read, Portrait of an Artist: Henry Moore, London 1979.

1981

Sandy Nairne and Nicholas Serota (eds.), British Sculpture in the Twentieth Century, exhibition catalogue, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London 1981, p.146.

1981

Henry Moore: Sculptures, Drawings, Graphics 1921–1981, exhibition catalogue, Palacio de Velázquez, Madrid 1981, reproduced no.159.

1982

Henry Moore en México: Escultura, Dibujo, Grafica de 1921 a 1982, exhibition catalogue, Museo de Arte Moderno, Mexico City 1982, no.127.

1985

Walter Hussey, Patron of Art: The Revival of a Great Tradition among Modern Artists, London 1985.

1988

David Sylvester (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 1: Complete Sculpture 1921–48, 1957, 5th edn, London 1988.

1988

Susan Compton (ed.), Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Royal Academy of Arts, London 1988, pp.222–3.

1990

Henry Moore: Sketch-Models and Working-Models, exhibition catalogue, South Bank Centre, London 1990, reproduced p.32.

1992

Henry Moore 1898–1986, exhibition catalogue, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney 1992, reproduced p.95.

1993

Images of Christ: Religious Iconography in Twentieth Century British Art, exhibition catalogue, Northampton Museum and Art Gallery, Northampton 1993.

1992

Garth Turner, ‘Aesthete, Impressario and Indomitable Persuader: Walter Hussey at St Matthew’s, Northampton, and Chichester Cathedral’, in Diana Wood (ed.), The Church and the Arts, Oxford 1992, pp.523–35.

1995

Henry Moore: A Retrospective, exhibition catalogue, BWA Gallery, Krakow 1995, reproduced no.55.

2000

Moore in China, exhibition catalogue, China Art Gallery, Beijing 2000 (another cast reproduced p.15).

2003

Roger Berthoud, The Life of Henry Moore, 1987, revised edn, London 2003.

2005

Henry Moore y México, exhibition catalogue, Museo Dolores Olmedo, Mexico City 2005, reproduced p.61.

2006

David Mitchinson (ed.), Celebrating Moore: Works from the Collection of the Henry Moore Foundation, London 2006 (another cast reproduced p.207).

Technique and condition

This single-part bronze maquette depicts a mother seated on a bench holding a child on her leg, who looks into his mother’s eyes. The flat area of ground underneath the bench forms the base of the sculpture.

The bronze is a solid cast with no hollow cavity. Moore made an original model in clay from which the foundry took a mould to cast the final version. Moore was able to indicate facial features, fingers and drapery in the clothing by impressing marks into the clay, which is a soft, malleable material. The level of surface detail in the bronze cast suggests that it was made using the traditional lost wax technique. Although it is possible to see where casting flashes have been filed away and chased to blend with the whole, there is otherwise little post-cast finishing.

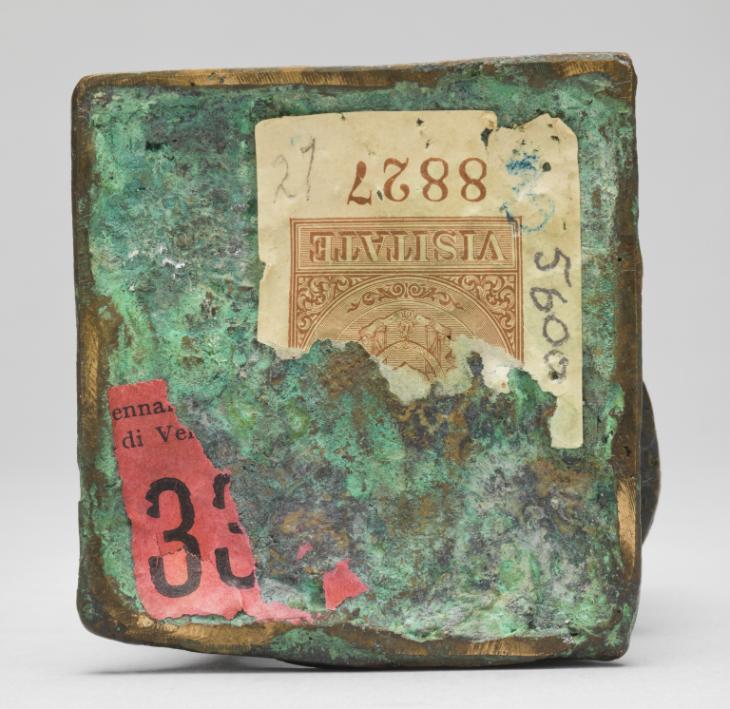

Detail of patina on Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944–5

Tate N05600

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

Detail of patina on Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944–5

Tate N05600

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of signature on Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944–5

Tate N05600

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Detail of signature on Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944–5

Tate N05600

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The bronze surface has been coloured using chemical patination techniques, first with a slightly transparent brown colour, which was applied over the entire surface, and then with a more opaque green colour, which has been rubbed back with a light abrasive on the high points of the sculpture to pick out the details of the form (fig.1). The patina was then finished with a coating of wax. The brown base colour is often used on bronzes and is likely to have been applied using a solution of potassium polysulphide (otherwise known as ‘liver of sulphur’) in water. There are many different patina recipes used to produce green colours on bronzes but they often contain mixtures of copper and ammonium salts.

The signature ‘MOORE’ was inscribed on the lower part of the bench (fig.2) to the figure’s right using a sharp point either into the clay model or the pre-cast wax. Although the surface of the sculpture looks as if it may have been handled often, it is generally in good condition and has not required treatment.

Lyndsey Morgan

March 2011

How to cite

Lyndsey Morgan, 'Technique and Condition', March 2011, in Robert Sutton, ‘Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944–5 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, December 2012, revised by Alice Correia, March 2014, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://wwwEntry

Henry Moore

Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944–5

Tate N05600

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

Henry Moore

Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944–5

Tate N05600

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of Madonna's face in Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944–5

Tate N05600

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Detail of Madonna's face in Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944–5

Tate N05600

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Maquette for Madonna and Child is a small bronze sculpture cast from an original study modelled in clay. It depicts a woman sitting on a low bench cradling a child, who is seated upright on her left leg (fig.1). The woman’s arms support the child’s legs and back while the child holds itself away from her broad torso. The woman wears a shorter than knee-length dress into which lines denoting drapery have been incised on the upper right arm and across her lap, while her fingers and her hair, which falls leadenly over her right shoulder, have been simply but deliberately modelled. Both the woman’s and the child’s animated expressions have been picked out with delicate, abbreviated incisions, with the result that they seem to look towards and yet past one another (fig.2). Despite these abbreviations, the critic John Russell suggested that in his figurative sculpture Moore was able to create ‘portraits’ without depicting a specific person by allowing ‘the body to define the character of his figures’.1

Henry Moore

Madonna and Child 1943–4

Hornton Stone

Church of St Matthew, Northampton

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.3

Henry Moore

Madonna and Child 1943–4

Church of St Matthew, Northampton

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

The commission

The commission came about after the vicar of St Matthew’s, the Reverend Walter Hussey, saw a number of Moore’s Shelter Drawings in an exhibition at the National Gallery, London, in the autumn of 1942. The exhibition had been organised by the War Artists’ Advisory Committee (WAAC), a governmental body set up under the auspices of the Ministry of Information to boost British morale during wartime by commissioning images of British endurance from recognised artists. Having been forced to give up sculpture due to a lack of available materials, Moore had produced a series of drawings of women and children sheltering in the London Underground during the Blitz, which he showed to Kenneth Clark, Director of the National Gallery and Chairman of the WAAC, who invited him to become an Official War Artist.

Although some visitors to the National Gallery found that Moore’s Shelter Drawings did not accurately convey the reality of their wartime experiences, on his return to Northampton Hussey signalled his admiration for the work to Harold Williamson, Director of the Chelsea School of Art, which had been relocated to Northampton in 1941 to escape the bombing in London.2 As Hussey recalled in his memoirs, ‘I remember shaking my finger at him and saying: “That is the sort of man who ought to be working for the Church – his work has the dignity and force that is desperately needed today”’.3 Moore had taught sculpture at the Chelsea School of Art since 1933 and so was well known to Williamson, who arranged for the two to meet the following week when Moore was visiting Northampton. It was then that Hussey proposed the commission to Moore: ‘I asked him whether he thought he would be interested in the project; he replied that he would, though whether it could go further, whether he could and would want to do it, he just couldn’t say at present’. Hussey also asked Moore if he felt able to believe in the commission, to which the artist responded ‘Yes, I would. Though whether or not I should agree with your theology, I just do not know. I think it is only through our art that we artists can come to understand your theology’.4 Moore’s attitude to Christianity was ambivalent; he stated in 1973 that ‘although I was baptised and made to go to church as a boy, I am not a practicing Christian’.5

In early December 1942 Hussey wrote to Moore enquiring whether he had considered the scheme any further. Hussey was at pains to express his desire for Moore to undertake the commission while also respecting the sensibilities of both the artist and the congregation of St Matthew’s. A sculpture that offended the ‘religious susceptibilities’ of the congregation was to be avoided, but he was also anxious that Moore should not have to compromise his artistic integrity.6 Moore replied on 6 March 1943, stating, ‘I’ve not forgotten the scheme and I’m very keen to begin thinking seriously about it and I think that in a couple of weeks’ time I shall get the chance to begin playing about making note-book sketches to get ideas for it’.7 On 29 April Moore wrote to Hussey confirming that he had at last ‘begun notebook sketches for it’.8

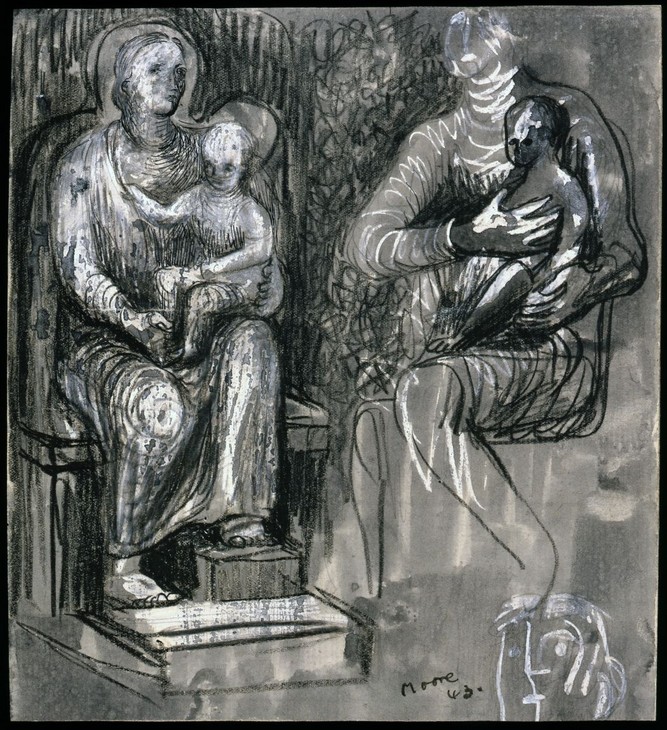

Henry Moore

Madonna and Child Studies 1943

Graphite, wax crayon, coloured crayon, watercolour wash, pen and ink on paper

191 x 175 mm

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Henry Moore

Madonna and Child Studies 1943

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Women and Children in the Tube 1940

Graphite, wax crayon, watercolour wash, pen and ink on paper

280 x 380 mm

Imperial War Museum, London

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.5

Henry Moore

Women and Children in the Tube 1940

Imperial War Museum, London

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Between April and June 1943 Moore created what is now identified as the Madonna and Child Sketchbook, and it is from these sketches that he modelled twelve clay maquettes between June and July. Each of the three-dimensional maquettes appear to have been drawn to varying extents.9 Among the sketches Moore produced at this time, the closest immediate precedent for this Maquette for Madonna and Child can be found on the right-hand side of a single page on which two representations of the Madonna and Child were sketched (fig.4). This hurriedly drawn and seemingly incomplete depiction of the Madonna appears to present an ordinary woman in an everyday pose in contrast to the instantly recognisable Madonna and Child on the left of the page, which relates more closely to idealised images of the Virgin and Child. The mother on the right wears an above knee-length dress, and the awkward angle of her lower legs and the familiarity of her maternal posture not only anticipate the sculpture but also appear comparable to that of the central figure in one of Moore’s shelter drawings produced three years earlier, entitled Women and Children in the Tube (fig.5). In this drawing the short sleeves and skirt of the mother’s dress are clearly defined, a motif that Moore would employ on this and another of the clay maquettes. Considered together with these drawings, it seems that Moore created this sculpture as part of an exploratory process. This may explain why the art historian Will Grohmann wrote in 1960 that the earliest of the maquettes Moore produced were still ‘no more than a mother and child’.10 It could be that at the time of the commission Moore was still engaged with the imagery of war that had inspired his Shelter Drawings. By contrasting more traditional representations of the Madonna and Child with non-idealised depictions of the theme, as in the drawing Madonna and Child Studies, Moore perhaps sought to reconcile these differences.

Henry Moore

Mother and Child 1932

Green Hornton stone

Sainsbury Centre for Visual Art, Norwich

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.6

Henry Moore

Mother and Child 1932

Sainsbury Centre for Visual Art, Norwich

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

I began thinking of the ‘Madonna and Child’ for St Matthew’s by considering in what ways a Madonna and Child differs from a carving of just a ‘Mother and Child’ – that is by considering how in my opinion religious art differs from secular art. It’s not easy to describe in words what this difference is, except by saying in general terms that the ‘Madonna and Child’ should have an austerity and a nobility and some touch of grandeur (even hieratic aloofness), which is missing in the ‘everyday’ Mother and Child idea.13

To create his Mother and Child sculpture in 1932 Moore had used the technique of direct carving, which involved working directly on the stone without reference to a model or preparatory sketches. In the early 1930s Moore and other contemporary sculptors, including Barbara Hepworth and John Skeaping, believed that by working directly on the stone, and in response to its particular physical properties, a sculptor could create a work of art that had more authenticity than one that eschewed the true qualities of its material. Moore later recalled that he ‘liked the different mental approach involved’ in direct carving, ‘that you begin with the block and have to find the sculpture that’s inside it’.14 By making small clay maquettes of the Madonna and Child prior to making the full-size stone carving, Moore therefore departed from this pre-war working method.

Photograph of six terracotta maquettes for Madonna and Child 1943

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore

Fig.7

Photograph of six terracotta maquettes for Madonna and Child 1943

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore

I was able to begin 4 or 5 days ago, translating some of the small note-book drawings I’d made, into small clay models and I’ve now got 4 clay models (each about 4” high) on the go. I don’t know yet what I think of these, and shan’t until each one has had a few more hours spent on it. But anyhow there are 4 or 5 small drawings in the note-book which I want to try out in solid forms in clay too, so it’s going to be another 2 or 3 weeks, I’m afraid.17

When seen together, the maquettes reveal how Moore experimented with the position and size of the Christ child and the pose of the Madonna, and testify to Moore’s growing interest in drapery. Moore later acknowledged that the folds of the mother’s dress in the maquettes were directly informed by his Shelter Drawings: ‘I had never used drapery in sculpture prior to making the shelter drawings. Then I saw sculptural form in the folds of the material and employed it’.18 The fact that Moore knew where the final sculpture was to be positioned in St Matthew’s Church also informed how he modelled the figures. The allocated site was against a wall, and as such Moore paid little attention to the backs of his maquettes. In his discussion of the commission, the art critic Herbert Read noted that the final sculpture had to confirm to what he called ‘the law of frontality’, by which Moore had to convey mass and volume without ‘an all round perambulation’.19

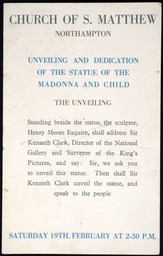

Of the twelve maquettes produced in clay five were selected by Moore to show to Hussey on 23 July 1943. This maquette was one of the five selected, and although it was not Moore’s preferred design for the final sculpture, he informed Hussey that he would ‘be prepared to base the finished statue’ on any one of the five.20 The production of multiple models provided Hussey not only with an element of choice but also a clearer idea of what the finished work might look like. Kenneth Clark, who had viewed Moore’s models with Hussey on 23 July wrote, ‘as you will have seen from the models which he showed you ... [Moore] has thought out the problem of the Madonna and Child most seriously, and his sketches promise that this will be one of his finest works’.21 After viewing the five proposed maquettes in London, Hussey took them back to Northampton to show members of St Matthew’s Parochial Church Council, who selected the sculpture to be commissioned. This Maquette for Madonna and Child was not chosen as the design for the final sculpture, which Moore carved throughout the latter half of 1943 and early 1944, and which was dedicated in St Matthew’s Church on Saturday 19 February 1944.

In Moore’s catalogue raisonné the clay studies for Madonna and Child are described as being made in terracotta.22 In 1963 Moore addressed any misunderstanding, explaining that ‘the original maquettes of the MADONNA AND CHILD ... sculptures were all modelled direct in clay and then baked, and so became terra-cottas. It was from these terra-cottas that the small bronzes were cast’.23 Moore’s catalogue raisonné indicates that six of Moore’s preliminary terracotta maquettes were cast in bronze editions. This Maquette for Madonna and Child was cast at the Art Bronze Foundry in London. Casting notes for the owner of the foundry, dated simply ‘March 28’, identify five Madonna and Child maquettes for casting, along with three maquettes for Moore’s Family Group, which date from 1944–5.24 The inclusion of Maquette for Family Group 1945 (Tate N05606) as the seventh sculpture on this list suggests that Moore made these casting notes in 1945. This Maquette for Madonna and Child is numbered two on the list and a small sketch of the sculpture is annotated with the phrase ‘one with broken neck’ suggesting that the Madonna’s neck had been damaged. The notes also indicate that two bronze examples of this particular maquette were cast and delivered to an unnamed gallery. It is likely that the gallery mentioned on the note was the Berkeley Galleries, London, where an example of this Maquette for Madonna and Child was exhibited in March–April 1945, and from which Tate acquired its cast. There is some uncertainty as to whether the unnumbered bronze maquettes were cast in editions of five or seven due to discrepancies between the foundry paperwork and Moore’s catalogue records held at the Henry Moore Foundation.25 It was not until some years after the Second World War that Moore began to efficiently maintain his financial and business paperwork, and it is known that in 1955 Moore cast this sculpture in an edition of seven plus one artist’s copy at Galizia Foundry in London.

In an article published in the Burlington Magazine in July 1948, Sylvester, who had worked as Moore’s personal assistant in 1945, noted that ‘Moore had always made maquettes for his larger sculptures, but it was not until he cast about half-a-dozen of the ten or so clay studies for the Northampton Madonna that he began to make bronzes of them’.26 The bronzes were produced to be sold privately, and probably helped off-set the cost of the commission. As bronze casts, these sculptures can be considered as stand alone works rather than as preparatory models for the larger sculpture. This commission thus represented a turning point in Moore’s career, as he moved away from the ethos of direct carving, which had preoccupied him during the 1920s and 1930s, towards a long and sustained experimentation with bronze. Moore’s turn to making multiple bronze casts drastically altered the type of work he was able to produce, and provided more opportunities to sell his work.

Moore and the Tate collection

This maquette was one of four bronze studies for the Northampton Madonna and Child bought by Tate in 1945 (Tate N05600–N05603), and they were some of the earliest works by Moore to be purchased for the Tate collection. Their purchase illustrated the desire of the director Sir John Rothenstein to represent Moore’s work in the collection. In contrast, Rothenstein’s predecessor, J.B. Manson, had previously told the Tate trustee Robert Sainsbury ‘over my dead body will Henry Moore ever enter the Tate’.27 Rothenstein’s appointment thus signalled a shift in the direction of Tate’s ambitions. One of his first actions as director had been to accept the donation from the Contemporary Art Society of Moore’s Recumbent Figure 1938 (Tate N05387). Then in 1941 Rothenstein encouraged the appointment of Moore to Tate’s Board of Trustees.

In mid-1944 Rothenstein wrote to Moore asking whether Tate could commission another full-size Madonna and Child based on the existing maquettes. Moore politely turned down the suggestion, writing ‘its now more than a year since these little figure studies were done, + that’s whats [sic] making me hesitate now over your suggestion – for it would mean putting my mind back in working to a year ago’.28 Instead, Moore suggested that the Tate might be interested in some of the studies for a ‘Family Group’ he had recently begun working on, a full-size bronze version of which was bought by the Tate in 1950. The immediate result was that Tate bought four maquettes for the Madonna and Child and three maquettes for the Family Group. Three of the Madonna and Child maquettes were bought at the relatively affordable price of twenty-five guineas each, while the maquette from which the final full-size version had been scaled up (Tate N05602) cost thirty guineas.29

The four maquettes for Madonna and Child were purchased from the artist through the Berkeley Galleries in early 1945 with money from the Knapping Fund.30 The Knapping Fund was the residuary estate of Miss Helen Knapping bequeathed to the Trustees of the National Gallery in 1935 to be spent on work by living or recently deceased British artists. A fraction of this money was allocated to the Tate by the National Gallery, as Tate’s purchasing power continued to rely on charitable donations and private patronage until well after the Second World War.

Another example of this Maquette for Madonna and Child is held in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, and the Henry Moore Foundation holds the other 1945 example that was cast by the Art Bronze Foundry. Other casts are believed to be in private collections. An example with a bright green patina was sold at Christie’s auction house in New York in 1997.31 The terracotta original remains in the collection of Moore’s daughter, Mary Moore.

Robert Sutton

December 2012

Revised by Alice Correia

March 2014

Notes

Walter Hussey, Patron of Art: The Revival of a Great Tradition among Modern Artists, London 1985, p.23.

Henry Moore cited in Donald Carroll, The Donald Carroll Interviews, London 1973, p.35, reprinted in Alan Wilkinson (ed.), Henry Moore: Writings and Conversations, Aldershot 2002, p.269.

The pages from the sketchbook are reproduced in Ann Garrould (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 3: Complete Drawings 1940–49, Aldershot 2001, pp.190–5.

David Sylvester, ‘The Evolution of Henry Moore’s Sculpture II’, Burlington Magazine, vol.90, no.544, July 1948, p.190.

See John and Véra Russell, ‘Conversations with Henry Moore’, Sunday Times, 17 December 1961, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, pp.47, 230.

Moore photographed these terracotta maquettes in various groupings prior to their casting. Fig.7 illustrates six of the twelve models and were reproduced in Herbert Read (ed.), Henry Moore: Sculptures and Drawings, London 1944. This book would become the basis for the first volume of Moore’s catalogue raisonné, in which the same two photographs have been reproduced ever since. See David Sylvester (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 1: Complete Sculpture 1921–48, 1957, 5th edn, London 1988, p.138.

A.D.B. Sylvester, ‘The Evolution of Henry Moore’s Sculpture: I’, Burlington Magazine, vol.90, no.543, June 1948, p.158.

Henry Moore, letter to Martin Butlin, 22 January 1963, Tate Artist Catalogue File, Henry Moore, A23941.

See Ann Garrould (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 3: Complete Drawings 1940–49, Much Hadham 2001, p.195, no.43.105.

Roger Berthoud, The Life of Henry Moore, 1987, revised edn, London 2003, p.183. Manson’s remark was cited by Sainsbury during an interview undertaken by Berthoud in May 1983.

Related essays

- Myriad Mediations: Henry Moore and his Works on Screen 1937–83 John Wyver

- Fashioning a Post-War Reputation: Henry Moore as a Civic Sculptor c.1943–58 Andrew Stephenson

- At the Heart of the Establishment: Henry Moore as Trustee Julia Kelly

- Henry Moore's Approach to Bronze Lyndsey Morgan and Rozemarijn van der Molen

- ‘Worthy of the great tradition’: Kenneth Clark on Henry Moore Chris Stephens

Related catalogue entries

Related material

-

Programme for the unveiling and dedication of the statue ... 19 February 1944Programme

Related reviews and articles

- Philip Hendy, ‘Art – Henry Moore’ Britain Today, no.106, 1945.

Related bibliography

How to cite

Robert Sutton, ‘Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944–5 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, December 2012, revised by Alice Correia, March 2014, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www