Henry Moore OM, CH Reclining Figure 1951

Image 1 of 15

-

Henry Moore OM, CH, Reclining Figure 1951© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Reclining Figure 1951© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Reclining Figure 1951© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Reclining Figure 1951© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Reclining Figure 1951© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Reclining Figure 1951© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Reclining Figure 1951© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Reclining Figure 1951© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Reclining Figure 1951© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Reclining Figure 1951© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Reclining Figure 1951© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Reclining Figure 1951© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Reclining Figure 1951© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Reclining Figure 1951© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Reclining Figure 1951© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Reclining Figure 1951© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Reclining Figure 1951© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Reclining Figure 1951© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Reclining Figure 1951© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Reclining Figure 1951© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Reclining Figure 1951© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Reclining Figure 1951© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Reclining Figure 1951© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Reclining Figure 1951© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Reclining Figure 1951© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Reclining Figure 1951© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Reclining Figure 1951© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Reclining Figure 1951© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Reclining Figure 1951© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Reclining Figure 1951© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH,

Reclining Figure

1951

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

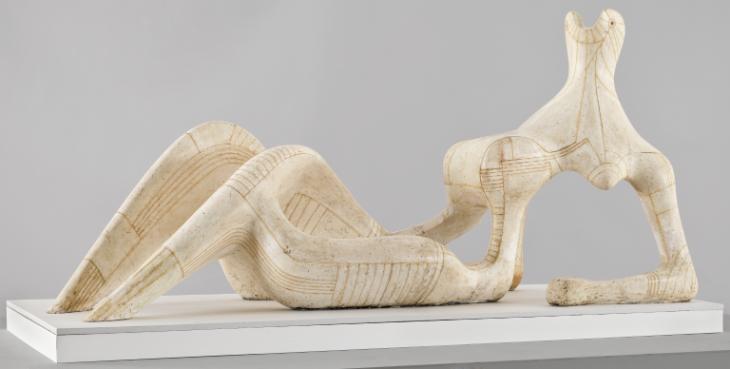

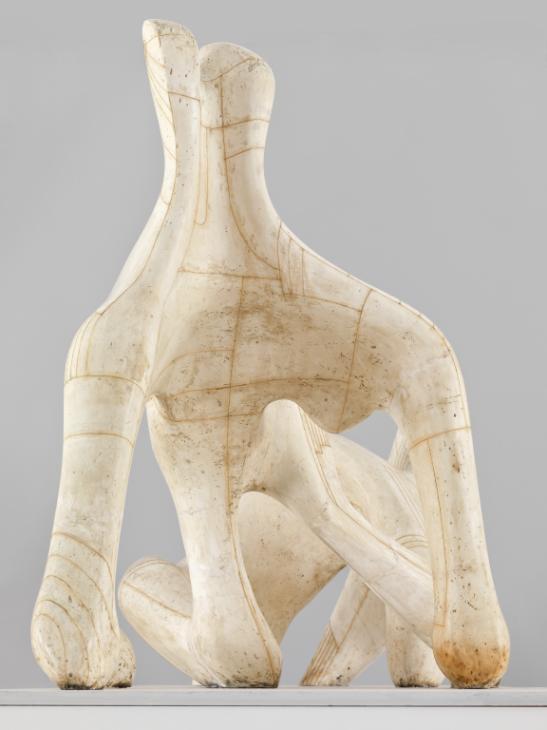

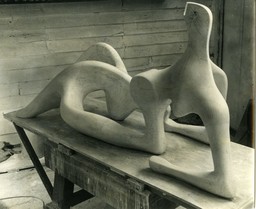

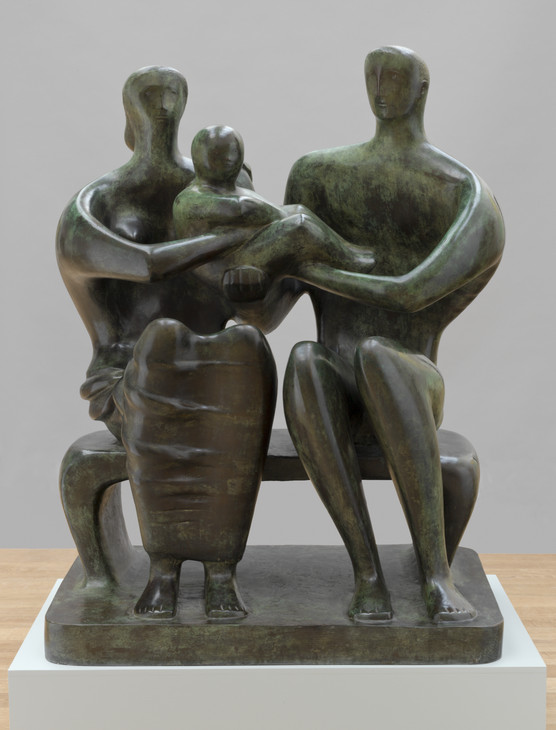

Reclining Figure is the original plaster sculpture from which a bronze cast was made for the Festival of Britain in 1951. The making of the piece was recorded in a pioneering documentary on Moore made by John Read for the BBC that year. The plaster sculpture remained in Moore’s possession until 1978 when it was included in the artist’s gift of thirty-six sculptures to the Tate Gallery.

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Reclining Figure

1951

Plaster and string on a wood base

1054 x 2273 x 892 mm

Presented by the artist 1978

T02270

Reclining Figure

1951

Plaster and string on a wood base

1054 x 2273 x 892 mm

Presented by the artist 1978

T02270

Ownership history

Presented by the artist to Tate in 1978 as part of the Henry Moore Gift.

Exhibition history

1960–1

Henry Moore: An Exhibition of Sculpture from 1950–1960, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London, November 1960–January 1961, no.3.

1977

Henry Moore: Sculptures et dessins, Musée de l’Orangerie des Tuileries, Paris, May–August 1977, no.60.

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery, London, June–August 1978, no number.

1988

Henry Moore, Royal Academy of Arts, London, September–December 1988, no.121.

2010

Henry Moore, Tate Britain, London, February–August 2010; Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, October 2010–February 2011; Leeds Art Gallery, Leeds, March–June 2011, no.129.

References

1951

Henry Moore, dir. John Read, television programme, broadcast BBC, 30 April 1951, http://www.bbc.co.uk/archive/henrymoore/8801.shtml, accessed 13 January 2014.

1951

David Sylvester (ed.), Sculpture and Drawings by Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1951, pp.14–15.

1951

Eric Newton, ‘Art and the Festival of Britain’, Queen, 25 April 1951 (Tate Archive TGA 8015–8.

1951

Eric Newton, ‘What Do The Public Think?: Henry Moore’s New Work at the Festival’, Art Fortnightly, 11 May 1951 (Henry Moore Foundation Archive).

1951

David Sylvester, ‘Festival Sculpture’, Studio, September 1951, pp.72–7 (bronze reproduced p.73).

1952

Hugh Casson, ‘South Bank Sculpture’, Image, no.7, Spring 1952, pp.48–60.

1952

Ernest I. Musgrave, ‘Editorial: The Reclining Figure’, Leeds Arts Calendar, no.17, Winter 1952, pp.1–3, 5, reproduced on front cover.

1959

Erich Neumann, The Archetypal World of Henry Moore, London 1959, pp.108–9.

1960

Henry Moore: An Exhibition of Sculpture from 1950–1960, exhibition catalogue, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London 1960 (bronze reproduced no.3).

1960

Will Grohmann, The Art of Henry Moore, London 1960, p.53.

1966

Philip James (ed.), Henry Moore on Sculpture, London 1966, pp.101, 118 (bronze reproduced pls.37–8).

1968

David Sylvester, Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1968, p.53.

1968

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Museum Boymans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam 1968 (plaster in progress reproduced).

1968

John Hedgecoe (ed.), Henry Moore, London 1968, pp.188, 197, 263.

1968

John Russell, Henry Moore, London 1968, pp.125–7.

1970

Robert Melville, Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings 1921–1969, London 1970, p.167.

1975

John Russell, Henry Moore, London 1975, p.148 (bronze version reproduced, pl.73).

1976

Mary Banham and Bevis Hillier (ed.), A Tonic to the Nation: The Festival of Britain 1951, London 1976, pp.83, 182, reproduced p.56.

1977

Henry Moore: Sculptures et dessins, exhibition catalogue, Musée de l’Orangerie des Tuileries, Paris 1977, reproduced p.63.

1978

Alan Wilkinson, The Drawings of Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1977, p.43.

1978

Henry Moore: 80th Birthday Exhibition, exhibition catalogue, Cartwright Hall, Bradford 1978, reproduced.

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery, London 1978, reproduced p.27.

1979

Alan G. Wilkinson, The Moore Collection in the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto 1979, pp.114–16 (plaster cast reproduced).

1979

John Read, Portrait of an Artist: Henry Moore, London 1979, p.93.

1980

Richard Calvocoressi, ‘Reclining Figure’, in The Tate Gallery 1978–80: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions, London 1981, p.117–18, reproduced p.117.

1987

Alan G. Wilkinson, Henry Moore Remembered: The Collection at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto, Toronto 1987, pp.135–7 (plaster cast reproduced).

1988

Susan Compton (ed.), Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Royal Academy of Arts, London 1988, p.230, reproduced p.97.

1996

Claude Allemand-Cosneau, Manfred Fath and David Mitchinson (eds.), Henry Moore From the Inside Out: Plasters, Carvings and Drawings, Munich 1996, pp.118–19 (bronze reproduced).

1998

Henry Moore 1898–1986: Eine Retrospektive zum 100. Geburtstag, exhibition catalogue, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna 1998, p.281.

2001

Robert Burstow, ‘Modern Sculpture in the South Bank Townscape’, in Elaine Harwood and Alan Powers (eds.), Festival of Britain, London 2001, pp.95–106 (bronze reproduced).

2001

Elizabeth Brown, ‘Moore Looking: Photography and the Presentation of Sculpture’, in Dorothy Kosinski (ed.), Henry Moore: Sculpting the 20th Century, exhibition catalogue, Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas 2001, p.287–95 (bronze cast reproduced p.294).

2003

Roger Berthoud, The Life of Henry Moore, 1987, revised edn, London 2003, p.271–2.

2006

John Read, ‘Working Model for Reclining Figure: Festival’, in David Mitchinson (ed.), Celebrating Moore: Works from the Collection of the Henry Moore Foundation, London 2006, pp.227–8.

2007

Jeremy Lewison, Henry Moore 1898–1986, Cologne 2007 (bronze cast reproduced p.65).

2008

Christa Lichtenstern, Henry Moore: Work-Theory-Impact, London 2008, pp.100–2, reproduced.

2008

Catherine Jolivette, ‘London Pride: 1951 and Figurative Sculpture at the South Bank Exhibition’, Sculpture Journal, vol.17, no.2, 2008, pp.23–36.

2010

Chris Stephens (ed.), Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2010, reproduced pp.188–9.

2011

Anita Feldman and Malcolm Woodward, Henry Moore: Plasters, London 2011, reproduced pp.54–5.

2012

Katerina Loukopoulou, ‘The Mobile Framing of Henry Moore’s Sculpture in Post-War Britain’, Visual Culture in Britain, vol.13, no.1, pp.63–81, reproduced p.75.

Technique and condition

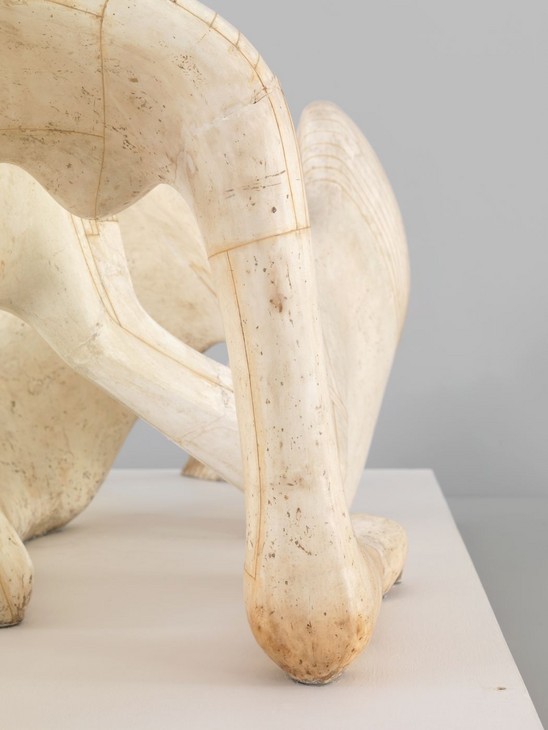

This is a large plaster sculpture of a reclining figure resting on a rectangular wooden base. To make this sculpture Moore first created a supportive armature onto which he applied successive layers of wet plaster. A visible steel rod connecting the right hand to the body provides evidence that this armature was made from iron (fig.1). Moore worked on the plaster with various tools as it set and dried before finally abrading the surface to create a smooth finish.

Detail of strings on Reclining Figure 1951

Tate T02270

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Detail of strings on Reclining Figure 1951

Tate T02270

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of strings on head of Reclining Figure 1951

Tate T02270

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Detail of strings on head of Reclining Figure 1951

Tate T02270

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Moore often added texture and surface designs to his sculptures by making marks using a variety of tools. Here, however, he has created detail by laying fine string across the surface of the sculpture according to a carefully executed design comprised of straight and curve lines (figs.2 and 3). The adhesive Moore used to attach the string to the surface has now aged, leaving a yellow tinge around the lines of string.

This plaster was used to make a mould of the sculpture from which bronze casts could be made. This process required a release agent to be applied to the surface of the plaster to ensure that the mould could be removed easily from the original while retaining as much surface detail as possible. The shiny finish on the surface may be a residual layer of this release agent.

Detail of staining on right arm of Reclining Figure 1951

Tate T02270

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Detail of staining on right arm of Reclining Figure 1951

Tate T02270

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of turquoise staining on left leg of Reclining Figure 1951

Tate T02270

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.5

Detail of turquoise staining on left leg of Reclining Figure 1951

Tate T02270

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The sculpture has sustained a number of cracks and losses to its surface as a consequence of the plaster’s fragility. A yellowish brown area on the figure’s right forearm (fig.4) is likely to be the result of damp causing iron staining to spread from the armature. A second area, this time on the left ankle, has acquired a turquoise-green tinge (fig.5). This colour usually originates from copper and may be a stain emanating from the internal armature or caused by bronze dust accumulating on the surface of the sculpture while at the foundry.

In 1997 the sculpture required extensive cleaning following a small fire in the control room at Tate Britain that led to it being covered in a fine layer of soot. The sculpture is unsigned.

Lyndsey Morgan

March 2011

How to cite

Lyndsey Morgan, 'Technique and Condition', March 2011, in Alice Correia, ‘Reclining Figure 1951 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, January 2014, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://wwwEntry

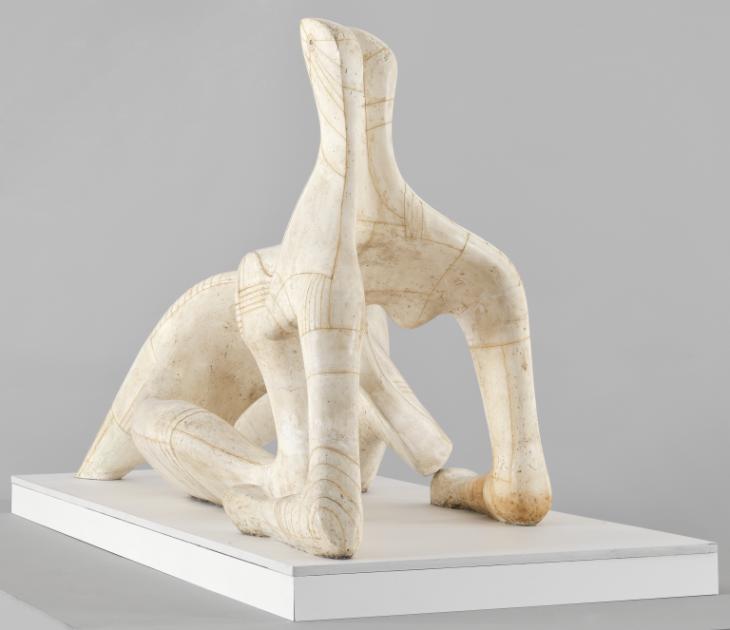

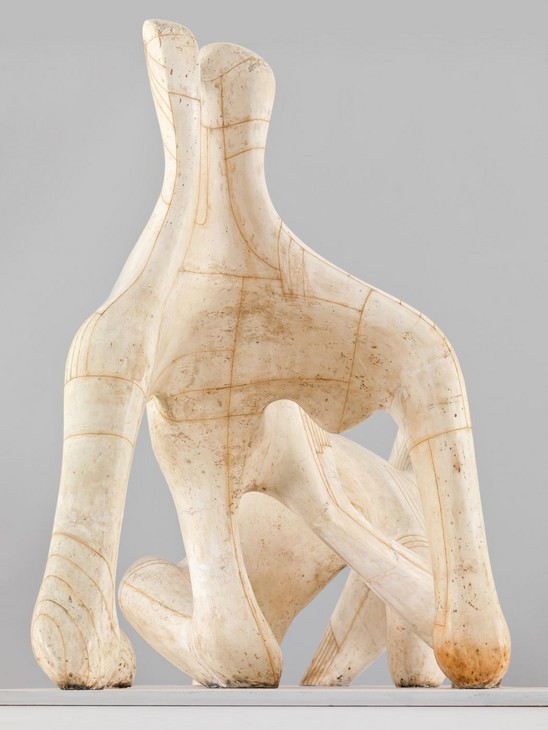

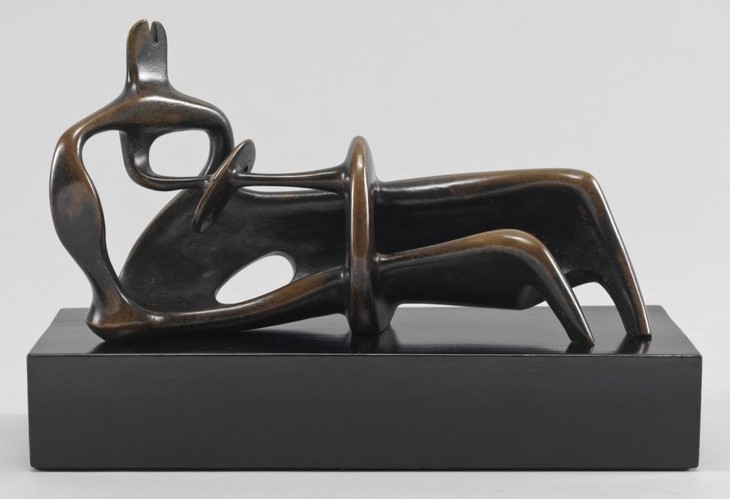

Originally commissioned by the Arts Council of Great Britain for the 1951 Festival of Britain, Henry Moore’s Reclining Figure is the original plaster from which a bronze edition of the sculpture was cast.1 It presents a reclining figure comprised of variously thin and bulbous tubular forms over which a dense network of lines created by string delineates and decorates the contours of the body.

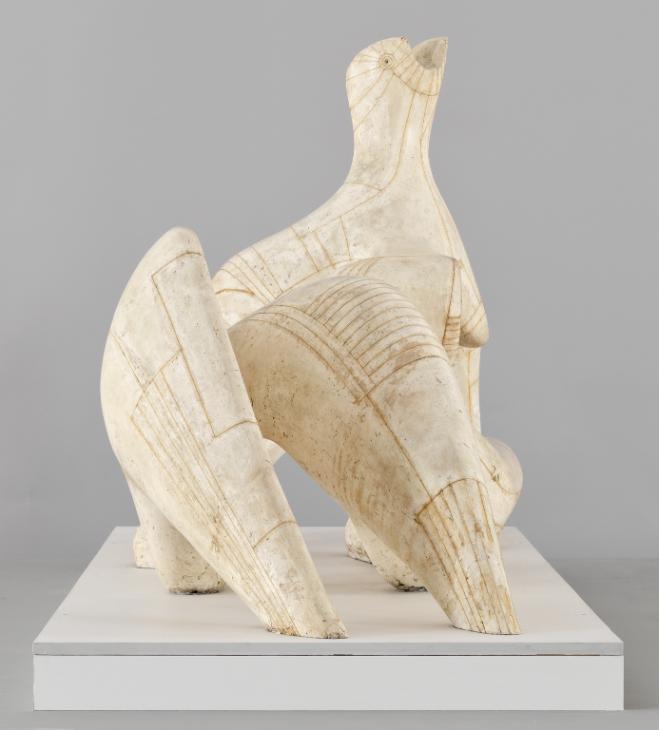

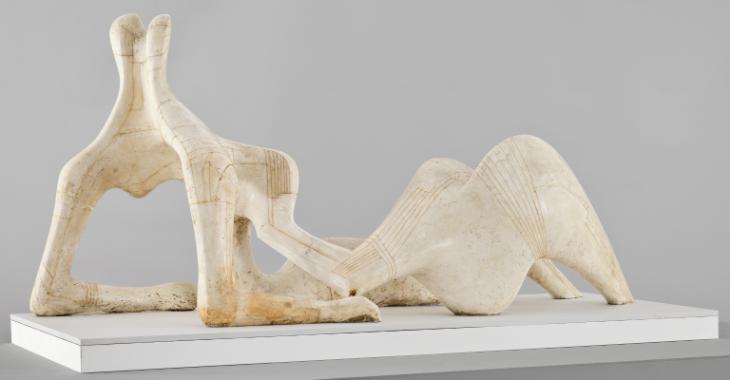

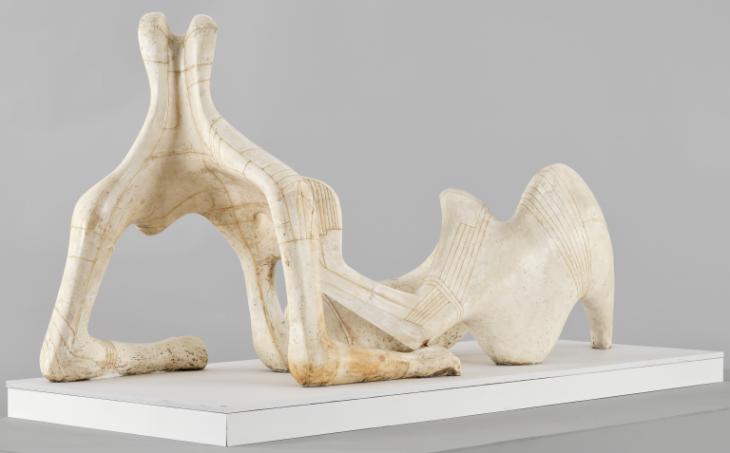

The head strains vertically upwards and features a U-shaped incision between two recessed eye sockets that from some angles may be regarded as an open mouth (fig.1). Extending vertically downwards from the two shoulders are arms that bend at right angles on the base so that the forearms point horizontally in the same direction as the body and legs. Both hands are rendered schematically, but while the left is clenched into a fist the right mitten-like hand rests flat on the base. The figure has no torso as such but a flat, concave chest that projects almost horizontally outwards and culminates in a barrel-like form. Rounded protrusions between the underside of the body and the armpit may be regarded as breasts. Two thin spurs, approximately the same diameter as the arms, project down from the lower corners of the barrel-like form and merge into legs that intertwine fluidly in an anatomically impossible fashion. While the right-hand spur juts out to the right before swelling into two large, rounded ridges that resemble knees, the left thigh lies flat on the base and only connects to its calf by curving into the arch formed by the nearest knee. Here the legs separate into two recognisable calves that get progressively thinner as they reach the base.

Henry Moore

Reclining Figure 1951 (view of right leg)

Tate T02270

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Henry Moore

Reclining Figure 1951 (view of right leg)

Tate T02270

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Reclining Figure 1951 (view from behind head)

Tate T02270

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Henry Moore

Reclining Figure 1951 (view from behind head)

Tate T02270

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Overall Reclining Figure has an open, skeletal form, although the scale and shape of some features – such as the right buttock, thigh and knee – have been exaggerated to give a sense of fleshy volume (fig.2). Viewing the sculpture from one end, it is possible to see all the way from the head to the ankles through a sequence of hollows that run through the body (fig.3).

Detail of right leg of Reclining Figure 1951 showing strings

Tate T02270

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Detail of right leg of Reclining Figure 1951 showing strings

Tate T02270

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of head of Reclining Figure 1951

Tate T02270

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.5

Detail of head of Reclining Figure 1951

Tate T02270

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

A network of thin strings embedded into the surface of the sculpture enhances its three-dimensionality, leading the eye across, around and beneath the figure’s body. The strings generally follow the contours of certain forms – such as the radial lines on the rounded face of the left breast – or their outline. For example, the strings encircling and running down the right leg emphasise the girth of the thigh and the length of the calf respectively (fig.4). On the figure’s head the strings have been used to draw attention to the two small depressions on either side of its convex face, which are suggestive of eyes. Two strands encircle each depression, with more radiating from the outer string (fig.5).

In May 1951 the critic Eric Newton described the bronze version of Reclining Figure as ‘the lithest and supplest of all of his creations’.2 He went on:

Bony though it is, it has a continuous liquid flow from end to end. Waves of movement run up the legs, rising like the swell of the sea, swinging round from front to back (if a design so completely grasped from every point of view can be said to possess a front and a back) thinning down to slim, rounded ridges, hardening and thickening into solid blocks, rising to a climax in the half-hollowed head, and sinking down along the bent arm that supports the shoulder and breast with a firm elbow.3

In her own description of the sculpture written almost sixty years later, the art historian Christa Lichtenstern similarly emphasised the sense of movement conveyed by the figure’s form:

Close inspection reveals that the decisive spatial impulse within the figure as a whole comes from the head. This towers above the bridge-like construction of the upper body, the long forearms resting on the base and reaching further back than usual. Standing behind the head, the viewer senses a powerful thrust passing from it to the upper arms and down through the rest of the figure. The energy embodied in this thrust moves forwards, renewing itself from cavity to cavity and seemingly pushing the chest towards the middle of the body. Pressing onward like a ship’s prow, it solidifies into the largest mass in the figure, at the area of the chest. From here two elements descend on either side, one vertically, the other diagonally, and lead to the lower body. The thrust passes to the relatively solid legs, placed diagonally to the upper body, and eventually subsides in two simple, broad, wave shapes. A sequence of firm support, upward movement and release of tension thus governs the spatial composition of the figure.4

Origins and facture

The process of making Reclining Figure was recorded by the filmmaker John Read for a television programme commissioned by the BBC titled Henry Moore.5 According to film historian Katerina Loukopoulou, Read’s film ‘offered an innovative audio-visual analysis of Moore’s sculptures and the creative process that produced the Reclining Figure’, noting that Read presented Moore as an artistic labourer, working to transform his raw materials into sculptural objects.6 Recorded over a period of six months from October 1950 to late March 1951, the final part of the film charts the creation of Reclining Figure. Beginning with Moore executing the preliminary drawing in his studio, the film follows the making of the plasticine maquette and full-size plaster before moving to the Gaskin foundry where the bronze casting process was filmed. The unfolding creative process culminates in a sequence filmed in Moore’s garden, in which the newly completed bronze version of Reclining Figure spins in front of the camera: ‘the sculpture’s holes become an ever changing form, as the view through these holes continuously changes with the spinning motion’.7 In 2008 John Read explained that in presenting the sculpture in this way he aimed to take the viewer on a ‘voyage of exploration’.8 In addition to its innovative mobile framing techniques, Read’s film provided a unique insight into Moore’s sculptural practice. The film was broadcast on 30 April 1951 to coincide with Moore’s solo exhibition at the Tate Gallery and his participation in the Festival of Britain’s South Bank exhibition in London, both of which opened in May 1951. The film was positively reviewed, and copies were subsequently sent to the British Council, the British Film Institute and the Arts Council for non-theatrical screenings and film festivals.9

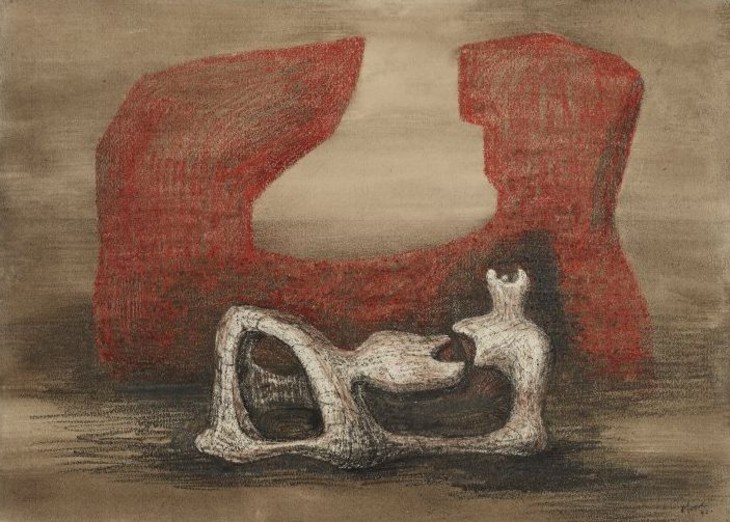

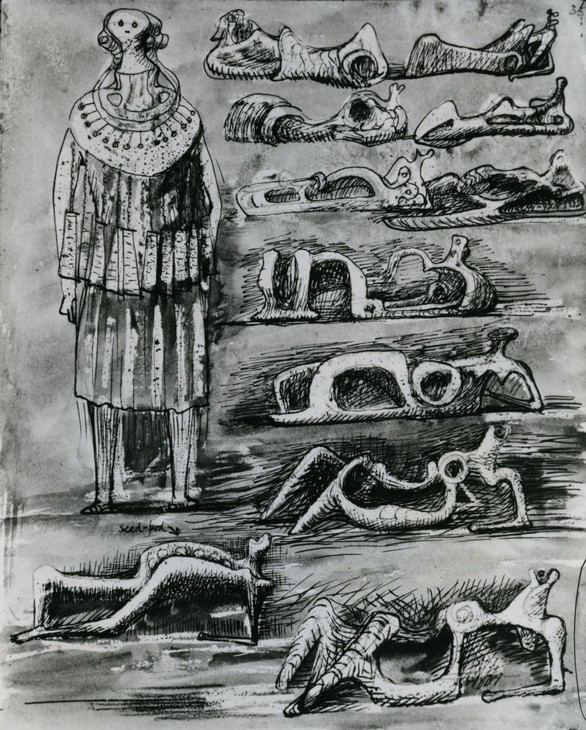

The Arts Council had initially asked Moore to make ‘a carving of a family group symbolising “Discovery”’ for inclusion in the South Bank exhibition.10 It is likely that the commissioning board had envisaged a work similar to Moore’s Family Group 1949 (Tate N06004), which had been commissioned for and recently installed at Barclay School in Stevenage, Hertfordshire. However, Moore instead chose to make a reclining figure, one of his favoured subjects prior to the Second World War and one that he was evidently keen to develop. A sketch made in 1949 demonstrates how Moore experimented with designs that reconfigured the basic shape of the reclining figure (fig.6). The figure in the top left corner of the page bears a resemblance to Reclining Figure with its splayed arched legs, the curved indentation in its head, and the angle of its left arm. These sketches also show how Moore used repeated lines to enhance the three-dimensionality of his drawn figures and may have informed his use of string in the final sculpture.

Henry Moore

Reclining Figures 1949

Graphite, charcoal, wax, crayon, coloured wash, pen and ink on paper

394 x 571 mm

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.6

Henry Moore

Reclining Figures 1949

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Henry Moore

Study for Festival Reclining Figure c.1950

Graphite, wax crayon, watercolour wash, pen and ink on paper

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.7

Henry Moore

Study for Festival Reclining Figure c.1950

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

In Read’s film Moore was shown drawing Study for Festival Reclining Figure c.1950 (fig.7). The sequence of thin reclining bodies on the right of the page illustrates how Moore refined his composition for the final sculpture. For example, the studies towards the lower right of the page show how a hollow tubular form was transformed into the more solid, barrel-like chest component. For this sketch Moore drew the figures in wax crayon before applying a wash of dark watercolour across the page.

Henry Moore

Small Maquette No.1 for Reclining Figure 1950

Bronze

115 x 240 x 96 mm

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.8

Henry Moore

Small Maquette No.1 for Reclining Figure 1950

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Small Maquette No.2 for Reclining Figure 1950

Bronze

115 x 234 x 92 mm

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.9

Henry Moore

Small Maquette No.2 for Reclining Figure 1950

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

After making a number of drawings for his reclining figure Moore then constructed a small model of the sculpture to test out the design in three dimensions (fig.8). In 1968 Moore explained to the photographer John Hedgecoe that, ‘when I make a small maquette, it is rather like an architect making a sketch for a building on an envelope. In his mind it is a full-size building ... It’s all a question of mental scale and not physical size’.11 In Read’s film Moore is seen working on his initial maquette in plasticine, which Moore preferred to clay as it was more malleable and did not dry out as quickly. Moore incised the linear design onto the surface of the maquette, demonstrating that this was an integral part of the sculpture from an early stage. In actuality, the making of Reclining Figure did not follow the linear process depicted in Read’s film. For example, Moore made two maquettes of the reclining figure while developing the design in three dimensions, each with slight variations. In comparison to the version that was eventually enlarged, the second, Small Maquette No.2 for Reclining Figure 1950 (fig.9), is much thinner and more angular.

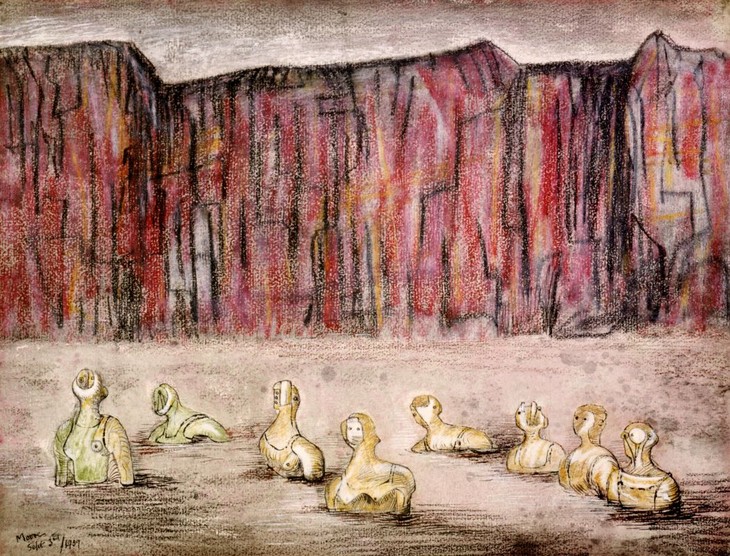

The presence of a small round element within the U-shaped head of the second maquette links it to an earlier drawing from 1942. In Reclining Figure and Red Rocks 1942 (fig.10) Moore set a skeletal reclining figure against a red rock formation, the shape of which seems to echo the silhouette of the body. Nestled in the concave upper edge of the figure’s head is a small ball, perhaps suggestive of an eye or a tongue. That Moore included this feature in one of his preparatory models for Reclining Figure suggests that he had planned to translate the open structure of the drawn sculpture and specific elements of its form into three dimensions years before he made it. It also suggests that he approached the Arts Council’s commission with relatively fixed ideas about what he wanted to create.

Henry Moore

Working Model for Reclining Figure 1950

Plaster with surface colour

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.11

Henry Moore

Working Model for Reclining Figure 1950

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

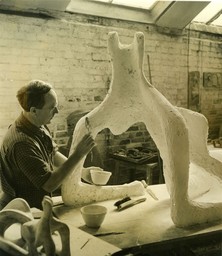

Henry Moore working on Reclining Figure in his studio c.1950

Tate T02284

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.12

Henry Moore working on Reclining Figure in his studio c.1950

Tate T02284

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

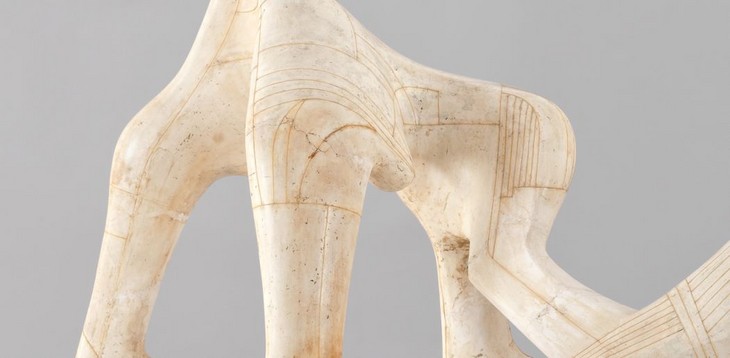

Having settled upon the basic design of the sculpture, Moore then created a working model in plaster (fig.11). Slightly larger than the maquettes, this working model allowed Moore to further refine his design. He used a red pencil to draw contour lines onto the surface of this working model sculpture, and unlike the lines inscribed on the maquette, which are markedly different from those that appear on the final Reclining Figure, these red pencil lines provided the blueprint for the design executed with string in Tate’s plaster. However, close inspection of the working model reveals that Moore drew more lines on the surface of the working model than he used on the full-size sculpture. The working model was later cast in bronze in an edition of seven plus one artist’s copy.

After completing the working model Moore and his assistants used it as a template to scale up the full-size sculpture. This would have required them to measure specific points on the surface of the working model to ensure that the proportions of the sculpture were retained during the enlargement process. Read’s film shows Moore comparing the design of the large scale plaster with that of the working model to ensure the accuracy of the enlargement. Work on Tate’s plaster would have begun with the construction of an armature, which was made up of iron rods bent into the rough shape of the sculpture. Over this metal structure Moore added layers of plaster to build the forms to their desired shape and thickness. When this process was complete Moore began working on the surface texture, using an array of tools including chisels and files to smooth the plaster to the desired finish (fig.12). Moore found plaster to be a very useful material because it could be ‘both built up, as in modelling, or cut down, in the way you carve stone or wood’.12

As the curator Alan Wilkinson has noted, the principal ‘innovative feature’ of this sculpture is Moore’s ‘use of strings glued to the surface’.13 It is unclear exactly how Moore applied the string lines to the surface of the plaster so accurately, but it is possible that he lightly scored the linear design into the surface with a sharp point and ruler to act as a guide. The lengths of string are slightly raised in relation to the surface. According to Wilkinson, ‘these strings serve the same function as the two-way sectional lines in the drawings; that is, they move in two directions, both down and across the forms, thus leading our eye over the three-dimensional shape beneath’.14 Wilkinson also suggested that the lines ‘serve to indicate the subtle curves and hollows’.15

Henry Moore

Reclining Figure 1951

Bronze

1060 x 2285 x 737 mm

Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.13

Henry Moore

Reclining Figure 1951

Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Tate’s version of this sculpture is one of Moore’s earliest surviving large plasters.17 At this stage in his career Moore regarded his plaster sculptures as stages towards the production of a bronze and not works of art in their own right. As Moore’s former assistant David Mitchinson has explained, ‘Moore had no particular feeling for the plasters and many early examples were destroyed, either deliberately at the foundries or through neglect’.18 During the 1950s, however, when demand for exhibitions of his work increasing, Moore began exhibiting plaster versions when bronzes were unavailable. In fact, an additional plaster cast of Reclining Figure was made for the British Council some time in the 1950s by one of Moore’s assistants, using the original plaster as a guide. This cast was included in the British Council’s touring exhibition of Moore’s work, which visited Europe, Canada, New Zealand and South Africa between 1953 and 1959, and is now housed in the collection of the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO) in Toronto.19

Moore’s attitude towards his plasters shifted over time, and he came to see them not simply as intermediary stages in the creative process but as unique works of art. In the early 1970s Moore declared that, ‘These are not plaster casts; they are plaster originals ... they are actual works that one has done with one’s hands’.20 In 1973 Moore recounted the moment when he began to reconsider the value of his plasters:

A friend who works at the Victoria and Albert Museum came out one day just as we were breaking up some plasters and said, ‘But why do that, because sometimes the original plaster is actually nicer to look at than the final bronze’. He was right because sometimes an idea you’ve had and that you’ve made in the original material or plaster can suit it better than what the final bronze may do ... So, this led to the idea of not destroying the plasters, leaving me with a great many of them that I would not sell but wanted to find proper homes for.21

Having decided to stop destroying his plasters, Moore was then faced with the problem of what to do with them. Selling them on the open market would increase the risk of casts being made without his permission, but he did not have the required space to keep the plasters indefinitely. A solution was found by way of philanthropic gifts, first to the AGO in 1974 and then to the Tate Gallery in 1978.

Having decided to give the AGO and Tate examples of the original plasters, in the early 1970s Moore’s studio assistants John Farnham, Michael Muller and Malcolm Woodward set about repairing the damaged plasters and removing traces of resin sealant from their surfaces. The brittleness of plaster and the stress placed on the sculpture during the casting process had led to it being damaged and a number of cracks can be seen on its surface, particularly on the upper right arm and the central cylindrical form linking the chest and legs (fig.14).

Detail of repairs to Reclining Figure 1951

Tate T02270

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.14

Detail of repairs to Reclining Figure 1951

Tate T02270

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of turquoise staining on left leg of Reclining Figure 1951

Tate T02270

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.15

Detail of turquoise staining on left leg of Reclining Figure 1951

Tate T02270

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

It is evident that the adhesive holding the strings in place, which is believed to be an epoxy resin, has become discoloured over time, leaving orange-brown lines around the strings (fig.15).22 The plaster itself has also changed colour. Areas of cleaner, whiter plaster can be identified where the surface has been repaired, especially at the points where the sculpture rests on the base.

Sources and development

In 1968 Moore identified Reclining Figure as a particularly important work that marked a breakthrough in his exploration of the relationship between masses and voids:

The ‘Festival Reclining Figure’ is perhaps my first sculpture where the space and the form are completely dependent on and inseparable from each other. I had reached the stage where I wanted my sculpture to be truly three-dimensional. In my earliest use of holes in sculpture, the holes were features in themselves. Now the space and form are so naturally fused that they are one.23

Reclining Figure may be regarded as the culmination of Moore’s pre-war investigations into the use of space within the sculpted reclining figure. After carving his first reclining figure in c.1924, the reclining figure propped up on its elbows with raised knees emerged as a central motif in Moore’s work in the late 1920s and henceforth became his most frequently recurring subject. In 1947 Moore accounted for his preference for the reclining figure, stating that:

There are three fundamental poses of the human figure. One is standing, the other is seated, and the third is lying down ... of the three poses, the reclining figure gives most freedom compositionally and spatially. The seated figure has to have something to sit on. You can’t free it from its pedestal. A reclining figure can recline on any surface. It is free and stable at the same time. It fits in with my belief that sculpture should be permanent, should last for eternity. Also, it has repose, it suits me – if you know what I mean.24

Michelangelo

Dawn c.1520–34

Medici Chapel, Basilica of San Lorenzo, Florence

Fig.16

Michelangelo

Dawn c.1520–34

Medici Chapel, Basilica of San Lorenzo, Florence

By working within the constraints suggested by the subject of the reclining female figure Moore could conduct focused formal experiments with regard to composition (in the position of the body and its limbs) and space (in the projection of its limbs into space and the gaps formed by the pose). In addition to these perceived virtues, Moore believed that because the subject of the reclining figure was so well known and understood, it allowed him more freedom to depart from conventional, naturalistic modes of representation. Moore was clear that he did not seek to imbue his reclining figures with a specific meaning, but rather to use the motif as a starting point for formal experiments:

I want to be quite free of having to find a ‘reason’ for doing the Reclining Figures, and freer still of having to find a ‘meaning’ for them. The vital thing for an artist is to have a subject that allows [him] to try out all kinds of formal ideas – things that he doesn’t yet know about for certain but wants to experiment with, as Cézanne did in this ‘Bathers’ series. In my case the reclining figure provides chances of that sort. The subject-matter is given. It’s settled for you, and you know it and like it, so that within it, within the subject that you’ve done a dozen times before, you are free to invent a completely new form-idea.26

Henry Moore

Reclining Figure 1929

Brown Hornton stone

Leeds City Art Gallery

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.17

Henry Moore

Reclining Figure 1929

Leeds City Art Gallery

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Recumbent Figure 1938

Green Hornton stone

object: 889 x 1327 x 737 mm, 520 kg

Tate N05387

Presented by the Contemporary Art Society 1939

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.18

Henry Moore OM, CH

Recumbent Figure 1938

Tate N05387

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Reclining Figure may be understood as a development of Moore’s earlier reclining figures, such as Reclining Figure 1929 (fig.17) and Recumbent Figure 1938 (fig.18), carved in Brown and Green Hornton stone respectively. Both of these sculptures present a female figure lying down with the belly and legs extending to the right of an upright head and shoulders. Furthermore, in both cases the figure rests on its right elbow and has bent knees. A comparison between these works illustrates Moore’s changing approach to negative space in his sculpture. While the gap between the left arm and head in the 1929 sculpture seems to be a natural consequence of the figure’s pose, the holes in Recumbent Figure are more explicitly integrated into the sculpture’s design and may even be seen as formal elements in themselves. In 1937 Moore explained that ‘a hole can itself have as much shape-meaning as a solid mass’.27 He found that by carving through the stone he could create holes that served to open out the inside of the sculpture, enhancing its three-dimensionality. In doing so Moore believed that he was replicating ‘nature’s way of working stone’, perhaps referring to the way that weathering creates rounded holes in rocks and pebbles.28

Henry Moore

Reclining Figure 1939

Bronze

Tate T00387

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.19

Henry Moore

Reclining Figure 1939

Tate T00387

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

If space is a willed, a wished-for element in the sculpture, then some distortion of the form – to ally itself to the space – is necessary. At one time the holes in my sculpture were made for their own sakes. Because I was trying to become conscious of spaces in the sculpture – I made the holes have a shape in its own right, the solid body was encroached upon, eaten into, and sometimes the form was only the shell holing the hole. Recently, I have attempted to make the forms and the spaces (not holes) inseparable, neither being more important than the other. In the last bronze, Reclining Figure, I think I have in some measure succeeded in this aim. What I mean is perhaps most obvious if the figure is looked at lengthways from the head end through to the foot end and the arms, body, legs, elbows etc., are seen as forms inhabiting a tunnel, in recession. Seen in plan the figure has ‘pools’ of space.32

Although Moore believed that Reclining Figure marked a turning point in the way it balanced space and form, his use of holes and negative space had been analysed for a number of years prior to the execution of this sculpture. For example, in 1948 the perceptual psychologist Rudolf Arnheim wrote an essay titled ‘The Holes of Henry Moore: On the Function of Space in Sculpture’.33 In this essay Arnheim asserted that through Moore’s use of holes and space, ‘the sculptural body ceases to be a self-contained, neatly circumscribed universe. Its boundary has become permeable’.34 According to Arnheim, by breaking down the distinction between the sculptural object and its environment Moore disrupted attempts to conceive the sculpture as a discrete and tangible whole, becoming instead a series of different stages or zones: ‘many a figure of Henry Moore’s captures portions of space and makes them a part of it. Much less solid than the wood, stone, or metal with which they unite, these air-bodies nevertheless condense into a transparent substance, which mediates between the tangible material of the state and the surrounding empty space’.35 Despite the figures being broken up in this way Arnheim suggested that Moore’s sculptures remained recognisable as human figures because, ultimately, ‘perceptual unity does not require physical continuity’.36

The Festival of Britain

During the 1951 Festival of Britain the bronze version of Reclining Figure was one of a number of sculptures displayed in the South Bank exhibition (fig.20). The festival was intended to showcase Britain’s technological and cultural future and the exhibition comprised a series of pavilions telling the interwoven story of the ‘Land and People of Britain’, presenting the nation’s future within the context of modernist design and scientific discovery.37 The exhibition site contained numerous contemporary works of art commissioned for the festival, including sculptures by Reg Butler, Frank Dobson, Jacob Epstein and Barbara Hepworth. Moore’s sculpture seemed to adhere positively to the festival’s two central themes. It was positioned in front of the Land of Britain (or ‘Country’) Pavilion, which addressed Britain’s agricultural history and the relationship between the people and the land, which in turn activated the correspondences found in Moore’s earlier work between body and landscape.

Henry Moore

Reclining Figure 1951 installed on the South Bank during the Festival of Britain 1951

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.20

Henry Moore

Reclining Figure 1951 installed on the South Bank during the Festival of Britain 1951

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Despite these accounts, in 1988 the critic Richard Cork argued that in making Reclining Figure Moore spurned ‘all thought of cultivating facile optimism to meet the mood of a festival which celebrated Britain’s emergence from the prolonged austerity of war and its immediate aftermath’.42 Cork asserted that in this work Moore ‘refused to concoct a sculptural placebo for the entertainment of the crowd ... Moore knew, as well as any of the younger artists who reflected the unease of the post-war period in their work, that scant comfort could be derived from the uneasy “peace” Britain now experienced’.43 The extent to which Moore’s sculpture resisted the tenor of the festival may be indicated by the comparisons drawn by some viewers, as recorded by Moore’s biographer Roger Berthoud, between Reclining Figure and the victims of Nazi concentration camps, interpreting the sculpture as ‘a human form in an advanced stage of decomposition which has been disemboweled, partially decapitated and had both feet severed’.44

When discussing the display of his sculpture in the South Bank exhibition, Moore stated:

I knew that the South Bank would only be its temporary home, so I didn’t worry about where it was placed. If I had studied a Festival site too carefully, the figure might never have been at home anywhere else. As it was, I made the figure, then found the best position I could. I was simply concerned with making a sculpture in the round.45

What Moore regarded as ‘the best position’ appears to have been one of maximum visibility. As the art historian Arie Hartog has explained:

Visitors entering the site through the Chicheley Street gate, one of the smaller entrances, saw the sculpture from far off, stretching across their field of vision. This established the left-hand side of the piece as the main view, intended to be seen from a distance. By contrast, visitors making their way from the main entrance to one of the restaurants encountered the other, rear side of the sculpture at much closer quarters. The essential point is that the figure was set up in the middle of, and at right angles to, the approximately fifteen-meter wide road running from the ‘Country’ pavilion to the buildings in York Road. What visitors saw first, then, was the outline of a long reclining figure with one element easily identifiable as a head. And not only could they scarcely overlook it; they also had to walk past one of its ends.46

Observing in 1951 that the position of the sculpture influenced how it was understood, Hendy regarded Reclining Figure to be in a poor position:

In this case alone the Exhibition might be said to have let down the artist, for, though the Reclining Figure has pride of place in the Fairway from the main gate, the foreground is too large and the background, a misplaced rockery, is too petty and broken into irritating lumps, which dispute with the rhythm of the figure’s far more natural forms.47

Although reviews of the South Bank sculptural displays were mixed, responses to Moore’s contribution were generally positive. An unnamed critic reviewing the sculpture for the Architectural Review concluded that:

there are only three, or perhaps four, works of sculpture which live in their own right – as something more than evidence of the taste and talent of their creators. One is Henry Moore’s reclining figure ... in this the feeling of power in repose conveyed by the posture and by the dynamo-like conformation of the chest or diaphragm is reinforced by the raised linear patterning of the bronze with its resultant sense of surface tension.48

Writing in the Listener critic Francis Watson similarly concluded that Moore’s sculpture was ‘superbly weighted and balanced, it shows Moore’s mastery of the equal use of space and mass and the unimpaired and unexploited vitality of our most celebrated (and perhaps busiest) sculptor’.49 However, countering these positive voices, the critic David Sylvester concluded that ‘not one of the larger sculptures on the South Bank is really successful’.50 Of Moore’s contribution he wrote that:

Reclining Figure has been worked out with superb logic and resourcefulness as a configuration of masses and voids, and the tunnel which cuts a passage through its length is the most ingenious variant of this idea that Moore has devised. But one suspects that Moore has conceived this work purely as a sculptural object, not as an image, because the forms, considered as signs, are either conventional or arbitrary. The head is just as much a cliché as are the heads in official portraits by Royal Academicians. The legs have no connection with the structure and the articulation of human legs, nor have they the justification of possessing a metaphorical significance: they are meaningless shapes determined solely by the exigencies of design. And the drum-like form which acts as a sort of projecting thorax seems a quite gratuitous interpolation (which did not seem in the smaller version of this work, simply because it was smaller). This latest addition, then, to Moore’s long series of ‘opened-out’ reclining figures has too little contact with life to carry the imaginative conviction and dramatic power of its predecessors. And, after all, it is not surprising that his handling of this theme should have reached the stage of empty, if impressive, virtuosity, since he has been exploiting it now for twenty years.51

For Sylvester, Moore’s sculpture was simply an exercise in form and structure, taking twenty years of experiments with mass and space to their inevitable conclusions but emptying them of metaphorical and emotional content. Perhaps referring to works such as Family Group 1949, Sylvester concluded that:

when one considers how much promise as well as accomplishment there is in the more ‘humanist’ work which he has produced in recent years, one wonders why Moore bothers to go on exercising a means of expression which was natural to the 1930s, a very different age from ours. It is as if he were afraid of keeping in step with himself.52

The Festival of Britain display, John Read’s film, and his solo exhibition at the Tate Gallery certainly exposed Moore’s work to a larger number of people than ever before, and his reclining figures secured Moore’s work within the public imagination. Moore’s ‘holes’ became the subject of a number of satirical cartoons, including one published in Punch in 1951, which depicted a husband and wife in front on the sculpture on the South Bank.53 Looking at the hole in the figure’s torso the husband asks, ‘That reminds me, dear – did you remember the sandwiches?’ Fourteen years later the critic David Thompson noted that:

if a cartoonist wants to make fun of modern art and draw an immediately recognisable symbol of it, the likelihood is that he will for a painting depict a face with both eyes on the same side of the nose, or for a sculpture show a bulbous potatoe-shape with a hole through it. In other words, he will make an explicit reference, in painting to Picasso, and in sculpture to Henry Moore.54

Thompson suggested that this type of parody was in fact a ‘back-handed compliment’, since cartoons identified Moore and his characteristic use of holes as exemplary of modern art.55

In 1978 the critic William Feaver reflected that ‘Moore-ish holed sculpture became the longest running modern art joke’.56

In 1978 the critic William Feaver reflected that ‘Moore-ish holed sculpture became the longest running modern art joke’.56

Critical reception

During the 1950s Reclining Figure became one of Moore’s most well-known sculptures. The inclusion of a plaster cast of the sculpture in the British Council’s touring exhibition of Moore’s work brought it to the attention of an international audience. The sculpture was seen in Canada (1955–6), New Zealand (1956–7), South Africa (1957), Southern Rhodesia (1957), Portugal (1959), Spain (1959) and Poland (1959).57 In his review of Moore’s exhibition in New Zealand the art historian Mark Stocker argued that the show ‘was an Antipodean equivalent of “Manet and the Post-Impressionists” (1910–11, London) or the Armory Show (1913, New York). Belatedly, not without protest and yet decisively, it brought the world of modern art into New Zealand’.58

Similarly, the art historian Katarzyna Murawska-Muthesius has charted the impact of Moore’s solo exhibition in Poland, which opened in Warsaw in October 1959.59 In this context the British Council presented Moore as a ‘Modernist Warrior’, a cipher of British diplomacy, democracy and artistic freedom in the face of the social realism championed by the Polish government under the influence of the Soviet Union. Murawska-Muthesius recorded that although Moore was framed as a ‘formalist “degenerate”’, within the ‘militant Stalinist discourse’ that prevailed in the contemporary Polish media, his exhibition was ‘a dizzying success with both critics and the public’.60

In 1960 Tate’s sculpture was exhibited in Moore’s mid-career exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery in London. The exhibition was generally well received in the press, with the critic David Thompson declaring in the Times that:

the quite extraordinary power and authority of the finest pieces in the exhibition exist in a sort of loneliness and silence, withdrawn from the madding crowd. This in itself is one of the many paradoxes inherent in the appeal of Moore’s art. As often as it retreats from immediate human contact and sympathy, it solicits them by its strong sense of pathos.61

Although by 1960 Moore was recognised as one of Britain’s foremost artists, responses to the show also revealed disenchantment with his perceived aspiration to convey universal truths about humanity. In his review of the exhibition published in Art International, the critic Lawrence Alloway suggested that the sculptures on display at the Whitechapel formed ‘an awkward repertoire of heroic gestures’.62 While Alloway noted that Moore’s earlier carvings developed the unique qualities of his raw materials, in the recent works on display ‘the human attributes of pose or anatomical detail seem to grow neither out of a full mastery of the human body nor out of an intimate response to the material itself’.63 Alloway went on to compare the exhibition to the visual spectacle of the opera, where the nuances of individual characters are sublimated into the whole: ‘Similarly with Moore’s figures of the past decade: their gestures and poses seem less than heroic within the heroic massing. (One is somewhat reminded of the helplessness of di Chirico’s gladiators in his arena paintings of the 20s).’64 Alloway proposed that the problem of Moore’s work was that it displayed a conscious attempt to convey a comprehensive humanist sentiment. ‘Obviously out of the highest motives,’ Alloway remarked, ‘Moore is hoping to give his public sculptures a worthy message, a stirring content’. Yet the critic suggested that Moore’s perceived attempt to access a universal language, eschewing local contexts, made his work subject to generality and obsolescence: ‘Moore seems dissatisfied with what he can reach from his own situation. As a result all he offers, despite his ambition, is a sculpture of empty Virtues’.65

Beyond the immediate responses and subsequent art historical accounts prompted by its inclusion in exhibitions, Reclining Figure has also generated a sustained body of art writing. In 1959 the psychologist Erich Neumann identified the sculpture as a transitional work, bridging Moore’s ‘Helmet Heads’ of the early 1950s (see Helmet Head No.1 1950, Tate T00388) to his large female reclining figures made later that decade (see Draped Reclining Woman 1957–8, Tate T06825). Interestingly, Neumann treated what is now regarded as the rear of the sculpture, the figure’s right side, as its front. From this perspective he argued that Moore’s sculpture ‘emphasises, in its clear outlines and ponderous massiveness, the “closed” quality of organic form, and the great sweeping line sketches the picture of a woman who, notwithstanding a certain elegant beauty, is bound quietly and steadfastly to the earth’.66 However, Neumann also noted that when seen from the opposite side, ‘the same sculpture shows us something completely different. Jagged, wild, charged with sinister energy, this recumbent figure is more like the destroying goddess of 1939 [fig.19]’.67 In linking the sculpture to Reclining Figure 1939, Neumann proposed that the 1951 work may be understood as a ‘deathly machine-like character’.68 Instead of the rotund and fecund female reclining figures epitomised by Recumbent Figure 1938, the ‘deadly and destructive opposite finds expression in the naked skeleton, stripped of all organic fullness and reduced to the spectral machine’.69 As the curators Penelope Curtis and Keith Wilson have asserted, ‘although his reclining figures have often been seen as essentially pastoral’, from the vantage point of the post-war period Reclining Figure 1951 ‘resembles a victim of war’.70

Others have also interpreted Reclining Figure in more anxious terms than those provided by the positivity of the Festival of Britain. For example, in 1960 the art historian Will Grohmann described the work as ‘terrifying’, stating that:

it is the culmination of the series of non-naturalistic configurations that represent a symbiosis between nature and ghostly specters ... Whether this ‘Reclining Figure’ is an incarnation of evil rather than good, of death rather than life, it is not easy to decide, but despite the hollow structure, it does not belong to the ‘hollow man’ species. Its majesty is unmistakable; it stretches straight up, rests upon the wedge of the arms and thrusts powerfully off with its shin bones; its vitality lies in the immense tension that runs from the base of the feet to the head, whose cleavage indicates conflict, the ‘age of anxiety’. The frightening figure reveals its meaning most clearly when seen from the side and back, for there the hollow shapes form the entrance to a kingdom of the dead.71

Henry Moore

September 3rd 1939 1939

Graphite, wax crayon, chalk, watercolour, pen and ink on paper

306 x 398 mm

The Moore Danowski Trust (The Henry Moore Family collection)

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.21

Henry Moore

September 3rd 1939 1939

The Moore Danowski Trust (The Henry Moore Family collection)

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Family Group 1949, cast 1950–1

Bronze

object: 1540 x 1180 x 700 mm, 475 kg

Tate N06004

Purchased 1950

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.22

Henry Moore OM, CH

Family Group 1949, cast 1950–1

Tate N06004

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Parallels may be drawn between Reclining Figure and Moore’s previous responses to the Second World War by viewing the upward thrust of the sculpture’s head in light of the drawing September 3rd 1939, the title of which refers to the day that the war was announced (fig.21). The drawing depicts a group of pale, rigid and vertically-oriented bodies partially submerged in the sea in front of a red cliff-face. Reflecting the pervading sense of uncertainty about the future, it is unclear whether the figures are emerging from the water, or sinking into it for only their heads and shoulders can be seen. While the stillness of several figures conveys a sense of eerie calm, others break this stillness, appearing to strain their necks and scream. One such figure, the third from the right, has eyes on either side of an open mouth, which screams upwards to the sky. Similarly, Richard Cork has noted that Reclining Figure ‘seems to gape up at the sky, in the unlikely hope that reassurance might be discovered there’.72

Another variation of this open-mouthed head can be seen in the male figure featured in Maquette for Family Group 1945 (fig.22). The critic Herbert Read described this motif as a ‘surrealist split-head’.73 Interpreted as a perpetual, silent scream, the anxiety inferred by such an image could align Reclining Figure with Francis Bacon’s Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion c.1944 (Tate N06171) or Reg Butler’s Circe Head 1952–3 (Tate T03867).74 Bacon and Butler’s screaming, thrusting heads may equally be seen as expressions of terror in the face of war, and in the post-war years the horror they communicated was not only retrospective. As Cork explained, ‘Hiroshima had taught him [Moore] that the sky could now unleash a destructive capacity more devastating by far than anything inflicted on London during the Blitz. Hence the apprehensiveness with which this fractured head looks upwards, seeming to gasp for air’.75 Nonetheless, Cork concluded that ‘in the end, though, the Festival of Britain sculpture is a resilient image, braced for defiant survival. Its sinuous rhythms denote a woman whose pared-down structure belies her supple strength’.76 Similarly, the curator Christa Lichtenstern has argued that Reclining Figure ‘offered hope to receptive viewers in the turbulent post-war world’ due to ‘its inner strength’.77

The Henry Moore Gift

Reclining Figure was presented by Henry Moore to the Tate Gallery in 1978 as part of the Henry Moore Gift. The Gift comprised thirty-six sculptures in bronze, marble and plaster and was exhibited in its entirety alongside Tate’s existing collection of Moore’s work in an exhibition celebrating the artist’s eightieth birthday, which opened in June 1978. A press release was duly prepared announcing that ‘The group [of sculptures] is the most substantial gift of works ever given to the Tate by an artist during his lifetime’.78 Reclining Figure was included in the exhibition and displayed in gallery twenty-six alongside Upright Internal/External Form 1952 (Tate T02272). The exhibition was attended by over 20,500 people and nearly 11,000 copies of the catalogue were sold.79 At the close of the exhibition in late August 1978 the Director of Tate Norman Reid reflected in a letter to Moore’s daughter Mary Danowski that although he was sad to see the exhibition come to an end ‘we have the consolation of the splendid group of sculptures which Henry has presented to the nation’.80

Alice Correia

January 2014

Notes

The official title of the work is Reclining Figure, although it has also been known as Reclining Figure: Festival. See, for example, Anita Feldman and Malcolm Woodward, Henry Moore: Plasters, London 2011, p.54.

Eric Newton, ‘What Do The Public Think?: Henry Moore’s New Work at the Festival’, Art Fortnightly, 11 May 1951, Henry Moore Foundation Archive.

Henry Moore, dir. John Read, television programme, broadcast BBC, 30 April 1951, http://www.bbc.co.uk/archive/henrymoore/8801.shtml , accessed 13 January 2014.

Katerina Loukopoulou, ‘The Mobile Framing of Henry Moore’s Sculpture in Post-War Britain’, Visual Culture in Britain, vol.13, no.1, 2012, p.63.

Alan G. Wilkinson, Henry Moore Remembered: The Collection at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto, Toronto 1987, p.137.

The Arts Council subsequently lent this cast to Leeds City Art Gallery and, after having been placed in the grounds of Temple Newsam House, was vandalized there in early November 1953. In 1956 it was removed from public view before being loaned to the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art in 1961. Its ownership was later transferred to the Scottish Arts Council, which presented it to the National Galleries of Scotland in 1969. Another bronze cast is housed in the collection of the Musée national d’art moderne, Paris, and other examples from the edition are believed to be held in private collections. In February 2012 one of these was sold at Christie’s, London, for £19.1 million, which was a record price for a bronze sculpture by Henry Moore. See Colin Gleadell, ‘Modern Sales Review: When Moore Means More’, Daily Telegraph, 13 February 2012, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/art/artsales/9080076/Modern-sales-review-when-Moore-means-more.html , accessed 13 January 2014.

Prior to making Reclining Figure the only other plaster sculpture Moore had made on a large scale was Family Group 1948–9.

David Mitchinson, ‘A Note on the Plasters’, in Claude Allemand-Cosneau, Manfred Fath and David Mitchinson (eds.), Henry Moore From the Inside Out: Plasters, Carvings and Drawings, Munich 1996, p.59.

Margaret McLeod, letter to Richard Calvocoressi, 18 August 1980, Tate Artist Catalogue File, Henry Moore, A23946.

Henry Moore cited in J.D. Morse, ‘Henry Moore Comes to America’, Magazine of Art, vol.40, no.3, March 1947, pp.97–101, reprinted in Philip James (ed.), Henry Moore on Sculpture, London 1966, p.264.

Henry Moore, ‘A Sculptor Speaks’, Listener, 18 August 1937, pp.338–40, reprinted in Alan Wilkinson (ed.), Henry Moore: Writings and Conversations, Aldershott 2002, p.194.

Rudolf Arnheim, ‘The Holes of Henry Moore: On the Function of Space in Sculpture’, Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, vol.7, no.1, September 1948, pp.29–38.

Elizabeth Brown, ‘Moore Looking: Photography and the Presentation of Sculpture’, in Dorothy Kosinski (ed.), Henry Moore: Sculpting the 20th Century, exhibition catalogue, Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas 2001, p.294.

Richard Cork, ‘An Art of the Open Air’, in Susan Compton (ed.), Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Royal Academy of Arts, London 1988, p.20.

Anon., ‘Leeds Gets Monstrosity: Reclining Figure, the Storm Bursts in Yorks’, Yorkshire Evening Post, 8 November 1951, cited in Berthoud 2003, p.272.

Henry Moore, ‘Sculpture in the Open Air: A Talk by Henry Moore on his Sculpture and its Placing in Open-Air Sites’, ed. by Robert Melville, London 1955, reprinted in Philip James (ed.), Henry Moore on Sculpture, London 1966, p.101.

Arie Hartog, ‘The Centre of Modern Sculpture: Some Thoughts on Hepworth and Moore’ in Penelope Curtis and Keith Wilson (eds.), Modern British Sculpture, Royal Academy, London 2011, pp.156–7.

For this image see http://punch.photoshelter.com/image/I0000zfvqvF7AluU , accessed 10 January 2014.

For the exhibition catalogue accompanying Moore’s exhibitions in Canada and New Zealand see http://www.aucklandartgallery.com/media/166376/cat9.pdf , accessed 13 January 2014.

Mark Stocker, ‘The Best Thing Ever Seen in New Zealand: The Henry Moore Exhibition of 1956–57’, Sculpture Journal, vol.16, no.1, 2007, p.88.

Katarzyna Murawska-Muthesius, ‘Dreams of the Sleeping Beauty: Henry Moore in Polish Art Criticism and Media, Post-1945’ in Jane Beckett and Fiona Russell, Henry Moore: Critical Essays, Leeds 2003, pp.195–220.

Our Art Critic [David Thompson], ‘Mr. Henry Moore’s Exhilarating Exhibition’, Times, 28 November 1960, p.6.

Alice Correia, ‘Reclining Figure: Festival’, in Penelope Curtis (ed.), Tate Britain Companion Guide, London 2013, p.166.

Related essays

- Henry Moore: The Plasters Anita Feldman

- Henry Moore and the Welfare State Dawn Pereira

Related catalogue entries

Related material

-

Photograph

-

Photograph

-

Photograph

How to cite

Alice Correia, ‘Reclining Figure 1951 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, January 2014, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www