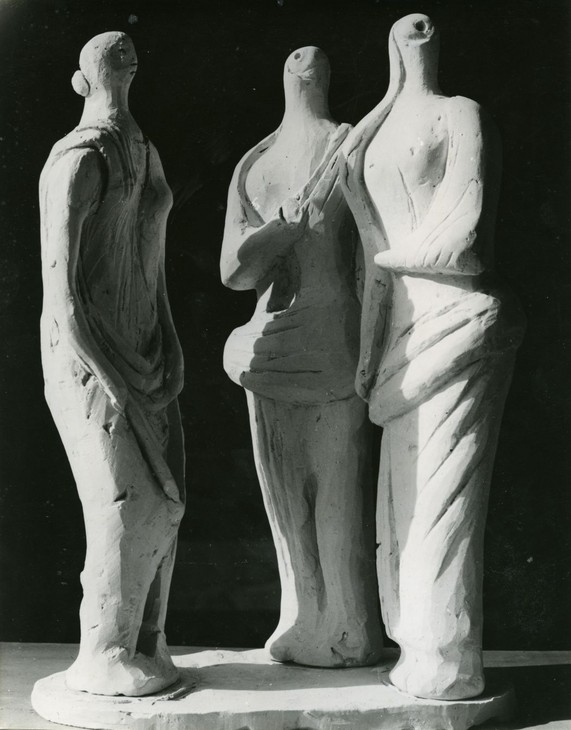

Henry Moore OM, CH Three Standing Figures 1945, cast c.1945-51

Image 1 of 12

-

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Standing Figures 1945, cast c.1945-51© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Standing Figures 1945, cast c.1945-51© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Standing Figures 1945, cast c.1945-51© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Standing Figures 1945, cast c.1945-51© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Standing Figures 1945, cast c.1945-51© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Standing Figures 1945, cast c.1945-51© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Standing Figures 1945, cast c.1945-51© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Standing Figures 1945, cast c.1945-51© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Standing Figures 1945, cast c.1945-51© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Standing Figures 1945, cast c.1945-51© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Standing Figures 1945, cast c.1945-51© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Standing Figures 1945, cast c.1945-51© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Standing Figures 1945, cast c.1945-51© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Standing Figures 1945, cast c.1945-51© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Standing Figures 1945, cast c.1945-51© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Standing Figures 1945, cast c.1945-51© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Standing Figures 1945, cast c.1945-51© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Standing Figures 1945, cast c.1945-51© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Standing Figures 1945, cast c.1945-51© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Standing Figures 1945, cast c.1945-51© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Standing Figures 1945, cast c.1945-51© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Standing Figures 1945, cast c.1945-51© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Standing Figures 1945, cast c.1945-51© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Standing Figures 1945, cast c.1945-51© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH,

Three Standing Figures

1945, cast c.1945-51

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Three Standing Figures is a plaster maquette for the larger stone version of the sculpture in Battersea Park, London. While the poses and drapery of the figures allude to the subjects and forms of ancient classical art, the origins of the sculpture lie in Moore’s Shelter Drawings made during the Second World War, which has led critics to consider it as a representation of anxiety or watchfulness.

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Three Standing Figures

1945, cast c.1945–51

Plaster

230 x 116 x 102 mm

Lent from a private collection 1994

L01768

Three Standing Figures

1945, cast c.1945–51

Plaster

230 x 116 x 102 mm

Lent from a private collection 1994

L01768

Ownership history

Acquired directly from the artist by the artist’s sister, Mrs Mary Spencer Garrould, Norfolk, c.1951, thence by descent; lent from a private collection in 1994.

Exhibition history

1968

?Henry Moore, Tate Gallery, London, July–September 1968 (?another plaster exhibited no.67).

2004

Henry Moore at Dulwich Picture Gallery, Dulwich Picture Gallery, London, May–September 2004, no.97.

References

1945

Henry Moore, ‘Henry Moore: New Designs for Sculpture’, Horizon, vol.12, no.71, November 1945, pp.308–9 (terracotta maquette reproduced).

1948

Robert Melville, ‘Contemporary Sculpture in the Open Air’, Listener, 10 June 1948, pp.942–3.

1948

A.D.B. Sylvester, ‘The Evolution of Henry Moore’s Sculpture II’, Burlington Magazine, vol.90, no.544, July 1948, pp.189–95 (Three Standing Figures 1947–8 reproduced).

1948

Edith Hoffmann, ‘Sculpture at Battersea Park’, Burlington Magazine, vol.90, no.544, July 1948, pp.207–8.

1952

Herbert Read, The Philosophy of Modern Art, New York 1952 (Three Standing Figures 1947–8 reproduced no.12).

1955

George Wingfield Digby, Meaning and Symbol in Three Modern Artists: Henry Moore, Edvard Munch, Paul Nash, London 1955 (Three Standing Figures 1947–8 reproduced pl.28).

1959

Erich Neumann, The Archetypal World of Henry Moore, London 1959, pp.94–7 (Three Standing Figures 1947–8 reproduced nos.64–5).

1960

Will Grohmann, The Art of Henry Moore, London 1960, pp.145–6.

1965

Herbert Read, Henry Moore: A Study of his Life and Work, London 1965 (Three Standing Figures 1947–8 reproduced pl.145).

1966

Philip James (ed.), Henry Moore on Sculpture, London 1966 (Three Standing Figures 1947–8 reproduced nos.28–9).

1968

John Hedgecoe (ed.), Henry Moore, London 1968, pp.167–9.

1968

John Russell, Henry Moore, London 1968, p.115 (Three Standing Figures 1947–8 reproduced pl.106).

1968

David Sylvester, Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1968, p.171.

1970

Robert Melville, Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings 1921–1969, London 1970, p.22 (Three Standing Figures 1947–8 reproduced pls.365–7).

1973

John Russell, Henry Moore, 1968, 2nd edn, London 1973, pp.135–6.

1977

David Finn, Henry Moore: Sculpture and Environment, New York 1977 (Three Standing Figures 1947–8 reproduced pp.233–9).

1978

Erich Steingräber, Henry Moore Maquetten, Munich 1978, pp.28–9.

1979

John Read, Portrait of an Artist: Henry Moore, London 1979 (Three Standing Figures 1947–8 reproduced pp.108–9).

1981

Henry Moore, Henry Moore at the British Museum, London 1981, pp.48–9.

1981

Richard Calvocoressi, ‘Public Sculpture in the 1950s’, in Sandy Nairne and Nicholas Serota (eds.), British Sculpture in the Twentieth Century, exhibition catalogue, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London 1981, pp.134–53.

1988

David Sylvester (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 1: Complete Sculpture 1921–8, 1957, 5th edn, London 1988, no.258.

1992

Julian Stallabrass, ‘Henry Moore: Mother and Child’, in Henry Moore: Mutter und Kind / Mother and Child, exhibition catalogue, Käthe Kollwitz Museum, Cologne 1992, http://www.courtauld.ac.uk/people/stallabrass_julian/PDF/Moore.pdf, accessed 13 December 2013.

1996

Claude Allemand-Cosneau, Manfred Fath and David Mitchinson (eds.), Henry Moore From the Inside Out: Plasters, Carvings and Drawings, Munich 1996, pp.116–17.

1998

Henry Moore 1898–1986: Eine Retrospektive zum 100 Geburtstag, exhibition catalogue, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna 1998 (another plaster reproduced p.230).

2000

Henry Moore: In the Light of Greece, exhibition catalogue, Basil and Elise Goulandris Foundation Museum of Contemporary Art, Andros 2000, p.155 (another plaster reproduced).

2003

Robert Burstow, ‘Henry Moore’s “Open-Air” Sculpture: A Modern, Reforming Aesthetic of Sunlight and Air’, in Jane Beckett and Fiona Russell (eds.), Henry Moore: Critical Essays, Aldershot 2003, pp.143–72 (Three Standing Figures 1947–8 reproduced p.146).

2004

Henry Moore at Dulwich Picture Gallery, exhibition catalogue, Dulwich Picture Gallery, London 2004, reproduced p.169.

2006

Christa Lichtenstern, ‘Three Standing Figures’, in David Mitchinson (ed.), Celebrating Moore: Works from the Collection of the Henry Moore Foundation, London 2006, pp.212–13.

2006

Robert Burstow, ‘Modern Sculpture in the Public Park: A Socialist Experiment in Open Air “Leisured Culture”’, in Patrick Eyres and Fiona Russell (eds.), Sculpture and the Garden, London 2006, pp.133–44.

2007

Jeremy Lewison, Henry Moore 1898–1986, Cologne 2007 (Three Standing Figures 1947–8 reproduced p.55).

2008

Christa Lichtenstern, Henry Moore: Work-Theory-Impact, London 2008, pp.137–40.

2011

Anita Feldman and Malcolm Woodward, Henry Moore: Plasters, London 2011 (another plaster maquette reproduced no.52).

Technique and condition

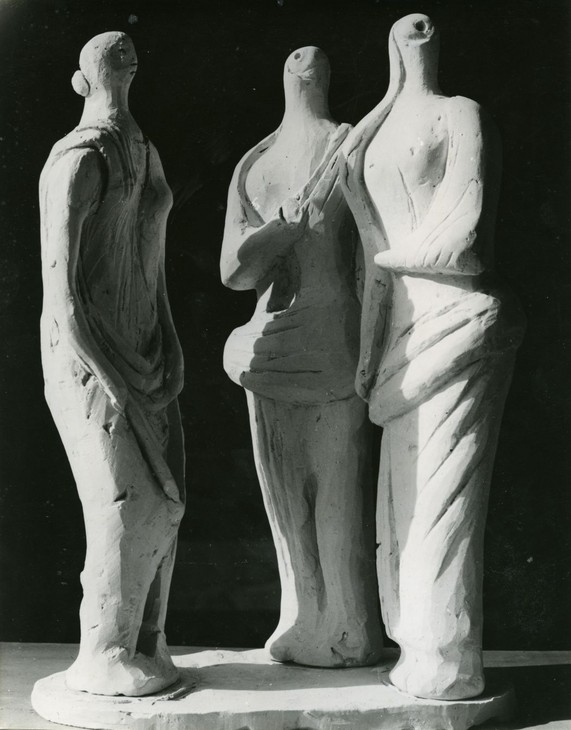

Henry Moore

Three Standing Figures 1945

Terracotta

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.1

Henry Moore

Three Standing Figures 1945

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

This sculpture comprises three standing figures in draped clothing arranged in a semi-circular formation on a rectangular base. It is made of plaster and was probably cast from an original clay model (fig.1). It is likely that the plaster figures were cast separately before being inserted into the base. This is supported by the existence of two clay slip figures held at the Henry Moore Foundation which have plugs at their feet. Marks on the base suggest that the plaster was smoothed with a spatula, possibly after the figures were inserted.

Detail of repair on Three Standing Figures 1945, cast c.1945–51

L01768

On long-term loan to Tate L01768

On long-term loan to Tate L01768

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Detail of repair on Three Standing Figures 1945, cast c.1945–51

L01768

On long-term loan to Tate L01768

On long-term loan to Tate L01768

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of casting bubbles on Three Standing Figures 1945, cast c.1945–51

L01768

On long-term loan to Tate L01768

On long-term loan to Tate L01768

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Detail of casting bubbles on Three Standing Figures 1945, cast c.1945–51

L01768

On long-term loan to Tate L01768

On long-term loan to Tate L01768

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The surface of the sculpture does not appear to have been worked on after casting but some repairs and alterations are visible. For example, all three figures appear to have been broken at the ankle at some point, the repairs for which were made with new plaster (fig.2). Other repairs are particularly visible on the rear of the central and left-hand figures below the knees. Fine cracks can be seen in the necks of all three figures. Casting seams can be detected on the sides and heads of the figures but these have been removed with a fine file. Casting bubbles can also be seen in some areas (fig.3). Later applications of plaster on the front of the skirt and left hip are visible on the right-hand figure, but it is not known when these repairs and alterations were carried out.

After casting the plaster surface was coloured with thin layers of pinkish-brown pigment. This suggests that Moore intended the work to be regarded as a sculpture in its own right, rather than as a working model. There is no signature on this sculpture.

Lyndsey Morgan

March 2011

How to cite

Lyndsey Morgan, 'Technique and Condition', March 2011, in Alice Correia, ‘Three Standing Figures 1945, cast c.1945–51 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, January 2014, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://wwwEntry

Henry Moore

Three Standing Figures 1945, cast c.1945–51

L01768

On long-term loan to Tate L01768

On long-term loan to Tate L01768

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

Henry Moore

Three Standing Figures 1945, cast c.1945–51

L01768

On long-term loan to Tate L01768

On long-term loan to Tate L01768

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The left-hand figure has lightly defined facial features and a bun of hair is positioned at the nape of her neck. She wears a long sleeveless tunic which is gathered in front of her navel and thighs. Her left arm is held against the side of her body, while a gap is discernable between her body and her right arm. She stands in a seemingly unnatural position with both knees bent, in contrast to the central figure, who appears to stand contrapposto with her left knee bent and the right leg straight. This figure appears to be wearing a long-sleeved cloak, open at the chest and the right shoulder. A large bundle of fabric wraps the circumference of her body around the hips. Her right elbow is bent and her forearm is positioned on her chest, holding the drapery across her breasts. Three vertical lines suggest drapery on the rear of the figure’s legs, while the only feature on the face is a single circular impression, which may represent an eye. The figure on the right shares this same single physiognomic feature, which suggests that although her body is facing inwards, she is looking out to her left. This figure’s right arm hangs by her side while her left arm, which appears to be in a sling, is positioned horizontally across her waist. A swathe of fabric wraps around her body on a diagonal, from the left hip down to the right thigh.

In 1948 the art critic David Sylvester identified specific differences between the figure on the left and the two figures standing closer together on the right. For Sylvester, the figure on the left was ‘the naturalistic member of the Three Standing Figures [who] expresses a simple, though subtle, womanly emotion, whereas the two other figures, whose style is anti-naturalistic and multi-evocative, are hermaphroditic in form and in content a mysterious, ambiguous, complex of conflicting emotions’.2 Similarly, in 1960, the art historian Will Grohmann described the full-size stone version, for which this work was a maquette, as follows:

The left-hand figure is unquestionably the most human and naturalistic, her face is visible, while the other two wear a veil that leaves only the upper part of the face uncovered. Her garment hangs loosely from her shoulders and falls in unobtrusive folds over her abdomen and knees, her arms hang limp. The way in which the drapery is swathed round the hips of the other two gives them a more obtrusively costumed appearance, while their arms are held in more conscious poses. All three have something of the prophetess about them: they gaze into infinite distance, without betraying either boon or bane in their facial expression. They stand above things, are beings of a human kind, but not of this world, mysterious creatures, ‘neither frightful nor deadly in their magnificence’, neutral characters and strangely ambivalent in appearance.3

In 1965, discussing the large stone version of Three Standing Figures, the critic Herbert Read identified ‘a strongly emphasised rhythmical treatment of the human figure, and a convincing solution of the problem of relating three upright figures to each other and to an overriding plastic unity’.4 Of particular interest to Read was Moore’s stylisation of the heads of the two figures on the right: ‘they become periscopic organs, total eyes that range the infinite space around them’.5

Origins and facture

Three Standing Figures was Moore’s first attempt at presenting a group of standing women in sculptural form. Moore’s plans for the sculpture can be traced to his earlier Shelter Drawings, made in 1941–2, which depict women and children taking refuge in the London Underground during the Blitz. Swathed and draped in blankets, these figures – depicted standing, sitting and reclining – expressed the collective anxiety felt by those who lived through the Second World War.6 In 1955 Moore confirmed the link between the drawings and the sculpture, stating that in making Three Standing Figures he sought to convey ‘the group feeling that I was concerned with in the shelter drawings’.7

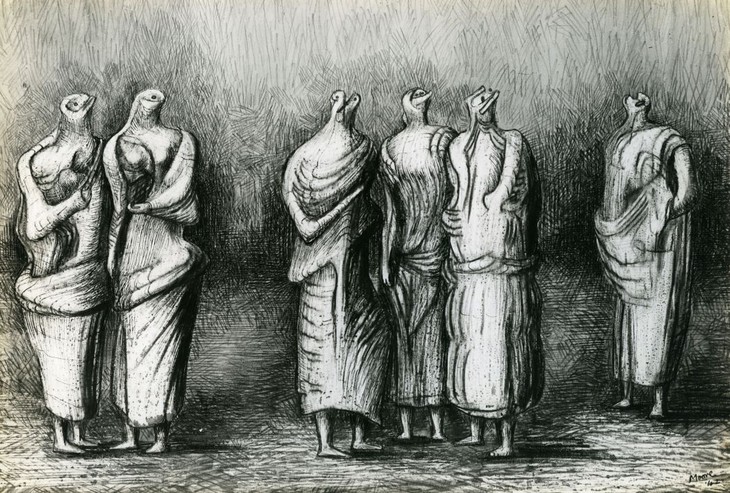

Henry Moore

Group of Draped Standing Figures 1942

Graphite, wax crayon, coloured crayon, wash, pen and ink on paper

391 x 565 mm

The Art Institute of Chicago

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Michel Muller, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.2

Henry Moore

Group of Draped Standing Figures 1942

The Art Institute of Chicago

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Michel Muller, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Henry Moore

Draped Standing Figures in Red 1944

Graphite, wax crayon, watercolour, pen and ink on paper

400 x 311 mm

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Henry Moore

Draped Standing Figures in Red 1944

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

In 1974 the art historian Kenneth Clark identified a series of drawings made between 1942 and 1946 in which the composition of Three Standing Figures was seemingly developed. He argued that although they clearly developed from the Shelter Drawings, in this new body of work Moore chose to isolate the figures from any specific context. While Clark acknowledged that he ‘did not know the exact sequence of these drawings’, he nonetheless proposed that Group of Draped Standing Figures 1942 (fig.2) was the ‘crucial drawing’, noting that the cluster of three women in the centre of the page not only anticipated Moore’s sculpture, but that ‘the two figures to the left [of the page] are almost exactly as they were to be used, five years later’.8

It is evident from drawings such as Draped Standing Figures in Red 1944 (fig.3) that as well as considering the individual poses of each woman, Moore also grappled with the arrangement of his three figures. Indeed, the way in which the pair of women interacted with the third was clearly still under consideration in 1944. As Moore noted in 1955, ‘although the problem of relating separate sculptural units was not new to me, my previous experience of the problem had involved more abstract forms; the bringing together of these three figures involved the creation of a unified human mood’.9 Clark suggested that in his two-dimensional sketches, Moore ‘never quite arrives at the final solution, in which the left-hand figure is passive and motherly, without the nervous tension of her companions’.10

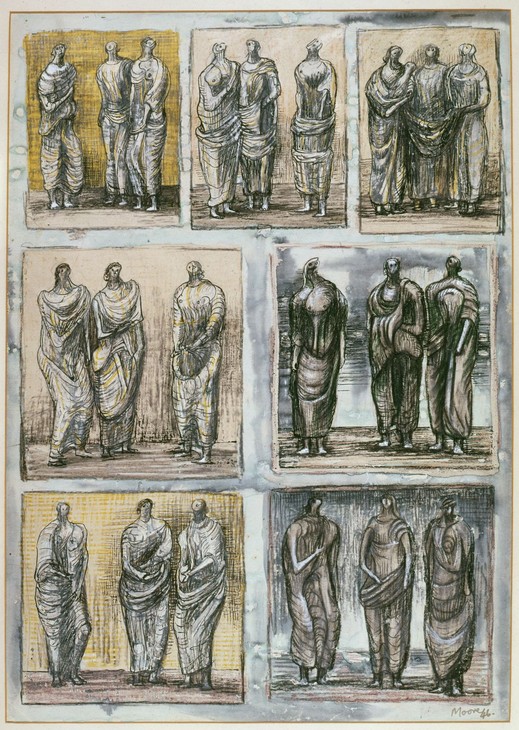

Henry Moore

Studies of Three Standing Figures 1946

Graphite, wax crayon, coloured crayon, watercolour wash, pen and ink and gouache on paper

375 x 277 mm

The Trustees of Lord Walston's Family Trust

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.4

Henry Moore

Studies of Three Standing Figures 1946

The Trustees of Lord Walston's Family Trust

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Henry Moore

Three Standing Figures 1945

Terracotta

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.5

Henry Moore

Three Standing Figures 1945

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

According to Clark, Moore was only able to solve the problem of how to relate each figure to the other by making three-dimensional terracotta models. It was at this point, Clark argued, that the role of the left-hand figure became clear: ‘she is the shock-absorber and the potential comforter, who gives the group, when realised in stone, its monumental character’.11 Clark claimed that the terracotta was made in 1947, which served to legitimise his argument that the model evolved from the sequence of drawings he identified, which he proposed culminated in a sheet of sketches presenting seven arrangements of three standing figures that is signed by the artist and dated 1946 (fig.4).12 The drawing on the bottom left of this page is closest to the final configuration, although the two women on the right do not possess the same stylised forms or periscopic faces of the figures in the final sculpture. However, Moore’s catalogue raisonné published in 1957 dated the terracotta to 1945 and two photographs of the sculpture were published in the journal Horizon in November 1945 (fig.5). This indicates that Studies of Three Standing Figures was made after the terracotta, demonstrating that Moore continued to experiment with the configuration of the figures in two dimensions even after working in three.

In 1948 David Sylvester noted that the terracotta original ‘has been cast most suitably, not in metal but in plaster’.13 Although it is possible that Moore cast multiple copies of the sculpture in plaster, only two versions are known to exist: one is held at Tate and the other at the Henry Moore Foundation. This other version presents the three figures on an oval base and has a cream-brown colour. Significantly, this plaster also has pencil markings on its surface which suggest that it was used as the template when Moore enlarged the sculpture in stone in 1947–9.

Detail of casting bubbles on Three Standing Figures 1945, cast c.1945–51

L01768

On long-term loan to Tate L01768

On long-term loan to Tate L01768

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.6

Detail of casting bubbles on Three Standing Figures 1945, cast c.1945–51

L01768

On long-term loan to Tate L01768

On long-term loan to Tate L01768

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Three Standing Figures 1945, c.1945–51 on a shelf in Moore's studio c.1951

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.7

Henry Moore

Three Standing Figures 1945, c.1945–51 on a shelf in Moore's studio c.1951

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Air bubbles and casting seams on Tate’s plaster indicate that it was cast from a mould, rather than built up over an armature (fig.6). Each figure appears to have been cast separately before being mounted onto the rectangular cuboid base. After casting the figures were finished with files to remove unwanted spurs or seam ridges. The plaster was also coloured with a thin layer of pink-brown pigment suggesting that this version of the sculpture was regarded as an artwork in its own right rather than as a preliminary model. A photograph dated c.1951 shows Tate’s plaster on a shelf in Moore’s studio surrounded by other maquettes, which indicates that it was cast some time between 1945 and c.1951 (fig.7).

The whereabouts of the original terracotta model are unknown. However, two figures made in clay slip are held in the collection of the Henry Moore Foundation. Clay slip is liquid clay that is poured into a mould to create a sculpture. It seems likely that a mould was made from the terracotta original in order to cast the clay slip versions, although it is not known when this took place.

Three Standing Figures also exists in a bronze edition of four plus one artist’s copy, cast between 1948 and 1949. Having made the decision to cast the sculpture in bronze, it would have been important to keep plaster or clay casts of the design in case the mould was damaged or the original destroyed at the foundry. Moore used two different foundries to cast the bronze edition: Fiorini in London made the first cast and Alexis Rudier Fondeur in Paris made the four additional casts. Examples of these sculptures are held in the Smith College Museum of Art, Massachusetts and the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice. An additional artist’s cast was made in 1985 by Maurice Singer foundry, London, and is held in the collection of the Henry Moore Foundation. The bronze figures are mounted on a rectangular base, as opposed to an oval one, which suggests that they were either cast from Tate’s plaster, or that Tate’s plaster cast was taken from the same mould used to create the bronze edition.

In 1947 Moore started the process of enlarging his small model for Three Standing Figures to a scale over life-size. This work was undertaken outside Moore’s studio at his home, Hoglands, in Hertfordshire, with the help of his assistants Bernard Meadows, Shelly Fausset, Leslie Lawley and Reg Butler. The sculpture was one of Moore’s last carvings made in an English stone – Darley Dale sandstone – and was carved between August 1947 and May 1948. The finished full-size sculpture was first exhibited in the 1948 Open Air Exhibition of Sculpture at Battersea Park, London, organised by London County Council in association with the Arts Council of Great Britain, after which it was bought by the Contemporary Art Society and sited permanently in the park.

Context and interpretation

Noting the origins of Three Standing Figures in Moore’s wartime drawings, the art historian Roger Cardinal remarked in 2000, ‘broadly speaking, wartime compelled him [Moore] to define his role as a public figure responsive to public needs: like many contemporary artists, he found himself turning to themes of a humanistic and traditional type’.14 In line with his public responsibility as a war artist, which required him to make work that would be comprehensible to a broad population, Moore made a pronounced return to figuration in the immediate post-war period. The first sculptures he made after the war thus represented a departure from his more abstract, surrealist inspired experiments of the 1930s, exemplified by Stringed Figure 1938, cast 1960 (Tate T00386). In 1955 Moore expanded on the relationship between his wartime drawings and Three Standing Figures, noting that,

the pervading theme of the shelter drawings was the group sense of communion in apprehension. But I only wanted a hint of that mood to remain in the three figures. I wanted to overlay it with the sense of release, and create figures conscious of being in the open air; they have a lifted gaze, for scanning distances.15

Henry Moore

The Three Fates 1948

Graphite, charcoal, wax crayon, coloured crayon, watercolour, wash, pen and ink on paper

400 x 585 mm

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Michael Phipps, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.8

Henry Moore

The Three Fates 1948

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Michael Phipps, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Moore’s turn to classical subjects and forms in the post-war period was not unique, and it is significant that photographs of his terracotta maquette were published in the journal Horizon in 1945 in conjunction with an essay by Thierry Maulnier titled ‘Towards a New Classicism’.18 Maulnier suggested that ‘classicism can provide the noble satisfactions arising from a union between the tragedy of human destiny and its perfect expression in words, whereby the tragedy is fully realised – and splendidly surpassed’.19 While Maulnier’s concern was with French literature, Moore’s terracotta Three Standing Figures presented a visual example of this modern classical idiom.

Most interpretations of Three Standing Figures have focused on the large-scale stone version. Although the Battersea Park sculpture is smoother and more stylised than the smaller plaster versions, responses to it remain useful for understanding Tate’s plaster cast. In his 1948 essay published in the Burlington Magazine Sylvester gave an idiosyncratic interpretation of the sculpture, suggesting that it may be read as a family group: the protective mother, the stern father, and the child on the far right, who looks out into the future. For Sylvester, the success of the sculpture was the way in which ‘we are left in doubt whether it [the right-hand figure] is anxious to break away from the group or whether seeking refuge within the family from outside terror’.20 This sense of uncertainty was also identified by the critic George Wingfield Digby in his 1955 book Meaning and Symbol in Three Modern Artists. He stated that:

the monumental group of ‘Three Standing Figures’ in Battersea Park is not macabre ... but it is none the less challenging and disturbing ... These beings with their stunted heads, remote and undifferentiated expressions, their unwieldy antediluvian forms, are the very antithesis of modern man. Personality, character, intellectual power, individual adaptation to the social and cultural heritage, these figures show none of this. They partake of another world foreign to ours and remote from our twentieth century life.21

In contrast, in 1959 the psychologist Erich Neumann identified the sculpture as an exemplary manifestation of Moore’s preoccupation with the archetype of the ‘Earth Mother’, arguing that:

here the spiritual core of the feminine archetype has been reached and shaped in stone, a numinous center that stands, solid and unshakable, on the earth and amidst its trees, and yet is inaccessibly strange, infinitely surpassing and looking beyond this world. For all their rootedness in earth and their human shape, the figures are turned entirely elsewhere; their gaze is directed into the far distance, augurs of some ‘supercelestial place’ with whose observation they seem to be entrusted. They have the rocklike dependability of the Great mother, but their steadfastness includes death and disaster as well as life and its duration. The bond between the three figures as they gaze so intently into the future is so strong that despite their individual differences they have the effect of a unity. In them life and death are transcended, and out of these opposites they produce a third – be it called Fate or Meaning – arises from the interplay of black and white, life and death, past and future, as a fulfillment of the present, a higher reality of being.22

In 1968 the critic John Russell identified Moore’s standing figures as ‘watchers’, noting that the subject of witnessing had been a preoccupation of the poet W.H. Auden in the 1930s, and was further explored in the post-war period by the sculptors Reg Butler and Lynn Chadwick (see Tate N05942 and T01226 respectively). Russell suggested that, ‘the man or woman who watches the skies has a particular emotional meaning for anyone who, from the Spanish Civil War onwards, has looked on the skies primarily as a potential source of catastrophe, and in carving this group Moore drew, whether consciously or not, on the stored memories of millions. This gives the group a distinct historical importance’.23 Concurrently in 1968, Moore acknowledged that ‘it is as though the three women are standing there, expecting something to happen from the sky ... Maybe this wasn’t done consciously. You don’t always do things consciously. I don’t anyhow’.24 By the 1970s, commentators including the critic Robert Melville regarded the work in terms of its post-war context. Melville argued that the sculpture ‘pays tribute to the women of the deep shelters by celebrating their return from the underworld ... They stand in a rough semi-circle, gazing at the sky. They drink in the light and air, but they are watchful, as if they have not yet lost the habit of scanning the sky for hostile aircraft’.25

Despite the small size of the plaster Three Standing Figures, Sylvester argued that ‘the expression of monumental feeling in a physically tiny form is manifest in the maquette ... Dramatically, it is not a whit less impressive than the stone group ... the immediate emotional impact of these miniature totems which are the maquette is, if anything, more powerful than that of the carved group’.26 Similarly, in 1960, Grohmann asserted that ‘in spite of its smallness, the terracotta model looks both monumental and mobile; the modelling is sketchy, but completely to the point, and the casualness of the detail bears the stamp of genius’.27

Three Standing Figures was acquired by Moore’s sister Mary Spencer Garrould, who lived in Norfolk, probably shortly after its creation. It remains in a private collection and has been on loan to Tate since 1994.

Alice Correia

January 2014

Notes

This sculpture is identified with the number 258 in the artist’s catalogue raisonné. See David Sylvester (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 1: Complete Sculpture 1921–48, 1957, revised edn, London 1988, p.164. Although only the original terracotta and a bronze edition are listed in this volume, the two existing plaster casts are also identified with this number in Anita Feldman and Malcolm Woodward, Henry Moore: Plasters, London 2011, pp.50–1.

A.D.B. Sylvester, ‘The Evolution of Henry Moore’s Sculpture II’, Burlington Magazine, vol.90, no.544, July 1948, p.190.

For more on the Shelter Drawings see Andrew Causey, The Drawings of Henry Moore, London 2010, p.114.

Henry Moore, ‘Sculpture in the Open Air – A Talk by Henry Moore on his Sculpture and its Placing in Open-Air Sites’, March 1955, reprinted in Philip James (ed.), Henry Moore on Sculpture, London 1966, pp.103, 108.

Roger Cardinal, ‘Henry Moore: In the Light of Greece’, in Henry Moore: In the Light of Greece, exhibition catalogue, Basil and Elise Goulandris Foundation Museum of Contemporary Art, Andros 2000, pp.28–9.

Related essays

- Scale at Any Size: Henry Moore and Scaling Up Rachel Wells

- Ambivalence and Ambiguity: David Sylvester on Henry Moore Martin Hammer

- Henry Moore: The Plasters Anita Feldman

- ‘Worthy of the great tradition’: Kenneth Clark on Henry Moore Chris Stephens

Related catalogue entries

Related material

How to cite

Alice Correia, ‘Three Standing Figures 1945, cast c.1945–51 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, January 2014, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www