Four concentric circles of different colours are centred on a square canvas, constituting an apparently unequivocal expression of the power of pure abstraction. But as much as Noland’s Gift 1961–2 (Tate T00898) might appear to deny references to the outside world, its form also suggests – perhaps even produces – powerful bodily sensations. Painted at a scale that looms over the viewer, its radiating circles appear to vibrate and pulse across an immense field of warm colour. The energy appears to originate at the centre of the work and radiate outwards, an effect of the composition. ‘I always had a tendency to center’, Noland recalled in an interview towards the end of his life. ‘There’s something about the centering that keeps me focused’.1 This focus on the centre unites much of Noland’s oeuvre. Whether painting circles, chevrons, stripes or plaids, his compositions are balanced, typically symmetrical, and have a clear focal point. The painted fields, and the energy they evoke, consistently radiate from a single point of origin.

This chapter addresses Noland’s obsession with centrality and balance, reading it through the artist’s experience of the intensive psychoanalytic therapy developed by Wilhelm Reich. This analysis will expand the theoretical context in which Noland’s paintings have thus far been understood, as well as point to the potential of painting to represent, if not simulate, Reich’s theories. Although now often dismissed due to his controversial ideas regarding sex, science, and the connection between sexual repression and neurotic behaviour, Reich’s particular approach to psychology had currency in 1950s and 1960s America. Not only did Noland undertake Reichian therapy at this time, but other artists and intellectuals including Allen Ginsberg, Paul Goodman, J.D. Salinger, Norman Mailer and William Burroughs were all also influenced by his writings.

A student of Sigmund Freud, Reich worked in Freud’s Psychoanalysis Polyclinic in Vienna before moving to the United States in 1939 after a conflict with his teacher. In America Reich taught courses at the New School for Social Research in Manhattan. In contrast to Freud’s focus on the unconscious, Reich developed a theory dependent on the body and its relationship to the surrounding world. His theories resonated with the post-war crisis in subjectivity, which he suggested was a result of an imbalance of a universal biologic energy within human and atmospheric systems. Reich’s holistic approach, centred on the belief that all organic matter responds to the same environmental factors, had a profound impact on American culture and continues to represent an important contribution to the history of psychology.2

The fundamental component of Reich’s theory is orgone, an ‘energy, which is capable of charging organic matter’.3 According to Reich, orgone must flow freely through the body for stable mental and physical health; when orgone is blocked, the body experiences physical discomfort and neurotic behaviour. Energy flow can also be inhibited by layers of ‘character armour’ that develop internally over the course of life and in response to traumatic events.4 For Reich, character armour materialises as seven segments or rings: ocular, oral, deep neck, chest, diaphragm, back, and pelvic.5 Unlike other therapeutic models, such as Freud’s talking cure, Reich’s treatment demanded intense bodily activity. To break down armour at the ocular level, for instance, the patient opened and closed their eyes very wide and made deep frowns and grins.6 The oral and deep neck levels required forced vomiting; the chest and diaphragm, deep breathing exercises; while work on the back ring entailed focused relaxation and loosening of muscles to allow orgone flow.7 Reich believed that the pelvic ring suffered most. Gastrointestinal disorders such as uterine polyps and general inflammation were due to pelvic tension and character armour.8 To break down this final layer, strenuous kicking movements or deep massages were prescribed.9 Describing the therapeutic process in 1970, Ellsworth Baker, a prominent Reichian doctor in New York, stated: ‘the hard emotions have to come out first … the rage and the fury and the hate. Only when they’re released can you get through to the tender feelings – the love and longing and sadness’.10 In this way both the intense physical and emotional aspects of Reichian therapy in order to facilitate orgone flow depend on the idea of opening up, creating channels for energy to flow and reach the centre or core of the system. It is this conceit of expansion and retraction, suggested by a radiating pulse of energy, which I want to read into the circular forms and bold colours of paintings such as Gift.

Noland’s early encounters with Reich’s theories came from Robin Bond, Director of Art Studies at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Washington, D.C., where Noland enrolled as a student-teacher in 1949.11 Bond and Noland discussed Reich’s major published works, The Discovery of Orgone (1942), Character Analysis (1945) and The Mass Psychology of Fascism (1946), and it was Bond who, in 1950, recommended that Noland and his wife, the artist Cornelia Langer, try Reichian therapy with Dr Charles I. Oller in Philadelphia.12 From then on Noland’s interest in Reich only grew; he visited a Reichian therapist throughout his life and even subscribed to publications devoted to Reich.13 While the artist was often hesitant to discuss his interest in Reichian therapy, in an oral history interview with Paul Cummings in 1971 Noland reflected on the impact of Reich’s methods: ‘It had a great deal of significance on my life, on my work’, he explained. ‘In opening me up personally. I mean opening up a lot of my perceptions and a lot of my feelings, and as a consequence, what I do’.14 In 2007, towards the end of his life, he reinforced the significance of Reich during an interview with Dr Richard Schwartzman for the Journal of Orgonomy. One of Schwartzman’s concluding questions was ‘Who were the most important influences in your life?’ Noland responded: ‘There were different people, but Wilhelm Reich affected my life more than any other.’15

Fig.1

Kenneth Noland

Beginning 1958

Acrylic on canvas

2286 x 2435 mm

Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C.

© Kenneth Noland

It was in the midst of his commitment to Reich’s techniques that Noland arrived at the circle composition. The earliest circle paintings, which date from the late 1950s, often feature an outer circle of gestural paint splatters radiating around inner hard-edged circles. Beginning 1958, for example, is composed of approximately eleven concentric circles (fig.1).16 While the inner circles remain bound at their edges, the outer black circle extends towards the outer reaches of the canvas. The thinned paint is soaked directly into the fibres of the unprimed canvas, while the splatter whirls around the centre in a mesmerising rotation, as if energising its otherwise flat surface. This activation of the picture might allude to the softening of the rigid rings of armour in Reichian therapy. Noland’s discussion of his work relates to this sense of opening and activation: ‘I do open paintings. I like lightness, airiness, and the way colour pulsates. The presence of the painting is all that’s important’.17 The painting might even be said to emit energy akin to a beat or a pulse, as the circles expand and radiate across the space of the canvas. Its beating pulse, when perceived by the viewer, visualises the Reichian goal of attending to one’s own pulsing centre in order to connect with the flow of life in the world beyond.

Fig.2

Kenneth Noland

Breath 1959

Reproduced in Diane Waldman, Kenneth Noland: A Retrospective, 1977, p.122

Acrylic on canvas

Saint Louis Art Museum, Saint Louis

© Kenneth Noland

Colour was crucial to the pulsating properties of Noland’s circles. In addition to the teachings of Josef Albers and Ilya Bolotowsky, which he had encountered at Black Mountain College, Noland’s approach to colour owes much to Wassily Kandinsky, who had written at length about the ability of colour to recede and advance towards the viewer. For example, according to Kandinsky yellow expands away from the centre while blue recedes, while red has ‘a determined and powerful intensity. It glows in itself, maturely, and does not distribute its vigor aimlessly’.18 Kandinsky’s characterisation of colours expanding and contracting resonates with the effects of Noland’s circle paintings. These were effects that Noland understood in metaphysical terms: ‘colour has pulses, [and] those pulses can lead you from one dimension to another dimension … so that different colours have an accumulation of these pulses and give you a different kind of general resonance in a painting’.19 A painting such as Breath 1959 (fig.2), which was included in the Painting and Sculpture of a Decade exhibition at Tate in 1964, combines bright yellow, green and cool blue colours that together appear to pulse like the rhythmic rise and fall of a breathing body. While the inner rings appear contained and draw the eye in towards the centre, the outermost ring pulls the eye out towards the splatters at the edge of the canvas.

To further understand how Noland’s painting might be viewed in these terms, it is useful to compare a description of the experience of viewing Noland’s circles with a personal account of a Reichian patient undergoing treatment. In response to the works in Noland’s French and Company exhibition in 1959, critic Lawrence Campbell wrote that the ‘circles of colour radiating from a disk … seem to expand and contract, become dense and fluid at the same time … The paintings seem to be alive and breathing’.20 Campbell felt his review did not adequately describe ‘the sensations of pleasure one experiences in their [the paintings’] presence’.21 Campbell’s critical characterisation of his viewing experience may be compared to the description of television performer Orson Bean after a vigorous session with a doctor using Reich’s methods:

My thighs began to ache, and I wondered when he would say that I had done it long enough, but he didn’t. On and on I went until my legs were ready to drop off. Then, gradually, it didn’t hurt any more and that same sweet fuzzy sensation of pleasure began to spread through my whole body, only much stronger. I now felt as if rhythm had taken over my kicking which had nothing to do with any effort on my part. I felt transported and in the grip of something larger than me. I was breathing more deeply than I ever had before and I felt the sensation of each breath all the way down past my lungs and into my pelvis. Gradually, I felt myself lifted right out of Baker’s milk chocolate room and up into the spheres. I was breathing to an astral rhythm.22

This account of great physical exertion creating sensations that surge throughout the body, starting in the lungs and then moving down to the pelvis, the epicentre of the most fortified rings, demonstrates the effect of Reich’s therapy. Once character armour is gone, orgone pulses through the body, lifting it out of the physical world. The repetitive exercises and layers of armour that provided the core principles for Reich might be related to Noland’s concentric rings. Both the therapeutic exercise and the paintings generate waves of physical sensations that course through the body.

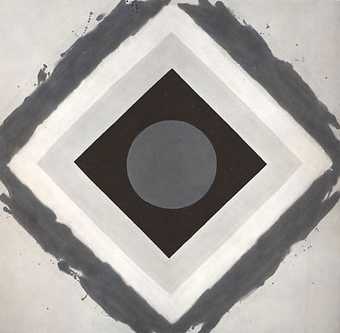

Fig.3

Kenneth Noland

Magic Box 1959

Acrylic on canvas

2362 x 2362 mm

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

© Kenneth Noland

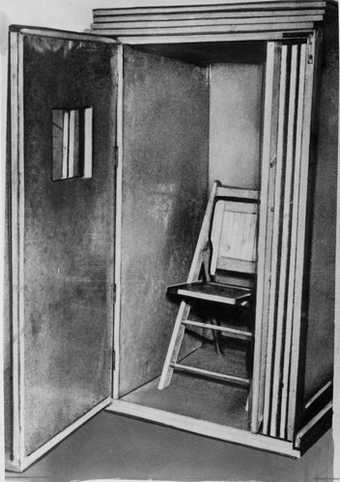

Fig.4

Orgone Accumulator 1960

Reproduced in the New York Times, 23 September 2011

Occasionally Noland made more explicit references to Reichian therapy. For example, the title of Magic Box 1959 (fig.3), a composition that features a red core surrounded by concentric squares, makes clear reference to Reich’s orgone accumulator (fig.4), a single-person enclosure invented by Reich to channel energy back into the body. About the size of a telephone booth and made of wood and metal, this seemingly ‘magical box’ contains a small chair for patients to sit on, and is filled with orgone for the patient to absorb intensively in a quiet, reflective state.23 The black-edged core of intense red in Noland’s painting could stand in for the patient inside the accumulator, while the strict attention to the centre, the radiating shapes and the contrasting colours are again suggestive of the movement of energy through the body in Reich’s psychology. Importantly, this painting, with its roughly hewn outermost square, is one of the few examples where the unbounded layer of energy appears to overflow the edge of the canvas, perhaps evoking the exceptional energy from this ‘magic box’.

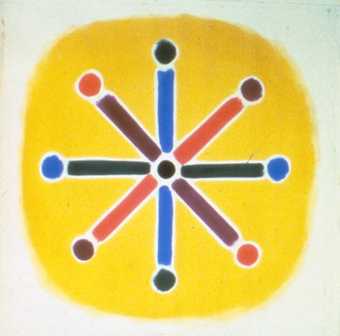

Fig.5

Kenneth Noland

Play 1960

Acrylic on canvas

1136 x 1108 mm

Private collection

© Kenneth Noland

Fig.6

Kenneth Noland

Back and Front 1960

Acrylic on canvas

1752 x 1752 mm

Private collection

© Kenneth Noland

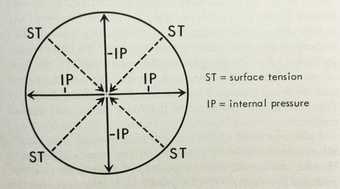

A more fundamental formal connection between Noland’s geometric compositions and Reich’s theories can be identified in the diagrams that Reich designed for his publications on orgone energy and therapy. Noland’s paintings Play 1960 (fig.5) and Back and Front 1960 (fig.6), for example, each have thick lines of paint that extend away from a central circle, rather than splatters that rotate around the core.24 These compositional arrangements recall a diagram by Reich showing what the body experiences when its armour prevents orgone from being released (fig.7). In the diagram the vectors represent the internal pressure that accumulates when orgone cannot pass through the armour. Although the linear elements in Back and Front appear to extend beyond the circle, which represents the problematic surface tension in Reich’s diagram, the vectors might be seen to push against the edges of the canvas, further implying a pulsing energy seething through the paint and fibres and across the surface of the flat canvas.25

Fig.7

‘Pressure from orgone inhibition’ in The Discovery of Orgone, Volume I: The Function of the Orgasm, New York 1973, p.261

As Noland worked on his circle paintings into the 1960s their compositions became increasingly bold and the previously splattered edge of the outer circle hardened. If the uneven quality of the outer edges might be read as an attempt to represent orgone energy, the later hard-edged paintings instead explored the potential of colour juxtaposition to visualise the physical feeling of orgone release. The neatly bounded edges in Gift are a good example of this. The intense cobalt blue ring appears to leap away from its neighbours – one tepid brown in colour, the other a cool bluish white. The palpable effects of the juxtapositions as well as the application of paint in different densities register a sense of movement across the surface, as if the canvas itself is imbued with a pulsing energy. These are the kind of effects that are lost in reproductions of Noland’s circles, subtleties drained out by the printed image that tends to encourage readings that do not sufficiently engage with the tactility of their effects, and I would suggest, the influence of Reich.

The vibrant composition of Gift not only focuses attention on the centre that Reichian therapy seeks to discover, but also on the very act of viewing a painting. In a sense, looking at works such as this might be understood as simulating a kind of therapy for the viewer or at least a mirroring of their own body, their own pulse.26 Prolonged looking may inspire the viewer to search for his or her own centre, to focus on the layers separating their inner core from the surrounding environment. The painting leads by example, encouraging the viewer to break down their armour and let the energy flow. It might even be argued that Noland’s paintings have the potential to facilitate Reichian therapy without the need for a psychoanalyst. The notion that Noland’s canvases might actually have an effect on the viewer’s bodily experience challenges other analyses of his paintings as cold and detached compositions that appeal only to the eye. This suggests an alternative way of reading paintings such as Gift, not as targets on which to direct disembodied vision, but as radiating forces enveloping the viewer from a central origin point.

The self-reflexivity implied in the search for an origin point corresponded with the antipathetic and nihilistic social-cultural mood that some writers and thinkers described in the aftermath of the Second World War. The Frankfurt School philosopher Theodor Adorno, for instance, wrote: ‘The idea that after this war life will continue “normally” or even that culture might be “rebuilt” – as if the rebuilding of culture were not already its negation – is idiotic.’27 There was a need for reflection and reparation, which tripped up the forward march of progress.

Reich blamed the rise of fascism in Europe on the suppression of sexuality and true biologic nature. He wrote, ‘It was the fascist deluge which swept across Germany like a tidal wave, astonishing everyone and causing many to ask how such a thing was possible’.28 He believed the problem stemmed from society’s increasing control of human behaviour through the quelling of unseemly acts:

The patriarchal, authoritarian era of human history has attempted to hold the asocial impulses in check by means of compulsive moralistic prohibitions … the biologic core of the human structure, is unconscious, and it is feared. It is at variance with every aspect of authoritarian education and control. At the same time, it is the only real hope man has of one day mastering social misery.29

In order to remedy the ‘social misery’ of the day, Reich claimed that ‘what is needed is the liberation and social protection of natural sexuality in the masses of the people … In fascism, only the reverse impulses have broken through. The post-fascist world will carry out the biological revolution which fascism did not produce but made necessary’.30 Reich’s identification of fascism as the culprit behind sexual oppression and neurotic behaviour was, at the time, a convincing argument. In the context of a world emerging from the threat of an extremism set to undermine free expression, Reich’s therapeutic regime not only provided a potential cure for the physical and mental traumas of war, but also suggested a route to heightened states of expression and mental capability through the body.

Fig.8

Wilhelm Reich

Swirl 1951

Oil on canvas

Wilhelm Reich Infant Trust, Rangeley

© Wilhelm Reich

The fact that Reich was an amateur painter is not irrelevant here. Indeed, it underscores the possibility that paintings could themselves hold therapeutic power within his practices. A year after Reich’s daughter gave him an oil paint set, he remarked in his diary that ‘painting of Orgone phenomena will, if I acquire the technical skill, save me a lot of writing’.31 For Reich the act of painting and the finished product was the most efficient method to express orgonomic concepts. The description of Reich’s painting process echoes the emphasis on the centre in his therapy: ‘I continue painting. There is usually only a core of an idea. Around this core the colours and forms group themselves quite on their own. This is true self-regulation.’32 Reich’s paintings also intuitively develop around a core, not only in terms of a preliminary idea, but also in terms of composition. One of the most compelling examples is Swirl 1951 (fig.8), in which a spectrum of colours rotates around the focal point in the lower centre of the composition. The painting’s centrifugal flow parallels the movement of orgone as described in Reich’s texts.

In contrast to the arcing shapes depicted in Swirl, works like Gift beat out a rhythm that works on a haptic level, paralleling the flow of blood or energy through the body. In this way Noland’s paintings might be understood as vehicles for accessing one’s centre and for making a connection to other objects in the world. Far from cold and impersonal they should be understood as profoundly human ciphers for the efforts of the post-war subject to use therapeutic techniques to come to terms with its most troubling personal and social anxieties. Noland’s paintings both mirror the therapeutic process and generate it, allowing orgone energy to enter the pictorial field and activate it. As such Noland is – no less than Pollock – a kind of action painter. His abstraction touches the viewer not through the immediacy of indexing the painterly gesture on the canvas, but through the juxtaposition of colour and the precise execution of form that translate into pulsating energy. As the painting pulses so too could its viewer.