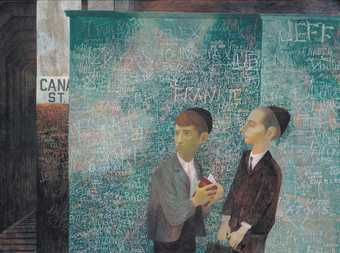

Orthodox Boys 1948 (Tate N05956; fig.1) depicts two religious boys dressed in typical yeshiva attire on the platform of Canal Street station, a subway stop in Lower Manhattan. Painted soon after the end of the Second World War, Orthodox Boys opens up a conversation about how spaces are marked and defined, both by individuals and communities, in a time and place of tremendous social change. By 1948, three years after the war, a space in Manhattan that was largely populated by Jews had metamorphosed into something more diverse. In this essay, close examination of Orthodox Boys will offer an opportunity to explore how the painting is intertwined with the Second World War, its aftermath and the changing face of Jewish life in its most prominent American centre.

Fig.1

Bernard Perlin

Orthodox Boys 1948

Tate N05956

The Lower East Side, where the majority of Eastern European Jewish immigrants settled when they arrived en masse in New York in the late nineteenth century, occupies a prominent place in the American imagination and in Jewish American history.1 Although New York was a city of immigrants, communities were often segregated into ethnic neighbourhoods. On the Lower East Side, Jewish newcomers consciously attempted to replicate the Old Country on American soil, thereby creating a haven for newly minted American Jews. To create and seek out such familiarity was typical of Jewish immigrants. In 1906 the writer Edward Steiner succinctly described the Jewish immigrant world, of which he was a part, and its re-creation in New York: ‘To them, [Rivington Street] is only a suburb of Minsk.’2 Even Abraham Cahan’s fictional character David Levinsky, the protagonist in the classic story of the Jewish immigrant experience, The Rise of David Levinsky (1917), sought such familiarity. When Levinsky arrived in America he travelled through New York City until he saw ‘a lot of Jewish people … [where] the streets swarmed with Yiddish-speaking immigrants. The sign-boards were in English and Yiddish, some of them Russian.’3 For Levinsky, Yiddish-speaking immigrants and Yiddish signboards were the symbols that served as his signifiers of Jewishness – the sights and sounds of his heritage.

Perlin grew up in Richmond, Virginia, far from a crowded Jewish urban space, but his youth was still permeated by Yiddishkeit – the richly vibrant shared traditions of Eastern European Jews. Yiddishkeit allowed a secular manifestation of Judaism in America, which included newspapers, poetry, theatre and even a socialist political bent – all in the Yiddish language. Perlin was the son of Russian, Yiddish-speaking immigrants. His observant family regularly attended religious services at a local synagogue and he received Hebrew instruction with a rabbi in preparation for his bar mitzvah. He practiced Judaism little after his move to New York City but the aspect of his religio-cultural heritage that most interested him, Yiddish, remained an enduring concern. Although he never followed through, Perlin wanted to enrol in a language school to properly learn Yiddish. Yiddish words, as well as Krazy Kat Yiddish accents and colloquialisms, peppered his everyday conversation throughout his life, and he strongly admired the Yiddish writer Sholem Aleichem.4 Even though he lived as something of a left-thinking atheist, to the end he retained some core Jewish traditions: he lit a yahrzeit candle (memorial candle) on the anniversary of his mother’s death as well as other loved ones, and privately celebrated Jewish holidays, usually through meals, thereby also indulging his love of cooking. At holidays Perlin cooked traditional Jewish foods like matzo ball soup, gefilte fish and kugel.5 A 1963 exhibition of Perlin’s art featured several paintings he made of food.6 That show included a painting titled Succoth c.1960, unillustrated and now lost; the fall harvest festival of Succoth, one of Judaism’s most food-centred holidays, is characterised by eating meals for a week in a special hut constructed outdoors. His library boasted a number of books on Jewish art and culture, including Leo Rosten’s classic The Joys of Yiddish (1968).7 Perlin’s life path seems to typify the Yiddish concept of the ‘pintele Yid’, or Jewish spark; however far one strays, one remains a Jew at heart.

Perlin’s sense of his Jewishness did not always come from a positive place. He was subjected to one particularly distressing episode of anti-Semitism in New York in around 1936. On a train sketching fellow passengers, as he often did on the subway, Perlin was chastised by a woman who cast especially vitriolic anti-Semitic aspersions at him – an incident he recorded at length in his diary.8 We also know about Perlin’s experiences with discrimination abroad. One of the most egregious instances he personally encountered was in the late 1930s in Poland, where he travelled to study after winning a prestigious Kosciusko Foundation Award. He remembered passing department stores forbidding Jews entry and in which Nazi attire was sold.9 During the trip he registered in a hotel under an assumed name and noted that he did so beneath ‘a big intimidating portrait of Adolph [sic] Hitler’.10 That same night, he recalled, he and his companion watched ‘a mini pogrom in the street below – two safe Jews looking at an outrage: some hundred or more yelling, murderous Nazis, waving clubs, as young as the two kids they were running after’.11 While visiting Danzig, Perlin jotted notes in his journal about the pervasiveness of Nazism and the behaviour of those around him: ‘We send postcards of Hitler … The department store that sells the Nazi uniforms. The parades of the Hitler Jugend. The exhibitions of Kosher Killings – the well-fed arrogance … Always Hitler & swastikas & Goering. “Mein Kampf.” A Free city? … We leave – it is good to go – a beautiful city – steadily becoming ugly … This is heartbreak! It is good to be out of “Germany”.’12 Later, when working as an artist-correspondent in occupied Greece, he witnessed Nazi atrocities – notably the destruction of a village when its residents were rounded up and burned alive. While abroad, as an artist-correspondent and otherwise, the fair-skinned Perlin hid his Jewishness and told people he was Catholic. These were necessary survival tactics, yet he still felt ashamed of them.13

Fig.2

Bernard Perlin

Dead Polish Boys c.1940

Pencil on paper

Collection of Michael Schreiber

© Bernard Perlin

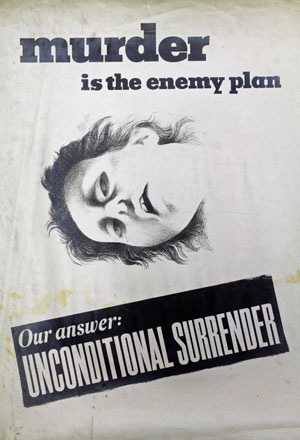

Fig.3

Bernard Perlin

Murder is the Enemy Plan 1943

Office of War Information poster

Collection of Michael Schreiber

© Bernard Perlin

Soon after returning from Poland in 1939, the artist seems to have worked through some of his trauma by making sketches of dead bodies based on a photograph he saw of piled corpses – and this is long before footage and stills of the death camps’ mass graves became available in 1945 (fig.2). Very carefully delineated and expressively shadowed, in this example there are two boys or young men (as there are in Orthodox Boys) that lie awkwardly, the angular forms of their limbs twisted for effect. The boy on the left covers his eyes, as if his last act was to shield himself from terror, while the one on the right has his neck stretched and contorted backward unnaturally. These sketches may have informed Perlin’s unsettling Office of War Information poster from 1943 (fig.3). Starkly rendered in black and white, the poster portrays the head of a murdered woman between the words ‘Murder is the enemy plan’, with a rejoinder, partly in oversized capitals, ‘Our Answer: UNCONDITIONAL SURRENDER’.14

The lure of the Lower East Side

With this background in mind, let us look more closely at Perlin’s life around the period he painted Orthodox Boys. In 1946, Perlin took an apartment on the Lower East Side, at 98 Pitt Street. After years in and around New York – initially settling in Newark, New Jersey, at age sixteen when he left Richmond to pursue his artistic education, and then in various locales in Manhattan – he had finally migrated to ‘Jewish’ New York. But that Jewish New York was something of a bygone era. Certainly there was a large concentration of Jews in the area and supporting communal structures, often with the Yiddish signboards celebrated by Levinsky, but a significant portion of the Jewish community had moved to more ‘upscale’ areas of Manhattan – that is, uptown to the north and to the suburbs. Nevertheless, the Lower East Side had achieved mythic status as a capital of Jewish culture, which attracted Perlin at the time, and persists to this day. As historian Hasia Diner eloquently put it in her study Lower East Side Memories: A Jewish Place in America: ‘The Lower East Side has become the American Jewish Plymouth Rock. It has come to stand for Jewish authenticity in America, for a moment in time when undiluted eastern European Culture throbbed in America.’15 Recently home from war-torn Europe, where he directly saw the devastation wrought by fascism and got a taste of the discrimination and persecution faced by his coreligionists, Perlin appears to have sought what he believed was a safe, immediate connection afforded by the Lower East Side. In other words, even as the more affordable housing may have played a factor in Perlin’s decision to move downtown, he hoped a retreat to a Jewish pocket of Manhattan – and its attendant Yiddishkeit – would provide a welcome sense of comfort.

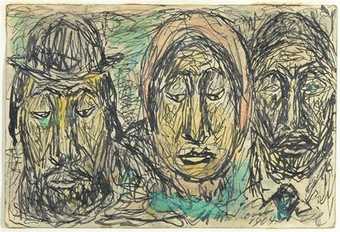

Fig.4

Abraham Walkowitz

Three Ghetto Faces 1904, published in Walkowitz’s 1946 book Faces from the Ghetto

© Abraham Walkowitz

Early artistic manifestations abound of this distinctive Jewish environment recreated on American soil. A number of Jewish American artists, including Abraham Walkowitz, Jacob Epstein and Raphael Soyer, began their careers by making imagery of the Lower East Side and its familiar Jewish world. Born in Siberia, Walkowitz moved to the Lower East Side as a child. His drawings and paintings of figures in traditional dress were among the first to portray Jews in their new surroundings. Three Ghetto Faces 1904 (fig.4), rendered in ink and watercolour, represents in extreme close-up three residents of the overcrowded Lower East Side, the most populated so-called ghetto for Jews in America. Two men with full beards and covered heads are pressed against the picture plane and in cramped quarters along with a single woman; no background is needed or could possibly be included. Walkowitz repeatedly depicted the Lower East Side as congested by its denizens in dozens of drawings. He rarely offered the streets and spectacles of the city; rather, he focused on the human element in the form of group and individual portraits, several of which were later collected in a book, Faces from the Ghetto, published two years before Perlin painted Orthodox Boys.16

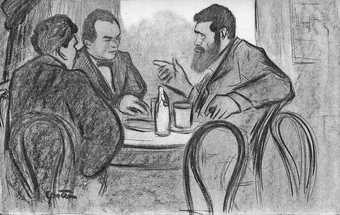

Fig.5

Jacob Epstein

Yiddish Playwrights Discussing the Drama 1902, from Hutchins Hapgood, The Spirit of the Ghetto (1902)

© Jacob Epstein

Also a resident of the Lower East Side, American-born Jacob Epstein frequently drew his surroundings. Epstein made fifty-two drawings and a cover design for gentile journalist Hutchins Hapgood’s The Spirit of the Ghetto (1902), a foundational book describing immigrant life and the Jewish world transplanted in America.17 Illustrating Hapgood’s prose, Epstein conveyed his brethren in everyday scenes, featuring his coreligionists’ distinctive attire and traditions. Epstein’s drawings include a rabbi certifying kosher food, pushcart peddlers and Orthodox Jews praying and studying, as well as aspects of Yiddish culture, including the ubiquitous Jewish café. In Yiddish Playwrights Discussing the Drama, for instance, three men in modern, westernised attire partake in serious conversation in one such café (fig.5). Like Walkowitz, Epstein did not look outward past the narrative of individual lives of the Lower East Side’s inhabitants to the urban cityscape, and at no time does he portray any evidence of strife or unease for Jews in their new homeland. Ultimately, sculpture became Epstein’s favoured medium, which he pursued especially after he moved to England permanently in 1905. Critics tarred his modernist sculpture with anti-Semitic epithets even when the subjects were not ‘Jewish’ – a direct contrast to the positive post-war reception of Perlin’s Orthodox Boys, a work of art much more explicitly Jewish in context than anything Epstein ever made.18

Fig.6

Raphael Soyer

East Side Street c.1928

Courtesy of Forum Gallery, New York

© Estate of Raphael Soyer

Raphael Soyer, who immigrated to America in 1912, painted a small canvas of Delancey Street, just a few blocks away from Perlin’s apartment and the subway locale featured in Orthodox Boys. Words clearly play a prominent part in Orthodox Boys, and those words are not as innocuous as a signboard or a street sign, such as those found in Soyer’s East Side Street c.1928 (fig.6). One of the most detailed images of the urban ghetto by a Jewish artist, East Side Street is painted from the third floor window of Soyer’s Lower East Side studio. A long, narrow street cuts through the middle of the painting, with a trolley in the distance, a horse-drawn carriage in the mid-ground and a small pushcart peddler wheeling his way toward the viewer. On the right side of the street, groups of Jewish men wear black hats and long black coats, the customary dress of Orthodox Jews. These small figures extend into the distance, even past the tiny lamppost at the back of the canvas. On the left side of the painting, a series of small buildings press up against each other. Some signs can be made out: a white hanging sign that reads ‘Lunch’ appears to the left of the horse-drawn carriage and the sign on the corner store has some recognisably Hebrew lettering. The words are an English transliteration that say ‘Corner Flower’, probably meaning ‘Florist’, and the owner’s name underneath, here also in Hebrew (‘Zvi Forenson’). Soyer’s Lower East Side is one of comfort and safety, whereas Perlin has infused his image of the Lower East Side, that of the late 1940s, with tension and disquiet in paintings such as Orthodox Boys.19 For as Perlin would have discovered, he had moved to Lower Manhattan after demographic shifts had destabilised the once-firm Jewish identity of the area – a reality that may very well have prompted him to depict some of those remaining Jewish figures in his immediate environment, and initiated the words on the Orthodox boy’s book. As he cleanly inscribed in the only readable portion of the Hebrew book held by the boy: ‘Why, my son, did you come late?’.

Vacant Lots and the refuse of war

Like Soyer, Perlin was inspired to paint a Lower East Side scene from his studio window: Vacant Lots (fig.7), made in the same year as Orthodox Boys. Vacant Lots, which helps shed some light on Orthodox Boys, pictures a single boy, around the same age and in the same neighbourhood as the boys in its ‘companion piece’. Also donning a kepah but wearing less traditional attire, the boy in Vacant Lots scales a chain-link fence. His fingers curl around the metal enclosure, his feet appearing to move in fast motion, perhaps an indication of his fear. The exaggerated blood red of the brick tenement buildings increases the anxious timbre of the painting, as do the boarded-up and darkened, empty windows. From what does the boy run such that he must climb a fence that will drop him into copious piles of paper and other rubbish? The symbolism here, intrinsic to work by many magic realist artists, can be usefully parsed in comparison to Orthodox Boys. In Orthodox Boys, where do those foreboding train tracks lead, and in Vacant Lots, what lies between the empty spaces of the claustrophobically close buildings?

Fig.7

Bernard Perlin

Vacant Lots 1948

Private collection

© Bernard Perlin

The boy’s palpable apprehension in Vacant Lots bears comparison with the Orthodox boys’ expressions. Certainly they are nervous, but in conjunction with Vacant Lots we may further notice that the suspicious boy on the left in Orthodox Boys cradles the book in both hands, perhaps attempting to shield the Hebrew lettering and at the same time keep the text concealed by moving the book protectively near to his body. The train tracks look more ominous, even infernal, when paired with the murky, cavernous lot. They recall that of the narrow alley that lies beyond a shadowy girl with a hula hoop in an canvas considered a chief precursor to magic realism: Giorgio de Chirico’s Mystery and Melancholy of a Street 1914 (private collection), a painting Perlin is likely to have seen many times in reproduction. Many magic realist paintings appear deliberately ambiguous and unsettling, offering enigmatic allegories in need of decoding.20

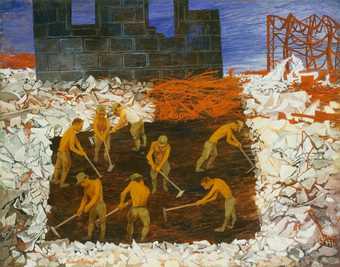

Fig.8

Bernard Perlin

Tokyo (Boys Gardening) 1945

Illustration for Life magazine, 19 November 1945

© Bernard Perlin

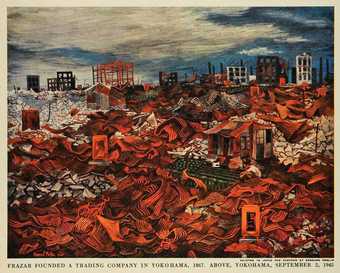

Fig.9

Bernard Perlin

Bombed Yokohama 1945

Illustration for Fortune magazine, 2 September 1945

© Bernard Perlin

The strewn paper in Vacant Lots evokes the destruction found in three further Perlin works that more directly explore the consequences of war. As an artist-correspondent for Life and Fortune magazines, Perlin saw the aftermath of bombings in Japan, which he recorded for publication. In Bombed Tokyo 1945 (collection of Michael Schreiber), Tokyo (Boys Gardening) 1945 (fig.8) and Bombed Yokohama 1945 (fig.9), the latter of which appeared as an illustration in Fortune magazine, Perlin represented the devastation of war as dense piles of detritus amid skeletons of buildings. Yet that stylised debris, amorphous in conception, bears similarities to the scattered paper in Vacant Lots. To that end, I would argue that Vacant Lots does not stop at raising the spectre of the destruction of the Second World War. Like Orthodox Boys, the work brings the impact of the Holocaust – the destruction of the Jews – onto American shores. Each of the paintings adopts widely understood signifiers of the Holocaust.21 Vacant Lots, painted first, employs a metal fence – often used to imprison Jews within ghettos as well as concentration camps. Orthodox Boys suggests a train, the preferred mode of transporting Jews and other ‘undesirables’ to death camps. The resonances in Vacant Lots become sharper and more explicit in its successor, with Perlin’s pairing of the train track with the most recognisable sign of Jewish oppression, the swastika, which appears on the wall in Orthodox Boys no fewer than six times. Three frightened boys populate these highly symbolic paintings, ostensibly about the American scene but surrounded by the menaces of the Nazi genocide.

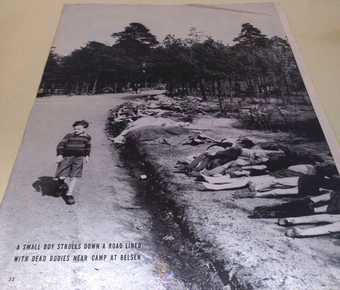

Fig.10

Page from Life magazine, 7 May 1945

Bernard Perlin Papers, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven

The refuse of war that Perlin strews across the aforementioned works conjures one other association, directly and most morbidly associated with Holocaust iconography: that of the piles of corpses found in mass graves uncovered upon liberation of the camps. Horrifying images of such scenes circulated widely in press photographs and newsreels to which Perlin paid close attention; he tore out a full-page photograph from the 7 May 1945 issue of Life magazine that showed dozens of corpses lining a road near the Bergen-Belsen death camp, retaining the clipping for the remainder of his life (fig.10).22 Perlin’s use of anthropomorphic detritus as a stand-in for human forms is hardly unique. Another artist associated with magic realism, Peter Blume – who was also Jewish – included gourds as a metaphor for the bodies that haunted him in a painting from two decades later: Recollection of the Flood 1967–9 (collection of Dorothy Kobak). Blume asserted that Recollection of the Flood pictured the aftermath of the 1966 flood of the River Arno in Florence when survivors took refuge in churches and public buildings, but close attention suggests that the canvas presents an elaborate allegory about the Holocaust.23 Likewise, the debris in Vacant Lots, overflowing and cast aside, may very well reflect the impact on Perlin of seeing imagery of the unspeakable conditions of the death camps.

Let us return to those provocative words recorded in the boy’s Hebrew book (‘Why, my son, did you come late?’), which imply another possible meaning: all three boys could stand as symbols of what might have been Perlin’s own dark fate. If one is late to arrive at a train station, then one misses the train – which in a Jew’s case in the 1940s might mean survival. Perlin himself narrowly missed that train; during his 1938 trip to Poland, a taxi driver warned Perlin to leave the country because, as the artist later paraphrased, ‘This is a very bad place for Jews … The shit is going to hit the fan, and here you are, and if you have any sense, get out of here.’24 The question of arriving too late is set in a positive context here, but the query might also be related to some survivor’s guilt on Perlin’s part: by a quirk of fate he was born looking like a Swede, an identity, in fact, that he acknowledged he took on while in Poland.25 Perlin’s Orthodox Boys, however, would not have had such a luxury by virtue of their distinctive attire and more Semitic features.

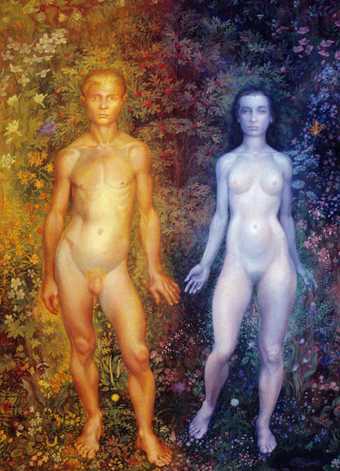

Fig.11

Bernard Perlin

The Garden 1948–9

Princeton University Art Museum, Princeton

© Bernard Perlin

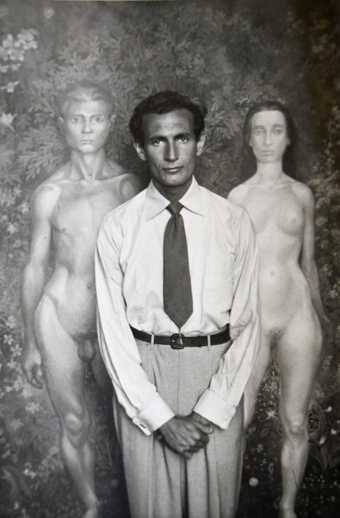

Fig.12

Jared French

Perlin in Rome 1949

© Jared French

As the pairing of Orthodox Boys and Vacant Lots intimates, Perlin’s war experiences had profoundly lasting effects, and what he hoped was a refuge back on American soil may have proved a disappointment. That, and his own ambitions, compelled Perlin to apply for a Chaloner Prize Foundation award, which in 1948 took him to Italy for a year, a stay furthered by a Fulbright scholarship that mean he could remain there until 1954. Thus, in 1948, soon after completing Orthodox Boys and Vacant Lots, he moved back to what was finally a free Europe, where Perlin himself found freedom with a new artistic style. The Garden 1948–9 (fig.11), painted soon after his arrival in Italy and much larger than its predecessors, also includes two figures, here a young man and woman far from an urban setting. Portrayed in a much less crisp fashion than his social realist conceptions, these Adam and Eve figures stand amid luxurious, colourful foliage, fully nude and apparently relaxed, and in a photograph taken by Jared French in Rome in 1949, the two painted bodies are bisected by the figure of Perlin himself (fig.12). Art historian and curator Robert Cozzolino proposes that The Garden ‘was conceived as an image of peace and hope – the setting for a new start to a world that had recently endured a second catastrophic global war’.26 Indeed, those connotations do pervade The Garden, picturing an imaginary setting far from a world where eleven million people, of which six million were Jews, could be systematically slaughtered. The Garden, too, depicts an imagined locale far from an imagined Jewish Lower East Side. Perlin also had his new start in Italy, as an artist and as a Jew.