Published in 2002, sociologist and philosopher John Holloway’s Change the World without Taking Power inspired a variety of attempts to analyse and reckon with the wave of anti-capitalist, alter-globalisation protests of the early 2000s. Broadly speaking, the alter-globalisation or global justice movement sought to develop a cooperative, international politics of solidarity in opposition to the dominant mode of capitalist global integration.1 Allan Sekula’s Waiting for Tear Gas 1999–2000 (Tate L03355) captures a crucial moment in the breaking of the neoliberal consensus described by Holloway, who saw the global justice movement as underpinned by a dwindling of intellectual and political investment in the idea of capturing the state through a mass movement or party. In a few paragraphs published alongside Waiting for Tear Gas, Sekula acknowledged this, describing alliances on the streets of Seattle that were ‘stranger, more varied and inspired than could be conveyed by the cute alliterative play with “teamsters” and “turtles”’.2 The novelty of this ‘new face of protest’, as he called it, was widely understood through the apparently terminal crisis of the mass party at the turn of the millennium. To register this shift, Sekula’s textual and photographic record of the ‘Battle for Seattle’ produced what he referred to as a ‘simple descriptive physiognomy’.3 For Sekula, the body, as opposed to the image, became the site from which a struggle against the existing order could be produced. In Waiting for Tear Gas, the bodies of protestors dressed as turtles and devils, men wearing gas masks, bare-breasted women and Latino workers form blockades, clap and chant, rest and hang about, ‘waiting for tear gas’ and other forms of state violence. Through Sekula’s emphasis on embodiment in his slide sequence, he registered scepticism towards the notion that the global justice movement relied upon a networked ‘cyberspace’ for the emergence of a newly formed collective subject: the ‘multitude’.4

Waiting for Tear Gas mobilises the body as evidence against the neoliberal fantasy of accumulation without violence and dispossession, capturing the fungibility of human labour power in the workplace as well as in conflict with the police. This essay explores Sekula’s emphasis on embodiment as the quality that makes Waiting for Tear Gas capable of describing the otherwise amorphous relation between ‘teamsters and turtles’. Moreover, this study will stress embodiment as the thread connecting Waiting for Tear Gas to non-linear and diverse histories of art and protest. By attending to a longer durée of uprisings and attempts to rethink the social within art as well as politics, here we will see how the events captured by Sekula were born out of earlier struggles, positing a series of connections along the lines of what the social historian E.P. Thompson called ‘constructive speculation’. As Thompson describes it, this is defined as making associations in order to animate and produce counter-narratives that may have otherwise remained buried. Aptly for writing about Sekula, an artist who has been preoccupied with the sea in much of his other work, Thompson describes constructive speculation as an attempt to reconstruct a tract of secret history that is ‘buried like the Great Plain of Gwaelod beneath the sea’.5

Fig.1

Allan Sekula

Waiting for Tear Gas 1999–2000

Tate L03355

© Estate of Allan Sekula

Fig.2

Allan Sekula

Waiting for Tear Gas 1999–2000

Tate

© Estate of Allan Sekula

In addressing how these embodied relations are manifested within Waiting for Tear Gas, we can observe a literal ‘red thread’ that builds up connections between bodies through clothing, physical attributes and degrees of colour saturation in the photograph. This thread traverses the imagery from traffic lights to a protestor dressed as a devil, through jackets, flags, banners, bandanas and crimson hair. Scarlet streaks of colour with specific material properties (cotton, hair, plastic) eventually shift towards saturating the whole image with an abstract wash when night falls and the lack of a flash sees the scene lurching from yellow to red. The most extreme reddish-yellow saturation indicates terror, as in the photograph of two police riding the back of a heavy vehicle, totally anonymised through their armour (fig.1). Yet in the previous photograph, reddish saturation indicates pleasure, as two women play at cop and arrestee in the doorway of a sex shop (fig.2). One woman, in a short red dress, faces the wall. She arches her back, spreads her legs and raises her hands above her head, while another woman, turning to face the camera, laughs and gestures as if to spank her. The pleasure – importantly here between two women – confronts the violence of the previous image, forming a weapon made up of humour and sex.6 The reddish saturation of these photographs insists that they are part of the same continuum, with the precarious unity between the women partly produced through the threat of the policeman’s baton, indicating both the specific proximity of the protests and the criminalisation of sex work.

As the art historian Benjamin Young has proposed, this photograph of two sex workers may represent a ‘ludic break from work’.7 Following this suggestion, we could speculate that the photograph captures time away from servicing versions of the dull beige trench coats Sekula photographed entering the hotel lobby (fig.3). Young also asks whether or not the women are providing a ‘preview meant to advertise the commodity sold inside’.8 However, situated in relation to other photographs of women within the series, this image lacks the necessary sexual charge to act as a preview. The direction of the women’s action towards the camera suggests a correspondence instead with the de-sexualised bare breasts we see in other photographs (fig.4). Women’s bodies in Waiting for Tear Gas seem to sneer towards a male gaze, rather than seeking to seduce.

Fig.3

Allan Sekula

Waiting for Tear Gas 1999–2000

Tate

© Estate of Allan Sekula

Fig.4

Allan Sekula

Waiting for Tear Gas 1999–2000

Tate

© Estate of Allan Sekula

Film theorist and art historian Kaja Silverman defines the ‘red thread’ described here as representative of a shift within Sekula’s use of colour since the early 1990s. As she argues, the increased importance of colour signals Sekula’s growing investment in the ‘affect’ of an image. By this Silverman means a feeling marked by speculation, and a step towards the kinds of social, bodily ‘reverberations’ we associate with the thought of Walter Benjamin, with his stand against an orthodox, scientific materialism and for ‘mysterious’ affinities. Such mysterious affinities lend themselves to Thompson’s ‘constructive speculation’ and to the making of histories that work against dominant narratives by refusing the accepted logic of how those narratives are produced.9 Instead, the reverberations of the red thread in Waiting for Tear Gas give shape to powerful, embodied relations that describe the possibility of shattering the primary fantasy of capital: that of a world without obstacle to profit.10

Waiting for Tear Gas magnifies the forms of repression that produce the necessity to struggle collectively for new forms of life, a quality that can be related to contemporaneous developments of the period in what has variously been called socially engaged art, relational aesthetics or social practice. As art historian Steve Edwards describes, both ‘relational aesthetics’ and the ‘new realism’ (with the latter category being applied to Waiting for Tear Gas) respond to the upswing of protest that marked the millennial conjuncture.11 For Edwards, these art forms are notable in that they are collective and frequently ‘appear under the sign of anti-capitalism’. Neoliberalism, by contrast, remains solely capable of valorising the individual or, at best, a religious or military collective subject.12 In the view of prominent commentators on social practice such as Claire Bishop, collective forms of art within neoliberalism have nevertheless tended to cohere with the hegemonic socio-economic agenda.13 Furthermore, Bishop views collaborative practice as emerging through political failure, writing that ‘It is tempting to date the rise in visibility of these practices to the early 1990s, when the fall of Communism deprived the Left of the last vestiges of the revolution that had once linked political and aesthetic radicalism’.14 This stands in contrast to Edwards’s affirmative point that social practice emerges alongside the movement for global justice. I want to use these divergent periodisations and assessments of a newly politicised, collective art practice at the turn of the millennium to negotiate the common view that the tactics and alliances Sekula captured in Waiting for Tear Gas marked a historical break not only in terms of left organisation, but also with regard to the history and subsequent relation of art to political protest.

Fig.5

Allan Sekula

Waiting for Tear Gas 1999–2000

Tate

© Estate of Allan Sekula

As with the image of the police saturated in red discussed above, Waiting for Tear Gas evidences the ‘militarisation’ of the police. Such images should always direct us to ask where the trial runs for this militarisation took place, and, as described by journalists Alexander Cockburn and Jeffrey St Clair in their account of the ‘battle’, there was a strong sense in Seattle that the behaviour of the police came as no surprise to black and Latin American demonstrators.15 The unmovable reality of the police’s role in the United States cannot be disconnected from their existence as a racialising force. The writers Steve Martinot and Jared Sexton stress the process of racialisation as a system of meanings assigned to the body, with ‘police spectacle’ – by which they mean brutality and harassment – as a ‘banal’, everyday form of this violence serving to constitute the ‘distinction between those whose human being is put permanently in question and those for whom it goes without saying’.16 As Martinot and Sexton explain, ‘The truth is that the truth is on the surface, flat and repetitive, just as the law is made by the uniform.’17 The expected onslaught of state violence is what the ‘waiting’ is about in Sekula’s series, with its flat, repetitive quality magnified in photographs such as the one of demonstrators holding up a mirror towards a line of riot cops (fig.5). Sekula’s camera – like the mirror, a technology of light – repeats and forces this police spectacle to the surface, providing a portal through which we can tunnel into other histories that complicate conventional histories of social practice, ‘new realism’ and Waiting for Tear Gas.18

Fig.6

Demonstrations in Maidan, Ukraine, December 2013

Photo © Sergei Chuzavkov / Associated Press

Fig.7

Demonstrations in Ferguson, Missouri, 10 October 2014

Photo © Associated Press

The tactic of directing a mirror towards the police at demonstrations has become more commonplace in recent years. This has been captured in photographs of the demonstrations at Maidan in the Ukraine in December 2013 (fig.6). Similarly, after the police killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, on 9 August 2014, mirrors were raised towards the police at multiple demonstrations across the United States. In Ferguson, a group of artists including Mallory Nezam, De Andrea Nichols, Marcis Curtis, Damon Davis, Derek Laney, Sophie Lipman and Elizabeth Vega produced a mirrored coffin, which they carried through a protest on 10 October 2014 and delivered to the police station (fig.7). As with Silverman’s analysis of Sekula’s employment of colour after the 1990s, these actions produced a certain affect, whether this occurred in the live, momentary reflection of the policeman’s face in the mirror, or in the photographing of this encounter. The mirror simultaneously heightend and examined the confrontation between police and protestors, seeking to mediate and document the pre-determined form of this encounter as one marked by the violence of police spectacle. Alongside this recent use of mirrors during protests, it is notable that they were also employed at Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp in the 1980s as a means of reflecting police brutality. By triangulating Seattle, Greenham Common and Ferguson, we can counter the limited, ahistorical view that Sekula’s photographs of Seattle captured a fundamental break with earlier forms of leftist political organisation and protest.

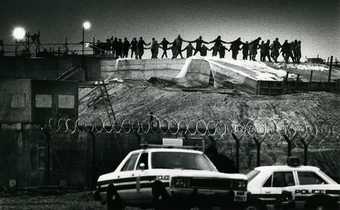

Fig.8

Greenham Common woman with mirror, c.1982–4

Courtesy of Hazel Pegg

On 11 December 1983, an action entitled ‘Reflect the Base’ was held at Greenham Common Peace Camp, located in the British county of Berkshire, which involved 5000 women holding mirrors aloft and surrounding a nuclear base (fig.8). As Alice Cook described in her account of the movement, co-written with Gwyn Kirk in 1983, Greenham Common was ‘a round-the-clock protest against cruise missiles, [and] a resource – a women’s space in which to try to live out ideals of feminism and nonviolence’.19 Begun in 1981 by a group of Welsh women, the camp lasted for nineteen years as a struggle against the presence of nuclear weapons at RAF Greenham Common. From the start, the activity of the camp moved beyond typical street demonstrations into a long-standing occupation that, as Cook describes, sought to model a future world without patriarchy and violence. A year before ‘Reflect the Base’, 3500 women had encircled the nine-mile nuclear base in an action called ‘Embrace the Base’, which protested against the hosting of American cruise missiles at Greenham (fig.9). Other activity included blockading construction work and decorating the perimeter fence with photographs, yarn and soft toys as well as pulling vast sections of the fence down and dancing on top of missile silos.

Greenham activist Rebecca Johnson describes ‘Reflect the Base’ as more militant than earlier actions because it followed two years of activity in which thousands of Greenham women had been arrested and imprisoned. There were also two major offenses against the camp around the time of ‘Reflect the Base’ that exceeded the usual terror perpetuated by soldiers, police and the press. In November 1983 Defence Secretary Michael Heseltine declared that those protestors who trespassed the guarded areas of the Greenham base risked being shot. This statement was contemporaneous with the arrival of the first US cruise missiles to be stationed at the base.20 As suggested, the use of mirrors in such situations plays on affect and, as Johnson describes, one of the intentions of ‘Reflect the Base’ was to force ‘thousands of armed soldiers and police’ to ‘see their own faces, guarding these nuclear weapons of mass suffering’.21

Fig.9

Embrace the Base

Greenham Common, 1982

Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament Archives

Photo © Ed Barber

Like the demonstrators in Ferguson and those who hold the mirror up to the police in Waiting for Tear Gas, Greenham women were involved in a struggle which linked political and aesthetic radicalism in ways that far exceed Bishop’s assessment of social practice as emerging through defeat. These mirrors can deflect the geographical and temporal limits of her claim that the end of the Soviet Union in 1989 marked a severance point for practices that made such a link. Rather than taking place at work, through a party or a union, Greenham, Seattle and Ferguson all involve straightforwardly protesting against deaths produced by the state, at home and abroad. As the example of Greenham suggests, such movements that shifted away from the dominance of the party and state within the left precede 1989, or that millennial moment. Women had been attempting to break the party long before, and like the alter-globalisation movement, sought to mobilise the kinds of affinities Silverman associates with Sekula’s use of colour in Waiting for Tear Gas.

In her account of Greenham, Caroline Blackwood noted that on her first visit to the camp she met an older woman called Pat who told her ‘The young girls on the camp really love their symbols … You know they weave all these webs. They hold mirrors up to the base so as to make it reflect its own evil.’22 It is easy to bristle at the sentimental quality of these actions, as many feminists during that moment did. As Judy Cox writes, some on the left viewed actions such as ‘Reflect the Base’ as trivial, and the association of militarism and US imperialism with patriarchy as an unnecessary ‘vilification of ordinary men’.23 Within these arguments, Greenham was viewed as producing conspiratorial connections between patriarchy and militarism, too esoteric in the invocation of webs and mirrors, and too much about a lifestyle. Similar criticisms would eventually be levelled at the movement for global justice, and after the recent uprisings in Ferguson, Oakland and elsewhere against racist police brutality, the spectre of revolutionary spontaneity rather than party-led organisation has inevitably provoked anxiety in certain sectors of the left.24 Yet the red thread between the photographs in Waiting for Tear Gas can be unspooled further, connecting the mirrors at Greenham, Seattle and Ferguson. Rather than view Greenham as a failure or a Cold War relic, or Seattle as an entirely new struggle, we should understand the concerns of all as located upon the continued promise of the commons and as against state violence. Crucially, we can speculate that Greenham could and did close in 2000 because Seattle was happening, and as Sekula noted, there was a ‘strong feminist dimension’ to the Seattle protests.25

Fig.10

Unidentified photographer

Greenham Common protesters

Fig.11

Raissa Page

Panorama of women protesters at the Greenham Common airbase, 1983

© Raissa Page

This dimension did not preclude an emphasis on labour, as the sex work photograph makes clear. The struggle around work foregrounded blockages, as Sekula describes:

It was the men and women who work on the docks, after all, who shut down the flow of metal boxes from Asia, relying on individual knowledge that there is always another body on the other side of the sea doing the same work, that all this global trade is more than a matter of a mouse-click.26

This targeting of logistics recalls the port blockage in Oakland of August 2015 against police brutality in the aftermath of Ferguson.27 Greenham women may have occasionally operated on more arcane principles than these port blockages, but their use of mirrors and their bodies formed real obstacles, whether dancing atop a silo or lying down in front of police cars (figs.10 and 11). Writing speculatively, we can suggest that the mirrors link these blockages and produce a new temporality. As Walter Benjamin wrote, ‘Let two mirrors reflect each other; then Satan plays his favourite trick and opens here in his way (as his partner does in lovers’ gazes) the perspective on infinity.’28 The perspective on infinity produced by the mirror parallels the expanse and difficulty of the struggles discussed here. As a woman called Carol wrote of her feelings towards nuclear catastrophe in the feminist magazine Spare Rib in 1980, ‘There isn’t the language to deal with this. It’s like trying to imagine infinity. It’s so vast that I am totally pessimistic.’29 Yet as my triangulation here between the protest-mirrors at Seattle, Greenham and Ferguson hopes to convey, occasionally the feeling of infinity gains an affect other than pessimism. These mirrors work against the two-way mirrors of police stations and prisons and instead bounce back the gaze of the police and deflect evil, becoming modern day versions of Perseus’s shield against Medusa.