Photo-essays ‘bringing home the war’ were a staple of American visual culture in the 1960s. Issue after issue of Life magazine visually narrated the actions of American men doing battle in foreign lands, doing battle to foreign bodies. The Vietnam War (1955–75), in short, loomed large in the cultural imaginary of Cold War America – or so it would seem. Discussing the development of his practice in the opening pages of his 1984 anthology Photography Against the Grain: Essays and Photo Works, 1973–1983, Allan Sekula explained:

Thirteen years ago, when I first began making photographs with any seriousness, the medium’s paramount attraction was, for me, its unavoidable social referentiality, its way of describing – albeit in enigmatic, misleading, reductive and often superficial terms – a world of social institutions, gestures, manners, relationships … At the time photography seemed to me to afford an alternative to the overly specialized, esoteric, and self-referential discourse of late modernism, which had, to offer only one crude example, nothing much to say about the Vietnam War.1

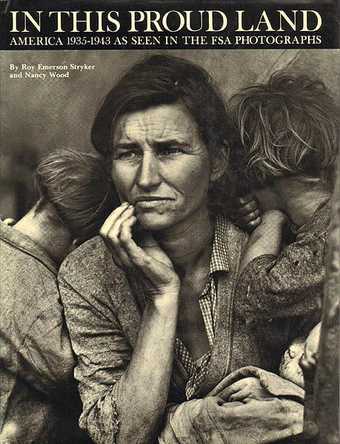

Fig.1

Cover of In This Proud Land: America 1935–1943 as Seen in the FSA Photographs by Roy Emerson Stryker and Nancy Wood, Greenwich, Connecticut 1973

Sekula seems to be suggesting that Vietnam was everywhere but the art world. Although hardly true, Sekula’s recounting, his ‘fish story’, like all the tales and histories we sell and are sold, is nonetheless telling.2 His decision to redeploy those subjects and conventions that he insisted had been disqualified by the art world – physical work and the war ‘at home’ – goes a long way towards explaining why it is that his photographic practice roused little interest among curators and critics until the early 2000s. As Benjamin Buchloh argued in 1995, Sekula’s work was not simply ignored (there has not been a single retrospective of his work in the United States to date); it was wholly ‘illegible’.3 Access to the codes and conventions necessary for making sense of Sekula’s histories and ‘fish stories’ had been too deeply repressed by the Cold War refashioning of documentary as a record of America’s tenacity and triumph.4 By the 1970s, when Sekula picked up a camera, documentary was synonymous with the panoply of worn and weathered faces catalogued in Roy Stryker and Nancy Wood’s In this Proud Land (1973) (fig.1). Said differently, in the 1970s, as in the 1940s, the wars at home – the wars on class and race – were once again forgotten.

The question posed in this essay follows suit. Despite the recent recognition of the critical value of Sekula’s practice, and despite the art world’s embrace of documentary as a critical practice in the early 2000s, are we still blind to many of the codes and conventions framing Sekula’s work?5 Is there, in other words, another blind spot lurking in our study of Sekula that comes into view when we venture a closer look at Waiting for Tear Gas 1999–2000 (Tate L03355)? More than any of Sekula’s other essays and slide sequences, Waiting for Tear Gas is often argued to be emblematic of ‘good’ political photography. In fact, as noted in the introduction to this In Focus project, it set a precedent for critical protest art. Efforts to make this argument often draw on comparisons with the work of a range of Sekula’s contemporaries, from Joel Sternfeld’s portraits of men and women protesting the G8 summit in the Italian city of Genoa in 2001 to Andreas Gursky’s large-format, highly detailed landscape shots of the overloaded spaces of global capital.6 If Sternfeld, like Sekula, shot his subjects from the street and evaded iconic images of ‘the face of protest’, Gursky, whose photographs typically provide a view from above and at a distance, reproduced the smooth spaces of globalisation, those Gehry-like spaces, which eradicated the possibility of representing, literally and visually, subjects as social (figs.2–4).

Fig.2

Joel Sternfeld

Man, Sweden

Printed in Treading on Kings (2001) with accompanying caption: ‘This picture was taken the next morning, after the attack on the Armando Diaz School. Depicted is a mark made by a police taser. Protester declined to revise his statement made the previous evening.’

© Joel Sternfeld and Luhring Augustine

Fig.3

Allan Sekula

Waiting for Tear Gas 1999–2000

Tate L03355

© Estate of Allan Sekula

There is nothing wrong with these comparisons; they are productive. They do, however, privilege the present over the past. Focusing on the ‘now’ and the ‘new’, they sidestep Sekula’s sustained engagement with a long history of photography. ‘Good’ political photography, after all, is not photography on the ‘right’ side of mainstream media, nor is it photography on the ‘right’ side of the art world. It is photographic work deeply engaged with the politics producing these categories and their role in the organisation of our histories of photography. Waiting for Tear Gas, in turn, contends with much more than the significance of Seattle or the evident violence of globalisation. It contends as well with the controversial logic of street photography – of getting close up, stepping into the crowd and watching others act and work. It contends with what Sekula called the ‘traffic in photographs’, the ‘social production, circulation, and reception of photographs in a society based on commodity production and exchange’.7 The Seattle in Waiting for Tear Gas is both open – to new histories and political associations – and codified – already told and sold.

Fig.4

Andreas Gurksy

99 Cent 1999

Museum of Modern Art, New York

© 2001 Andreas Gursky

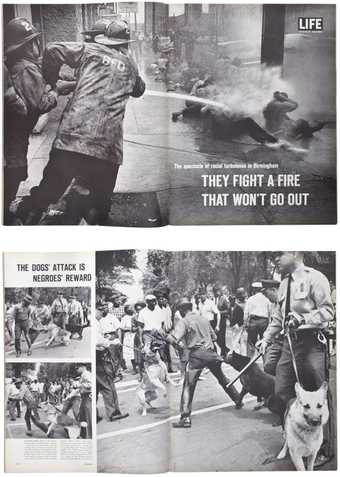

Assessing this aspect of Sekula’s slide sequence calls for a return to the heyday of street photography, to the 1960s and specifically to one of the most controversial representations of bodies taking to the streets in protest: the nine-page, twelve-photograph essay in Life covering the May 1963 civil rights demonstrations in Birmingham, Alabama (fig.5). Shot and assembled by Charles Moore and published in the 17 May 1963 edition of Life, this essay recorded the excessive and extreme brutality wielded by the white police state against its black public. ‘The Spectacle of Racial Turbulence in Birmingham: They Fight a Fire that Won’t Go Out’ opens with a single photograph of Birmingham firemen unleashing their fire hoses on nonviolent protestors. Enlarged to stretch across the fold of the page and appointed to mirror its sweep, this photograph of black bodies ‘flung’ into the air ‘like sodden dolls’, as one newspaper reported, was followed by two pages with three rotating views of a police dog attacking Walter Gadsden, a young black bystander.8 Certainly spectacular, as the editorial’s title announced, Moore’s coverage of the protest was hardly unprecedented. Making a spectacle of racial violence was commonplace by the 1960s, and had been commonplace since photography’s invention in the 1830s.9 However, blown up and narrated over several pages of one of the most widely circulated media outlets in the US, Moore’s photographs had an unprecedented effect on Martin Luther King Jr’s campaign to shake white moderates from their complacency about the progress of race relations in America. In the wake of the publication of the Life spreads, many white readers openly condemned racial violence, while President John F. Kennedy and the US Congress finally pushed through long-stalled civil rights legislation.10

Fig.5

Spreads from ‘The Spectacle of Racial Turbulence in Birmingham: They Fight a Fire That Won’t Go Out’, LIFE magazine, 17 May 1963

Photographs by Charles Moore

To recall Moore’s photographs in the context of Waiting for Tear Gas might seem arbitrary. Yet as Andy Warhol’s 1964 series Race Riot (Tate P77809) suggests, these photographs did penetrate what Sekula had described as the ‘esoteric’ and ‘overly specialized’ discourse of late modernism (fig.6).11 More to the point, Warhol’s appropriation and repetition of Moore’s photograph of a police dog attacking Gadsden prompts us to reconsider an issue at the centre of Sekula’s slide sequence – namely, our wholly negative reaction to overly spectacular representations of street protest in the mainstream news. Warhol’s appropriation and repetition of the iconic shot reminds us, in short, that public protest is inseparable from, produces and is produced by, media spectacle.

Fig.6

Andy Warhol

Birmingham, Race Riot 1964

Tate P77809

© 2016 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Artists Right Society (ARS), New York and DACS, London

If it is true, as art historian Martin Berger argues in his extended study of Moore’s Life spread, that the way that the white press keenly followed and framed only violent actions in Birmingham ‘reduced’, in Berger’s words, ‘the complex social dynamics of the civil rights movement to easily digested narratives’ of white-on-black violence, this is also exactly why King staged the protest.12 King chose Birmingham for the May protest because he suspected and hoped that the most segregated city in the nation would erupt in violence, thereby attracting photographers.13 In King’s words, ‘Instead of submitting to surreptitious cruelty in thousands of dark jail cells and on countless shadowed street corners, he would force his oppressor to commit his brutality openly – in the light of day – with the rest of the world looking on’.14 In turn, despite the reduction of the events that May to a single narrative of white actors exercising power over black victims, spectacular representations of police violence were cultivated and deemed necessary.15 It was the press coverage, the fact that the world could be and was watching, and not the violence that propelled Kennedy’s actions. Kennedy did not react to the events taking place in the streets of Birmingham – to racism – but rather to the photographs. More exactly, he reacted to the realisation that the photographs, which also circulated in the international press, made America look less than democratic in midst of the Cold War conflict.16 ‘It went without saying’, as historian Adam Fairclough has noted, ‘that Birmingham gave the Soviet Union a propaganda bonanza’.17 Moore’s photographs simultaneously reproduced and undid the status quo, offering critiques of media in which the spectacularisation of violence is always ‘bad’ press.

Fig.7

Allan Sekula

Waiting for Tear Gas 1999–2000

Tate

© Estate of Allan Sekula

Moore’s photographs certainly do not record a motley crew of protesters, the defining characteristic of alter-globalisation (or alternative globalisation) demonstrations, as both Terri Weissman and Larne Abse Gogarty explore in this project’s final essays.18 Yet his images do demonstrate that on the street, in public, a protest is always a mediated event, one that is defined by and through its representation. They indicate the fallacy of a choice between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ politics. Thus, if Sekula never acknowledged this specific war at home, Waiting for Tear Gas certainly acknowledges its mediated history. The slide sequence of the Seattle protest is less a record of what happened in the streets of Seattle on 30 November 1999, a means of setting the mainstream media’s record straight, than a highly conscious play on the ways in which records are made, the ways in which in protest politics becomes consumable as sound bite and sign. We see this in Sekula’s capture of media stereotypes – the ‘hippie’ and the ‘hooligan’ or the bare-chested protestor conjuring up feminist mythologies about bra burning – as well as in his bid for immediacy (fig.7). Sekula walked the streets with his camera. He rejected all the protocols of those institutions designed to keep him separated from the crowd, such as the telephoto lens and press pass. It was also immediacy that Moore coveted in May 1963, insisting that the only way to make the reader ‘feel’ the violence, to become offended by what was happening in the South, was for the photographer – and by proxy, the viewer – to be swept up in the melee.19 ‘I didn’t want to stand back and shoot with a long lens’, Moore once recalled, adding, ‘I wanted to be … where I could feel it. So I could sense it all around me and so I could get the depth that you see with a wide-angle lens. I wanted to see foreground, middle ground, and background. I wanted to get a feeling of what it was like to be involved’.20 For Moore, and perhaps for Sekula, to make a record was not to be on the scene, present. It was to be part of the protest.

Fig.8

Henri Cartier-Bresson

Sunday on the Banks of the River Seine 1938

Published in Henri Cartier-Bresson, The Decisive Moment, New York 1952

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

© Henri Cartier–Bresson/Magnum Photos

Of course, immediacy is the defining characteristic of street photography. It was codified as such in the early 1950s in French photojournalist Henri Cartier-Bresson’s book The Decisive Moment. Published in 1952 as Images á la sauvette (Images on the Run), this collection of photographs, now understood to be the genre’s bible, opened with a short text by Cartier-Bresson propagating a mode of shooting in which there was no separation between the photographer and the world or, to be more exact, no separation between the eye and the camera (fig.8). For Cartier-Bresson, there was instinct and immediacy instead of technology. The Anglophone title of the book encapsulated the difference. ‘Above all’, Cartier-Bresson wrote, ‘I craved to seize the whole essence, in the confines of one single photograph, of some situation in the process of unrolling itself before my eyes.’21 ‘[I]f the shutter was released’, he continued, ‘at the decisive moment, you have instinctively fixed a geometric pattern without which the photograph would be formless and lifeless.’ This was a model of photography ‘on the run’, in which the photographer, to quote Cartier-Bresson again, was ‘on the prowl’ and ready to ‘pounce’.22 It was a model of photography as a means of consuming the world aggressively. It was also a model of photography ‘decisively’ at odds with the photo-essay. ‘If you start cutting and cropping a good photograph’, Cartier-Bresson reprimanded his contemporaries, ‘it means death to the geometrically correct interplay of proportions.’23 In Cartier-Bresson’s world, the eye, not the hand, went to work. In the street, the disembodied eye trafficked in photographs.

Fig.9

Allan Sekula

Waiting for Tear Gas 1999–2000

Tate

© Estate of Allan Sekula

Fig.10

Allan Sekula

Waiting for Tear Gas 1999–2000

Tate

© Estate of Allan Sekula

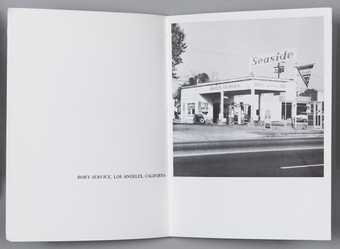

Sekula’s bid for immediacy was firmly at odds with Cartier-Bresson’s model and motto.24 As we have seen, he categorically shunned the single photograph as well as the assumption that capturing ‘the essence’ of any moment, of any event, was possible.25 Sekula’s two photographs of the same woman kneeling in the street, which are paced five slides apart from one another in the sequence, are evidence enough of Sekula’s ban on singularity (figs.9 and 10).26 To be sure, Sekula’s method is no more or less real or accurate than Cartier-Bresson’s. It simply acknowledges what Cartier-Bresson sought to ignore: time. Socialisation, the dialectical relationship between subjects and objects evidenced in Sekula’s photographs, cannot be captured in an instant. It is relational; it takes place over time. The rejection of the single shot went hand-in-hand with Sekula’s rejection of Cartier-Bresson’s appeal to skill: to the ability to capture, in the camera, the perfect, balanced composition. Sekula’s Seattle photographs, like many of the photographs he shot over the years, including those of his family making up the photo-essay Aerospace Folktales 1973, are far from manicured, balanced shots. They are blurry, ‘poorly’ composed and ‘poorly’ lit. Yet Sekula’s photographs are not simply banal or unprofessional. Exaggerating a lack of skill, Sekula outwardly or inversely acknowledges photography’s transformation in the 1960s from a technological form, a means of documentation, to a highly specialised activity.27 Yet unlike Dan Graham and Ed Ruscha, two artists who used photography ‘badly’ or banally, without skill, in their work for the magazine page – Graham’s Homes for America 1967 – and in photo books – Ruscha’s Twentysix Gasoline Stations 1963 (Tate AL00299) – Sekula’s affront to mastery was not an affront to modernism (fig.11).28 Rather, with his blurry, poorly lit, off-kilter photographs, he drew out the very legacies of modernism that postmodernism and conceptual photography repressed: the sustained analysis of the rhetoric of photography. Skill, Sekula teaches us, has a history, and it is one mired in the dialectical labour of photography – handwork and its negation.29 The photograph is both immediate and not. It is both unmediated, and, as Sekula explained in the above-noted recollection about why he took up photography, ‘enigmatic’, ‘misleading’ and ‘reductive’.30

Fig.11

Edward Ruscha

Spread from Twentysix Gasoline Stations 1963

Tate AL00299

© Edward Ruscha

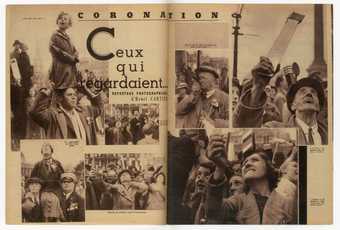

Fig.12

Spread entitled ‘Coronation: Ceux qui Regardaient…’, Regards, no.175, 20 May 1937, pp.6–7, with photographs by Henri Cartier-Bresson

Reproduced in Clément Chéroux, Henri Cartier-Bresson: Here and Now, London 2014, pp.166–7

Fig.13

Unidentified photographer

Photograph published in Dana Yates, ‘Study of Toronto G20 Summit Examines Civil Rights, Role of Social Media’, Ryerson University Magazine, 7 July 2013, with accompanying caption: ‘A crowd of spectators using their mobile phones to capture footage of a burning police car on Queen St. W. in Toronto during the 2010 G20.’

Importantly and perhaps surprisingly this labour is also one of the legacies of Cartier-Bresson’s early practice. A case in point here is Cartier-Bresson’s work for the Communist daily Ce Soir. On 12 May 1937 Cartier-Bresson travelled to London to report on the controversial coronation of King George IV, and his record of the event is striking.31 Determined in part by the fact that the Ce Soir team were not offered a place in Westminster Abbey, were not part of the vetted and legitimate press corps, Cartier-Bresson ignored the main event: the King and his procession.32 Instead he shot the crowds gathered on the streets, crowds who, curiously, were also not watching – at least not directly – the coronation. Like Cartier-Bresson, the public looked away. They rigged makeshift cameras – tiny mirrors attached to sticks – to view the event at or from a distance. The double-page spread of photographs published in Regards, the Communist party’s illustrated weekly, neatly captured and re-mediated the public’s mediations. The reader of the daily looked at a crowd, looking for a King and facing a photographer, who looked away from the King and at the public (fig.12). Present in the street, swept up in or by the event, Cartier-Bresson captured the temporal and spatial paradox of ‘being there’ in the era of mass media. As in the numerous photographs of recent street demonstrations now circulating in which mobile phones are held high above the crowds, to be present, to witness, is also to be one step removed – to be mediated and made into the spectacle (fig.13). Perhaps, as Terri Weissman argues in a subsequent part of this project, it is not the moment or this moment that matters or needs to be recorded. Rather, it is the slippage between the event and its record – or the traffic in photographs.33

Fig.14

Allan Sekula

Waiting for Tear Gas 1999–2000

Tate

© Estate of Allan Sekula

If Sekula filled Waiting for Tear Gas with signs that he was there, present and among the crowds, he also, as the previous essays have argued, filled his photo-essays with signs that the viewer’s relationship to protest is never immediate or complete. There is the juxtaposition between the globe and the street, the whole and the fragment. There are also the moments in the sequence in which Sekula displaces his looking and the viewer’s waiting. In one shot, we see a camera jutting into the frame; in another we see a TV screen, with, despite the blur, a recognisable (at least for US citizens) ‘talking head’ – Ted Koppel reports from Waiting for Tear Gas (fig.14). There is also the single vertical image in the slide sequence (fig.3). Shot from behind, as if the subject was unaware he was subject to the camera, this portrait of a portrait doubles the representation of protest again. As was argued in the opening section of this In Focus project, Sekula loops the media. Importantly, he does so with much more than a camera: Sekula’s technology is neither the eye nor the lens, but rather the slide sequence. It is a means that allows him to work the part against the whole, the hand against the machine and spectacle against the history of photography.