On 30 June 2007 Tate presented a re-creation of the French artist Guy de Cointet’s play Tell Me. The play was staged in Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall in front of a live audience, as part of UBS Openings: Saturday Live, a series of bi-monthly performance events celebrating contemporary cultural practice at Tate. De Cointet’s play, which takes language, abstraction and the perception of reality as its subject, was performed for the first time in Los Angeles in 1979. Tell Me disregarded the structures of traditional theatre in favour of a highly stylised aesthetic and a proliferation of abstract visual symbolism, both of which rendered the on-stage action completely fantastical and dissolved any possibility of narrative coherence. Nearly three decades later the presentation of Tell Me at Tate was performed by the same actresses who starred in the original production – Denise Domergue, Jane Zinagle and Helen Mendez Berlant – and worked from De Cointet’s original set design, script and directions.

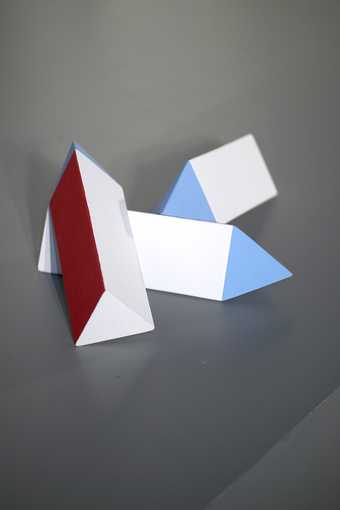

The set was a domestic interior, consisting of fabricated white angular furniture and a selection of brightly coloured minimalist objects. It was occupied by three female characters who took part in a series of absurd conversations, while interacting with the props and each other in bizarre and unexpected ways. At Tate the audience received a short piece of text before the play began, written by De Cointet as an introduction to the original 1979 performance. It set the scene of Tell Me in the late afternoon, at a house belonging to a woman called Mary on the banks of the Sacramento River in Northern California. The text detailed that Mary was preparing to spend the evening with some of her best friends: ‘Michael, Olive, and the elusive Mark’, the last of whom never makes an appearance. Written in the first person, De Cointet’s introduction described his particular interest in the performance, which lay in ‘the way these young women behave, talking and listening to each other, how they see and perceive their surroundings’.

Once the play began, however, it became clear that it had no obvious plot. Rather, the audience was tasked with following the women’s conversation as it turned sharply through a diverse range of topics, unconcerned with resolving one subject before turning to the next. Modelled on a plethora of vernacular sources, including soap operas, melodramas, fashion magazines and eavesdropped conversations, the dialogue often made little sense and shifted in tone from the dramatic to the informative. Serious discussions about art and mythology mingled with gossipy tit-bits, random outbursts and a series of obscure ramblings about cigars, snails and hammers. As the curator Cornelia Butler has noted, De Cointet himself ‘was never specific about whether his texts could be decoded at all. He was interested in the slippage and the possibility of a fixed meaning.’1

The props also destabilised the realism of the narrative. Each object held a significance for the play’s characters, which was illegible to the audience. A grid of letters on a white backdrop was said to represent an intricate map, which the women claimed marked the location of King Solomon’s mines. A green and white cut-out on the wall was an extravagant new painting, which Michael, ignoring its aesthetic qualities, admired as being ‘soft’. A block of orange cubes on the table were a precious book, whose sentences were tragically broken – with ‘one word beyond repair’ – when Mary accidentally knocked it over. Three arrow-shaped objects to the side of the stage were trumpets used by Olive, not as musical instruments, but as healing implements for Michael’s sore leg. Indeed, as the play progressed, language and meaning increasingly gave way to nonsensical action and translation, with the three female characters often replacing words with abstract and comical sounds.

As Butler has observed in Tell Me, ‘there is no subject or eventual resolve to the character’s actions. Structure itself becomes active and purposeful within the narrative and no communication is articulated in a manner that sticks.’2

The crux of the play lay in the expectation and the subsequent failure of a coherent structure or plot, exemplified by the male character Mark, who though consistently referred to both in the written introduction and throughout the play never materialises. The comedy, or perhaps frustration, evoked by such an unfulfilled promise was the primary means of operation in the play, which ‘in the end is about nothing’.3

As suggested by the title, Tell Me evoked a yearning for a secret knowledge that ultimately would never be revealed.

Clare Gormley

May 2016