Nowhere and Everywhere at the Same Time by William Forsythe was performed in front of a live audience on the 30 April and 1 May 2009, in Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall. The dance piece was part of Focus on Forsythe, a two-week retrospective of the renowned American choreographer’s work, organised by Tate in collaboration with Sadler’s Wells, that comprised performances, installations and film events held at Tate Modern, Sadler’s Wells and other locations around London, including the club Fabric in Farringdon, South London Gallery in Peckham and a disused railway shed in Kings Cross.

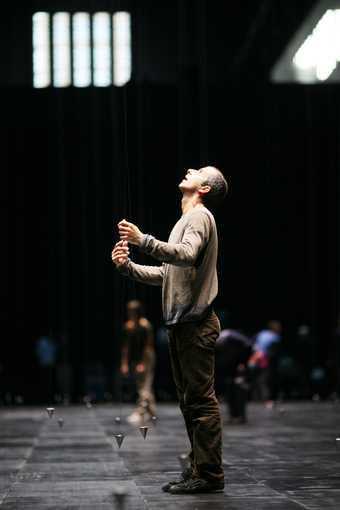

For Nowhere and Everywhere at the Same Time, Tate’s Turbine Hall was filled with dozens of metal pendulums suspended from wire rope. These pendulums hovered centimetres above the ground; the field of plumb-lines carved the space of the hall into narrow vertical chutes. It was within and among these delicately framed channels that the performance was both devised by Forsythe and performed by the seventeen dancers of the Forsythe Company. The dancers used the pendulums as catalysts for movement, their bodies reacting to the objects, and each other, as they moved through the field. Forsythe has commented that the work’s choreography is ‘based on observations; so the dancers are observing the room, observing each other, and producing conclusions or expressing their observations’ through movement.1 These observations were however not exclusively visual in nature. The work’s title, Nowhere and Everywhere at the Same Time, is a direct reference to the blind French resistance fighter Jacques Lusseyran, who used the phrase to describe the boundless mental canvas upon which he envisioned forms and composed ideas; allowing him ‘to see topographies and project strategic movements of groups of people’ without the aid of sight.2 It was in the manner of such an imagined inner landscape that Forsythe conceptualised this work for Tate, proposing the pendulums as ‘choreographic objects’ through which his dancers would physically and mentally ‘transition from one state to another’.3 Additionally, the work’s title and the installation itself referred to the omnipresent field of gravity, as both a phenomenon so ordinary as to be taken for granted and forgotten and a crucial natural force by which our every movement is determined.

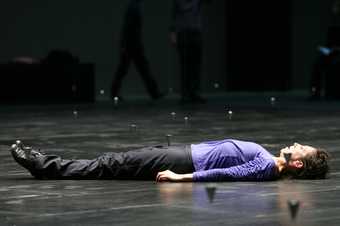

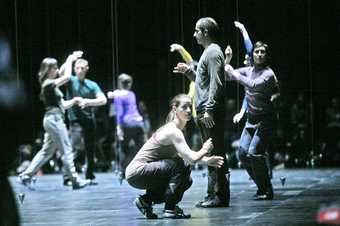

The performance’s fluctuations multiplied, as the audience could walk around the exterior of the pendulum field, observing the dancers from different perspectives as they flitted between these real and imagined states of being. By conceiving Tate’s Turbine Hall as both ‘nowhere and everywhere at the same time’, this performance sought to unleash the kinetic and metaphorical potentials of the space, with Forsythe’s dancers on a persistent enquiry, navigating the structures and powers of their external and internal environments at every turn. At times during the performance the dancers’ bodies seemed to reverberate against or be drawn to the pendulums, their bodily movements inflected by physical contact with the objects. In other instances the dancers worked to avoid the pendulums, threading their limbs and torsos through the space. While one dancer lay still beneath a pendulum, sucking in his stomach so that it may breeze gently over him, others ran energetically through the different sections of the installation or purposefully knocked and swung the hanging cords. Periodically chaotic ripples of action developed, so that one performer’s movements would seem to attract or repel others; lone dancers forming into groups before breaking apart again and dispersing throughout the space in movements ranging from jerky and staccato to smooth and meditative. An otherworldly score composed by Thom Willems played throughout the Turbine Hall, its mixture of digital tones and warped instrumental sounds reflecting the diversity of movements enacted by the dancers.

Clare Gormley

July 2016