At the death of Sir Edwin Manton, the great benefactor of the Tate Britain, on 1 October 2005, one of the mysteries he left behind was the provenance of the sketch for John Constable’s The Glebe Farm, c.1830 (Tate T12293), on loan to Tate from 1998, before being transferred to the gallery as a gift in 2006.

The Glebe Farm canon

When it was rediscovered in the mid 1990s, Sir Edwin’s picture joined the canon of Constable’s Glebe Farm paintings. The subject, a cottage and lane scene with the tower of the Langham church, Essex, was a favourite of the artist. In December 1836 he wrote to C.R. Leslie: ‘Sheepshanks means to have my Glebe Farm, or Green Lane, of which you have a sketch. This is one of the pictures on which I rest my little pretensions of futurity’.1

There are five versions currently known. The earliest is an oil sketch in the Victoria and Albert Museum (No.161–1888, fig.2), given by the artist’s children in 1888. Undated, it is generally thought to have been painted between 1810 and 1815.2 The sketch is almost certainly the basis for the later pictures, but lacks the church tower.

Fig.2

John Constable

Church Farm, Langham c.1810–15

Isabel Constable; given by her in 1888

© V&A Images/Victoria and Albert Museum, London

The first reference to the subject by Constable seems to be in a letter written to his dear friend, Archdeacon John Fisher, on 9 September 1826:

My last landscape [is] a cottage scene – with the Church of Langham – the poor bishops first living – & which he held while at Exeter in commendamus. It is one of my best – very rich in color – & fresh and bright – and I have ‘pacified it’ – so that it gains much by that in tone & solemnity.3

The bishop was John Fisher, Bishop of Salisbury, the archdeacon’s uncle and a loyal mentor and patron of Constable, who had died the previous year. The painting was exhibited at the British Institution in 1827, (314, The Glebe Farm), where it sold to George Morant, in whose collection it remained until 1832. It is now in the collection of the Detroit Institute of Arts (No.64.117).

Fig.3

John Constable

The Glebe Farm 1827

Gift of Mrs Joseph B. Sclotman

Photo: © 2005 The Detroit Institute of Arts

Chronologically, the Manton Glebe follows the Detroit version, upon which it was modelled. It was executed around 1830 to be used by David Lucas to produce a mezzotint of the subject for Constable’s book, English Landscape Scenery. Presumably this was necessary because Morant’s picture was unavailable. Lucas made good progress on the mezzotint during 1831 and all was in order to include it in the fifth and last instalment of Constable’s book. Sometime prior to 4 November 1831, however, things went awry. It seems Lucas made some changes to the mezzotint without consulting Constable and the results were disastrous. Constable was greatly agitated and wrote to him, ‘I could cry for my poor wretched wreck of the Glebe Farm – a name that once cheered me in progress – now become painful to the last degree.’4 The Glebe Farm mezzotint based on T12293 was abandoned at Constable’s insistence (see fig.4).

Fig.4

David Lucas after John Constable

The Glebe Farm 1832

The British Museum, London

It is an indication of Constable’s admiration of the subject that a new mezzotint of The Glebe Farm was underway by the end of 1831. He may, in fact, have considered changing or replacing Lucas’s original work as early as 22 August 1831, well before disaster struck. In a note to Lucas, Constable wrote: ‘Leslie will prefer the Glebe Farm & I think his to be engraved. I wonder if the present Glebe Farm plate would work into a new composition of the same.’5

Leslie’s picture (Tate N01823) is an unfinished version of the subject that Constable gave to C.R. Leslie, probably in 1830.6 While retaining the general structure of the earlier versions, Leslie’s picture shows the beginning of a vignette in the foreground that, in prospectuses for English Landscape Scenery, would be called ‘girl at a spring’.7 The vignette had been started; the log and pitcher are in place, but the girl is not. The 1860 catalogue of Leslie’s sale at Foster’s told the story:

Mr. Leslie saw Constable at work on this picture, and told him that he liked it so much he did not think it wanted another touch. Constable said, ‘Then take it away with you that I may not be tempted to touch it again.’ The same evening the picture was sent to Mr. Leslie as a present8 (see fig.5).

John Constable

The Glebe Farm

(c.1830)

Tate

The final version of the subject, Tate N01274 (see fig.6), completes the foreground scene. It seems to have been underway by the end of 1831 and it was certainly finished by 1832. When the final instalment of English Landscape Scenery was published in the summer of that year, it included the new Glebe Farm mezzotint based on this picture.

John Constable

The Glebe Farm

(c.1830)

Tate

Despite the frustrations he had encountered in the preparation of his book, Constable began to think about adding an appendix to it and revisited the abandoned mezzotint of The Glebe Farm, based on T12293, for possible inclusion. On 2 October 1832, he wrote to Lucas, ‘I have added a “Ruin”, to the little Glebe Farm – for, not to have a symbol in the book of myself, and of the “Work” which I have projected, would be missing the opportunity.’9 The ‘Ruin’ was published posthumously as Castle Acre Priory (see fig.7). In all likelihood, during this tranformation from the abandoned Glebe Farm mezzotint (fig.4) to the Castle Acre Priory mezzotint, Constable experimented with T12293, trying out variations to the picture that included not only the spire added to the top of the tower and the addition of a rainbow, but the conversion of the tower into a windmill; the vanes are still perceptible.

Fig.7

David Lucas after John Constable,

Castle Acre Priory c.1832

Published by Henry G. Bohm, London, 1855

Collection of the author

At least one other Glebe Farm belongs to the canon, though its whereabouts is not known. As will be discussed in detail below, Constable’s 1838 sale at Foster’s included three Glebe Farm pictures, two of which are identifiable as Tate T12293 and Tate N01274. The third version has yet to reappear. As will be demonstrated, there is good reason to identify this as the picture purchased by W.H. Carpenter in Lot 13. If this is so, and it continued in Carpenter’s possession, as seems likely, we may deduce from his 1867 sales catalogue that it, like T12293, was a study for the subject (for a more complete discussion, see below).

The provenance of Tate’s Glebe Farm sketch

Tate’s Glebe Farm sketch (T12293) came to light after the publication of Graham Reynolds’s first volume of Constable’s catalogue raisonné, The Later Paintings and Drawings of John Constable (1984), necessitating its inclusion in The Early Paintings and Drawings of John Constable (1996). It was assigned number 27.9A. The provenance, as published, extended back to Emory Ford in 1914.10 It is now possible to push that date back to Constable’s sale at Foster’s on 16 May 1838, as part of Lot 10, where Williams purchased it. The chain of ownership can then be traced through George Oldnall of Redhill, Worcester; Thomas Woolner, Edwin Bullock of Birmingham, Handsworth, and Octavius Coope of Brentwood, Essex, from whose sale it was purchased by Colnaghi. Colnaghi then sold it to Scott & Fowles, New York. It is assumed Emory Ford of Detroit, Michigan, purchased the picture from Scott & Fowles, though to date there is no direct evidence.

The keystone for this extended provenance is the Octavius Coope sale at Christie’s on 6 May 1910. Lot 8, illustrated in the catalogue, is entitled The Vicarage, and both visually and by measurement (18¼” x 23¼”) is readily identifiable as Tate’s Glebe Farm sketch (see fig.8).

Fig.8

John Constable

The Vicarage

(As published in the Christie's catalogue, O.E. Coope sale, 6 May 1910, Lot 8)

Ingalls Library, The Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, Ohio

The picture was purchased by Colnaghi for 700gns. [£735]. It appears in the P. & G. Colnaghi & Co. stock book as No.1972, Castle Acre Priory. Colnaghi’s records indicate that they did some minor repair and reframed the picture. It was sold to Scott & Fowles on 24 June 1912 for £1,200.11

The Coope catalogue of 1910 helps to trace the picture back to its origins, listing Edwin Bullock and George Oldnall as its prior owners and providing information about its appearance at the ‘Century of British Art’, at the Grosvenor Gallery, 1888. Although it is listed as The Vicarage in the Coope catalogue, the annotated version at the Cleveland Art Museum has The Manor House pencilled in, as well a note about it being engraved by D. Lucas (see fig.9)12

Fig.9

Christie's catalogue, O.E. Coope sale, 6 May 1910 (Lot 8)

Ingall's Library, The Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, Ohio

This information may have been shared in the sales room and helps to identify the picture in the collection of Edwin Bullock, an ironmaster and noted collector in Handsworth, Birmingham. His 21–23 May 1879 sale was promoted by Christie’s as being ‘well known as one of the best in the Midland Counties; it was commenced by the late owner about forty years ago, most of the works were obtained direct from the painters.’13 The sale realised £42,700.14 There was no Vicarage in the Bullock sale, but a picture named The Manor House was Lot 83. It was purchased by Agnew’s and their stock books confirm that they were acting as agent for Octavius Coope, buying the painting for 135 gns. [£141 15s] and transferring it to Coope the same day.15

The Coope catalogue identification of the picture as The Vicarage harks back to the sale of George Oldnall of Redhill, Worcester. Oldnall was a member of the Worcester Institution for the Promotion of Literature, Science, and the Fine Arts founded around 1834, and served on the Sub Committee of the Fine Arts from its beginning.16 This is the group that organised the Worcester Athenaeum exhibits of 1834, 1835, and 1836, in which Constable participated.17 Oldnall was almost certainly present when Constable presented his lectures there in 1835. By the time of Oldnall’s sale at Christie’s on 16 June 1847, he had amassed a nice collection of paintings. Included among them were eleven listed as being by Constable:

- 103 A study of trees

- 104 A meadow and brook scene

- 105 A study of trees – upright

- 106 Willy Lot’s [sic] cottage

- 107 A road scene, with trees

- 108 A view of Dedham – harvest scene

- 109 The Vicarage – painted with fine effect

- 110 Yarmouth Jetty – painted with admirable effect

- 111 Dedham Vale with a group of Cows – capital

- 112 London, from Hampstead Heath

Lot 109, The Vicarage, sold to Woolner for £27 6s.18 The likelihood is that the purchaser was Thomas Woolner, then a struggling young artist in London, who was about to leave for an adventure in Australia to seek his fortune in mining. During his life, Woolner developed a reputation as an art trader, which his daughter later addressed in her biography of him.19 He would, in fact, become the owner of another version of The Glebe Farm that for many years was considered to be authentic, though it now is thought to be a copy after Lucas’s published mezzotint. The picture was in his sale in 1913 and is now at the Barber Institute.20 On Woolner’s return from Australia he resumed his art career, becoming a renowned sculptor, a Royal Academician, and one of the seven founders of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.

Woolner may have played some role in the name changes the picture endured. Why did Coope, who had purchased the painting as The Manor House, come to call the work by its previous title The Vicarage? How did Coope learn of its provenance back to Oldnall, which was included in his sale catalogue, but not in Bullock’s?

The answer probably lies at the Grosvenor Gallery Winter Exhibition in January 1888. There were two Glebe Farms at that exhibition. Exhibit number 46 was the Woolner (Barber Institute) picture. Mrs. O.E. Coope lent exhibit number 98, called The Manor House in the exhibition catalogue, the name it bore at the Bullock sale. It is reasonable to think that Woolner would have recognised the painting and informed the Coopes of its former name and ownership.

The provenance of the Tate sketch, then, seems quite certain, from the current owners back to George Oldnall; its paper trail is strong and Woolner may have even been an eyewitness!

But where did Oldnall get the painting, and how is it to be traced back to Constable?

Constable’s sale

On the second day of Constable’s sale at Foster’s, 16 May 1838, there were three paintings identified as The Glebe Farm, in Lots 10, 13, and 70. The entries in the catalogue read:

- 10 Three – The Glebe Farm; Salisbury, and one other

- 13 Two – Salisbury Cathedral and the Glebe Farm

- 70 The Glebe Farm. Exhibited 1835

The painting in Lot 70 is Tate N01274. It was bought by C.R. Leslie for Constable’s eldest son, John Charles, and stayed with the family until donated to the National Gallery in 1888 in the name of Isabel, Lionel, & Maria Louisa Constable. It was exhibited at Worcester in 1835, and in 1863 was offered at auction at Christie’s by the Constable children, but bought in.21

Reynolds suggests that Tate T12293 was part of Lot 13 in Constable’s sale, based primarily on the fact that the price paid for the lot was nearly eight times higher than that for the three pictures in Lot 10. To Reynolds this was an indication of finer quality.22

Lot 13, The Glebe Farm and a Salisbury Cathedral, sold for £24 3s to Carpenter, whom Reynolds presumes to be William Hookham Carpenter, allowing, however, that it may have been his father James.23 Whichever Carpenter was present at the sale, at least one of his purchases, The Cenotaph (Lot 71), was in the possession of the Constable family in 1888, when it, too, was part of their bequest to the National Gallery. That led R.B. Beckett to the possibility that ‘William Carpenter was one of the group of Constable’s friends who joined together on this occasion to buy in some of the finest works on behalf of the orphaned children. He was already on the committee that arranged for Constable’s The Cornfield to be bought for the nation.’24 There is no indication, however, that the two pictures in Lot 13, being studies, were among these charitable purchases. The Salisbury Cathedral, it is generally agreed, was in William Hookham Carpenter’s 16 February 1867 sale at Christie’s as Lot 77. It sold to Halstead, a dealer, for £63, and now hangs in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC.25

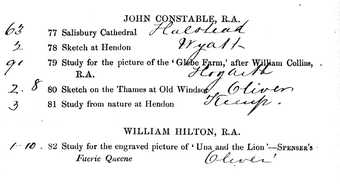

Carpenter’s sale also included a Glebe Farm, offered as Lot 79. Although it would seem reasonable to conclude that this was the other picture in Lot 13 of Constable’s sale, a typographical error in the catalogue and subsequent pencilled annotations in an existing copy have raised doubt about that and about the authenticity of this picture. The confusion was caused by a misprint in the catalogue for Carpenter’s sale. The catalogue entries were divided by artist, using a subheading of an artist’s name followed by the various works by that artist. The error occurs in the Constable section, and involves him and William Collins, R.A.

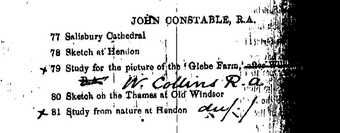

As originally printed, the description for Lot 79 reads: ‘A study for “The Glebe Farm”, after William Collins, R.A.’ Lots 80 and 81, which appeared also to be by Constable, followed this entry (see fig.10).

Fig.10

Christie’s catalogue, William Hookham Carpenter sale, 16 February 1867

(Lots 77 to 82, as originally printed)

National Art Library, Victoria and Albert Museum, London

On reading this entry, one would, at best, conclude that Constable had copied The Glebe Farm from Collins, a proposition that, on its face, is ridiculous. At worst, one might conclude that William Collins had painted this study for The Glebe Farm, which George Redford’s compilation of nineteenth-century art sales, in fact, does when recording Carpenter’s sale.26

There is a certain irony here. On 15 February 1830, Constable wrote to W. H. Carpenter, who was married to the sister of Collins’s wife, ‘You do me an injustice in supposing that I despise poor Bonnington. I despise no man – but Collins the Royal Academician.’27 Constable would not have been pleased had he seen the entry in the Christie’s catalogue.

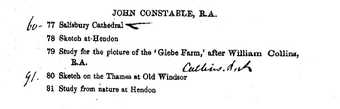

Fortunately, existing annotated copies make it clear that there was to have been a new subtitle for William Collins, following Lot 79, and that Lots 80 and 81 were by Collins. But the confusion continued around the secondary clause in the description of Lot 79.

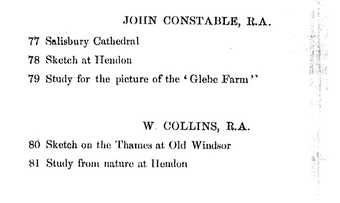

In the version of the catalogue at the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Massachusetts, the clause is left intact, and a subtitle, ‘Collins R.A.’, simply penciled in below (see fig.11).

Fig.11

Christie's catalogue, William Hookham Carpenter sale, 16 February 1867

(Lots 77 to 81, as annotated by simply adding 'Collins R.A.' as a subheading)

Clark Art Institute Library, Williamstown, Massachusetts

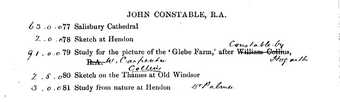

Another annotated copy, at the National Art Library at the Victoria and Albert Museum, adds the subtitle, crosses out most of the final clause, and replaces it with a cryptic ‘after W. Collins Constable by W. Carpenter’ (see fig.12). It was this annotated catalogue that led Reynolds to the conclusion that Lot 79 was a copy painted by William Carpenter, W.H. Carpenter’s son, and that there ‘has at one time been in existence a good copy of The Glebe Farm by him, though it is not known which version it reproduced.’28

Fig.12

Christie's catalogue, William Hookham Carpenter sale, 16 February 1867

(Lots 77 to 81, annotated by amending the final clause in addition to adding 'Collins' as a subheading)

National Art Library, Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Because Tate T12293 was in the Oldnall collection by 1847, Reynolds’s later identification of it with Lot 13 purchased by Carpenter at the artist’s sale is dependent on his earlier assertion that the Glebe in the Carpenter sale was a ‘good copy’. Two surviving catalogues of the sale challenge this conclusion.

The first is the official record in the Christie’s archive. In it, the ‘after William Collins, R.A.’ is struck and a new subtitle, ‘William Collins, R.A.’, is inserted (see fig.13). There is no mention of ‘W. Carpenter’. The implications of this redaction are significant. By simply striking the final clause, the Christie’s copy suggests that the error was merely typographical.

Fig.13

Christie's catalogue, William Hookham Carpenter sale, 16 February 1867

(Lots 77 to 81 in the auctioneer's catalogue at Christie's).

The final clause is struck, and the heading 'W. Collins R.A.' is inserted before Lot 80

Christie's Archive, London

The archived catalogue is the ‘first’ copy, the official record of the auction. According to Christie’s archivist Jeremy Rex-Parkes, ‘It is the auctioneer’s book, which was annotated with the price and buyer’s name actually in the saleroom. So it is the absolute original and it certainly bears witness to the actual sale, with the clerk’s hand poised with a quill to annotate it. So what could be better!’29

This interpretation of the Christie’s Carpenter sale catalogue is confirmed by a corrected, published edition at the Frick Art Library, New York, illustrated in fig.14. In it the Constable and Collins sections have been re-typeset following the pattern of the annotated catalogue in the Christie’s archive. A physical examination by Jacqueline Rogers, Reference Associate at the Frick Library,30 indicated that this copy was, in fact, a new edition, and not replacement pages tipped into the original.

Fig.14

Christie’s catalogue, William Hookham Carpenter sale, 16 February 1867

(Lots 77 to 81 in the revised edition of the Christie’s catalogue)

Frick Art Reference Library, New York

Publishing a corrected edition after the auction was concluded is quite out of the ordinary and the fact that the auction house absorbed the expense of the reprinting is a clear indication that The Glebe Farm in Lot 79 was thought to be authentic at the time. It also suggests that Christie’s was under some pressure in the matter.

One source of this pressure may have been Joseph Hogarth, the purchaser of the painting. He was a framer, printseller, and picture dealer of some note. When Charles Golding Constable, the artist’s son, retired to London after a naval career abroad, he sent a number of his father’s paintings to Hogarth in 1865 ‘for mounting or framing, and, in some cases, cleaning and restoration’.31 At a time when the market was being inundated with fraudulent or misattributed Constable pictures, Hogarth, as a dealer, would certainly have wanted a ‘clean’ catalogue to show to a potential buyer, and may have requested the revision.

Another source may have been C.G. Constable himself. After his retirement from a naval career in 1860, he returned to London and became what Parris and Fleming-Williams called a ‘watch-dog’ regarding his father’s work. He frequented galleries, exhibitions, and sales, and made notes in his diary of the ‘shams’ he had seen,32 occasionally denouncing what he thought were fraudulent pictures in the press. If the Carpenter sale were among these visits he would have seen the error in the catalogue and could hardly have been silent about its implication that his father may have copied Collins.

If the corrected edition of the catalogue shows that Christie’s had confidence in the authenticity of the picture, the auction results indicate that those in attendance agreed. The picture brought £91. It was a high price, suggesting a study of some importance. It was nearly fifty per cent higher than the price paid for the Salisbury Cathedral in Lot 77, which is known to be an impressive work. It also brought more than any of the paintings by Mrs Margaret Geddes Carpenter, W.H. Carpenter’s wife, a noted portrait painter who had exhibited often at the Royal Academy. Several of her paintings, many of them finished, were in the sale and sold in the range of £1 to £29 8s. William Carpenter, named in the annotated V&A catalogue as the Glebe Farm ‘copyist’, was also represented in the sale. He was an accomplished artist and had also exhibited at the Academy with some success. Of his seven works in the Carpenter sale, all but one brought less than £4, the other bringing slightly more than £20. It is unlikely that a ‘study … after Constable’ by him would have fetched such a strong price, especially from an experienced dealer such as Hogarth.33

The auction results, along with the facts that Carpenter bought Lot 13 at the artist’s sale in 1838 and that the Salisbury Cathedral bought in the same lot seems to have stayed in his collection for nearly thirty years, lead to the conclusion that The Glebe Farm purchased in the Constable sale stayed in Carpenter’s collection until 1867, when it was sold to Hogarth.

Since, at that date, Tate T12293 had passed through the collection of George Oldnall and belonged to Edwin Bullock, it cannot have been the picture purchased by Carpenter, as Reynolds suggested. It is much more likely that Tate T12293 was The Glebe Farm in Lot 10 bought by Williams, one of three pictures purchased in that lot for £3 15s34

Which Williams?

John Constable would have been quite at home at Foster’s sales rooms on the second day of his 1838 sale. Many of the thirty-four successful buyers are readily identifiable as family, old friends, fellow artists, patrons, or dealers. Even his solicitor, H.D. Haverfield, bought two lots containing fifteen pictures. Others are harder to place. Williams is among these.

Parris and Fleming-Williams have identified many of the participants and their relationships to Constable, most with a high degree of certainty. Of Williams, however, they could only suggest that he was ‘presumably also a dealer’, based, it seems, on the number of pictures he purchased.35

Williams was, in fact, one of the most active participants in the sale, purchasing a total of eight lots, second only to the dealer Samuel Archbutt, who purchased nine. The Williams lots contained twenty pictures, the highest number purchased by a single buyer. He was not, however, a big spender. His total outlay was £23 10s 6d, or an average of £1 3s per picture, one of the lowest averages at the sale. This compares to Archbutt’s average of £18 2s for the fourteen pictures he purchased, and the £37 12s average for the seven pictures purchased by W.W.D. Tiffin, another dealer active at the sale, a number that would be even higher if the pencil sketch in Lot 85 were omitted.

Williams’s buying focused on studies and sketches in multiple lots:

- Lot 10 Three – The Glebe Farm, Salisbury, and one other;

- Lot 11 Three – View of a Gentleman’s House and Park in Berkshire, Sea-Shore at Brighton, and a Study of Trees;

- Lot 21 A Landscape, study from nature;

- Lot 32 Three sketches;

- Lot 34 Salisbury Cathedral, the Lock, and one other;

- Lot 37 Sketch of Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadow;

- Lot 47 Five – Weymouth Bay, and four others

- Lot 86 Sketch, Peter Martyr.

The most expensive of these was the sketch of Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows, purchased for £6 10s. Reynolds tentatively identifies this as the full-size study in the collection of the Guildhall Art Gallery, London.36

While it may not be possible to identify Williams definitively, the presence of The Glebe Farm from Lot 10 in the George Oldnall collection offers an avenue of speculation. That provenance and a childhood memory combine to build a circumstantial case that Williams may be Oldnall’s friend, neighbour, and fellow Constable admirer, Edward Leader Williams of Worcester.

Oldnall and Williams served together on the Sub Committee of the Fine Arts of the Worcester Institution, where Williams acted as Honorary Secretary. In this role, he seems to have had responsibility for corresponding with the artists, a job for which he must have had some talent. Royal Academicians whose works appeared in the 1834 exhibition included Chalons, Etty, Howard, Jones, Pickersgill, Phillips, the Reinagles, James Ward, and Constable – an impressive list. Constable sent two pictures, Salisbury Cathedral from the Bishop’s Grounds and Landscape – a Barge passing a Lock on the Stour.37

Edward Leader Williams, born about 1803, and his wife, Sarah Whiting, born 1801, settled in Worcester soon after they were married in 1827. Edward had established business as an ironmonger, his father’s trade, and they lived at 94 High Street, probably in the residence above his shop.38

As their family grew, they sought larger quarters. Sometime between their fourth child in 1832 and their fifth in 1834, they rented Bromwich Villa, on Bromwich Lane in St John’s on the west bank of the River Severn.39 It was a time of transition in Williams’s career. He was listed as ironmonger again in the directories of 1835 and 1837, but by 1835 he was calling himself an engineer. In that year he began to promote a plan to extend the navigability of the Severn through the use of locks and weirs. A commission was formed and he was named ‘resident engineer’.40 This interest in river-borne commerce was surely a point of commonality between him and Constable.

From an undated letter written to him by Constable following the 1834 exhibition, we learn of Williams’s appreciation of Constable’s work, and particularly of The Lock. Beckett attributes this to a ‘technical interest in Constable’s depiction of a “navigator” doing his work on another navigable river.’41 Constable wrote to thank Williams for his interest and kind words: ‘That you should really have taken the trouble to visit my “Lock” so often is a sincere compliment to the picture.’42

A friendship between Williams and Constable seems to have grown by the spring of 1835. In a letter dated 27 April 1835 we learn that Williams had visited Constable on one of his trips to London and attempted a second visit,43 and that, sometime prior, Constable had sent him a complimentary copy of his English Landscape Scenery. The letter also refers to a commitment Constable had made to go to Worcester that autumn, following the Athenaeum exhibit, to deliver the lecture he had first delivered at Hampstead in the summer of 1833. Constable travelled to Worcester on 5 October 1835 and stayed with Williams at Bromwich Villa. It was fortunate that Constable loved children so much, for there were then six children under its modest roof. Around 1846 the family would move back to the east side of the Severn to Diglis House, a large home near the cathedral, which they probably also rented.44

By 1838, the number of Williams children had grown to seven, aged 1 to 8 years, with, perhaps, another on the way.45 Edward Leader Williams was still establishing a career as an engineer and the family continued to live in modest quarters of Bromwich Villa in St John’s. In short, he was a young man with many obligations and limited means. The purchasing pattern of the Williams at Constable’s sale is consistent with just such a person, and, because of the prices at the auction, he was able to take home a number of pictures for a very low price. But is there any other evidence that Edward Leader Williams was the buyer? Perhaps.

Lord Windsor, in one of the first of the modern biographies of Constable, retells a story related to him by B.W. Leader, the second of Edward Leader Williams’s sons. Leader, né Benjamin Leader Williams, was a Royal Academician who transposed his second and last names to avoid confusion with other Williamses who were artists. In his interview with Windsor he recollected that,

‘Salisbury from the Bishop’s Meadows’, the large upright ‘Lock’, the ‘Glebe Farm’, and ‘Flatford Mill’ were among the pictures he [Constable] asked my father to hang up in our dining-room for a time, he not having room in his house in town for them.46

Beckett wrote that the reminiscences of Leader must be ‘taken with a considerable degree of caution’. He continues,

for Mr Leader was only four years old when Constable visited Worcester in 1835, and a child’s memories can be fallacious in after-life, as may be seen with Charles Constable. The reference to Salisbury Cathedral confuses the titles of two separate pictures; the other three pictures mentioned were exhibited at Worcester in different years; and it is difficult to believe that anyone could identify with certainty a picture last seen in childhood after a lapse of half a century or more.47

Interestingly, most of the inconsistencies in B.W. Leader’s story disappear if the hypothesis that his father brought several pictures home from Constable’s sale is applied. Though they were not exhibited in Worcester at the same time, three of the paintings Leader mentioned did bear the titles, with slight variation, of those purchased by Williams in Lots 10, 31, and 34. Among them was The Lock, a version, presumably a sketch, of the picture so admired by Edward Leader Williams.

We also learn that these four pictures were part of a larger group held in the Williams home. This would eliminate the 1834 exhibition to which Constable sent only two pictures, and probably that of 1835 with its five. Constable sent nine pictures to the 1836 exhibition, but apart from Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows, the titles have no correlation with Leader’s recollection. That these were four pictures chosen from the twenty Williams purchased at Foster’s is a reasonable possibility.

Finally, Leader’s memory was that the pictures were in the Williams home ‘for a time’. His explanation that Constable had asked Williams to keep the pictures because he had no ‘room in his house in town for them’ is so uncharacteristic of Constable as to be unbelievable. The memory of them being in the house only temporarily, however, is consistent with Williams having sold the pictures or given them away, including The Glebe Farm, later found in his friend George Oldnall’s collection as The Vicarage. Interestingly, two paintings entitled Study of Trees were also included in the Oldnall sale, a name that appeared in Lot 11 of the Constable sale, also purchased by Williams.

It is possible, then, that Leader’s memory came from a time when he was seven years old, not four, and that, if slightly befuddled, it was essentially correct. The pictures had been on his dining-room walls for a time, placed there on his father’s return from London in 1838.

While this is not hard evidence that Edward Leader Williams was a participant in the Constable sale, it is certainly sufficient to entertain the idea as a viable possibility and encourage further research.48

Conclusion

The naming and renaming of Constable’s works is an historic problem for researchers, but occasionally, as with Sir Edwin Manton’s Glebe Farm, there is an opportunity to decipher the clues and uncover the progression of names and owners. Thanks to the discovery of the painting in the Coope sale of 1910, it has been possible to trace the picture back to the artist’s 1838 sale as part of Lot 10, sold to Williams, and subsequently owned by George Oldnall, Thomas Woolner, Edwin Bullock, Agnew’s, the Octavius Coopes, Colnaghi, and Scott & Fowles, before joining the previously known provenance leading to the Tate Gallery. It has been called by the names of The Vicarage, The Manor House, and Castle Acre Priory, before finally and rightly returning to the name that Constable gave it in the beginning, The Glebe Farm.

Epilogue

The Glebe Farm became a popular subject for imitation. The existence of a sizeable number of copies is most often linked to its availability as a mezzotint included in Constable’s English Landscape Scenery, engraved by David Lucas and published by Constable in 1832, with minimal success, and again by Bohn in 1855, with, presumably, wider distribution. An examination of the known copies, however, reveals that nearly all seem to have made their first appearance after 1888, the year that the family gave the picture upon which the mezzotint was based to the National Gallery,49 making it available for public viewing. In 1889, Dowdeswell & Dowdeswell Galleries published an engraving of the picture by David Law,50 and in 1892 another engraving by Dawson was published in the magazine Portfolio.51 In the ensuing years several versions of the painting found their way to the marketplace, including three that went through the collection of James Orrock.52

At present, only three Glebe Farm copies have known dates before 1888. Thomas Woolner exhibited the Barber Institute Glebe in Edinburgh in 1886. There are also two versions at the Louvre: RF304, a dark picture based on the mezzotint, purchased at the March 1881 sale of John W. Wilson; and RF40, entitled L’Arc-en-Ciel, given to the museum by Wilson in 1873 (fig.15).

Fig.15

Artist unknown

L’Arc-en-Ciel

Musée du Louvre, Paris

In 1907, Percy Moore Turner wrote a review of Constable’s pictures at the Louvre.53 [ RF304 was hung so high that Turner, though sure it was not by Constable, would not venture to name the forger. About the other, however he had some definite opinions. Though it is now obvious that L’Arc-en-Ciel is a copy of T12293, the sketch was not known at the time Turner was writing:

The Rainbow, obviously founded on the Glebe Farm of the National Gallery, has several additions which in themselves would be suspicious if everything else were favourable; but the flat and opaque brushwork of the church on the hill, and the sky, are characteristic traits of that able and prolific forger of Constable and Turner – James Webb. The work is, however, in a measure clever, and closely approaches Constable in parts – especially in the trees. It was always on the aesthetic side that Webb failed … But his manner changes when he is working in imitation of Constable or Turner. He is endeavouring all the time to catch the trick of the brush, the breadth and sureness of handling, and consequently he is easily detected by the abject failure of the clouds and sky.

What is now clear is that L’Arc-en-Ciel was not so much ‘clever’ as inept, an amateurish copy rather than a skillful attempt to deceive. Its almost identical size and composition leads to the conclusion that it was painted in the presence of T12293.

The hypothesis that Edward Leader Williams purchased the Tate sketch, then, leads to one last, teasing possibility, namely that he, not Webb, was the painter of the L’Arc-en-Ciel. As Lord Windsor’s interview with B.W. Leader continued, Leader revealed how his father, an amateur artist, took delight in copying Constable:

My father, who amused himself with painting, copied an upright picture of a water-mill, and on Constable’s second visit to Worcester he took the copy away with him, saying he would work upon it. It was never returned, Constable dying shortly afterwards. My father I can recollect saying to me, ‘Mark my words, Ben, that copy will be sold for the original some day;’ and so it was! I saw it some years ago exhibited with a number of Constable’s works at the Grosvenor Gallery, having ‘John Constable, R.A.’ on the frame.54

Given his proclivities for copying Constable and the opportunity he may have had to copy the Tate sketch, it is entertaining to speculate that one of his forgeries has been in the Louvre for the past 134 years. Sadly, there are, to date, no authenticated works of Edward Leader Williams available for comparison. Perhaps that opportunity will some day present itself.