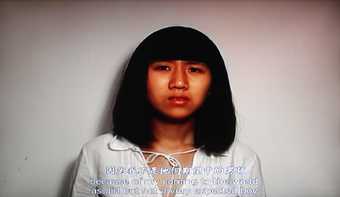

Chen Qiulin at Chen Qiulin: One Hundred Names at the Shepparton Art Museum, Australia (4 June – 24 July 2016)

Image courtesy of the artist and A Thousand Plateaus Art Space (Chengdu, PRC)

Photo: Chris Hawking

Monica Merlin: Let’s begin by talking about your early videos and the art you made between 2001 and 2002.

Chen Qiulin: I do not think it is a good thing when others call me an ‘artist’.

Monica Merlin: Why do you say that?

Chen Qiulin: I think that particularly in China, ‘art’ is something very chaotic. I think that while people are calling themselves ‘artist’, they do not necessarily have the sense of responsibility an artist should have. And also, what is ‘art’?

I was originally one of the Long March Space artists. Two or three years ago, I left them, because I felt that I could not do things that perfectly; that I was not an artist who could make perfect things. Also, I felt as if I was always on a road, but the road was getting harder and harder all the time – it was not all going smoothly for me as people imagined. I remember thinking that this was not the way things should be. Then, like you just said, from 2001 to 2002, I began to make art related to the Three Gorges. Actually, the Three Gorges Project has had a far-reaching influence on art in China and the things I made then are only a small part of it.

I have made films in that region for around twelve years now – continuously filming and always in the same area. That area, the Wanzhou district in the Sichuan Province, is my hometown, where I grew up. When I filmed there, I was not actually filming the Three Gorges Project, because I knew nothing about things like ‘hydroelectric construction’; I could not say one word about it. I think what I was doing was using the changes of one small place over time – including the changes in people and everything else surrounding them – to examine what exactly was going on in China at a time of rapid development. This is what I thought I was doing. But actually, many people would say that I was on quite a steady path; everyone said that what I was doing was good. Sometimes, I even felt that the amount of recognition I received was greater than the amount of things I actually did. They amplify the things you do, amplifying them up to a different level. This is all very good. I think it is great if a work of art can become a topic of conversation after its creation, or can inspire people to discuss issues in the way the Three Gorges Project did.

What is it that I find difficult at the moment? I feel that as I have created more work, I have realised what ‘art’ is. When I started off, it was merely out of passion. Back then, I thought that I understood art, because I had graduated from art school, read a lot of books and created a lot of paintings – I thought that I was an ‘artist’. But it is only after doing more work and spending a long time abroad that I realised, ‘Aha, this is what art is.’ It actually differs quite a lot from what you see with your eyes. In the last few years, I have continuously been thinking about turning myself upside down – actually, a better way to put it is that I have been thinking about what I want to do. This is really important: it is not about doing what is required by the gallery, or making things to fit in with the theme of an exhibition. So I think these past few years have been quite difficult for me.

In these past few years, I have been working with sculpture. In fact, I have constantly been trying to make a new path for myself. I chose sculpture because I wanted to stay in my studio to think things over. But I could not simply do nothing in my studio, so I did sculpture.

Chen Qiulin

Sitting 2008

Image courtesy of the artist and A Thousand Plateaus Art Space (Chengdu, PRC)

Chen Qiulin

My Thirty Years 2008

Image courtesy of the artist and A Thousand Plateaus Art Space (Chengdu, PRC)

Monica Merlin: In your sculptures, you have been using waste paper. What are your feelings towards waste paper as a material? There are many materials that you could have used, but you chose waste paper. Is there a particular reason for this?

Chen Qiulin: Yes. I think that used things possess a sense of time: they bear traces. Even if a used item is turned into something else, it still retains these traces. They are quite different from industrial materials.

Monica Merlin: True. Where does your paper come from?

Chen Qiulin: A lot of it is paper I have used myself, such as old newspapers and books I have read. When I first started making waste paper sculptures, it was just after the Sichuan earthquake. We all rushed over to take part in the rescue work, but actually we could not do anything – it was complete chaos. I then saw a lot of textbooks, test papers and so on in a ruined school. Without really thinking about it, I just picked these things up for the children. But after I had collected them, nobody came to pick them up. I did not know what to do. I did not even know if the children were…

Monica Merlin: That was a terrible time.

Chen Qiulin: Yes. At first, I made sculptures of myself, both as a child and as a grown-up. That is how I started making papier-mâché sculptures.

Monica Merlin: And how about your thoughts on the process of making with paper? I remember making things with papier-mâché when I was young. I thought it was a fascinating material – it starts off being wet and sticky, but becomes completely different when it dries.

Chen Qiulin: Yes and you just do not know what shape it will shrink into in the end. This could also be related to my block printing practice. I studied wood carving as my specialisation in art school. When you carve the wood, you might think that you have carved it in the way you imagined, but when it is printed you have no idea why it turns out the way it does! I really like the randomness: the unexpected things that develop during the process. But I can still control the overall situation.

Monica Merlin: So when you went to art school you studied wood carving. What themes were you exploring most often?

Chen Qiulin: I made a lot of carvings featuring public buses and bars, as they were the two places I loved going to most at the time! I really liked drinking, but I am a bit of a lightweight. In fact, I opened a bar as soon as I graduated from university.

Monica Merlin: In Chengdu?

Chen Qiulin: No, I went to university in Chongqing and I opened the bar in Wanzhou just after I graduated. But within two months, I drank myself out of business! I do not particularly like the taste of alcoholic drinks, but rather the atmosphere when you have lots of friends all drinking together. As I got drunk so easily, I would often get overexcited and tell everyone that they did not need to pay their bar tab! Two months later I was out of business.

Monica Merlin: You were too good to people!

Chen Qiulin: I really could not drink that much. I got dizzy in no time. A lot of people know this story. In China, I now work with A Thousand Plateaus Art Space. My boyfriend is the boss, but that is not the reason I work with them. Before we got together, we both agreed that our relationship and our work should be kept separate. He runs a gallery, which is very different from what I want to do. They do not pay me too much attention, so I feel very free. They do not force me to make things or to hold exhibitions, so I feel like I can work totally in accordance with my own ideas.

Monica Merlin: Have you only been dedicated to making papier-mâché sculptures in the last two years?

Chen Qiulin: Since I started making sculptures, I have completed two projects and also taken time to adjust my state of being. I want to find a new path, one that won’t necessarily be completely unrelated to what I was doing when I started. I feel that what I was doing initially was limited to a certain scope from start to finish. No matter what you film, other people will always say that it reflects the political environment. Just like I said before, what I actually want to work on is the changes occurring in China. I am not in Beijing very much. Even though I have had a studio there, the longest I have ever stayed is fifteen days. After that I just cannot stand it anymore, because in China, cities like Beijing, Shanghai and Chengdu are huge metropolises, which are just the same as many other huge metropolises around the world. They cannot represent the true China.

The true China is made up of small places that most people have never even heard the name of. Change is happening in these places just as fast as it is in Beijing. And although the changes in these places may be small, they are truly terrifying. This is what I want to work on. It is the same with the films I made in Wanzhou. At the outset, I filmed things because I felt nostalgic. But later on, after two or three years, I would be shocked at the changes that had taken place. It is really terrifying. And these changes are happening in every single city in the world; they all are changing. So what I would like to do now is to find a way to bring these things to a broader platform that can reflect China’s changes in a wider perspective and not just the changes brought by the Three Gorges Project.

Another topic that I am working on has to do with the individual. More and more I feel that the relationship between the individual and the collective is one of both conflict and coalescence. In China, this is especially strange.

Back to the paper sculptures. I have done two projects since I started making the paper sculptures last year. In both, I explore a new direction. In one project, while I made seven groups of figures, the work is actually about talking to myself about what I want to do. This piece is called Possibility. It is basically a work in which I entered into a dialogue with myself. The second project was The Empty City. This is a video installation made up of seven screens. But I still feel like neither of these projects realised was what I truly wanted.

Monica Merlin: Why?

Chen Qiulin: I want to find what it is that I want. But when I was doing these two projects, I felt like I had gone backwards. Everyone has their own habits when they do things; while you are doing something, you might find that you are still falling into the same old habits instead of moving forward. When I was doing these two projects I felt that I had not managed to leave these habits behind. But this year I was starting to work on my plans and I feel like I was able to break out of my old habits. So I am very happy this year – over the last few years, I had been feeling quite depressed.

Monica Merlin: I would like to ask you about women artists in the contemporary Chinese art world – I now know you do not like the term ‘artist’ though!

Chen Qiulin: It is fine! I said I do not like the word because too many people use the word far too readily, especially people who are not experts.

Monica Merlin: How are things for women artists in Chinese contemporary art and society? Do you think that women artists have the same opportunities as male artists, in terms of exhibiting their works? Do you think people truly understand the art created by women artists?

Chen Qiulin: It is hard to say – there are a lot of layers to this question. It is something you could do some research on. If you ask me, my answer would be that there are no differences between male and female artists. But I definitely would not tell women artists who have not yet had many opportunities that there is equality; I have a lot more opportunities than they have. Now nobody would ask me to hold an exhibition because I am a woman, or say to me that my work is great because I am a woman. But this can be an opportunity for a lot of women artists who are not so famous. In China right now, there are many women artists who pop up at all kinds of opening ceremonies to promote themselves to various curators. But I think men probably need to do this too.

Monica Merlin: Do you mean that when you started making video you were already successful?

Chen Qiulin: Not at all. I know that when I first started, people only invited me to exhibitions because I was a woman. If I were a man, I might not have had those opportunities. Chinese women artists whom you know have all attained a certain level of fame, at least in their respective fields. But many female artists are working at quite a different level. Their work is also very hard to talk about. For example, when you and I talk about artworks, the conversation might get very specialised. Sometimes when I am talking with women artists – quite a few from Chengdu – I found that I just could not communicate with them.

Monica Merlin: Do you think it is because they approach art from a different perspective from you?

Chen Qiulin: If someone, male or female, is working hard solely for the purpose of getting opportunities, their work will not be any good. I also think that they look at art and other things in a very narrow way.

Monica Merlin: I saw that in another interview, you said that some people think you are a man when they see your work. What do you think about statements like this?

Chen Qiulin: It does not bother me. I like being a woman! But if people say I am a man I am not bothered. Sometimes I feel like I have no gender.

Monica Merlin: Do you have anything you want to say about feminisation, or your experience as a woman when growing up and living in the society?

Chen Qiulin: Do you mean my upbringing as a woman? If so, you have asked the wrong person! When I was young my parents were very busy with their work. My parents’ generation had it really tough and there was nobody to keep an eye on me. I grew up just like that, not like the kids today who have lots of people to look after them. When I was young I was very…

Monica Merlin: Independent?

Chen Qiulin: Yes. I had a shaved head until my second year of primary school, because my mother thought that brushing my hair was too much trouble.

Monica Merlin: How did you feel about that?

Chen Qiulin: When I was young I was very shy. The girls would not let me into the girl’s toilet and the boys would not let me into the boy’s toilet. That was a real pain! But everything else was fine, I think.

Monica Merlin: And after that? When you were a bit older?

Chen Qiulin: Later, I pretended to be lonely. I pretended that I loved reading poetry and books I could not understand – I really did not understand them! My father studied literature and his books were the ones I read the most. All my grades were poor apart from Chinese, which I did OK in.

Monica Merlin: How did your parents react when you decided to go to art school?

Chen Qiulin: They were not very happy. My father thought that it would better to knuckle down and study hard in university, get a job in a government department and live peacefully for the rest of my life. This was the life they wanted their children to have. They never imagined they would have a daughter like me who would give them such a headache!

When I was a bit older, but still in primary school, I finally knew that I was a girl. My scores were not good and so the teachers did not like me. In any case, I do not have much of an impression of those years – I just muddled through and grew up.

I played with the boys all through high school, because we all had bad grades! It was great though. Now we are still good friends, but everyone thinks it is strange that I would end up taking such an odd path and eventually end up becoming a person of culture!

My life is the one I chose, unlike many of my generation whose lives were determined by their parents. When I was applying to go to art school, my parents locked me up at home. I packed a bag and got ready to sneak out. Then my mother locked me in my room again and put my bag somewhere else. They did not want me take the entrance exam. Later, I got a friend to come and break the lock. I ran off, leaving my bag at home. By the time my mother found out, I was already in Chongqing and she could not do anything about it and so she brought the bag over for me.

Monica Merlin: Did they support you and the choice you made later on?

Chen Qiulin: At that time, I was being disobedient. It is different now. Now, my mother knows that this is my job. They would not have supported me at the time. They just thought I was terribly disobedient!

Monica Merlin: But now you have participated in international exhibitions and people from China and around the world have interviewed you about your videos and art. Your parents must be happy.

Chen Qiulin: They are very happy now. They even say to other parents, ‘Let your children grow up by themselves and do not mind them. Look at our daughter, she turned out OK!’ But at the time, they wanted to beat me to death. I was often beaten for being naughty, because I always made them angry. They would often get phone calls from the school teacher asking them to come in. I knew I was in big trouble then!

From a young age, I did not like the rules in the school. There were rules telling you what to do, what scores to get and what texts to memorise. I thought being able to read is all you need. Why do you have to memorize things? Chinese education is very strange, but we cannot do anything about it.

Monica Merlin: Did you yourself perform in your videos, for example in Farewell Poem?

Chen Qiulin: I appear in many videos, but there are also many in which I do not. I think most of the time I managed to show my face.

Monica Merlin: Did you study performance or dance? Or did you study it at home?

Chen Qiulin: I learned to dance when I was young with a teacher in my hometown.

Monica Merlin: Do you have a favourite work that you would like to talk about?

Chen Qiulin: Not really…

Monica Merlin: Then could you choose a work that you think is particularly important in your artistic career and discuss it briefly? If you do not want to choose one, I will.

Chen Qiulin: Great. You choose. I really do not know what to choose.

Monica Merlin: Since I have not seen some of your most recent works, such as the seven-screen video you mentioned earlier, could you tell me more about the processes behind that work – how it was made and what the result was?

Chen Qiulin: That video series, Empty City, features today’s Wanzhou. The text is a part of this work, an extra part. I have only exhibited this work once in New York. They put it on seven big screens and the overall effect was quite good. It is due to be shown at my solo exhibition at the Honolulu Museum of Art in Hawaii in March 2014 and this time I said that I wanted my text to be displayed in the gallery too. The idea behind this work is as follows. My childhood home has changed so much that it is now completely unfamiliar to me, so I wanted to look at it from several different angles. The city is filled with objects and it is quite big, but my memories of the place have all gone. I started filming in a park. When we were young we did not have many places to play other than the park, something every city has. Back then I thought that this park was a really big and happy place, but now it is desolate, decrepit and small. It is surrounded by tall buildings and the park area is really tiny. I started filming from there and went on to film the schools that I attended.

Monica Merlin: So all the places you filmed have a special significance in your own life story?

Chen Qiulin: Yes, most of them. I also put on a facial mask and my father’s military uniform. People think that wearing the military uniform is a political statement, but it is not. For me, I chose it because my father said he could protect me when I was young: that gave me a feeling of great security. When I got older, I still remember that safe feeling and my father’s clothes also made me feel warm inside. That is why I brought them along. Then people ask why I wore a mask and speculate around it. But actually it is because when people see my videos they comment on my performance – I wanted to cover myself up. I wanted to completely efface the individual.

Monica Merlin: What happens when you walk out of the park?

Chen Qiulin: The text I wrote is related to my memories of the things in the video. There are people dancing in the park. You might not be aware of this, but there was a major incident in China last year. It is tied up with politics and it is pretty complicated. There was an official called Bo Xilai in charge of Chongqing and when he was in charge there he would get people to dance in the parks. The people were all very happy to do so. We filmed a sequence related to this. Then I was chased by the police! Because I was wearing a military uniform, had a facial mask on and was holding a string of balloons!

Monica Merlin: What did they think?

Chen Qiulin: They thought I was completely mad!

Monica Merlin: What did they say to you?

Chen Qiulin: Nothing! I ran off straight away, but the camera operator had all the equipment and could not run anywhere. All the equipment was confiscated, but before the police took it away, the camera operator cleverly took the tapes out and put them in his bag.

Monica Merlin: Is this episode in your video?

Chen Qiulin: No, we could not film it. They started encircling us slowly from far away. I realised that something was wrong and ran off, shouting at everyone else to run too. When I looked back, the camera operator had been pinned down. But as soon as I had shouted out for everyone to run, he took the tapes out.

Monica Merlin: So do all the seven screens of this work show different places that hold memories for you, like the park and schools?

Chen Qiulin: Yes, everything is related to my memories. One scene shows the only old alleyway in Wan County that had not been demolished. I used a long take, over ten minutes, to film the people still living in the alley as they passed though the shot. I filmed their lives and the way the area is now.

Monica Merlin: Thank you. I look forward to seeing it.

Monica Merlin interviewed Chen Qiulin at the 798 Café, Beijing on 25 November 2013.