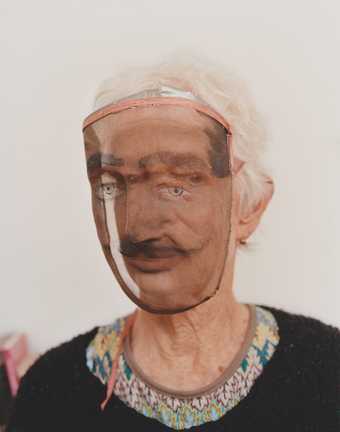

Exhibit A

André Breton's 'slipper spoon', photographed by Man Ray, 1934

© Man Ray Trust/ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2018

It is a quiet day in 1934. Two men are wandering the crammed stalls at the Puces de Saint-Ouen flea market in Paris, looking around, but in an unfocused way. One of them notices an odd-looking metal mask among the bric-a-brac and buys it. Soon after, the other is drawn to a long, rounded, wooden ladle. At the base of its handle is carved a clunky shoe shape. The phrase ‘le cendrier de Cendrillon’ (‘Cinderella’s ash tray’) has been going around the man’s head for days, and the ladle seems to respond to something in him. The mask would go on to provide the inspiration for the face of Alberto Giacometti’s sculpture The Invisible Object 1934, while the ‘slipper spoon’ found by André Breton would provide the basis for what he would call ‘dream objects’. Breton, as one of the founders of surrealism, saw ‘found’ things and everyday stuff as central to their movement: by recombining and presenting them in unexpected ways, they could give access to the desires and urges of our subconscious. Breton enthusiastically described their flea-market jaunt in his 1937 book Mad Love, and his ‘slipper spoon’ marked an acknowledgement of the innate power of things, a viewing of objects as possessing an inner essence. His imagining of the potency of objects seems a combination of several ideas around at the time. The found object had already made its way into European art, from Picasso’s use of scraps of newspaper in his collages in 1912 to Duchamp’s first exhibited readymade, Bicycle Wheel 1913, demonstrating that art could be made from stuff on the street or at home. Picasso had also been drawn to the objects that had been accumulating at ethnographic museums in France and Germany since the 1870s: masks, totems and carvings from different cultures, brought back from colonial endeavours across Africa. While Modigliani, Picasso and others were inspired by these African objects, drawing on their perspectives of the human body, they treated them much as the museums did: they kept them entirely divorced from the context of their creation or use, and without consideration of whatever forces might dwell inside. Those Europeans who did attempt to understand these African cultures, and the objects they produced, were introduced to the notion of animism: that anything – a rock, a tree, a stream or a sculpture – has its own spirit and is, in a sense, alive. It seems the concept of animism, combined with Sigmund Freud’s popularised ideas on the subconscious, coalesced into the surrealist understanding of the object, and how it could be wrenched from the sitting room and allowed to show its own power. That power was, for the surrealists, more like a mirror, however – one that could reflect the hidden, interior mind of the person who chose that object. Writing in a 1937 issue of the magazine Country Life, British artist Paul Nash described the surrealist take on found objects as ‘probable and poetic’, qualifying this with ‘but I foresee difficulties in its practical application’. For him, objects held their own inscrutability, an essence that had to be treated with mutual respect. Having discovered objects that he felt possessed their own presence – such as a found piece of gnarled wood that he felt compelled to refer to as the ‘Marsh Personage’ – Nash became preoccupied with ‘the life of the inanimate object’: ‘The more the object is studied from the point of view of its animation, the more incalculable it becomes in its variations.’ While this resulted in artworks that were physical assemblages, as well as painted representations of combinations of objects, Nash’s attitude is one of a more direct animism, where the object isn’t a reflection of the artist, but might be placed in a position to speak for itself, as it were. What both Nash and Breton illustrate, though, are early 20th-century European precursors to the way objects are currently being deployed and displayed in contemporary artists’ work.

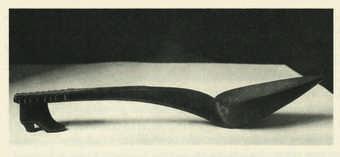

Exhibit B

Installation view of Mark Leckey's BigBoxStatueAction, sound systems 'in conversation' with Henry Moore's Upright Motive No.9 1979, Serpentine Gallery, London, 2011

Courtesy the artist and Cabinet, London. Photo: Mark Blower

A two-metre-high set of homemade speakers are blasting forth a sound collage of rumbling bass notes, high choral voices and the occasional ‘wop-bop-a-loo-bop-a-lop-bam-boom’ excerpted from Little Richard’s 1955 hit ‘Tutti Frutti’. A voice promises, ‘I’m going to persuade you’, though of what the listener will be persuaded is never specified. The sonic assault echoes throughout Tate Britain’s Duveen galleries. A crowd is gathered there, but the focus of this wave of sound isn’t human: it’s the large, awkward, alabaster sculpture facing the speakers – Jacob Epstein’s Jacob and the Angel 1940–1.

Mark Leckey’s performance BigBoxStatueAction 2003 was an attempt, as he put it, to ‘try and coax a response out of this strange, mute monstrosity’ – to perhaps converse with it by appealing to the monumental sculpture in a way that it might understand or respond to: vibration. His performance has since been repeated with his attempt to ‘talk’ to a Henry Moore sculpture in the Serpentine Gallery in 2011. On neither occasion did the statues seem to reply – but perhaps we just didn’t know how to listen, or what to look for.

The imminent agency of things is a central concern in Leckey’s work, and he seems constantly to be devising ways to try and commune with them. His touring exhibition The Universal Addressability of Dumb Things 2013 placed a vast range of objects – from history to pop culture – in close proximity, including William Blake’s death mask, which was wired up to an EEG machine next to a Cyberman helmet (from Dr Who); all, again, to see what cross-object communication might take place.

Leckey’s practice is indicative of a widespread approach among current artists that attempts to recognise the mysteriousness of objects, and locate a new animism in the stuff we find all around us, whatever that might be. Amalia Pica’s yearlong project I am Tower of Hamlets, as I am in Tower of Hamlets, just like a lot of other people are 2011–12 saw a small, pink, granite sculpture of an Echevaria plant passed around to over 50 different homes in east London, each keeping it and using it as they liked for a week. The project was an experiment in what sort of exchanges might take place between the different hosts and roaming guest: what memories did it accrue, or disclosures did it make? All we can know is found in several photographs documenting its position in some of the houses: sat in a garden, on a dresser, or used as a poppadom holder on a dinner table.

In 1929 the English mathematician and philosopher Alfred North Whitehead defined the object as a ‘vacuous actuality’: a hollow thing entirely defined by the context around it, and its relations to other things. Much art of recent decades ascribes to this view – in particular, those artworks labelled ‘institutional critiques’, which attempt to call attention to the mechanisms of viewing art, or those that draw on anthropological methods to examine the impossibility of objectivity. While this new animism might appear outwardly to draw on ethnographic and museological methods in presenting us with objects to consider, what it’s asking us to reflect on is the inverse. In this regard, one line from artist Joseph Kosuth’s 1974 text ‘(Notes) on an Anthropologized Art’ stands out: ‘particular to art is the capacity to “speak” (in the sense of saying the unsayable) in a vacuum’. Perhaps it is in the vacuum space of art, where objects might be partially uprooted from their contexts and unstuck in time, that we might glimpse the essence of the things in themselves. Here we might also come to understand what curator Dan Cox called ‘thingly time’, and, at least, give objects some space where they can decide to do so themselves.

This current animism takes a range of forms. In the collages and installations of Cypriot artist Haris Epaminonda, she places images of African sculptures, and at times the objects themselves, in careful arrangements that give no clues as to when or where these things might appear from, asking us to look closer and imagine another timeline for them. British artist Simon Fujiwara, for the show History is Now 2015 at the Hayward Gallery, set out a series of plinths, each with a distinct artefact on top: in some cases, artworks, such as one of Damien Hirst’s spot paintings or Sam Taylor-Johnson’s David 2004 (a video of David Beckham sleeping), or a large lump of coal. Fujiwara’s things might be familiar to us now, but his arrangement suggests a museum for non-human visitors.

For Lebanese artist Haig Aivazian’s project Rome is not in Rome 2016, he replicated parts of ancient Roman artefacts, presenting them as a pseudo-archeological site within a ruined palace in Marrakech. More recently, in 1440 Sunsets Per 24 Hours 2017, he placed inordinately bright stadium lights in a small gallery space in Paris, lining the floor with the octagonal metal poles that usually support them.

Such arrangements place us in different, sometimes intimate or awkward, proximity to the textures and tones of things. With this new animism, these artists ask us to reassess our relationships with objects, to see and appreciate them in ways we haven’t yet conceived. If we properly pay attention, what will they do?

Chris Fite-Wassilak is a writer and critic who lives and works in London. His short book of essays Ha-Ha Crystal is published by Copy Press.