Members of the Total Design group

Any standard art or design history book will offer a pretty convincing portrait of László Moholy-Nagy as twentieth -entury Renaissance Man, perpetually fluent and outspoken at the vanguard of painting, photography, graphic design and typography, and amply supported by his own theoretical writing. Moholy-Nagy's key influence, however, was as a teacher: his convictions were consistent, his rhetoric prophetic, his purpose moral, social and all-inclusive. He was a disseminator, out to spread the word rather than envelop it in avant-garde elitism, believing equally in the necessary heroism of the capital-M Modernist and necessary humility of the lower-case-p pedagogue.

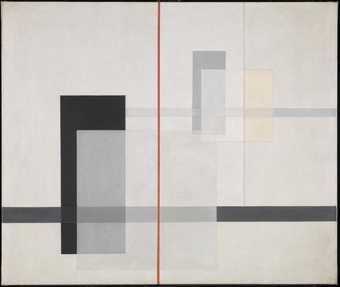

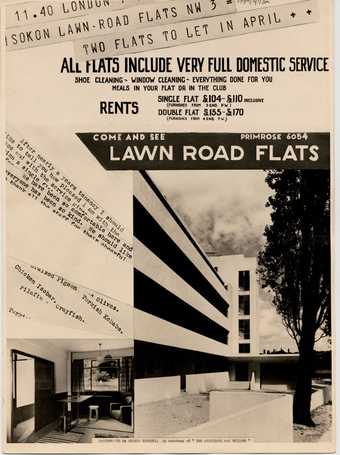

A Bauhaus teacher from the age of 27, Moholy-Nagy worked closely with Walter Gropius to establish a publishing wing of the Bauhaus. At the end of his own contribution, Painting, Photography, Film, the chapter "Dynamic of the Metropolis" combines all three: a painterly experimental film script collaged from photography and expressive typography. This work single-handedly itemises all the components of the Bauhaus graphic design legacy: active use of asymmetry and space to enhance meaning; thick De Stijl-style rules; elements compartmentalised and offset at brutal angles; repetition towards graphic clamour; heavy contrast between typefaces, geometric devices and colour. Although now the clichés of graphic Modernism, in "Dynamic" these elements were not merely stylistic, but focused on how to convey effectively the moving image through static print. They were translating from film to paper by integrating typography and photography (his own typical compound coining was "typofoto") in a manner wholly appropriate to the kind of revolutionary documentary film at that time.

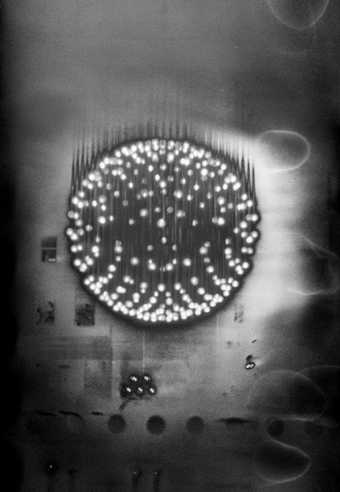

After five years at the Bauhaus, Moholy-Nagy put this wealth of theory into freelance practice across Europe during a nine-year break from teaching. His work from this period – such as his London Underground posters – combined all elements of the classic Bauhaus foundation course (line, texture, tone, composition, etc) and drew equally from collage, painting, film and photography to create space and movement, while his commercial book jackets and advertisements followed the same obsessions as his private photography of friends, objects and locations. Media, life and work perpetually bled into and infected each other.

One of his great legacies was his last book Vision in Motion, published posthumously in 1947. It is primarily divided into sections – Problem, Analysis and Method – with each chapter itemised and abbreviated, listing the form and content of his life with the same economy and rhetoric of his graphic work. In the introduction he describes using quotations to replace images "so text becomes illustration". Such lateral thinking is the essence of Moholy-Nagy's graphic design – the constant sliding back and forward between text and image, between editing and designing. All his key books are illustrated with as much of his students' and colleagues' work as his own, and this is only one passing indication of the extent to which his teaching and practice were intertwined, and how they informed one other.

One such student project included in Vision in Motion was the "tactile chart in bent plastic" made by his most renowned protégé Robert Brownjohn. Brownjohn's later work in New York and London throughout the 1950s and 1960s remained profoundly marked by Moholy-Nagy's face-to-face influence, an inheritance that included the ability to distil beauty from the ordinary, the conviction of simple, precise composition and, most of all, the reputation as a charismatic multi-talent. Brownjohn took Moholy-Nagy's intellectual rigour and applied it to the burgeoning pop culture, infusing it with smart humour to create the visual jokes of so-called idea-based design, subsequently picked up and repeated to death by Pentagrams everywhere.

The more serious-minded Constructivist strand of Moholy-Nagy's legacy was pursued by fellow émigrés such as Herbert Bayer and Ladislav Sutnar in the United States, equally fluent and progressive in both advertising and information design. The synthesis of disciplines was continued by the likes of Saul Bass, whose work in film extended from posters to title sequences and cameo direction, all bearing his trademark succinct minimalism, and then a generation later by Tibor Kalman, whose plurality of style and clientele ranged from clocks to restaurant interiors and the whole gamut of graphic design in between. In Amsterdam, Wim Crouwel's Total Design was perhaps the most extreme of the integrated studios, its projected image virtually a parody of corporate professionalism. While, in California, the expansive play of Charles and Ray Eames across the arts marked the most complete marriage of life and work.

Moholy-Nagy emphasised his understanding of Gesamtkunstwerk as being essentially distinct from Gesamtwerk. Gesamtkunstwerk is usually translated as a "total work of art", generally meaning multi-disciplinary, which, although integrated, is still qualified and as such considered alongside life. His reading of Gesamtwerk – literally "entire work" – however, asserts an all-encompassing life-work compound. Moholy-Nagy's legacy was to avoid the narrowing of experience through single-minded professionalism and careerism by encouraging the mastery of all techniques towards uninhibited plurality and imagination. Most importantly, he taught people to think – that designing is a euphemism for thinking, and that "man, not the product, is the end in view".