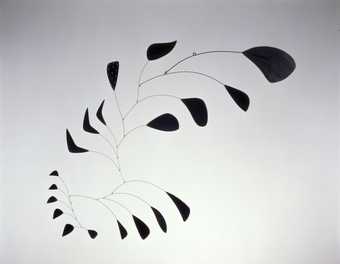

Calder travelled to Paris in the 1920s, having originally trained as an engineer, and by 1931 he had invented the mobile, a term coined by Duchamp to describe Calder’s sculptures which moved of their own accord.

His dynamic works brought to life the avant-garde’s fascination with movement, and brought sculpture into the fourth dimension.

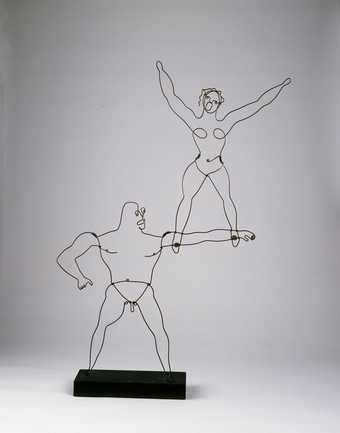

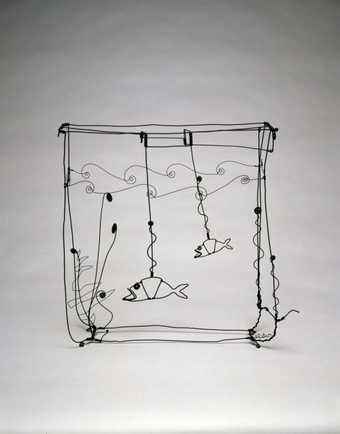

Continuing Tate Modern’s acclaimed reassessments of key figures in modernism, Alexander Calder: Performing Sculpture will reveal how motion, performance and theatricality underpinned his practice. It will bring together major works from museums around the world, as well as showcasing his collaborative projects in the fields of film, theatre, music and dance.

Watch a short film on Calder

Calder’s work created a sensation in the 1930s, he took sculpture and liberated it, and set it in motion.

Dara Ó Briain

In this short film, comedian and Theoretical Physics graduate Dara Ó Briain talks about his love of the cosmos and its connection with Alexander Calder’s mobiles: