Henry Moore OM, CH Relief No.1 1959

Image 1 of 15

-

Henry Moore OM, CH, Relief No.1 1959© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Relief No.1 1959© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Relief No.1 1959© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Relief No.1 1959© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Relief No.1 1959© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Relief No.1 1959© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Relief No.1 1959© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Relief No.1 1959© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Relief No.1 1959© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Relief No.1 1959© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Relief No.1 1959© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Relief No.1 1959© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Relief No.1 1959© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Relief No.1 1959© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Relief No.1 1959© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Relief No.1 1959© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Relief No.1 1959© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Relief No.1 1959© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Relief No.1 1959© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Relief No.1 1959© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Relief No.1 1959© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Relief No.1 1959© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Relief No.1 1959© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Relief No.1 1959© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Relief No.1 1959© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Relief No.1 1959© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Relief No.1 1959© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Relief No.1 1959© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Relief No.1 1959© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Relief No.1 1959© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH,

Relief No.1

1959

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

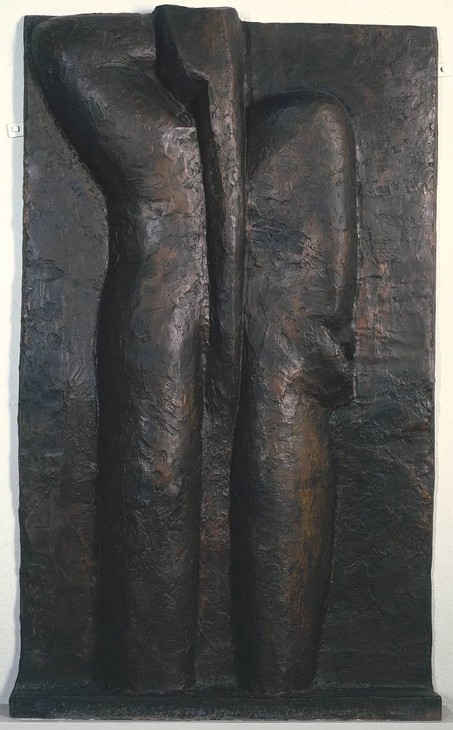

Relief No.1 1959 is a rare example of a free-standing relief sculpture in Moore’s work. The front surface comprises an undulating arrangement of shapes that suggest the schematic form of a female figure, which appears to be embedded within or emerging from the flat ground. Moore’s interest in relief sculpture in the late 1950s developed from architectural commissions and a trip to Pompeii, where he saw casts of corpses half buried in volcanic ash.

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Relief No.1

1959

Bronze on a bronze base

2219 x 1251 x 498 mm

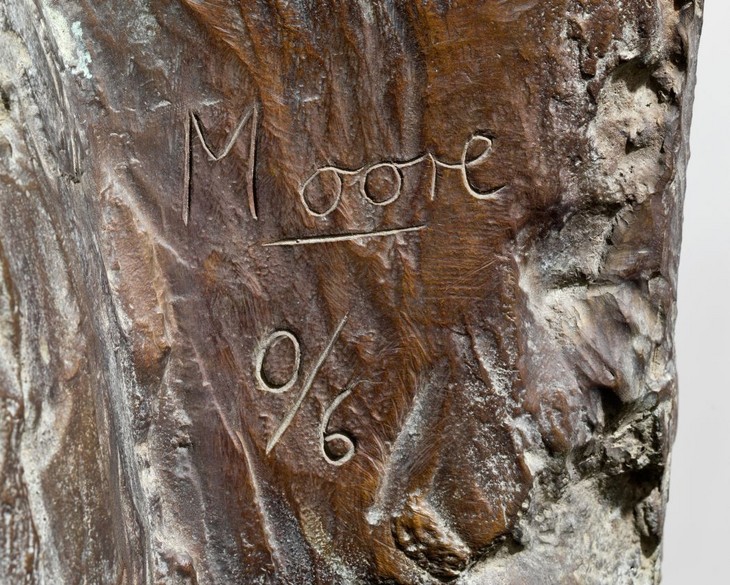

Inscribed ‘Moore 0/6’ and ‘H.NOACK BERLIN’

Presented by the artist 1978

Artist’s copy aside from edition of 6

T02284

Relief No.1

1959

Bronze on a bronze base

2219 x 1251 x 498 mm

Inscribed ‘Moore 0/6’ and ‘H.NOACK BERLIN’

Presented by the artist 1978

Artist’s copy aside from edition of 6

T02284

Ownership history

Presented by the artist to Tate in 1978 as part of the Henry Moore Gift.

Exhibition history

1960–1

Henry Moore: An Exhibition of Sculpture from 1950–1960, Whitechapel Gallery, London, November–January 1961 (?another cast exhibited no.71).

1968

Henry Moore, Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller, Otterlo, May–June 1968; Museum Boymans-Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, September–November 1968, no.100.

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery, London, June–August 1978, no number.

References

1960

Will Grohmann, The Art of Henry Moore, London 1960, p.232 (original plaster reproduced pl.190).

1960

Henry Moore: An Exhibition of Sculpture from 1950–1960, exhibition catalogue, Whitechapel Gallery, London 1960, reproduced no.71.

1965

Herbert Read, Henry Moore: A Study of his Life and Work, London 1965, p.224 (?another cast reproduced pl.210).

1965

Alan Bowness (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 3: Sculpture and Drawings 1955–64, 1965, revised edn, London 1986, no.450 (?another cast reproduced pls.72–3).

1966

Philip James (ed.), Henry Moore on Sculpture, London 1966, pp.275–7 (?another cast reproduced pl.126).

1968

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller, Otterlo 1968 (another cast reproduced).

1968

John Hedgecoe (ed.), Henry Moore, London 1968, p.391 (?another cast reproduced p.391).

1968

John Russell, Henry Moore, London 1968, p.178 (?another cast reproduced pl.183).

1973

Henry J. Seldis, Henry Moore in America, New York 1973 (another cast reproduced p.183).

1977

David Finn, Henry Moore: Sculpture and Environment, New York 1977, pp.87–9, 490.

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1978, reproduced p.40.

1979

Alan G. Wilkinson, The Moore Collection in the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto.

1979

1979, p.161 (original plaster reproduced pl.138).

1981

[Richard Calvocoressi], ‘T.2284, Relief No.1’, The Tate Gallery 1978–80: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions, London 1981, p.127.

1987

Alan G. Wilkinson, Henry Moore Remembered: The Collection at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto, Toronto 1987, pp.186–7 (original plaster reproduced no.138).

2006

Deborah Emont-Scott, ‘Relief No.1’, in David Mitchinson (ed.), Celebrating Moore: Works from the Collection of the Henry Moore Foundation, London 2006, pp.259–61 (another cast reproduced no.187).

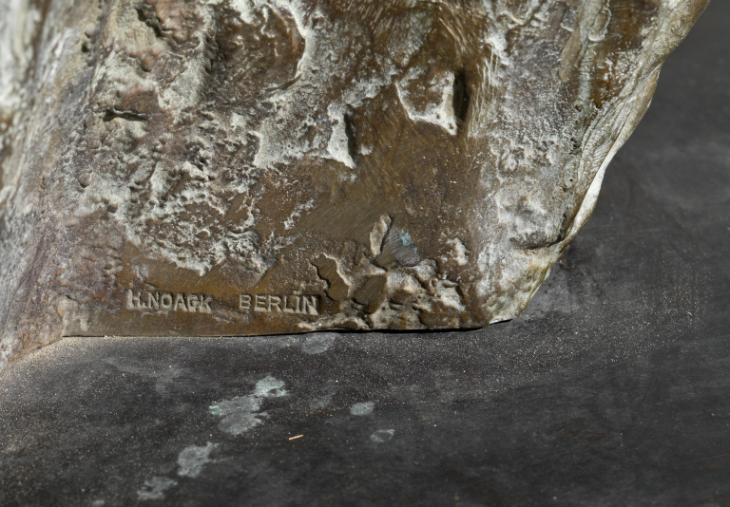

Technique and condition

This large relief sculpture was cast in bronze from an original plaster model, which would have been made by applying successive layers of plaster to a supportive armature. The surface texture of the bronze bears evidence of this process, demonstrating how Moore built up the wet plaster with a spatula. Further traces of Moore’s working process can be seen in the chisel marks and striations on the surface, which would have been made once the plaster had hardened (fig.1). A mould was then taken from the finished plaster so that the sculpture could be cast in bronze. This bronze was cast at the Noack Foundry, West Berlin, in an edition of six plus one artist’s copy.

Henry Moore

Relief No.1 1959 (rear view)

Tate T02284

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Henry Moore

Relief No.1 1959 (rear view)

Tate T02284

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of patina on Relief No.1 1959

Tate T02284

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Detail of patina on Relief No.1 1959

Tate T02284

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

As this sculpture is a relief, numerous marks providing valuable insights into the casting process remain visible on its rear side. For instance, the weld seams have not been filed down on this side and show that the sculpture was cast in four large sections that were welded together (fig.2). Residues of dark sand can also be seen, indicating that the bronze was made using the sand casting technique, which involves burying a model in sand to create a mould from which the bronze can be cast. This technique is quicker and less labour intensive than lost wax casting but is generally less suitable for reproducing very intricate shapes or surface details. Since the bronze has to be cast in a single pour, the maximum size of any one piece of bronze is dependent on the crucible size that the foundry uses. This means that it is often more practical and carries less risk to fabricate larger bronzes from a number of parts. The raised crackle pattern on the rear surface shows where the molten bronze ran into cracks in the mould. All evidence of faults and welds would have been removed from the front of the relief by means of a process known as ‘chasing’. This would have required such areas to be abraded and textured with punch tools to integrate them with the surrounding surface. Aside from being cleaned and chemically patinated, the bronze has received no further modifications and retains the surface details of Moore’s original plaster.

The patination process involved applying chemical solutions to the bronze that reacted with the metal to produce coloured compounds. A rich dark brown colour was applied to this sculpture, overlaid with a light green that has been rubbed back on the high points (fig.3). This type of finish imitates the colour that a bronze would acquire naturally if displayed outdoors. After patination the surface of the sculpture was waxed to protect it.

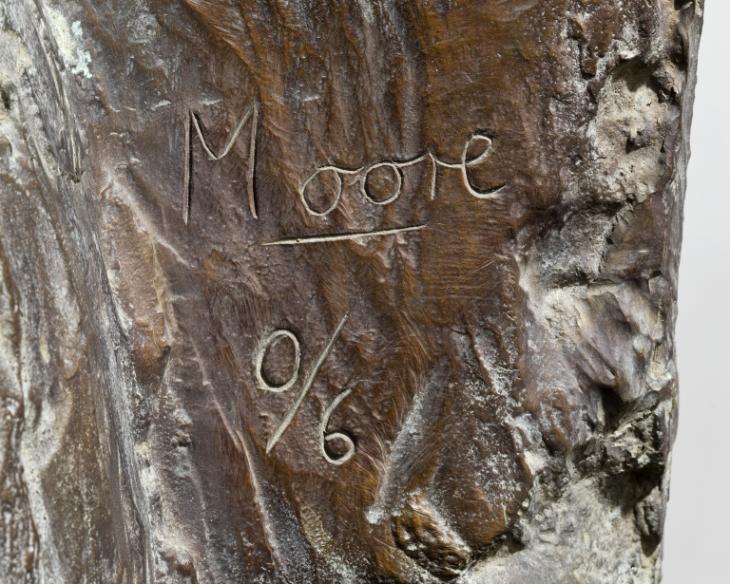

Detail of artist's signature and edition number on Relief No.1 1959

Tate T02284

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Detail of artist's signature and edition number on Relief No.1 1959

Tate T02284

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

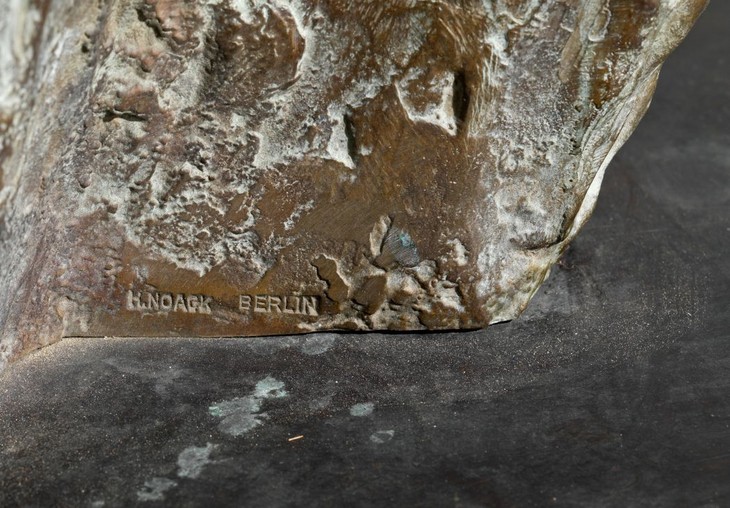

Detail of foundry mark on Relief No.1 1959

Tate T02284

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.5

Detail of foundry mark on Relief No.1 1959

Tate T02284

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Relief No.1 is fixed to a flat, rectangular bronze base by threaded bolts. These bolts pass from the underside of the base through flanges welded at the bottom of the rear side of the sculpture. The artist’s signature and edition number have been inscribed towards the lower right-hand side of the sculpture (fig.4). The foundry mark ‘H.NOACK BERLIN’ has been stamped between the signature and the sculpture’s lower edge (fig.5).

Lyndsey Morgan

March 2013

How to cite

Lyndsey Morgan, 'Technique and Condition', March 2013, in Alice Correia, ‘Relief No.1 1959 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, April 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://wwwEntry

Relief No.1 1959 is a tall bronze relief sculpture, which when seen from the front comprises a relatively flat rear plane capped with a triangular point, from which various rounded and angular forms project. As a whole, the configuration of these forms loosely outlines the shape of a standing human figure divided into three distinct sections: the head and shoulders at the top, the central abdomen, and two legs cut off at the knees at the bottom. Sharp recessions between these sections interrupt the continuous evocation of a body in space, although the fact that the figure appears to lean to one side, with its right leg projecting further than the left, gives the impression that it is stepping forward. The depth of the sculptural relief identifies it as a mezzo relief, for around half of the volume of the figure projects from the surface. Unlike most relief sculptures, which are designed to be integrated into walls and only be seen from one side, Relief No.1 is a free-standing sculpture.

Detail of head and shoulders of figure in Relief No.1 1959

Tate T02284

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

Detail of head and shoulders of figure in Relief No.1 1959

Tate T02284

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of abdomen of figure in Relief No.1 1959

Tate T02284

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Detail of abdomen of figure in Relief No.1 1959

Tate T02284

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The neck and head of the figure are denoted by a vertical, semi-cylindrical shaft with a domed top, which tapers down into a rounded, almost horizontal shelf representing the shoulders (fig.1). When seen from the front the shoulders slope slightly upwards from left to right, where a rounded swelling may outline the top of an upper arm. Below the shoulders, occupying the position of the abdomen, is a more angular protrusion made up of sharper, irregular shaped surfaces and a thin disc-like appendage that juts out from the surface at a right angle (fig.2).

Detail of legs of figure in Relief No.1 1959

Tate T02284

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Detail of legs of figure in Relief No.1 1959

Tate T02284

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of arch between legs of figure in Relief No. 1 1959

Tate T02284

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Detail of arch between legs of figure in Relief No. 1 1959

Tate T02284

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Although the hips and legs of the figure are not anatomically accurate, they are the most recognisably human features of the sculpture and take the form of rounded swellings that lead down to thick semi-cylindrical thighs, which terminate abruptly at the base (fig.3). The two legs are separated by a wide, arched recessed space, the depth of which is accentuated by a series of parallel lines that fan outwards from the cavity (fig.4).

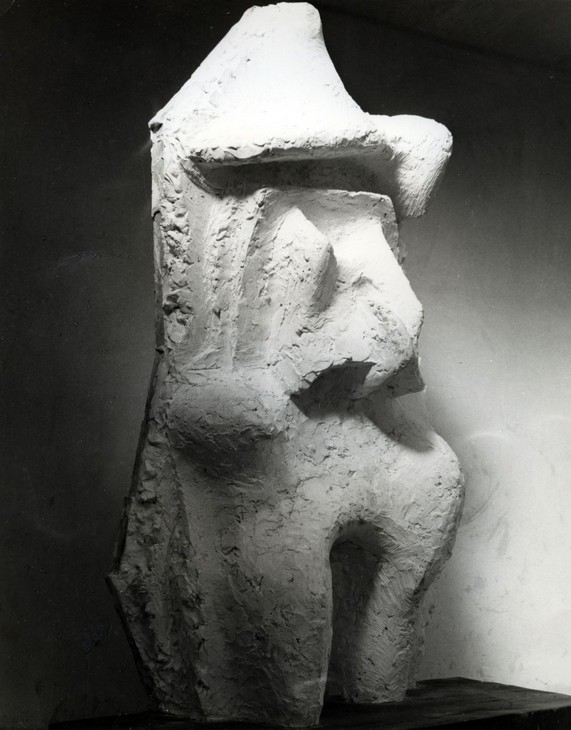

From clay to plaster to bronze

By 1959, when Relief No.1 was created, Moore had moved away from making preparatory drawings for his sculptures and had started making small three-dimensional models in clay, plaster and other malleable materials. It is likely that Moore made the plaster Maquette for Relief No.1 (fig.5) in the maquette studio on the grounds of his home, Hoglands, at Perry Green in Hertfordshire. This studio was lined with shelves displaying Moore’s ever growing collection of found bones, shells and flint stones, the shapes of which often served as starting points for Moore’s formal experiments in three dimensions. In 1963 he described how he worked with these objects to the critic David Sylvester:

I look at them, handle them, see them from all round, and I may press them into clay and pour plaster into that clay and get a start as a bit of plaster, which is a reproduction of the object. And then add to it, change it. In that sort of way something turns out in the end that you could never have thought of the day before.1

The shapes of the projecting forms suggest that Moore may have created Maquette for Relief No.1 by first pushing natural objects into a piece of clay, which was then cast in plaster.

Henry Moore

Relief No.1 1959

Plaster

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.6

Henry Moore

Relief No.1 1959

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of newspaper print on plaster Relief No.1 1959

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Alice Correia

Fig.7

Detail of newspaper print on plaster Relief No.1 1959

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Alice Correia

Once Moore was satisfied with the design of his maquette it was scaled up to a full-size plaster version (fig.6). The enlargement process was probably carried out in the White Studio at Hoglands by Moore’s studio assistants, who in 1959 included Geoffrey Harris and Phillip King. He was able to allocate the bulk of the enlargement work to others because, as curator Julie Summers has noted, it was ‘a scientific rather than artistic process’.2 Using the small maquettte as a guide, an armature was constructed from wood or chicken wire over which successive layers of plaster were built up. According to James Copper, Sculpture Conservator at The Henry Moore Foundation, it is likely that this plaster sculpture was created lying flat on the ground before being lifted into its vertical position.3 A piece of newspaper attached to the rear of the sculpture is dated 16 April 1959, and may indicate when work on the plaster enlargement commenced (fig.7). Once the full-size plaster version was near completion Moore would have taken over to texture the surface. A second standing relief was made in plaster around the same time, but this was not cast in bronze because Moore was not sufficiently pleased with the arrangement of the forms.4

When the plaster version was complete it was sent to the Noack Foundry in West Berlin to be cast in bronze. By the late 1950s Noack was regarded as one of the best bronze foundries able to undertake large-scale castings. To cast this sculpture the plaster had to be cut up into four pieces and covered in sealants and resins so that moulds could be made into which molten bronze could be poured. Seams where the four pieces of bronze were subsequently welded together are clearly visible on the rear of the sculpture (fig.8). On the front they were filed down and smoothed using a technique known as ‘chasing’.

Detail of patina on Relief No.1 1959

Tate T02284

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.9

Detail of patina on Relief No.1 1959

Tate T02284

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

After it had been cast at the foundry the bronze sculpture was returned to Moore so that he could inspect the casting and make decisions about its patination. A patina is the surface colour of a sculpture and is usually achieved by applying chemical solutions to the bronze surface. The inner areas and edges of Relief No.1 have a dark brown patina while the high points – those projecting furthest from the rear surface – are a lighter golden brown. A reddish tinge can be seen on certain areas of the surface, while a mottled green patina appears in the crevasses and recesses (fig.9). When the sculpture entered the Tate collection the gallery’s conservators Derek Pullen and Jackie Heuman determined that the patina of this sculpture should not be exposed to the elements, and so it has only ever been exhibited indoors.

Sources and development

Moore rarely made relief sculptures because he usually preferred to sculpt in the round. According to former Tate curator Richard Calvocoressi:

his [Moore’s] interest in making relief sculpture, which had lain dormant since his work on the London Underground Building in the late Twenties, was reawakened when he was commissioned to design a large wall relief in brick for the façade of the Bouwcentrum in Rotterdam, unveiled in December 1955. This project led to the idea of releasing the forms from their incorporation in the fabric of the wall so that they become free-standing.6

Henry Moore

Wall Relief: Maquette No.3 1955

Bronze

333 x 48 x 484 mm

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.10

Henry Moore

Wall Relief: Maquette No.3 1955

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

his [Moore’s] intention in Relief No.1 had been to emphasise the projectional, forceful qualities of relief as opposed to using it pictorially like a narrative frieze, as Renaissance sculptors had done and as he had been taught to do at art college. Hence the stylisation and exaggeration of certain protrusions and recessions in the sculpture: the umbilicus and the chest, for example.8

The ‘forceful qualities’ that Moore wished to convey in Relief No.1 were recognised in critical responses to the sculpture. In 1968 the art critic John Russell asserted that ‘in the monumental Relief No.1 the human body is seen as something robust as a rhino: with something, in fact of a rhino’s armoured hide, and something of its power to trample and thrust when and where we least expect it’.9

Plaster cast corpse at Pompeii 1954

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore

Fig.11

Plaster cast corpse at Pompeii 1954

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore

Henry Moore

Reclining Figure 1956–60

Elm

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.12

Henry Moore

Reclining Figure 1956–60

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Along with the Rotterdam commission, Moore’s renewed interest in relief sculpture may have originated from his trip to the archaeological site of Pompeii, Italy, in 1954. There he observed the effects of the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79, which buried the Roman town in volcanic ash. He was particularly intrigued by the plaster casts of preserved corpses lying on the ground, which he photographed from various angles (fig.11). Although discussions of Moore’s visit to Pompeii are usually restricted to interpretations of his sculpture Falling Warrior 1956–7 (Tate T02278), his photographs of embedded and fragmented bodies may also have influenced the figurative forms of Relief No.1 and his other major relief sculpture from the period, Reclining Figure 1956–60 (fig.12). In this large elm sculpture the figure adopts the pose of a reclining figure, but is orientated vertically so that it appears to be standing with bent knees against a flat wall, from which she appears to have emerged. Although this figure has been carved in high relief, and possesses more recognisably human features, the orientation of the figure and the way in which it protrudes out of the rear plane bears a resemblance to Relief No.1.

Another possible influence on Moore’s development of Relief No.1 may have been Henri Matisse’s series of Backs, which Tate acquired in the mid-1950s (Tate T00081–T00082, T00114, T00160; see fig.13). These four sculptures progressively reduce the form of a standing female nude to essential shapes, and represent Matisse’s attempt to ‘consider the nude as an arrangement of forms that he could simplify and stylise’.10 The four sculptures were purchased individually by Tate between 1955 and 1957 and were known to Moore, who while serving as a Tate trustee in May 1956 was asked by the director Norman Reid to advise how they should be displayed.11

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Figure 1931

Beech

object: 248 x 178 x 121 mm

Tate T00240

Purchased 1959

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.14

Henry Moore OM, CH

Figure 1931

Tate T00240

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

In 1965 the critic Herbert Read suggested that ‘the torso has been modified into a sinister mask’, whereby the middle and lower sections of the sculpture may be read as the long, gaunt face of an elderly man (fig.15).13 According to this interpretation the shoulders double as a furrowed brow above eyes formed by the rounded bulges at the top of the central protrusion, while the projecting disk can be seen to form a large nose with pronounced nostrils. The left hip can then be understood as a cheekbone, and the legs as swollen cheeks surrounding an open mouth.

In his assessment of the sculpture Russell concluded that ‘old-style aestheticizing, and considerations of “beauty” and “ugliness” are meaningless in the context of this relief. It is, understandably, one of the least popular of his pieces: and nothing could give more conclusive proof of Moore’s vitality as an artist then his ability to produce a commandingly powerful work which almost nobody likes’.14

The Henry Moore Gift

Relief No.1 was presented by Henry Moore to the Tate Gallery in 1978 as part of the Henry Moore Gift. The Gift comprised thirty-six sculptures in bronze, marble and plaster and was exhibited in its entirety alongside Tate’s existing collection of Moore’s work in an exhibition celebrating the artist’s eightieth birthday, which opened in June 1978. A press release was duly prepared announcing that ‘The group [of sculptures] is the most substantial gift of works ever given to the Tate by an artist during his lifetime’.15 Relief No.1 was included in the birthday exhibition, which was attended by over 20,500 people and nearly 11,000 copies of the catalogue were sold.16 At its close in late August the Director of Tate, Norman Reid, reflected in a letter to Moore’s daughter Mary Danowski that although he was sad to see the exhibition come to an end ‘we have the consolation of the splendid group of sculptures which Henry has presented to the nation’.17

Relief No.1 was cast in bronze in an edition of six plus one artist’s copy, which now belongs to Tate. Other casts are held in the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto; Israel Museum, Jerusalem; Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebaek; the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City; and the Henry Moore Foundation, Perry Green. The plaster original is also held in the collection of the Henry Moore Foundation.

Alice Correia

April 2013

Notes

Henry Moore cited in David Sylvester, ‘Henry Moore Talking to David Sylvester’, 7 June 1963, transcript of Third Programme, BBC Radio, broadcast 14 July 1963, p.18, Tate Archive TGA 200816. (An edited version of this interview was published in the Listener, 29 August 1963, pp.305–7.)

Julie Summers, ‘Fragment of Maquette for King and Queen’, in Claude Allemand-Cosneau, Manfred Fath and David Mitchinson (eds.), Henry Moore From the Inside Out: Plasters, Carvings and Drawings, Munich 1996, p.126.

Moore compared Relief No.2 with Relief No.1 in a conversation with the photographer John Hedgecoe in 1968: ‘Of these two I only cast one into bronze because I was dissatisfied with the other. The plaster one [Relief No.2] has not yet satisfied me. The projecting parts are too evenly spread and too evenly apportioned throughout the figure. There is no obvious focal point. In the bronze sculpture you know the middle and you know where the shoulders are. It has a centre, a kernel, and an organic logic.’ See John Hedgecoe (ed.), Henry Moore, London 1968, p.391.

[Richard Calvocoressi], ‘T.2281, Three Motives Against Wall No.2’, The Tate Gallery 1978–80: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions, London 1981, p.126.

Alan G. Wilkinson, Henry Moore Remembered: The Collection at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto, Toronto 1987, p.187.

[Richard Calvocoressi], ‘T.2284, Relief No.1’, The Tate Gallery 1978–80: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions, London 1981, p.127.

‘Henri Matisse, Back IV 1930, cast 1955–6’, display caption, Tate, http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/matisse-back-iv-t00082/text-display-caption , accessed 12 April 2013.

Norman Reid, letter to Henry Moore, 23 May 1956, Tate Public Records TG 1/6/36. Moore is known to have admired Matisse’s sculptural work. See John and Vera Russell, ‘Moore Explains His Universal Shapes’, New York Times Magazine, 11 November 1962, reprinted in Alan Wilkinson (ed.), Henry Moore: Writings and Conversations, Aldershot 2002, p.123.

Related essays

- Scale at Any Size: Henry Moore and Scaling Up Rachel Wells

- Henry Moore: The Plasters Anita Feldman

- At the Heart of the Establishment: Henry Moore as Trustee Julia Kelly

- Henry Moore's Approach to Bronze Lyndsey Morgan and Rozemarijn van der Molen

Related catalogue entries

Related material

How to cite

Alice Correia, ‘Relief No.1 1959 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, April 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www