Introduction

In 1628, Edward Norgate, a musician and courtier to Charles I, included a short discussion of pastel painting towards the end of Miniatura, or the Art of Limning, the popular book on miniature painting on which he had worked for some years. As the first account in English of what Norgate described as ‘Dry Colours’ or ‘Crayon when it speakes French’, his four-page description introduced England to a medium that was to gain a remarkable sway over popular taste. Pastel, as it later became known, arguably became one of the defining characteristics of British portraiture in the following century, yet it has largely been relegated to the sidelines of 18th-century art’s accepted narrative. This display and accompanying essay aims to reinstate the medium to its rightful place in the art-historical story of the period by examining its gradual rise and subsequent fall from grace.

While Norgate may take credit for first bringing pastel to the attention of England’s artists, his pioneering account appears to have been almost unintentional. He was drawing his observations on watercolour to a close, when he suddenly doubled back: ‘[I] have bethought mee of another Species of painting’ he continues ‘the study and practice whereof, is […] necessary, usefull, easy and delightfull.’ Describing the pastel work he had seen in Paris, Haarlem and Rome, he advocated the use of fabricated ‘Proper Colours’ which ‘may passe for Painting’ as opposed to the natural black, white and red chalk which was in widespread use for preparatory drawing. His brief explanation ends with a dispatch at once both encouraging and dismissive:

Thus they do at Rome and I verily beleeve…you may make as good at London, and soe much for Crayons.1

The medium took some time to become accepted in England; Edward Luttrell, author of the second English treatise regarding pastel, written 35 years later, was still referring to ‘Crayons’ as ‘of a Newer date and not so Common as the other painting’. 2 Yet Norgate’s assessment of pastel as ‘necessary, usefull, easy and delightfull’ was perceptive. It established the key factors in its eventual, phenomenal success, building from around 1680, when it truly began to flourish as a medium in its own right, to its gradual demise around 1800 (albeit with periodic revivals thereafter, most notably by the Pre-Raphaelites and Impressionists).

The word ‘phenomenal’ is used intentionally. In the early 18th century, knowledge of the correct use of the pastel medium was still relatively rare in an English context. However, the return of young men from their grand tours in the 1710s, bearing souvenir pastel portraits by Rosalba Carriera and other continental artists, established an English market for this type of portraiture. Subsequently, the arrival of the artists Arthur Pond and George Knapton in London, in 1727 and 1732 respectively, and their vigorous promotion of the medium, learnt in Italy, further fuelled enthusiasm for pastel among London’s fashionable art-buyers. Their shrewd marketing cut through the ferment of quasi-alchemical secrecy that surrounded the art. Many tales regarding this, most probably highly embroidered, still circulate. For example the artist John Greenhill, who was allegedly forced to discover his master Sir Peter Lely’s undisclosed pastel technique by spying on him as he drew a portrait of his wife. By 1741, the writer George Vertue noted pastel’s considerable popularity in London, remarking that:

Crayon painting has met with so much encouragement of late years here […] and the painters finding it much easier in the execution than Oil colours, readily came into it.3

Thirty years later, its appeal had not waned. In the early 1770s, the popular young Irish pastellist Hugh Douglas Hamilton was besieged with business at his Pall Mall portrait studio, ‘scarcely [able to] execute all the orders that came in upon him’ and reduced to throwing payment among the ‘bran and broken crayons’ that littered the floor.4 Though this anecdote may well be a colourful invention by Hamilton’s 19th-century biographer (a number of surviving bills and receipts indicate that Hamilton probably wasn’t paid in this manner), it indicates the market that existed for such work and the almost relentless pace of production required to meet demand. The artist’s harried schedule often frustrated customers such as the collector Horace Walpole, and Hamilton later attributed his troublesome ‘attacks of the nerves’ to it. At the close of the same decade, the Bath townhouse of the arbiter of taste and fashion, Beau Nash, was decorated ‘with the beauties of the age, painted in crayons, chiefly by the ingenious Mr Hoare [pastellist William Hoare]’, while John Russell, the most successful of all 18th-century British pastellists was able to command similar prices to the President of the Royal Academy, Joshua Reynolds, at the peak of his popularity in the 1780s.5

It is arguably as a consequence of this success, however, that pastel remains a marginal, if now emerging, subject of interest. Pastel was often the subject of critical censure by the 18th-century art world’s great and good, and derided as an inconsequential distraction from the artist’s true purpose of oil painting; ‘much commended for novelty’ in George Vertue’s words, but ‘not much esteemed’ in those of his contemporary André Rouquet, reporting on the ‘present state of the arts in England’ in 1755.6

Leading British painters such as Joshua Reynolds and Benjamin West were prominent in the chorus of disapproval. Reynolds dismissed the work of the fashionable Swiss pastellist Jean-Etienne Liotard, who worked in London for several years in the 1750s, as ‘just what ladies do when they paint for their own amusement’, reminding his students that the paintbrush ‘is the instrument by which he must hope to obtain eminence’.7 Equally, correspondence between Benjamin West and the young American artist John Singleton Copley, who was contemplating a move to England in the 1760s, finds West urging Copley to abandon pastel and concentrate solely on his oil-painting. Somewhat surprised, Copley in turn requested West to ‘be more explicit on the article of Crayons and why you dis[ap]prove the use of them, for I think my best portraits done in that way’.8

The volume of pastels produced across Europe in the 18th century may have much to do with the low esteem in which the medium was, and to some degree continues to be, held. Yet the number of pastels – in particular pastel portraits – executed in these years suggests that as a means of artistic expression they accorded incomparably well with the particular conduct of 18th-century life. As Edward Norgate suggested; they were ‘necessary’ as a cheaper, portable, quickly-executed alternative to portraiture in oil; they were ‘usefull’ in reflecting new, less ceremonious forms of sociability; they were ‘easy’ enough to be attempted by thousands of amateur artists; and ‘delightfull’ in their unparalleled ability to record contemporary fashions. As a fledgling medium, with few set rules, pastel was uniquely placed to respond to an evolving social context and track customers’ changing desires. With no direct precedent before the 17th century, technique was not cut and dried and pastel artists were free to innovate, constantly developing new ways to exploit the medium’s very particular qualities.

Natural chalk

The distinction made by Edward Norton between fabricated ‘Proper Colours’ and naturally occurring black, white and red chalk is an important one in the pastel story. Though a small number of manufactured tints have been found in the work of Hans Holbein (1497/8–1543) and a handful of Italian artists, including Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) in the late 15th and early 16th centuries, their use was limited and intermittent at this early stage. Most artists still relied on natural chalk, made from a few types of coloured earth – carbon, haematite and calcium carbonate or soapstone – which they employed solely for preparatory drawings and sketches. The 17th-century work by an unknown artist, A man at a window with a child and another figure (fig.1) in the Tate collection, is typical of the kind of quick, observational drawing in natural chalk then considered essential to the development and practice of any artist.

British School 17th century

A Man at a Window; a Child; Another Figure

Tate

Likewise, the unfinished drawing Head of a man in profile, attributed to Nathaniel Dance (fig.2), and John Jackson’s sensitive portrait of David Wilkie (fig.3) both suggest moments seized; an informal request to capture a likeness, perhaps during a social visit. Jackson and Wilkie had met as students at the Royal Academy Schools around 1805. Jackson’s well-observed, lively red chalk drawing – worked in a network of fine lines and capturing the movement of the sitter’s hair with particular skill – dates from around a decade later and was one of a number that Jackson executed of his artistic contemporaries, including John Flaxman, Sir Francis Chantrey and James Northcote.

Attributed to Sir Nathaniel Dance-Holland

Head of a Man in Profile to Left

Tate

John Jackson

Sir David Wilkie, R.A.

(c.1815–20)

Tate

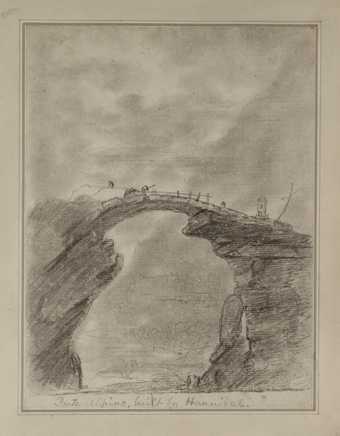

Natural chalks were also considered particularly useful for landscape sketching due to their ease of portability, as witnessed by the series of studies made by Richard Wilson on display. Ponte Alpino (fig.4) depicts a picturesque bridge in the small Veneto town, 80 kilometres north of Venice. It is typical of the many landscape sketches, both topological and imaginary, that Wilson made while in Italy from 1750 until 1756, and after his return to England. Wilson’s Italian sojourn was instrumental in his decision to commit to the landscape genre, having previously practised as a portraitist, and these drawings show the artist embracing his new direction with zeal.

Richard Wilson

Ponte Alpino Built by Hannibal

Tate

Landscape sketching was an equally important preoccupation for John Constable. He sketched the countryside around him ceaselessly from an early age and, above all his artistic contemporaries, was keenly dedicated to the cause of naturalism. However, the Tate’s loose, impressionistic Wooded Landscape with Church Tower, (fig.5) executed in black and white chalk on blue paper, is, unusually, either a copy of a Gainsborough drawing or more probably – as a Gainsborough original has yet to be found – an exercise in Gainsborough’s style. Constable was a life-long admirer of the older artist and is known to have owned a number of his drawings.

John Constable

Wooded Landscape with a Church Tower

Tate

Natural chalk drawing was also promoted as part of formal artistic training, with students encouraged to make chalk copies of prints, paintings and casts of well-known classical sculptures in order to learn about anatomy. The Figure Study by J.M.W. Turner, (fig.6) included in this display, was probably the result of his early studies in the plaster academy at the Royal Academy Schools, where he enrolled in 1789.

Equally, in the life of a busy artist’s studio, where many artists gained their training through apprenticeship, copying allowed pupils to gain technical skills and the art of capturing a likeness, while keeping them out of the way of paying sitters. The drawing of an Unknown Man c.1751–7, (fig.7) attributed to the prolific draughtsman Joseph Wright of Derby, is thought to be a studio drawing executed while Wright was a pupil of the portrait painter Thomas Hudson. While with Hudson, Wright made numerous compositional poses and drapery studies after the work of van Dyck, Sir Godfrey Kneller and Jonathan Richardson. Unknown Man is probably a copy made after a print or painting by Sir Peter Lely, using natural red and white chalk. The antiquarian style of the drawing signals its 17th-century derivation, while the variety of lines and marks employed demonstrates Wright’s considerable skill.

Attributed to Joseph Wright of Derby

Study of an Unknown Man

(c.1751–7)

Tate

Giles Hussey

Head of a Saint

Tate

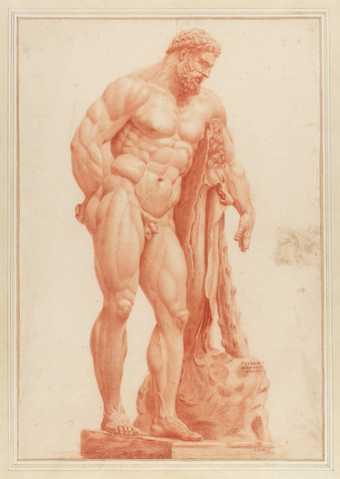

Giles Hussey’s Head of a Saint (fig.8) was probably executed while he was in Rome in the early 1730s as a pupil of the painter, sculptor and engraver Ercole Lelli. Under Lelli’s guidance, Hussey developed the spare, delicate style, for which he later became known, by copying antique sculpture and Renaissance painting. Likewise, Richard Dalton’s large, highly-finished red chalk drawing The Farnese Hercules of 1742, (fig.9) dates from the period during which he studied under the artist Agostino Masucci, also in Rome, and is one of a series after classical statues. With its complex web of layered cross-hatching, it demonstrates how refined and sophisticated academic chalk techniques had become.

Richard Dalton

The Farnese Hercules

(1742)

Tate

The full palette

Natural chalks continued to be used for both sketching and, on occasion, finished works, well into the 18th century, but a number of artists simultaneously became interested in extending the scope and use of so called ‘dry colour’. The portrait painter Sir Peter Lely (1618–1680) is the first British artist known to have used fabricated chalk. From the 1650s, his prized ‘craion’ likenesses – produced independently from his oil portraits and executed mainly in black and red natural chalk – were increasingly enhanced with passages of pink, blue, white and yellow pastel on the sitters’ faces. In 1662, the Dutch scientist Christiaan Huygens (1629–1695), who was fascinated by the new medium, records visiting Lely’s studio with his brother. After considerable persuasion, Lely allowed Huygens to accompany him to his pastel supplier, where he purchased 54 coloured crayons.

While most early English pastel practitioners would have made their own colours, pre-prepared pastels were also increasingly available, as Lely and Huygens’s excursion suggests. Given the many complications entailed in balancing the ingredients, this development was instrumental in the medium’s rise to popularity. By the 1730s, pastels could be readily purchased in London and most major European cities in a wide range of colours and half-tones. Prospective pastellists went to great lengths to secure the best examples, with the finest said to come from Bernard Stoupan of Lausanne in Switzerland. The connoisseur Horace Walpole’s correspondent Horace Mann wrote from Florence in 1747 that he had a commission to send Walpole’s cousin (probably Mary Walpole) who had recently ‘turned painter’, ‘a load of pastelli […] which I can luckily send in the greatest perfection from hence’. They duly arrived in a special box ‘contrived by a very eminent painter in crayons with the proper divisions, and the quantity of each sort he tells me is sufficient for a long time’.9

Another crucial element in pastel’s success was the entrepreneurial figure of Arthur Pond; dealer, framer, painter, engraver, pastellist and above all keen businessman. He shrewdly marketed pastel portraits, which were relatively inexpensive, to female consumers who could afford to purchase them with their pin-money (the money given to them by their husbands for personal expenses). Pond’s extensive receipt books, now at the British Library, reveal that of his 88 female patrons more than two-thirds bought pastel-portraits, roughly twice the percentage of men. Pond also gave lessons in the art to a number of aristocratic female amateurs, including Grace, Countess Dysart. Other leaders of fashion such as Lady Burlington, Lady Dorothy Saville and Lady Beauclerk were guided by artists such as William Kent and George Knapton. While the end results were often of variable quality – Horace Walpole reported that Lady Lucan ‘painted in crayons, and as ill as any fine lady in England’ – there is no doubt that their interest in the medium contributed positively to its burgeoning popularity around mid-century.10

In response to increasing demand, London began to fill up with pastel artists. In the 1740s George Vertue noted that ‘inferior Crayoneer painters of portraits, as young Pine [Robert Pine] &c […] brush them off at a guinea apiece to begin [and] in this manner great Numbers are done’.11 The lack of expensive, cumbersome equipment required to execute work in pastel – a drawing board and a box of crayons were all that was strictly necessary – attracted many young artists. Hugh Douglas Hamilton and his fellow pastellists from the Dublin Schools, such as Thomas Hickey and Alexander Pope, were an exceptionally itinerant group; chasing a larger client pool and opportunities for greater income in London, Paris and Rome. As Hamilton’s frequent changes of studio in London further indicate (he moved premises five times between 1765 and 1775) pastellists were uniquely placed to chase potential clients – the fashionable elite – and present themselves for service wherever required.

Pastel operated in an art world that ran parallel to that of Joshua Reynolds and the Royal Academy; intersecting only at the time of the annual exhibitions, when even then it generally languished beneath the critical radar. This was an art world led by popular consumer taste rather than academic decree. In this context, pastel’s popularity among amateurs gave it a clear advantage, for it had created a market of knowledgeable customers, with direct experience of the art and an intimate understanding and appreciation of the skill involved. Potential patrons had the language in which to discuss these works, culled straight from the proliferation of instructional manuals which they had studied for their own practice. The remarkably uniform vocabulary that sprang up around pastel, due to the rampant piracy and copying of large chunks of text from one manual to another, undoubtedly aided such appreciation. Those who commissioned pastel portraits could talk readily and knowledgeably about ‘sweetening’, ‘cooling crayons’ and ‘pearly teints’. Equally, the close viewing conditions prescribed for works in pastel (leading practioner Francis Cotes advised that they were best suited to ‘apartments that are not too large’) and their easily legible surfaces allowed the kind of aesthetically sensitive viewer who emerged in the 18th century the gratification of appreciating stylistic distinctions and the pleasure of informed admiration.12

The display of a virtuoso range of ‘styles’ arguably became a self-conscious preoccupation of many pastellists, not least John Russell whose confident handling enabled him to employ a dazzling array of diverse techniques. The two examples in the Tate collection – Boy and Cat and The Fortune Teller – are a wonderful demonstration of the possibilities of the medium. Boy and Cat (fig.10) is typical of Russell’s popular, sentimental ‘fancy pictures’ (genre works, rather than named portraits), though in this instance the sitter is known. He is Morton William Lawrence (1787– c.1841), who later became a sugar refiner in Whitechapel, London, depicted at around the age of two or three. Different treatments have been used on every part of this work; from the painterly, curlicues of wet pastel used to depict the lacy edging of the boy’s dress to the feathery strokes of his hair; from the broken, staccato lines of unblended pigment which conjure the cat’s fur to the velvety darkness of the clouds in the sky beyond. The Fortune Teller (fig.11) is another ‘fancy picture’, which may have been exhibited contemporarily as Artifice and Credulity. Like Boy and Cat it revels in the coy depiction of youth contrasted directly with gnarled age in the figure of the white-haired seer. The blue paper and deep blue ground Russell habitually employed in combination with his vibrant palette – evident in the fortune teller’s sash – gave his work a lasting freshness and brilliance.

John Russell

Boy and Cat

(1791)

Tate

John Russell

The Fortune-Teller

(exhibited 1790)

Tate

These works represent only two of Russell’s huge output in pastel, estimated at around 1,250 works. He was unquestionably the most successful pastellist of the period, with a solidly middle-class clientele – doctors, lawyers and merchants – who had gradually replaced the aristocracy who first favoured the medium.

While the aesthetic variety and visual sophistication of the best pastel portraits was a significant draw for patrons, they also held a more prosaic appeal; reflecting the unprecedented desire for material possessions and enthusiastic spending which came to characterise mid-18th century fashionable life. The variety of textural effects which could be achieved with the medium, depending on its formulation and application, made it particularly suited to the representation of textiles and the detail of fine clothing. Though Joshua Reynolds once again expressed his disapproval – ‘It is the inferior stile that marks the variety of stuffs’ – for many patrons the way in which pastel functioned as a veritable inventory of fashionable attire formed a large part of its appeal.13 Pastel, understood to be an ephemeral medium due to its delicate surface, seemed a perfect fit for the equally fleeting vagaries of modish taste. Indeed, in recognition of pastel’s unparalleled capacity to translate this fascination with fashion into pictorial record, John Russell dedicated a whole section of his widely-circulated and influential Elements of Painting with Crayons, first published in 1772, to the topic of clothing.

The facility with which the pastellist Ozias Humphrey could render the detail of a sitters’s apparel in a portrait such as Baron Nagell’s Running Footman, is a case in point. In a display of contrasting textures, the footman’s elaborate dress is carefully observed; from the smooth planes of his bright blue and red tunic to the voluminous ruffle of his shirt. His towering headpiece, consisting of a red cap wound with a band of white silk, dominates the portrait; its exuberant feathers barely contained by the picture frame. The Dutch Ambassador Baron Nagell was well known for his flamboyantly dressed servants and evidently delighted in their exotic appearance; a pride that may have led to the commissioning of this portrait. A contemporary reference to Nagell’s first court appearance in London in March 1788 noted that ‘he makes a splendid appearance with his footmen in scarlet and silver and a gay page or Running footman was vastly well Received’.14

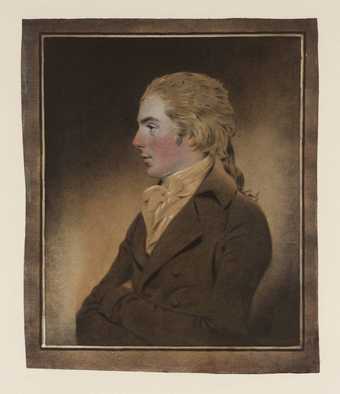

Competition

As consumer enthusiasm for pastel grew, the market became increasingly saturated. Around 1780, there were said to be 2,500 artists working in the pastel medium in Paris, while newspaper advertisements reveal that around the same time in London, many pastellists were forced to sell their services from tavern to tavern. The most innovative among them concocted novel techniques with which to draw jaded clients. One of the most successful of these was the ‘reverse pastel’ method practised by John Downman, in which he applied pastel to the reverse of translucent Indian or Chinese paper, which was then laid down onto a thicker sheet. The soft, airy effect achieved was closer to a mezzotint print than a traditional pastel and proved extremely popular. Two fine examples of Downman’s work in the Tate collection, Lady Clarges and Mr Currie, (figs.12, 13) show this technique in action.

John Downman

Lady Clarges

(1790)

Tate

John Downman

Mr Currie. Half Length, in Profile to Left

Tate

Similarly, the portraitist Daniel Gardner, who mixed pastel, gouache and oil paint in a unique manner, had a keen eye on the competition. His highly original techniques included the use of pastel, scraped to dust and applied, with the aid of a liquid medium, in layers of transparent pigment. The young Irish artist John Warren noted the success of Gardner’s innovations, citing him as the reason for Hugh Douglas Hamilton’s return to his native city, Dublin, in 1776. In a letter to his mentor Andrew Caldwell, Warren remarked:

I hear Hamilton is gone to Ireland, pray how does he go on? I dare say he will meet with much encouragement. Strange that a man with so little comparative Merit as Gardiner shd beat him out of the field which nevertheless is as I am told literally the case.15

Gardner’s large-scale group portrait The Family of Archbishop Moore c.1780 depicts the wife and children of Archbishop John Moore and is a good example of the artist’s unusual methods and bold experimentation. Adopting a decorative approximation of the grand style (more commonly seen in the oil paintings of his former teacher Joshua Reynolds), complete with swag curtain, pillars and full-length figures, the application of colour is nonetheless loose and flowing. Mrs Moore’s dress is a riot of unblended strokes and the trees in the distance are rendered with scratchy loops of dry pastel. The portrait showcases a typical Gardner palette, dominated by cool blues and pinks with flashes of red and orange. While this work was executed largely in pure pastel – unusual for the artist – he has made use of gouache throughout and shiny gum arabic in the trunks of the trees to the right.

The decline of pastel

Though both Gardner and Russell boasted a loyal clientele, it was undeniable that pastel’s moment had passed. Gardner retired at the height of his fame, around 1800, and while Russell’s remarkable success continued until his death in 1806, it represented the final flourish of an art that by the 1790s appeared distinctly old-fashioned. In 1796, Joseph Farington recorded that at a Royal Academy committee meeting:

A letter was read from Sir James Wright stating that ‘having observed how much Crayon painting is fallen off in what he sees at the Exhibitions’. He offers the Academy a portrait by F. Cotes of Bromfield, the surgeon, as a lesson to the Students.16

Writing in the same year, the critic Anthony Pasquin dismissed pastel as ‘chiefly calculated for the observance of those, whose love of softness and finery govern their applause and protection’.17 Once appreciated for its informality and intimacy, capturing a sensual, sociable age of luxury and refinement, it seemed almost inevitable that pastel would fall from favour as the austere purpose and idealisation of Neoclassicism, and its associated politics, ascended. The political mood in both England and France had indeed become fatally inhospitable to the medium. The use of pen and ink and the promotion of a linear drawing style had long been politically charged for radical artists such as James Barry, who advocated its purity and truthful simplicity in preference to illusionistic subtleties of tone and texture. By the 1790s, and thanks in large part to the widespread popularity of the artist John Flaxman’s outline drawings, the moral underpinning of this aesthetic preference was a given. In such thinking, elegantly articulated by the contemporary philosopher Immanuel Kant in his Critique of the Power of Judgement of 1790, colour and texture were seen to be superfluous, even deceptive. They were understood to mask the truth of essential forms, or what the collector, amateur artist and writer George Cumberland preferred to call ‘the inestimable value of chaste outline’.18

Perhaps most crucially of all, the nature of portraiture itself had fundamentally changed since pastel’s rise to popularity in the 1710s. In an interesting reversal of the process of imitation that saw early pastellists attempting to validate their work by making it more closely resemble oil paintings, artists were now taking their cue from pastels and endeavouring to render its unique effects in paint. The soft, suggestive finish of the Scottish painter Allan Ramsay, for example, is said to have been inspired by his close study of French pastel technique, in particular the work of Maurice Quentin de La Tour.

Gainsborough is undoubtedly the most interesting study in this regard. In Bath in the late 1760s and early 1770s, possibly inspired by or in competition with his friend and main rival William Hoare, Gainsborough produced and sold a number of finished pastel portraits. Several examples of the numerous landscape studies he also executed in both natural chalk and coloured pastel in the later 1770s now reside with the Tate. While Gainsborough’s work in pastel was relatively conservative, it fed back into his innovative technical experiments, in which he essentially erased the boundaries between different media; mixing chalk and oil paint together in single works on both canvas and paper.

Translated into Gainsborough’s large-scale oil portraits, the artist’s experience with pastel arguably expressed itself in the ‘hatching manner’ and ‘odd scratches and marks’ which Joshua Reynolds designated as a ‘novelty and peculiarity’ of his rival’s manner.19 Gainsborough’s occasional addition of ground glass to his oil paint can also be read as an attempt to capture, in a quite literal sense, the ‘glitter’ of glazed pastel works remarked on by exhibition critics (oil paintings, on the contrary, were displayed unglazed). However, his experiments with pastel perhaps left their deepest mark in his unusual application of colour. His ‘manner of leaving the colours’ as Reynolds framed it – more explicitly the way in which he utilised strokes of unmixed paint, to be blended by the viewer’s eye at the appropriate distance – echoes the pastel manual writer John Imison’s recommended treatment of pastel pigments:

… in crayon-painting it is often best to compound the mixed colours upon the picture, such as blue and yellow instead of green; blue and carmine instead of purple; red and yellow instead of orange…The beauty of a crayon picture consists in one colour shewing itself through, or rather, between another.20

While this imitation was a triumph of sorts, it also rendered pastel somewhat obsolete. With the reproduction of its novel effects in the more prestigious and durable medium of oil paint, pastel had lost one of its most important selling points. It was never to regain its former status and its contemporary impact has now been largely forgotten. Tellingly, works in pastel in public collections are rarely displayed or lent. Yet, in the particular brilliance of Gainsborough who, in the later decades of the 18th century brought elements of the increasingly unfashionable art of pastel back to the leading edge of contemporary practice, the influence of the craze for pastel lives on.