Francis Picabia

The Handsome Pork Butcher

Transcript

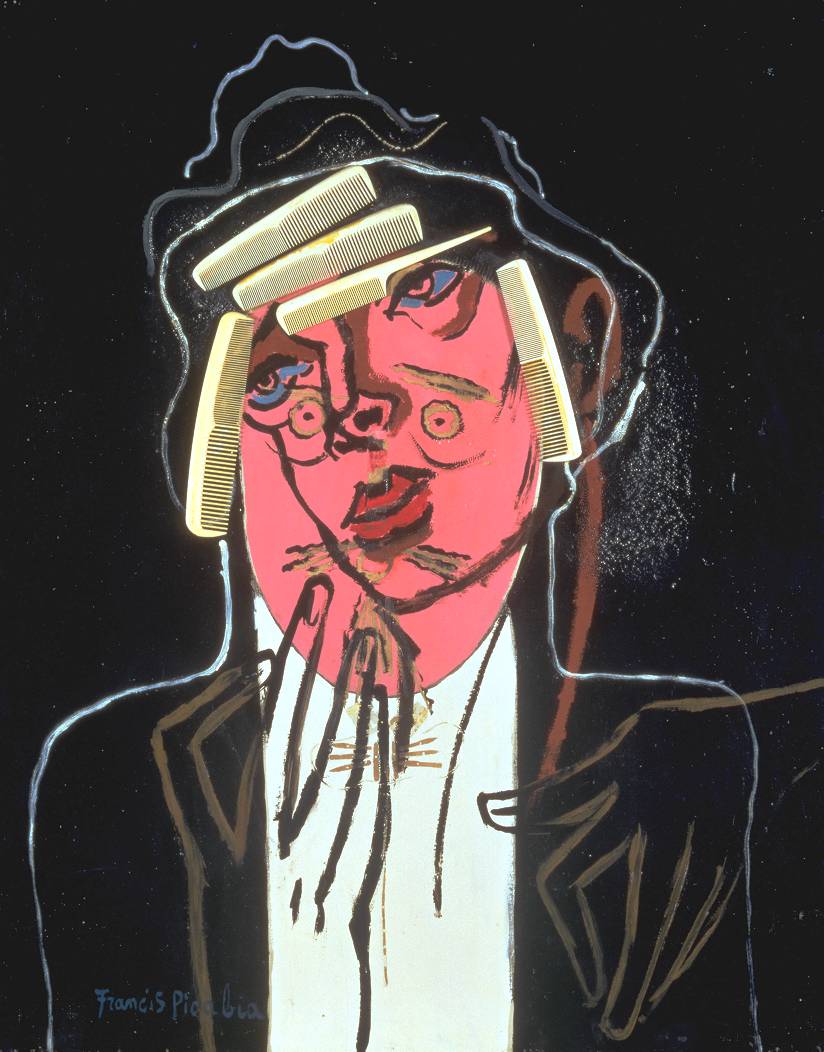

The Handsome Pork Butcher is in fact two portraits in one. Picabia has superimposed the face and hands of a woman over the top of the head and chest of a man. If we remove the woman, it becomes easier to make out the male form.

The man seems to be wearing a dinner jacket, but where normally this would give an impression of glamour or sophistication, Picabia’s subject looks comically insubstantial. His lurid pink face is set on top of a thick, vertical white strip that is his shirtfront. Without a neck in between, his florid head looks like an egg in an eggcup. A thin brown line running down the centre of his shirt and a bow tie are the only details on his clothing. The tie is represented in a very similar way to the moustache and mouth above it, with three straight lines either side of a simplified knot.

Set against a black background, his body, in its black dinner jacket, is differentiated from the space around it only by a crude, dirty white line which describes a thick, bullish neck, straight-across shoulders and straight-down arms. This thin, uncertain line makes his presence seem rather tenuous, as if only a single thread prevents him from being engulfed by the darkness around him.

Picabia has simplified the man’s face, making no attempt to model its shape or give it a sense of bone structure. Consequently his large flat pink oval head is cartoon-like rather than naturalistic. This quality is heightened by the way his features have been represented. Each feature is economically described in a thin dark line that roughly overlaps a thicker but much paler version of itself. Instead of emphasising and fixing the features in place, it gives the face a tentative and scruffy feeling.

The eyes are simply circles with a dot in the centre. Under each eye, giving the subject a jaded air, are two arched lines, drawn swiftly over the rough surface so that the swooping line of paint is broken rather than solid. Above his left eye, the right eye as we look at it, are two sharply angled parallel lines which contribute to an anxious expression.

The nose itself is not drawn in, but where it would be the paint surface is particularly distressed and grainy. At the base of this disrupted strip of paint is his mouth, a small circle similar in size to those that represent his eyes. It gives the impression that his lips are pinched together, as if making an ‘Ooooo’ sound or blowing out air. This curious expression only adds to our sense that the figure is flustered. Finally, radiating out from either side and below the mouth are three groups of three straight lines. They are drawn as a child might draw a cat’s whiskers, but here represent a neat moustache and a goatee beard.

Perhaps the most striking thing about the man is the collection of plastic combs around his head in place of hair. The combs provide the only remaining link to the original collage made between 1924 and 1926. When Picabia first created this work, it was covered with found objects.

Picasso and Braque are the first artists credited with using collage in fine art, incorporating printed papers and fabrics in their work to subvert and challenge traditional ideas of representation. Picabia, by contrast, used collage as a way of introducing humorous, symbolic and even political meaning. In the original version of the Handsome Pork Butcher, a different set of combs, six in total, represented the man’s hair.

His moustache, goatee and eyebrows were wooden toothpicks. His eyes and mouth were curtain rings and his nose was about 10 centimetres of seamstresses’ measuring tape. The bags under his eyes were darning needles and his bow tie was made from pen nibs. The painting’s original frame is now lost, but it was made from corrugated cardboard and sandpaper. The paint itself is household gloss paint, which in addition to being shiny, has wrinkled in places where different layers have dried unevenly. By choosing these cheaply manufactured domestic products, Picabia mocks the refined world of traditional academic painting. He refuses to use expensive materials, a noble pose and a heavy gilt frame to elevate his subject, bringing the genre of portraiture down to earth with a bump.

The man in this painting may not be as anonymous as he first appears. In 1926 the artist El Lissitzky exhibited this work and in a letter described it as a portrait of Raymond Poincaré. Poincaré was an intellectual, a member of the French Academy, President of France and twice Prime Minister in the 1920s. Traditionally, someone of that political and social status would expect their portrait to be very flattering. Such a portrait would be constructed to convince both the contemporary and future viewer that Poincaré was an attractive and cultured man of power and influence.

However, Picabia and his Surrealist friends were hostile to Poincaré. The leader of the Surrealist movement, Andre Breton declared; ‘We consider the presence of Monsieur Poincaré at the head of the French government to be a serious obstacle to all serious thought, an almost gratuitous insult to the spirit and a ferocious joke which should not be allowed to pass.’

Surviving photographs of Poincaré do bear a resemblance to the pink-faced man in Picabia’s painting. But whether or not this is a portrait of a specific public figure, it still manages to lampoon artistic convention, declaring it through collage to be quite literally, rubbish.

In around 1934-35, Picabia returned to the Handsome Pork Butcher and reworked it extensively. He pulled off all of the collage elements and in doing so created rough patches where the paint was disrupted. The man’s features remained visible in the yellowing glue and exposed canvas that the objects left behind, and Picabia made them more obvious by painting thin dark lines over the top.

But the most radical change was his decision to paint the second portrait, that of the woman, over the top of the existing one. Picabia began creating works made up of multiple, overlapping images in the late 20s. He called them ‘Transparency’ paintings and the aim was to evoke a dream-like quality as the images combined and unexpected associations developed as the lines of each layer jostled for the viewer’s attention.

The presence of the woman dramatically complicates the image. She also increases the humour since her placement encourages us to see an interaction between the two figures. Her head lies over his, although there is a slight slippage caused by her being shown in three quarter profile and he head on. As a consequence their mouths teasingly almost touch and her languid, heavy lidded gaze sits above his startled eyes, as she gazes enigmatically out towards the left hand side of the painting. Finally, her long fingers appear to be running over his shoulder and across his chest, providing one explanation for his anxious expression and pursed lips.

She also introduces additional colours into the painting beyond the black, white and bright pink of the male figure, with the bright almost synthetic blue of her eyes and the vampish scarlet of her full lips. Her features are outlined in thick, uneven lines. Those that outline her neck and left ear are painted in a warm terracotta, while her face and expressive hands are drawn in a darker brown. We have represented these browns in shades of grey here, so that that we can view the lines more clearly against the black background.

Unlike the man, her face is slightly, albeit very crudely modelled. There is shading under her left eye and above her right, as well as shadow around the left side of her nose and below her bottom lip. This gives her sketchy face some substance and three-dimensionality, which helps her to assert her presence against the bright pink of the man’s face beneath.

The title of this painting has also gone through transition. At exhibition in 1927 it was simply called Portrait. However, by the time it was exhibited in Paris in 1949, it had acquired its current title. The critic Guilleme Apollinaire, who knew Picabia, wrote that his titles were not intellectually separate from their works. Instead they "play the part of an inner frame…to ward off decadent intellectualism."

The title The Handsome Pork Butcher acts as a trigger for humorous and surreal associations. It is difficult not to link the idea of a pork butcher with the ham-like pink face of the man, or to contrast the word ‘handsome’ with the dishevelled, harried appearance and the predatory encroachment of the vampish woman. Although no single explanation can be attributed to the relationship between the title and the content of the work, Picabia is certainly using it to further deflate the pompous traditions of portraiture.