Floating Worlds June 2002

Paul Bonaventura

In a recent article for Prospect magazine, cineaste Mark Cousins outlined the three possibilities of what film can be. Up until the 1940s, he said, movie-making was mostly characterised by formalism. It was acknowledged that there was something fundamentally unreal about the nature of cinema during its evolutionary phase, and films from that period were likened to dreams. Paraphrasing the influential art critic Clement Greenberg, Cousins went on to suggest it was not the job of cinema back then to describe the outside world so much as generate its own world. Cinema was an entirely new medium and came with its own set of aesthetic principles.

With the increasing maturity of the industry, after the Second World War, formalism gave way to realism, but it was also allowed that cinema could be a vehicle for personal expression. The director might write with a camera as an author does with a pen, and personal expression transformed into authorship theory, encouraging directors to think of themselves as artists.

Cousins based his essay on the findings of four French theorists, Robert Brasillach and Maurice Bardèche, authors of the highly influential Histoire du Cinéma, André Bazin and Alexandre Astruc. Looking back at their work today, most experts would say that none of them were right. Each of them, in some way, expressed a separate truth about cinema and their ideas form a triangle within which every film could be positioned. ‘But there is a deeper truth,’ concludes Cousins, ‘informing all the points in the triangle. This is the geometry of the triangle: film is just a language. And like a language, it can do technical, realistic and expressive things, but there's nothing innately formal or realistic in it. It is reality neutral.’

In 1992, the year in which the Oscar for Best Picture went to Clint Eastwood’s technical, realistic and expressive western Unforgiven, the European Organisation for Nuclear Research launched the world wide web. Since its unveiling, the web has come on at an astonishing rate, and the growth in users has been nothing short of extraordinary, yet the medium is still in its infancy. If, as a conceit, we were to compare the story of the web with the story of cinema, we might expect the web to be dominated at this early stage in its development by revolutionary inventions of a formalist or realist kind. Without the technical impulses of the pioneers, there would be no foundation for the web to build on, and certainly the medium has a genius for realism, but what has been remarkable in its short history is just how rapidly the web has been colonised by the exponents of personal expression. Like cinema then, and within a decade of its birth, the web has become reality neutral.

Arguably, no art work encapsulates the reality neutral position of the web quite so succinctly as Tate in Space. Formally, the site presents us with no radical surprises, based as it is on the existing graphic identity of Tate Online. Indeed, our belief in the veracity of Tate in Space is predicated on the optical and conceptual fit between the new division of Tate and its four earthbound siblings. Similarly, the database and network technologies which the project currently makes use of have been around for years.

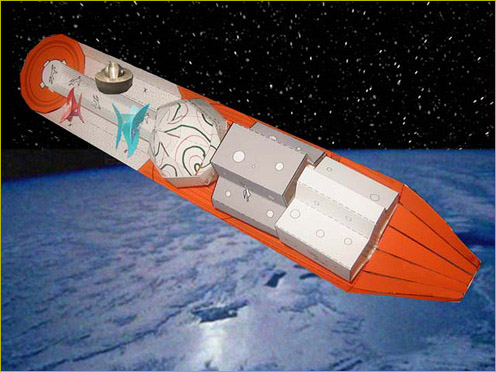

But what of the site content? Are we really expected to believe that the Tate Satellite is up there in orbit, transmitting information back to earth in the manner of a latter-day Sputnik? Is there any possibility that the intended space station will be realised in our lifetimes? And what of Tate’s cultural-imperial aspirations? Is it true that the project has the sanction of Tate’s Trustees? Have they determined that the next Tate should be in space? And has the artist Susan Collins actually been taken on as director of the organisation’s online programme? If any of this is genuine then the apparent competition to bring contemporary art to audiences worldwide, once the prerogative of the mighty Guggenheim empire, has suddenly thrown up a new race leader. Freed of its terrestrial origins, Tate has gone one better than its nearest rival by pitching its activities at a new generation of museum visitors, many of which have yet to be born (on earth or elsewhere).

The earlier correlation between cinema and the web isn’t as fanciful as it might at first appear. Many browsers on the Tate in Space site, at some point in their visit, will find themselves recalling the 1998 film version of the cult television series Lost in Space, or possibly the original series itself, and the make-believe nature of the project also elicits comparison with movies like Forbidden Planet and Fantastic Voyage. But surely the closest cinematic parallel with Tate in Space is Peter Hyams’s conspiracy theory masterpiece Capricorn One. In Capricorn One, James Brolin, Sam Waterston and OJ Simpson star as three astronauts who agree to spare the government embarrassment by faking their historic landing on Mars after their spacecraft is deemed to be unsafe. When a scheming mission controller plots to kill the astronauts in a staged capsule fire, the trio embarks on a mission to expose the truth.

In the world of cinema, reality isn’t immutable. Movies have constantly messed around with the truth in the search for creative inspiration. Cousins confirms that audiences will readily lap up the truth-bending fabrications of film because they want to believe in things beyond their immediate comprehension. ‘Many agree with über-screenwriter William Goldman’s formulation,’ he continues, ‘that in movies it doesn’t matter what is true, what is important is what appears to be true.’ As for the movies so with the web. Anyone who spends time on the Tate in Space website will cling to the hope that the new branch of Tate is authentic, and that even if Collins is being a little economical with the actuality, there is always the possibility that things will really take off at some future date.

Notwithstanding, Collins’s project is less to do with real or imagined artefacts in space or opportunities for artists outside the earth's gravitational pull and more about examining the contexts in which art institutions, artists and viewers play out their interconnecting roles. Tate in Space touches on matters to do with access and social inclusion, interpretation and the search for intellectual and moral authenticity. It explores the idea of a reality which, for the time being, we can only experience remotely and examines how institutions might imaginatively overcome the limitations imposed on them by virtue of their bricks-and-mortar locations. Furthermore, it extends the debate surrounding the nature of contemporary art and its presentation, and makes use of recent technologies to expand and advance the notion of presence.

Indeed, if we are in the right place at the right time, and believe hard enough in the overall proposition, we might get lucky and see the trailblazing Satellite arcing its way across the inky heavens. The Tate in Space website provides accurate information on the trajectory of the Satellite, orbiting the planet at a velocity of 7.67 km/sec approximately 400km above the surface in a polar-to-polar low earth orbit. And what’s so strange about a large-scale organisation having its own dedicated satellite these days? After all, you can send one up for less than a quarter of a million pounds at the moment, approximately 12% of Tate’s annual art purchasing budget, and a sum far below the cost of an average canvas by Matisse or Pollock.

What Collins is suggesting ultimately with her Tate in Space project is that standpoint is everything. As if to underline this message, the artist has made a request on one section of the site for anyone who thinks they might have witnessed the Tate Satellite in orbit to submit evidence of their sighting. In a truly democratic gesture, the artist has co-opted audiences to assist her in the fabrication of a reality where none supposedly exists.

Of course the site is illusory. If Tate really had launched its own Satellite, you can be sure that it would have been front-page news in all the world’s press. Yet Collins has elected to give the site as much authority as possible. Fiction has always played a big part in the artist’s work, but with this project she has excelled herself, creating a fake component of a real organisation with all the trappings of authenticity. But who’s to say what might transpire in the next ten, twenty or fifty years? Although Tate in Space has come on stream with far less fanfare than Tate Britain or Tate Modern, Tate Liverpool or Tate St Ives, it has the potential, in time, to be infinitely more influential than any of its seemingly more prestigious forebears.

Paul Bonaventura, Senior Research Fellow in Fine Art Studies, University of Oxford

Net Art commission by Susan Collins, touching on matters to do with access, social inclusion, interpretation and the search for intellectual and moral authenticity.