Robert Rauschenberg

Born 22 October, 1925 Port Arthur, TexasDied 12 May, 2008 Captiva, Florida

An American artist of the twentieth century who created his own path, redefining how art could be made and what it could be. He worked in collaboration with many pioneering artists, painters, dancers, composers and activists to create artworks that elevated the everyday. He shared his spirit and influenced the art world that came after him, in painting, printmaking, performance and protest.

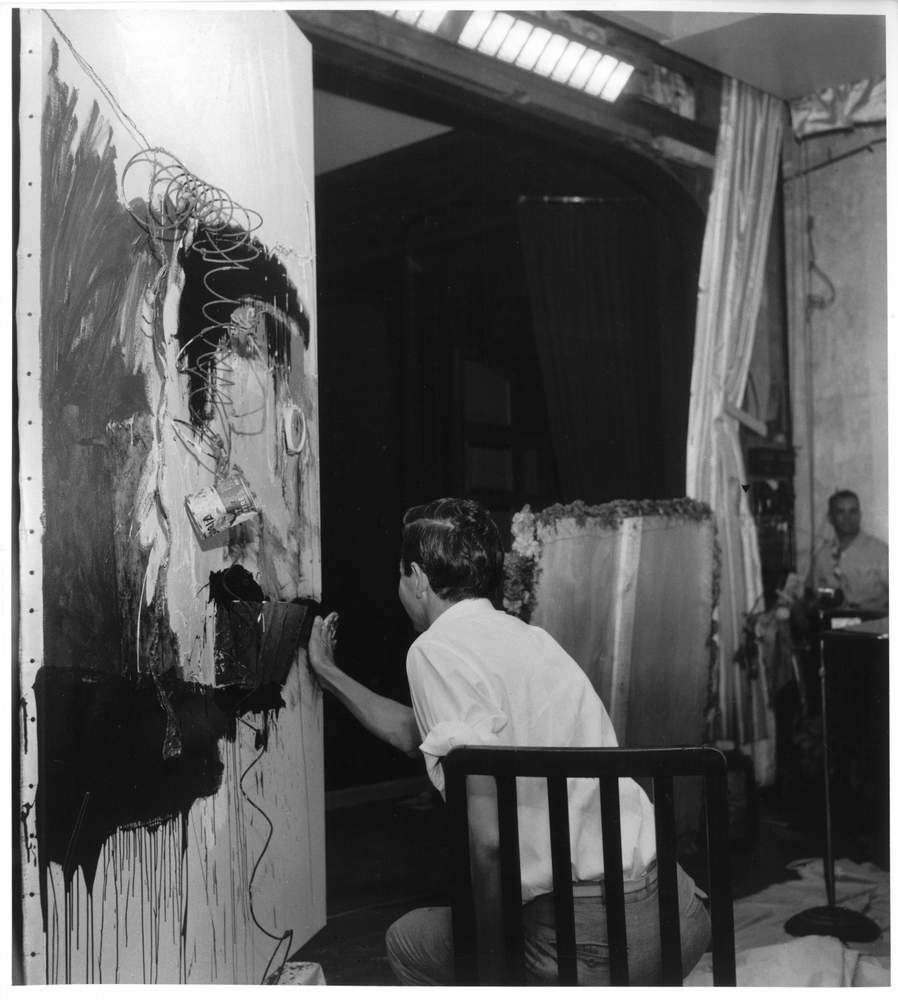

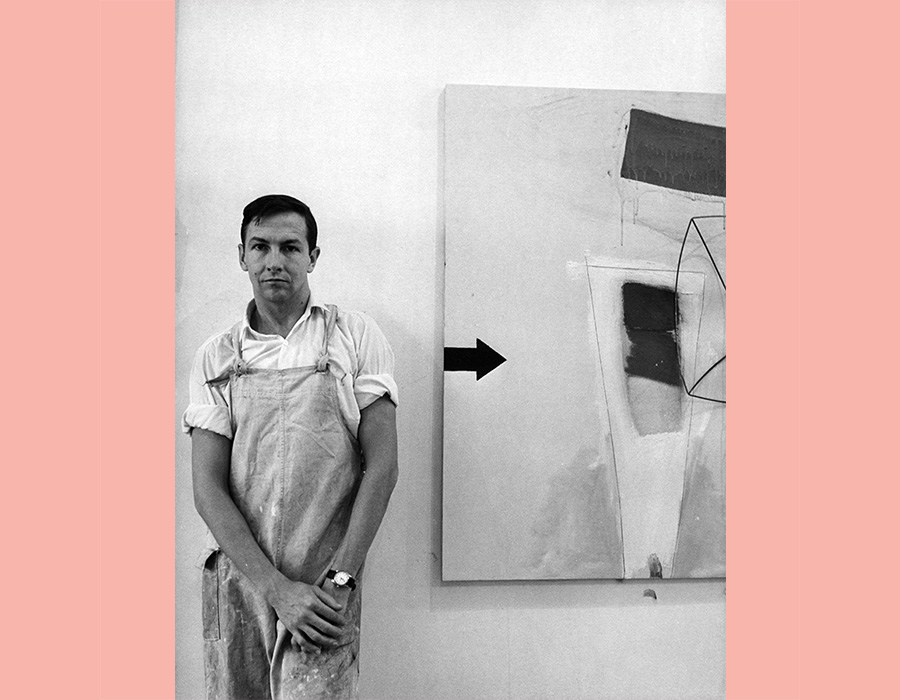

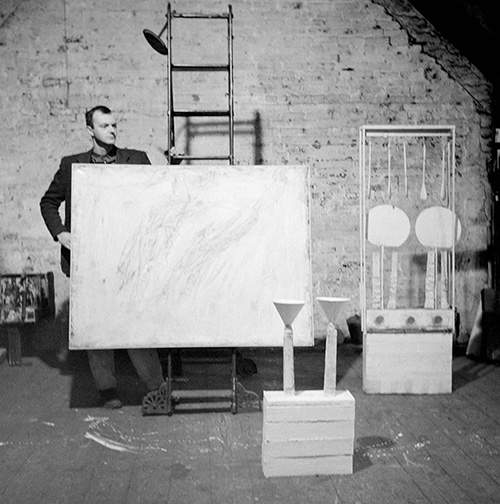

Rauschenberg in his Broadway studio with Stripper 1962, New York, c.1962 Photo: Unattributed

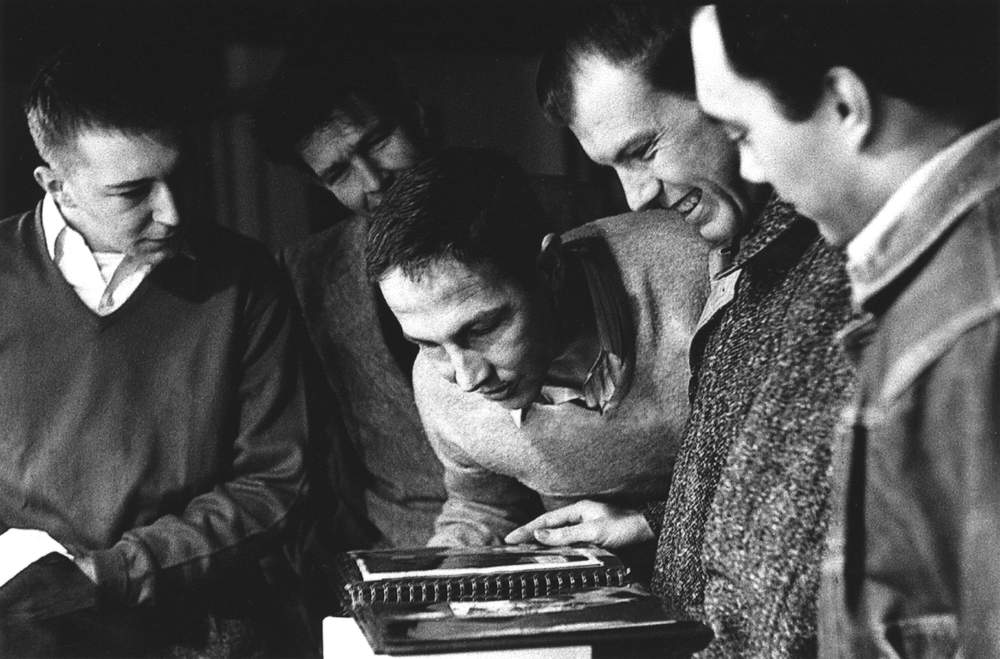

Alex Hay, Rauschenberg, Steve Paxton and Trisha Brown rehearsing Spring Training in Rauschenberg’s Broadway studio, New York, 1965 Photo: Ugo Mulas © Ugo Mulas Heirs

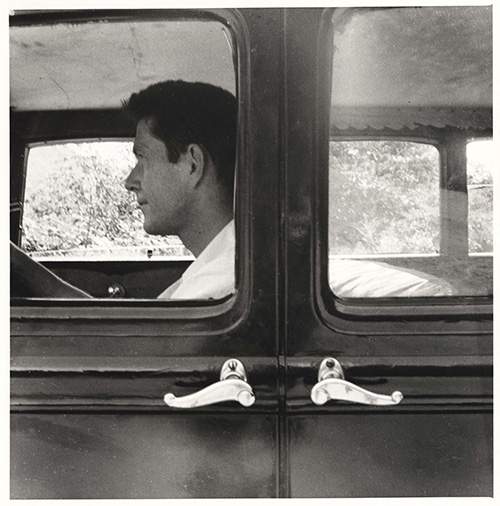

Rauschenberg, c.1964 Photo: Saulnier

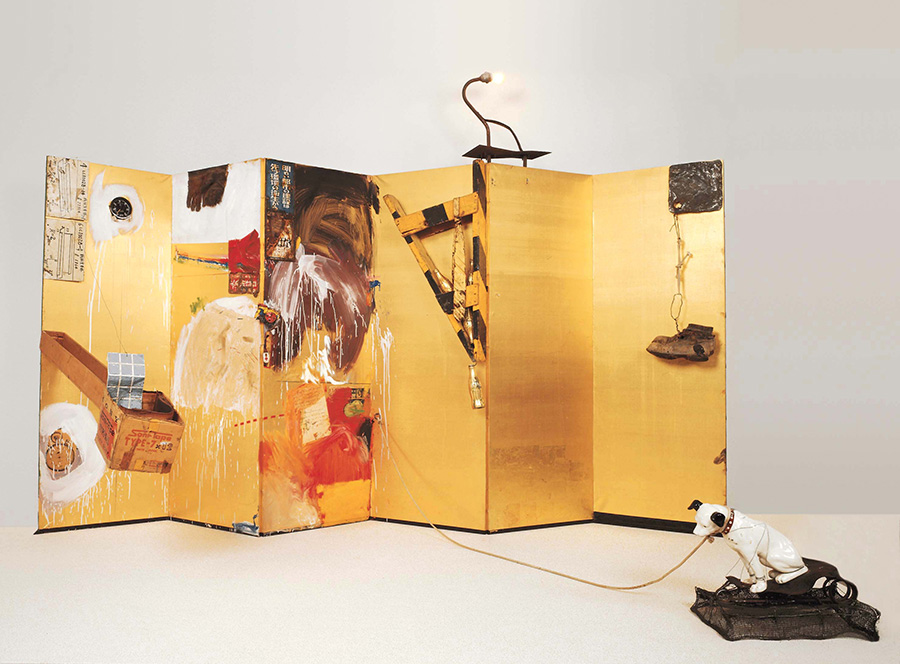

Gold Standard 1964 © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

Pilot (Jammer) 1976 © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

Rauschenberg performing Elgin Tie at Five New York Evenings, Moderna Museet, Stockholm, 13 September, 1964 Photo: Hans Malmberg

Balcone Glut (Neapolitan) 1987 © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

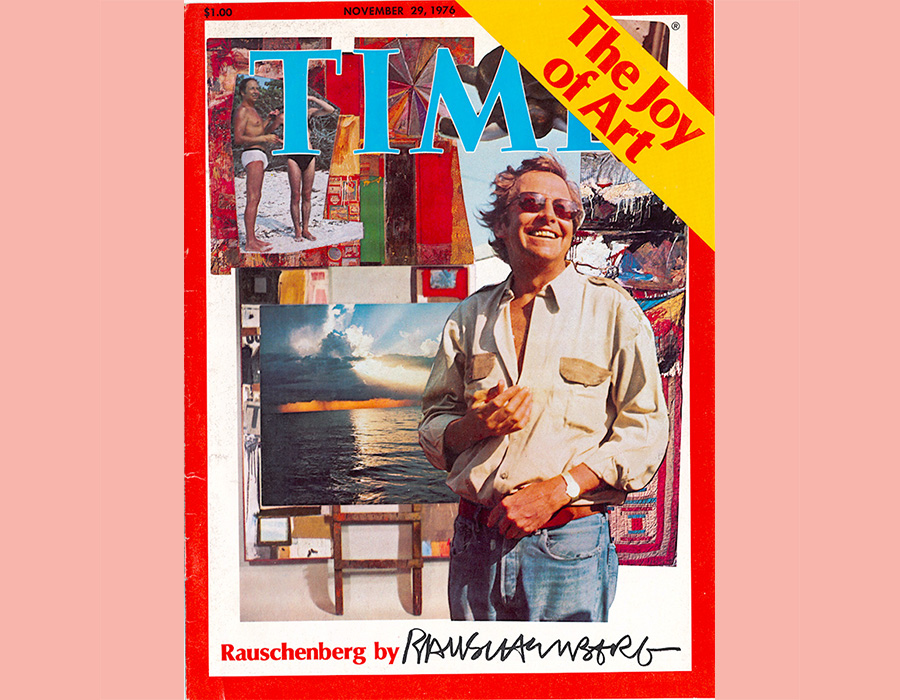

Robert Rauschenberg, Time magazine cover, 29 November 1976 © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

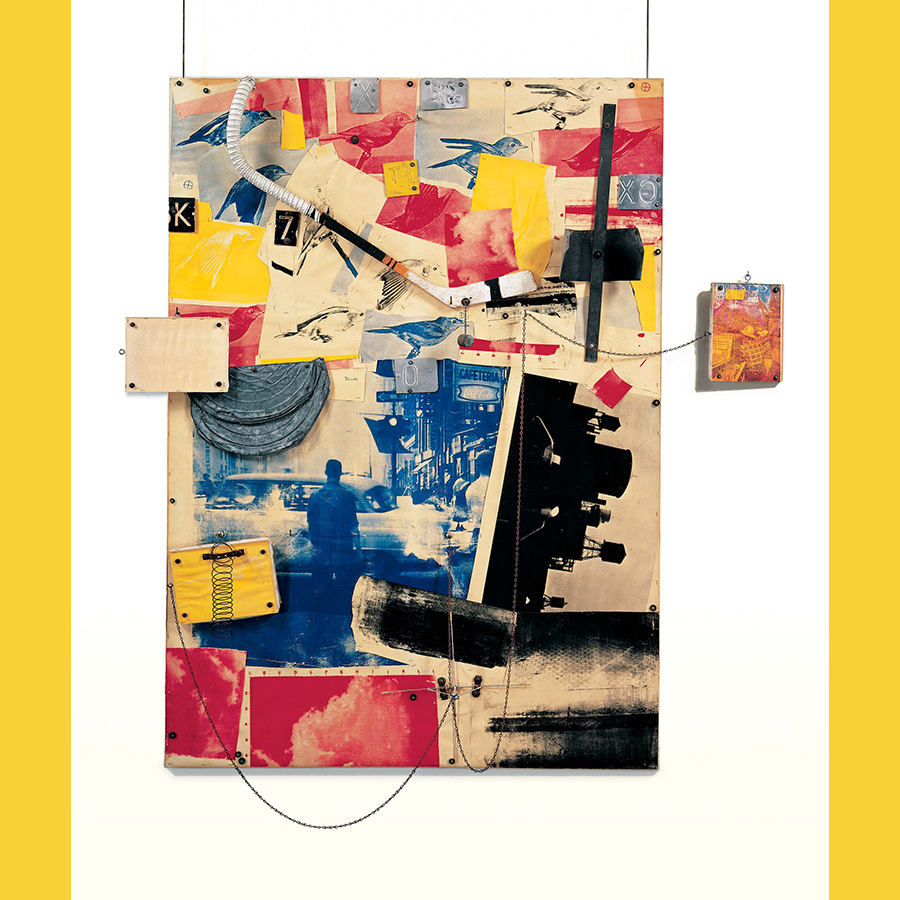

Global Loft (Spread) 1979 © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

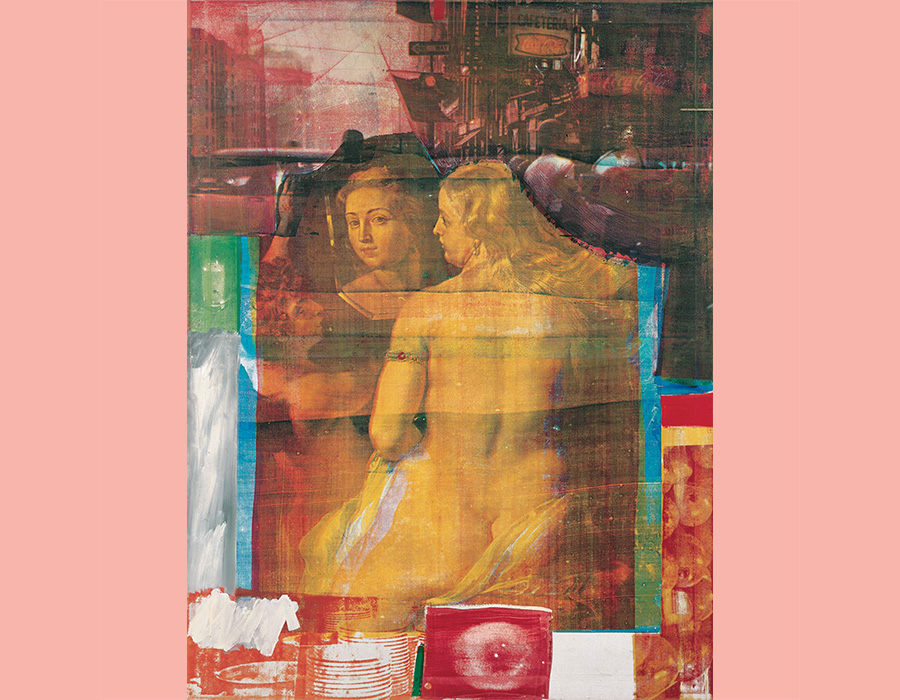

Persimmon 1964 © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

National Spinning / Red / Spring (Cardboard) 1971 © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

Glacier (Hoarfrost) 1974 © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

Rauschenberg working on L.A. Uncovered series, Gemini G.E.L., Los Angeles, 1998 Photo: Sidney B. Felsen © 1998

Oracle 1965 © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

Read on to learn from the master...

‘I was considered slow. While my classmates were reading their textbooks, I drew in the margin’

While Rauschenberg studied at some of the most well-known art schools, under influential teachers, he always paired this with learning from the world and people around him.

WHITE PAINTING 1951

While learning from those around him, Rauschenberg also inspired others with his work.

‘The White Paintings were airports for the lights, shadows, and [dust] particles.’

Rauschenberg wanted to create paintings that looked as if they were untouched by human hands and even allowed the works themselves to be remade without his direct involvement. These canvases, painted entirely in white, reflect the chance effects of changes in the light and shadows.

Seeing Rauschenberg ’s White Paintings inspired composer John Cage to fully explore silence in his own work. Cage often worked with found sound, but credited the White Paintings with leading eventually to his most famous piece 4’33’’, where no sound is played by the musicians performing it.

‘That's why I like dance, music, theatre, and that's why I like printmaking, because none of these things can exist as solo endeavors. Also, the best way to know people is to work with them, and that's a very sensitive form of intimacy.’

SHORT CIRCUIT 1955

‘Rauschenberg was invited to participate in the Fourth Annual Painting and Sculpture Show at the Stable Gallery; some artists he wanted included were not. So Bob made a Combine – he called it Short Circuit – which incorporated works by the refusés: Jasper Johns and Bob’s former wife, Susan Weil.’

Family Album

Susan Weil

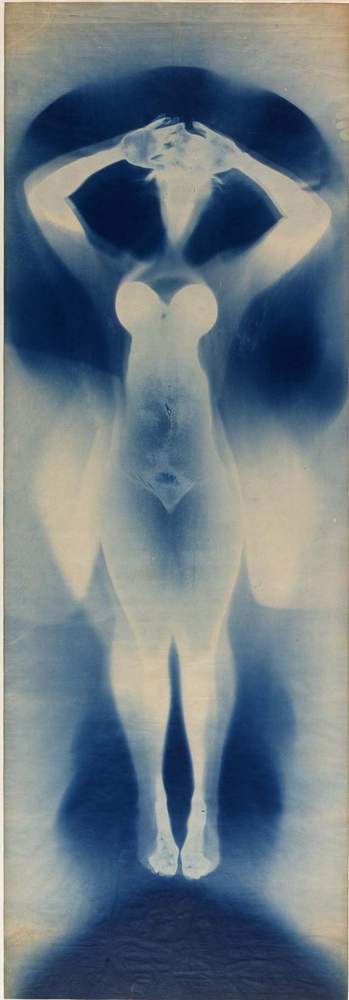

Painter, printmaker and book artist Susan Weil met Rauschenberg in 1948 studying at the Académie Julian in Paris. They enrolled together at Black Mountain College, North Carolina, and the Art Students League, New York. They were married from 1950 to 1952 and collaborated on various art and commercial projects.

Susan Weil and Rauschenberg, Black Mountain College, North Carolina, 1949 Photo: Trude Guermonprez

Susan Weil and Rauschenberg on their wedding day with members of their wedding party: James Leonard Weil, Donald Droll, and Janet Begneaud. Outer Island, Connecticut, June 1950

Susan Weil and Robert Rauschenberg in Paris, 1948

Jasper Johns

Artist, famous for his flag paintings, and widely regarded as a forerunner of pop art. From their meeting in 1951 they became partners and collaborators, working and living together for a number of years.

Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns in Johns’s Pearl Street studio, New York, c.1954 Photo: Rachel Rosenthal

Jasper Johns and Rauschenberg, Gemini G.E.L., Los Angeles, 1980 Photo: Terry Van Brunt

Untitled (Jasper, Pearl Street Studio) 1955 Photo: Robert Rauschenberg

Cy Twombly

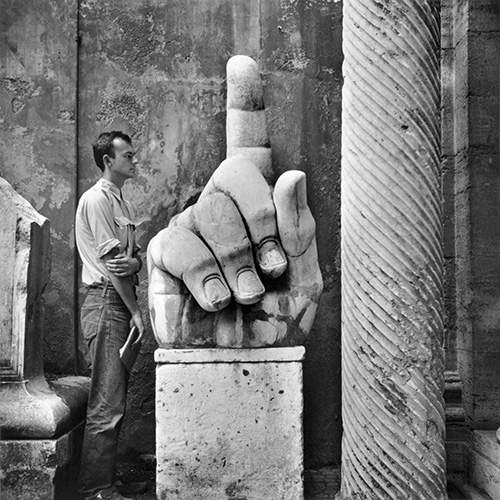

Painter, renowned for using expressive handwriting and scratching in his paintings. He met Rauschenberg in 1951 in New York and they travelled to Europe and Africa together, becoming lovers, and lifelong friends.

Rauschenberg (left) and Cy Twombly (seated) returning from Italy to New York City aboard SS Andrea Doria with fellow passenger Kurt Osinski (right), April 1953 Photo: Edith Osinski

Cy + Relics, Rome 1952 Photo: Robert Rauschenberg

Untitled (Cy with his artwork, Rauschenberg's Fulton Street Studio) 1954 Photo: Robert Rauschenberg

Merce Cunningham & John Cage

Rauschenberg first met composer John Cage in New York in the early 1950s. He then studied with Cage and Cunningham at Black Mountain College. Rauschenberg travelled with the Cunningham Dance Company as a collaborator and costume and set designer. They maintained a close relationship throughout their careers.

Untitled (John Cage, Black Mountain) 1952 Photo: Robert Rauschenberg

Costumes by Remy Charlip in collaboration with Rauschenberg, Ray Johnson and Vera Williams for Merce Cunningham Dance Company's Springweather and People 1955. Pictured: Merce Cunningham and Carolyn Brown. Photo: Louis Stevenson

Costumes by Rauschenberg for Merce Cunningham Dance Company’s Antic Meet 1958 at Five New York Evenings, Moderna Museet, Stockholm, September 1964. Pictured: Carolyn Brown and Merce Cunningham. Photo: Hans Malmberg

Participating in composer John Cage’s Theatre Piece #1 (sometimes referred to as the first happening) in the dining hall of Black Mountain College in 1952 began Rauschenberg's involvement with performance.

Later, on tour with the Cunningham Dance Company, Rauschenberg developed the idea of ‘live decor’, making new scenery and sets through his own found objects and improvised actions for each performance, including painting backdrops as the dancers performed or even ironing costumes at the back of the stage.

Set and costumes designed by Rauschenberg for Merce Cunningham Dance Company’s Interscape 2000. Pictured: Jeannie Steele, Derry Swan, Maydelle Fason, and Holley Farmer. Photo: Ed Chappell

Set, costumes, and lighting by Rauschenberg for Merce Cunningham Dance Company’s Nocturnes 1956. Pictured: Carolyn Brown performing a lift with members of the ensemble. Photo: Oscar Bailey.

Set and costumes by Rauschenberg for Paul Taylor Dance Company’s Images and Reflections 1958. Pictured: Maggie Newman and Taylor. Photo: Unattributed.

Minutiae 1954 © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

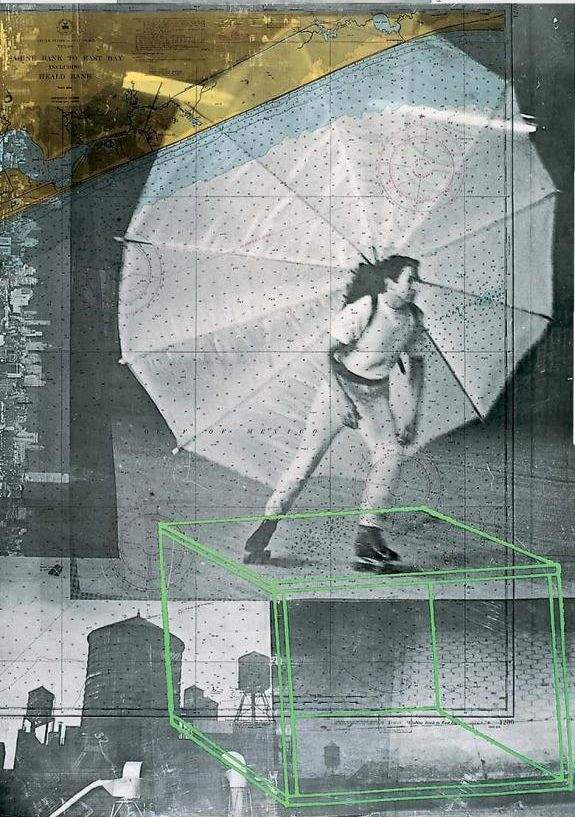

Set designed by Rauschenberg for Trisha Brown Dance Company’s Lateral Pass 1985 at Napoli Teatro di San Carlo, Naples, January 1987. Photo: Luciano Romano.

Costumes and set, entitled Tantric Geography, designed by Rauschenberg for Merce Cunningham Dance Company’s Travelogue 1977. Photo: Charles Atlas.

‘The idea of having your own body and its activity be the material – that was really tempting.’

Throughout his career, Rauschenberg collaborated with dancers and choreographers.

As well as designing sets, costumes, and lighting for Cunningham and other choreographers such as Trisha Brown and Paul Taylor, Rauschenberg also performed and choreographed his own performance works and often incorporated a theatrical element into his other works.

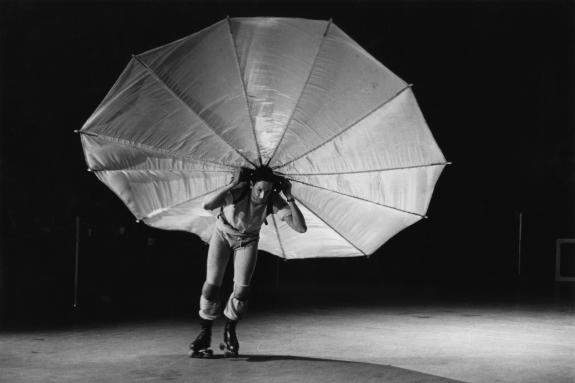

PELICAN 1963

‘Pelican ... marked Rauschenberg's unexpected debut as a choreographer ... listed [mistakenly] in the program as 'choreographer', he decided to take on the challenge.’

Excerpts from Rauschenberg’s performances, including Pelican 1963, Map Room II 1965 and Spring Training 1965 compiled by the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, 1997. Courtesy Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

‘A pair of socks is no less suitable to make a painting with than wood, nails, turpentine, oil and fabric.’

GLUTS 1955

From 1986, Rauschenberg began a series known as Gluts. A native Texan himself, Rauschenberg was visiting Houston, and noted that the Texas economy was in recession due to a surplus or glut in the oil market – Texas's major export. He began to collect gas-station signs and other metal scrap from cars and industrial processes, transforming them into sculptures. ‘It’s a time of glut. Greed is rampant. I’m just exposing it, trying to wake people up. I simply want to present people with their ruins ...’ – quoted in Gluts Guggenheim Museum, New York, 2009

Balcone Glut (Neapolitan) 1987, Stop Side Early Winter Glut 1987, Greek Toy Glut (Neopolitan) 1987 © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

Bed 1955 © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

Bed 1955

Bed remains one of Rauschenberg’s most famous works – he used his own quilt as a surface to begin a painting.

He hoped to create an abstract artwork with it, but no matter how hard he tried he could not look at the piece without thinking of a bed. So, finally he gave in and put a pillow on it.

‘Because it was just a bed … no matter what I did, it was just a bed’– quoted in Robert Rauschenberg and Calvin Tomkins: A Conversation about Art and Life (2006)

Inside New York's Art World: Robert Rauschenberg and Leo Castelli 1977. Interviewer/producer Barbaralee Diamonstein-Spielvogel. Barbaralee Diamonstein-Spielvogel Collection, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University

‘The best part of my joy and adventure is that I don't have the foggiest idea about what I might be doing next, and I don't stay awake at night thinking about it.’

Combine

A term invented by Rauschenberg to describe a series of works that combine aspects of painting and sculpture. Combines can either hang on the wall or stand freely.

‘I wanted something other than what I could make myself and I wanted to use the surprise and the collectiveness and the generosity of finding surprises. And if it wasn’t a surprise at first, by the time I got through with it, it was. So the object itself was changed by its context and therefore it became a new thing.’

Robert Rauschenberg and Calvin Tomkins: A Conversation about Art and Life, moderated by Nan Rosenthal. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 5 February 2006

Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.)

In 1960, Rauschenberg began working with Bell Laboratories engineer Billy Klüver. In 1966, they organised 9 Evenings: Theatre and Engineering, which took place at the Armory in New York. Forty engineers and ten contemporary artists worked together to create performances using new technology.

Together with engineer Fred Waldhauer and artist Robert Whitman, Rauschenberg and Klüver formed E.A.T. The project aimed to develop links between artists and technologists and engineers, to find new creative possibilities.

Herb Schneider, Rauschenberg, Lucinda Childs, L.J. Robinson, Per Biorn and Billy Klüver in Berkeley Heights, NJ, preparing for 9 Evenings: Theatre and Engineering, Berkeley Heights, New Jersey, 1966. Photo: Unattributed

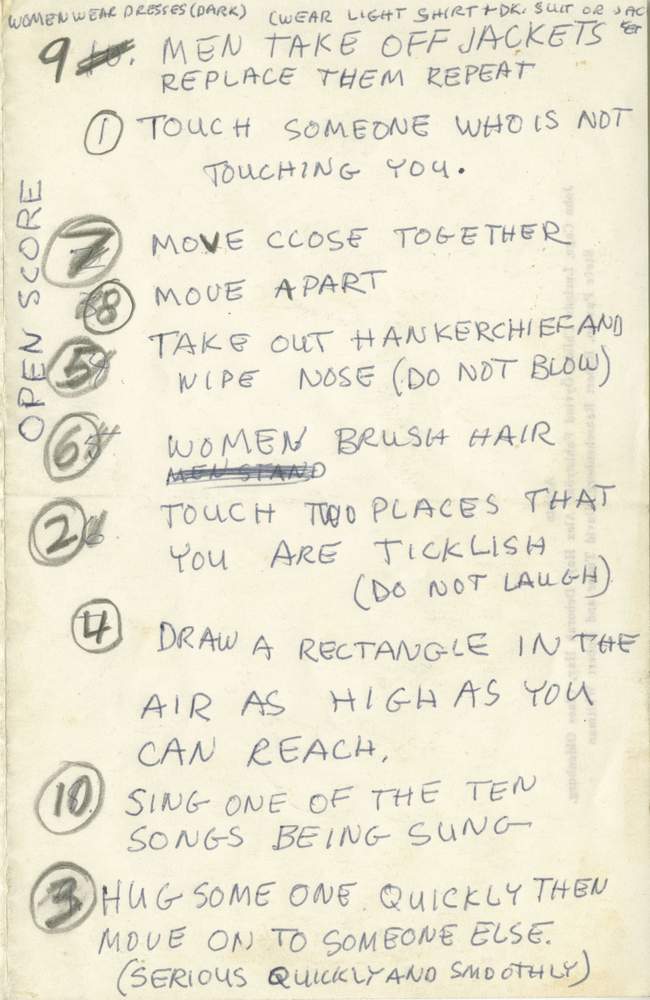

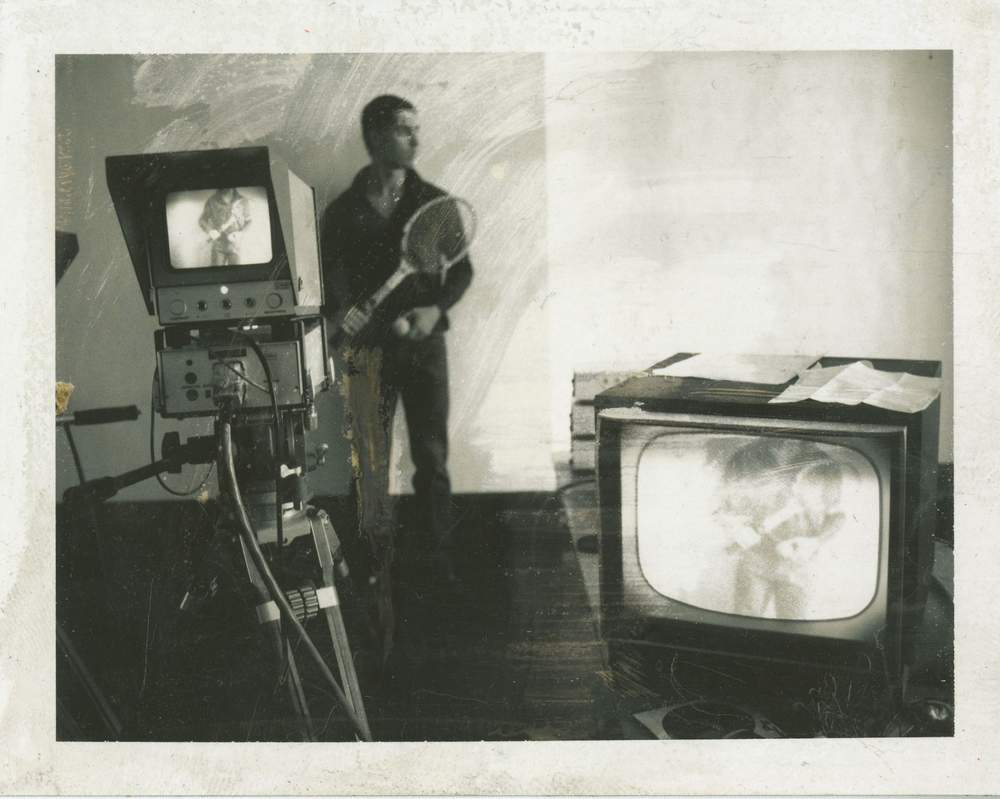

OPEN SCORE 1966

Rauschenberg and EAT presented Open Score at 9 Evenings.

As Rauschenberg explained in the programme notes:

‘My piece begins with an authentic tennis game with rackets wired for transmission of sound. The sound of the game will control the lights. The game's end is the moment the hall is totally dark. The darkness is illusionary. The hall is flooded with infra red (so far invisible to the human eye). A modestly choreographed cast of from 300 to 500 people will enter and be observed and projected by infra-red television on large screens for the audience.’

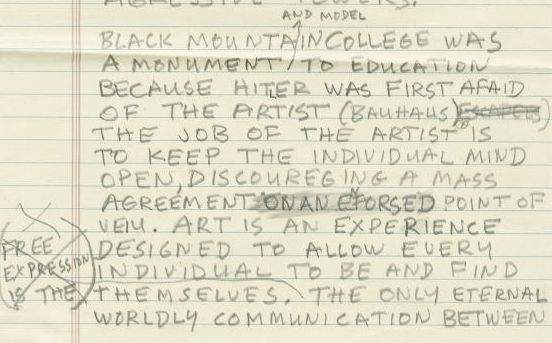

Rauschenberg’s handwritten notes detailing the actions to be performed onstage by an assembled cast of more than five hundred people during a portion of his performance Open Score 1966. Courtesy Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

Steve Paxton with sound-wired tennis racket and infrared television system for Rauschenberg’s Open Score 1966 Photo: Robert Rauschenberg.

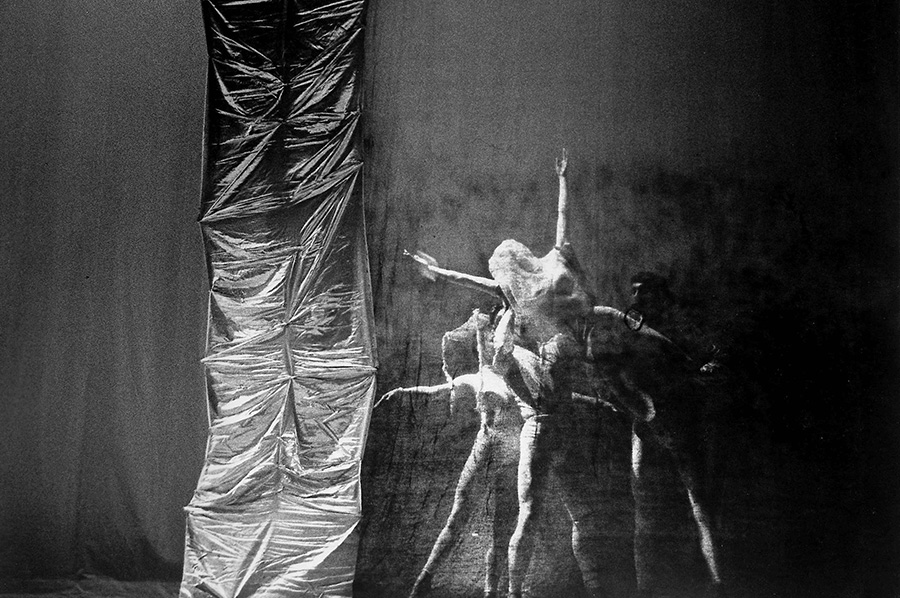

Open Score at 9 Evenings: Theater and Engineering 1966. Courtesy Julie Martin and Experiments in Art and Technology

Mud Muse 1968–71

Mud Muse 1968–71 © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

Rauschenberg continued to experiment with technology. In 1968 he began working on Mud Muse together with engineers Carl Adams, George Carr, Lewis Ellmore, Frank LaHaye and Jim Wilkinson.

The piece was inspired by the bubbling natural springs and geysers of Yellowstone National Park. The mixture in the tank bubbles and splatters in response to ambient noise, including the pre-recorded soundtrack (including birdsong and music), audience noise and the sound it makes itself.

‘People reached their fingers in and felt the mud, it was very silky. Then they started putting their whole hands in and making brown mud prints on the dove grey wall. One woman was about to jump in and do body prints on the wall. An exciting night. From then on, we had to put a guard at the entrance … to keep people out of the mud.’

Background images: E.A.T. news Vol. 1, no. 2 (1 June, 1967) New York: Experiments in Art and Technology 1967 Poster for 9 Evenings: Theatre & Engineering 1966 Mud Muse 1968–71 (detail)

‘I know that art has the energy to change minds and hearts. Art is a powerful source of fact and joy.’

‘I have discipline, I just go to work, and I work every day and I NEVER know what I’m doing.’

‘Screwing things up is a virtue. Being correct is never the point.’

‘Being right can stop all the momentum of a very interesting idea.’

Rauschenberg performing in Steve Paxton’s Jag vill gärna telefonera (I Would Like to Make a Phone Call) at Five New York Evenings, Moderna Museet, Stockholm, September 1964 Photo: Stig T. Karlsson

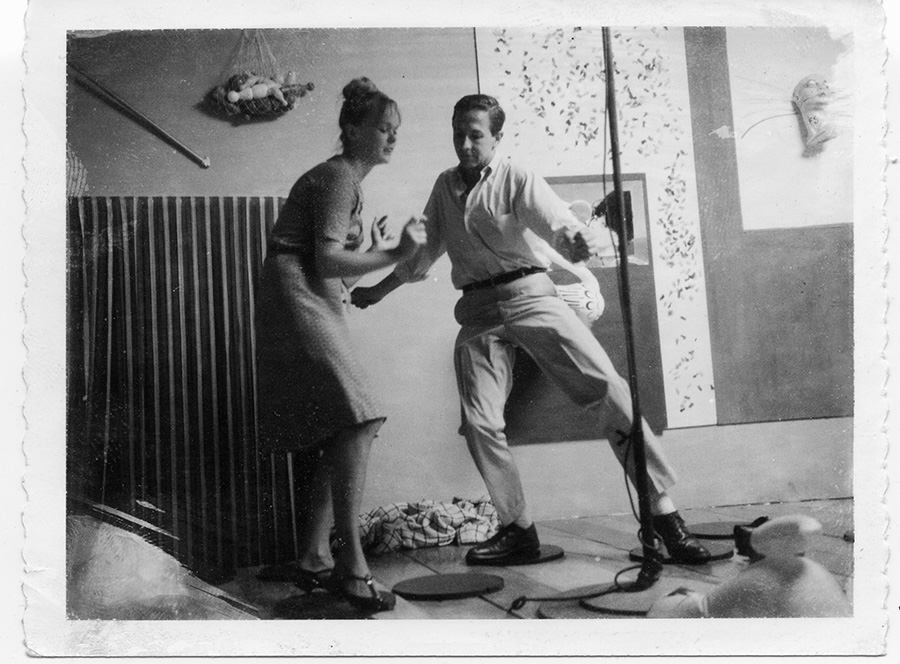

Rauschenberg and unidentified woman, dancing, Dylaby (Dynamisch Labyrint), Stedelijk Museum, September 1962. Photo: Billy Klüver

Rauschenberg in Captiva, Florida, 1978

Rauschenberg during a break for the proofing session for Stoned Moon 1969–70 lithograph series, Gemini G.E.L. parking lot, Los Angeles, 1969. Photo: Sidney B. Felsen © 1969

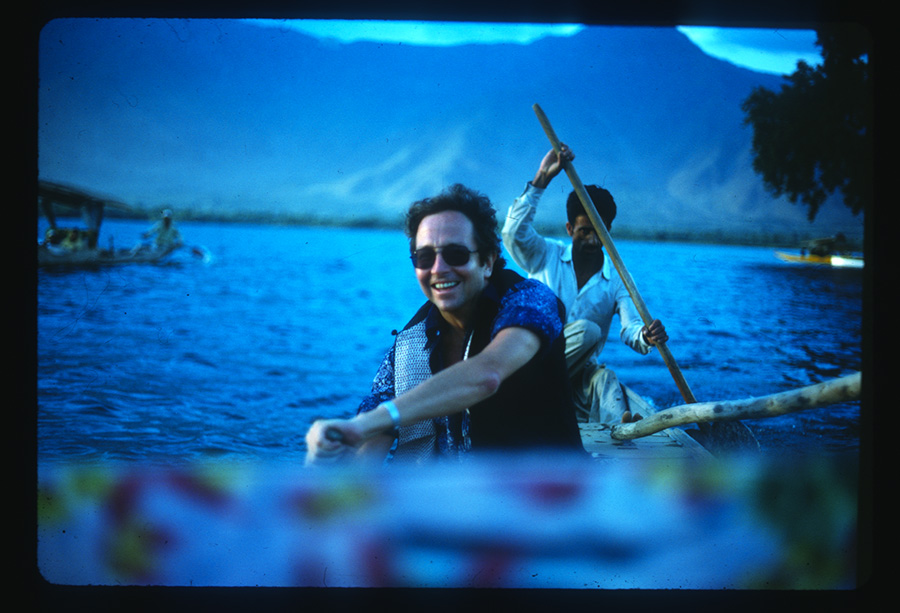

Rauschenberg in India, 1975. Photo: Hisachika Takahashi

Rauschenberg returning to his studio in his Volkswagen Bug convertible after a run to the Gulf Iron and Metal Junkyard, a source of materials for his Kabal American Zephyr series, Captiva, Florida, 1982. Photo: Unattributed

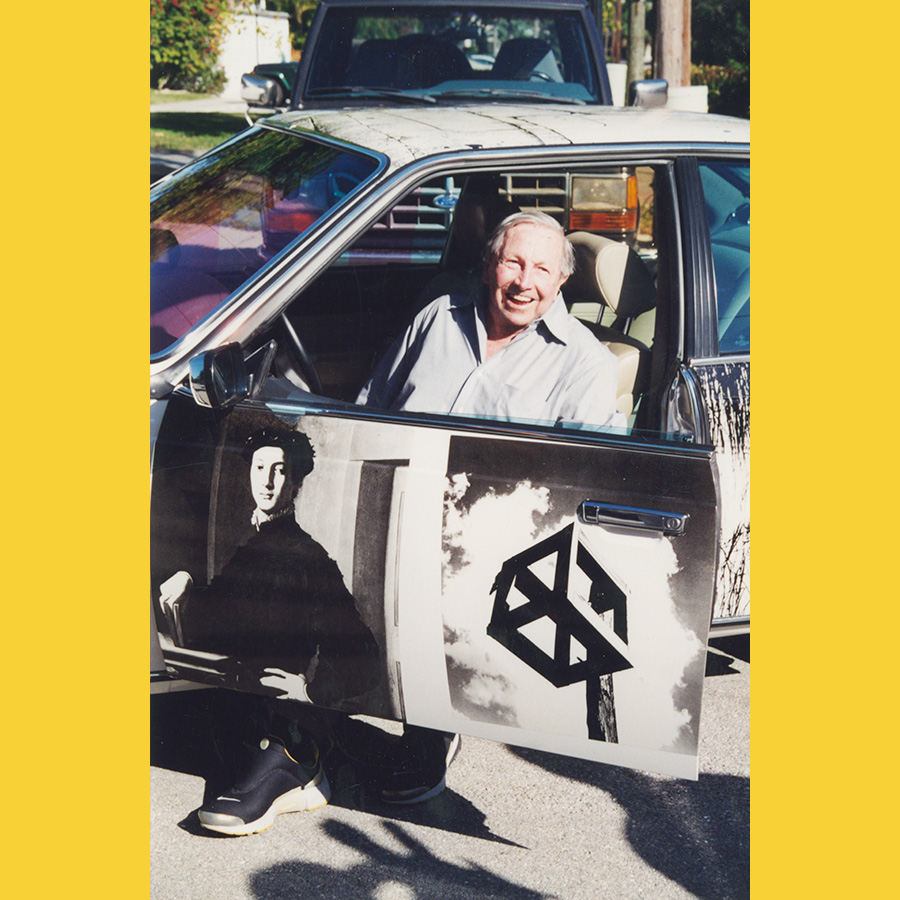

Rauschenberg with his Art Car-BMW 1986, at the exhibition Robert Rauschenberg: Beamers Eckert Fine Art, Naples, Florida, 2002

Untitled (Gold Painting) 1955 © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

Allan Kaprow, Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns Untitled [Remnant from 18 Happenings in 6 Parts] 1959 © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

Black Market 1961 © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

Scanning 1963 © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

Cat Paws 1974 © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

N.Y. Bir Calls for Öyvind Fahlström 1965 © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

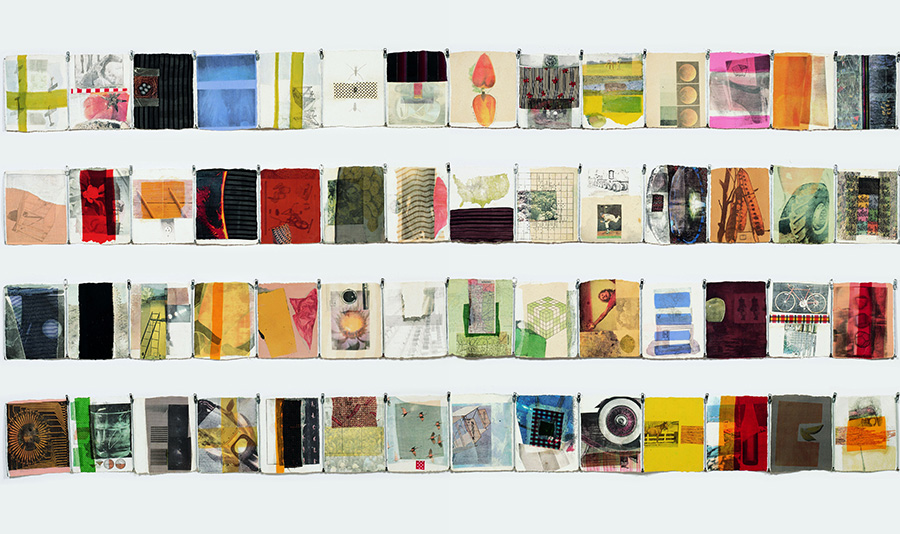

Hiccups (detail) 1978 © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

Untitled (Spread) 1983 © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

Stop Side Early Winter Glut 1987 © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

Poster for ROCI USSR 1989 © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

Triathlon (Scenario) 2005 © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

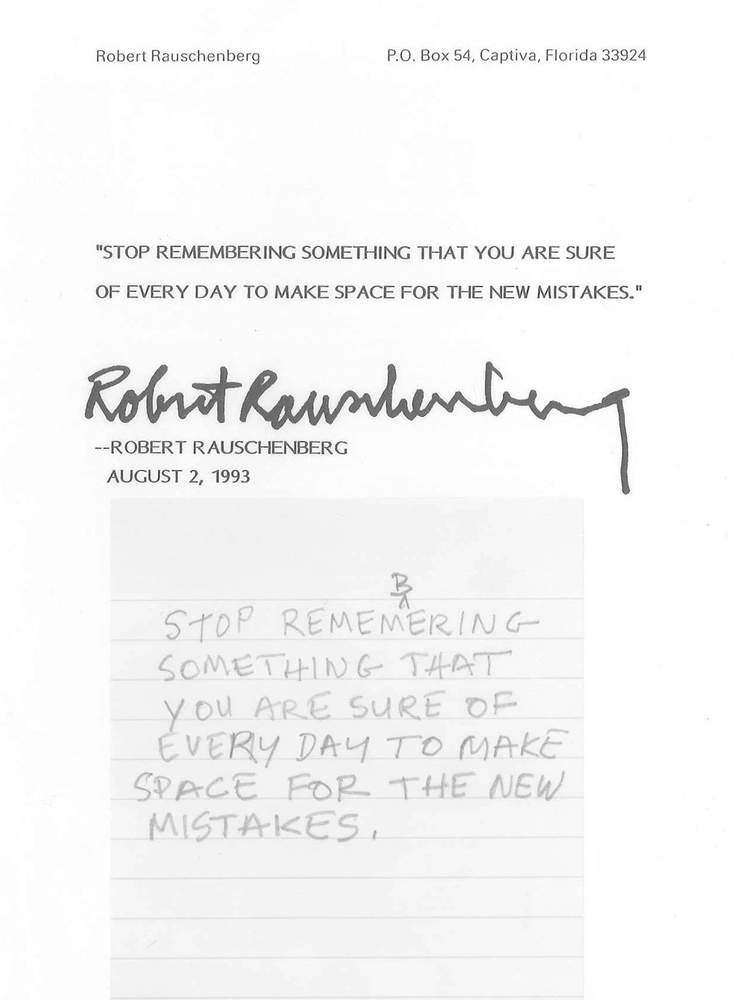

Rauschenberg’s handwritten draft of a quote for Esquire magazine, 2 August 1993.

Courtesy Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

Further Reading

- Performance Art 101: The Black Mountain College, John Cage & Merce Cunningham

- Performance Art 101: Painting and Performance

- Performance Art 101: Dance Magic Dance

- Pop art glossary term

- Abstract expressionism glossary term

- Postmodernism glossary term

- Robert Rauschenberg Tate Artist Page

- Robert Rauschenberg Foundation Overview

- Robert Rauschenberg Foundation Chronology

- Robert Rauschenberg Foundation Archives

- Rauschenberg Research Project at SFMOMA

Credits and acknowledgements

Words & Storyboard: Kirstie Beaven & Lily Bonesso

Digital design: Mark Hume

Tate Digital production team: Jen Aarvold, Kirstie Beaven, Lily Bonesso, Lucy Noakes, Saskia Mercuri, Hilary Knight

With thanks to Kayla Jenkins and Shanna Kudowitz at Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

All archival photographs and original writings Courtesy Robert Rauschenberg Foundation. Full details for all artworks can be found at Robert Rauschenberg Foundation Art & Archives