Fig.1

Dust jacket of Sunrise in the West (1926)

After first commissioning a book by Adrian Stokes (fig.1) in April 1930, the publishing house Faber & Faber produced all his subsequent books until, twenty-four years later, they rejected Michelangelo as too psychoanalytic. Yet his psychoanalytic treatment by Melanie Klein, beginning at the start of 1930, had contributed to his developing an innovative carving aesthetic through which he became acknowledged by the art historian Alan Bowness (later a director of the Tate Gallery) as possibly Britain’s ‘most original and creative’ art writer.1 To demonstrate the contribution of Stokes’s psychoanalytic treatment to this achievement I begin with its precursors in what I shall call his inside-out externalisation philosophy. I then recount the early years of his treatment using his writings, some of which are in the Tate Archive, together with writings by Klein, including her account of Stokes as two different patients, ‘Mr B’ and ‘C’. Lastly, I discuss his carving aesthetic and the ways it contributed to changes in modern art in Britain in the 1930s.

Precursors

Born in London on 27 October 1902, Stokes wrote of learning early to cope with loss by looking to the world around him. It became a means of getting away from the ‘endless succession’ of his trivial preoccupations – ‘lighting a pipe … saying good morning … watching somebody’s face … cleaning one’s teeth … deciding to take an umbrella out instead of a stick … welcoming a wild wind on the downs’ – which bothered him as a philosophy student at Oxford.2

‘I have been driven from pillar to post so that I cannot come to an understanding with the definite or even with the indefinite … All of you, in varying degrees, are being driven from pillar to post in this world of intertwining tremendosities’, he announced in his first book The Thread of Ariadne, in which he incorporated excerpts from his post-Oxford round-the-world travel diary. Rather than being driven from pillar to post by the received opinions of his parents’ generation he advocated the attitude of Christ, depicted by the Renaissance painter, Bernardino Luini, looking in ‘the distance far beyond the words He speaks and the argument He is upholding’ in the painting Christ among the Doctors (National Gallery, London). He also praised the modern ‘art of suggestion’ as a means of ‘getting behind words’.3

‘I live alone – absolutely and don’t speak to anybody and all day silly words like “grist” and “Christostums” run in my head’, he complained while beginning work on his next book Sunrise in the West.4 He found a solution in the avant-garde creations of the Ballets Russes: ‘As we stand behind the dress circle at the ballet, for once in a way we live with double intensity our own existence, and our attention is absorbed rather than shoved and jostled on some path’.5 To this he added praise of what he regarded as the forebears of modern art in the outward-looking vision of artists in early Renaissance – quattrocento – Italy. For the cover of his book Sunrise in the West (fig.2) he chose a copy of a low relief of the Roman goddess Diana in the quattrocento Tempio in Rimini.

Fig.2

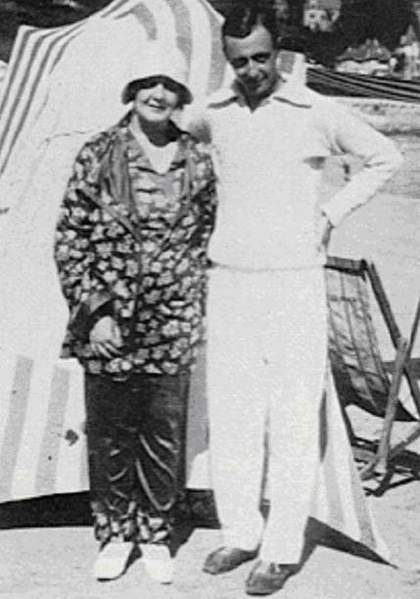

Adrian Stokes in a studio portrait of the mid-1930s

© Estate of Adrian Stokes

After this book’s publication in 1926 he was still bothered by the flow of his ideas. ‘Why do I have fear now and appetite later? What ever I feel, even if poignantly, I can suggest to myself that I might be feeling something else more worthy to be felt’, he wrote. The answer, he decided, lay in the drive of the human spirit to externalise itself, thus putting a stop to ‘destructive intellectual activities, inspired by fear, strangling … every normal response, enjoyment and expression’. 6

He praised in these externalising or inside-out terms the warlord Sigismondo Malatesta at whose command the Tempio was first created. He described Sigismondo as ‘the archetype of Humanism’ in manifesting his spirit outwardly in the form of the Tempio, a monument to his love for his mistress Isotta.7 Stokes likewise praised the sculptor Agostino di Duccio for externalising ‘the magic’ exerted by Isotta over Sigismondo in the form of ‘the moon-influence’ of Diana in the above illustrated low relief of her in the Tempio.8

After reading this, Stokes’s mentor and close friend Ezra Pound was so impressed he declared Stokes, together with himself, James Joyce, T.S. Eliot, and Wyndham Lewis, as ‘the only writers of the day’.9 In the following year, 1929, however, Stokes’s writing was brought to a standstill by inner ‘torment’.10 Through a friend’s psychoanalyst, Ernest Jones, he was referred to Melanie Klein (fig.3) and his psychoanalytic treatment began with her in early January 1930.

Fig.3

Melanie Klein and her son Hans in Brittany, summer 1930

© Melanie Klein Trust

Treatment

The previous spring Klein had presented a paper about art and psychoanalysis in which she described a Scandinavian artist, Ruth Kjär, as inspired by her inner emptiness to paint pictures of maternal figures as destroyed and made whole again.11 Influenced, perhaps, by similar interpretations of his own psychology during the first weeks of his treatment, Stokes began an essay in which he quoted approvingly Giorgione’s praise of the capacity of painting to bring together as a whole ‘all the aspects that a man can present’ in ‘a single glance’.12 It was this essay that won Stokes his first commission from Faber & Faber.

Meanwhile his work was in the doldrums when, in the 1930 summer break in his treatment, he suffered from panic following an operation (to repair schoolboy boxing damage to his nose). Attributing this panic to conflict between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ aspects of his mother in his ‘super-ego’, about which he had learnt from Klein, he hoped that further psychoanalysis would help pin down and define this agent in his mind and thus reduce its ‘terrible force’ and ‘inhuman cruelty’.13

Klein located the source of these aspects of Stokes’s super-ego in infantile rage at his mother bottle, rather than breast-feeding him as a baby. In his rage, she said, he imagined beating her breast to bits. He also imagined attacking her with his urine. Hence, said Klein, his fantasy of himself as a child urinating in Hyde Park (near his childhood home) while his mother watched from on top of a building. Hence too, Klein added, his equation of the park itself with his mother’s body as ‘hopeless, dead, dreary’ due to her ‘suspicion always of dirt’.14

As for the troubling endless-seeming ‘flow’ of words and preoccupations in his mind, Klein interpreted this as rooted in infantile fantasies about the flow of his faeces.15 She also interpreted his hatred of the black stockings he wore as an eight-year-old child as symbolising his faeces and the damage he imagined done by them to his parents’ home in making it ‘gloomy’.16 She also identified in Stokes’s comments fantasies of his father attacking his mother in their sexual intercourse with faeces, equated with the penis, and an infantile masturbation fantasy in Stokes of himself attacking their intercourse.

He dreaded his mother retaliating against his attacks on her body and on her sexual coupling with his father. Transferring this dread onto Klein, he imagined her as the child-eating witch in the story of Hansel and Gretel; as the tramps in Hyde Park who watched him eat there as a child as though they were ‘avenging mothers from whom stuff is taken’; and as a black horse in one of his dreams taking revenge on those who had been ‘accidentally kicked’ and left ‘maimed and close to death’.17 Dreading women’s revenge for his actual or imagined attacks on them, he was fearful of their bodies as though their ‘sticking out’ breasts and buttocks were means by which they might institute this revenge.18

As an infant, said Klein, he had evidently defended against fear of his mother retaliating against his rage and attacks on her ‘soft’ body for not breast-feeding him by finding a substitute in the ‘hard’ teat of his feeding bottle. He also found a substitute in the penis as ‘strong, life-giving, straight’ after being initiated into penis-sucking fellatio as a toddler by his then three- or four-year-old brother, Geoffrey.19

Klein adduced this as a factor contributing to Stokes’s homosexual affairs after leaving his public school, Rugby. She interpreted these affairs as defensive means of getting away from his inwardly occurring fear of women’s bodies as the site of oral, urinary, fecal, and penile attack and retaliation. ‘To him, only the male, in whom all was manifest and clearly visible and who concealed no secrets within himself, was the natural and beautiful object’, she observed.20 Hence, arguably, his praise of Sigismondo Malatesta making himself manifest and clearly visible in the form of the Tempio ‘pent-up to instant manifestation of all of it all at once … like mountains in unbroken sunlight’.21

Previously Klein had written about boys defending themselves against the fear and dread of their mothers’ retaliating attack on their sexuality by looking for reassurance in their penis being intact, emphasising their ‘masculine’ superiority and expressing ‘excessive aggression’.22 Now, during her psychoanalytic treatment of Stokes, she interpreted in similar terms his combatting of his inner fears and anxiety with looking at the penises of men at the swimming pool he frequented at Regent’s Street Polytechnic in London, and with masculine sadism and aggression.

This included getting away from fear of the cruelty of his super-ego through sadistic sex with men he experienced as feminine objects of his aggression. Cowardice, said Klein, led him to choose as its objects men who were weaker than him and men like his brother, Geoffrey, who were masochistic, since he thereby felt less guilty about the suffering his sadism inflicted on them. He was nevertheless fearful lest his dress (his evening dress tie, for instance) betray his inferiority, and lest his inner conflict between sadism and guilt show on his face as sinister and mad. As a result, despite being remarkably good-looking, he was afraid others found his physical appearance repulsive.

He felt less conflict between sadism and guilt in sexual affairs with men who trusted him and made little of his sadism. With such men, or at least with men like his adored eldest brother, Philip, he fell deeply in love. With other men his use of his penis as instrument of his sadism left him sexually unsatisfied. As for women, he only had sexual intercourse with them ‘once or twice’ and then only from curiosity, wanting to do what other men did, and so as not to upset the woman involved, who was more eager to have sex with him than he was with her.23

He had little confidence in being able to repair the damage done by his imagined or actual attacks on others. He could not bear his impotence in this respect in sex with women. The failure of his attempts to repair the damage done by his sadism to his brother, Geoffrey, by attempting to help him recover from his post-war physical ills was the immediate cause, said Klein, of the breakdown bringing Stokes into psychoanalytic treatment. But he found its formality, lack of contact, and Klein being a Jew difficult. He was ‘pleased about’ being connected through his mother to the once famous financier, philanthropist, and Sheriff of London, Sir Moses Montefiore, ‘but not about being Jewish’.24 He also disliked ‘Jewish formality, emptiness and suspicion, nothing given, jealous pride’ against which, he said, he had sought to develop his capacity for ‘intimacy’.25

He valued being able to talk about this in his psychoanalytic treatment with Klein. He also valued this treatment for attending to inner destructiveness as cause of what he described as an ‘overplus of anxiety’.26 As he increasingly internalised his analysis with Klein as beneficial – she put it in terms of his analysis enabling him to identify with femininity – he felt more confident about having the wherewithal to resume work in spring 1931 on his book The Quattro Cento.

Klein likened this work to his countering an image of his mother’s body and London as ‘dark, lifeless and ruined’ by imagining ‘a city full of life, light and beauty’. His work on this book had the same meaning for him as this city, said Klein, in that, in writing it, he brought together ‘each separate bit of information, each single sentence’ so that the book represented himself and his mother as ‘restored’ and whole.27 Stokes might well have had this in mind in concluding The Quattro Cento with praise of the quattrocento courtyard of the ducal palace in Urbino for bringing together rough brick and smooth marble pilasters: ‘Ones each as single as the Whole’. He likened its unifying effect in this respect to paintings by Piero della Francesca conveying a sense of wholeness even when they depict ‘a battle in progress’ (a detail of which he included on the cover of The Quattro Cento; fig.4).28

Fig.4

Dust jacket of The Quattro Cento (1932), with detail from The Victory of Heraclius over Chosroes by Piero della Francesca

‘Now I suppose I must do the Malatesta volume’, he told Ezra Pound on sending him a copy of The Quattro Cento when it was first produced in May 1932.29 He went to Sigismondo Malatesta’s library in Cesena and to his Tempio in Rimini that summer. With him he took his newly acquired girlfriend, a young sculptress named Mollie Higgins to whom he dedicated The Quattro Cento’s sequel, Stones of Rimini. But he did not devote this to Sigismondo Malatesta as he had previously planned, in order to illustrate the latter’s philosophy of life and art expressing the drive of the human spirit to externalise itself inside-out. Instead, in Stones of Rimini he transformed this philosophy into an emphasis upon the outward physical material of art inspiring its creation.

While writing Stones of Rimini, he published a review of a book by Melanie Klein in which he praised psychoanalysts for attending to the impact of their outward physical presence in evoking ‘the feel of early situations’ in their patients.30 In his case this included Klein attending to the impact of her physical presence in evoking fear in Stokes of her being fatally injured in a traffic accident. This in turn evoked his childhood fear, when crossing the Bayswater Road with his nursemaid, that he might never see his mother again. Klein’s physical presence also evoked in him a paranoid dream about his mother failing to recognise that frying something alive was torture. Her presence and his dislike of the way she lit her cigarette also brought to mind his contempt for his father serving ‘balls the wrong way at tennis’.31

Klein cited these examples of paranoia and contempt as defences against facing and being concerned about the destruction done to love by hate, expressed through his contemptuously dominating over others or becoming fearful of their domination and persecution. This, in turn, arguably contributed to Stokes revising his previous inside-out account of life and of art as expressing the drive of the human spirit to externalise itself. Instead, he now argued that, far from art expressing this inwardly given drive in the form of artists dominating and modeling their material to realise their preconceived fantasies and ideas, art should result from artists responding to what the outward physical material of their art inwardly suggests. Herein resided his carving aesthetic which he first explained in print in an article published by T.S. Eliot in the October 1933 issue of the Criterion.

Carving

‘People touch things according to their shape. A single shape is made magnificent by perennial touching. For the hand explores, all unconsciously to reveal, to magnify an existent form’, Stokes wrote in this article. ‘And just as the cultivator works the surface of the Mother Earth, so the sculptor rubs his stone to elicit the shapes that his eye has sown in the matrix’, he continued. ‘Whatever its plastic value, a figure carved in stone is fine carving when one feels that not the figure, but the stone through the medium of the figure, has come to life’, he went on. ‘The communion with a material, the mode of eliciting the plastic shape, are the essence of carving.’ He likened it to ‘the definition that our hands and mouths bestow on those we love’ and described it as articulating ‘something that already exists’ in the physical material of the artist’s work.32

He promoted in these terms paintings by Ben Nicholson, shown together with sculpture by Barbara Hepworth, at an autumn 1933 exhibition at the Lefevre Galleries in London. In reviewing this exhibition in the Spectator he wrote: ‘Just as the carver consults the stone for the reinforcement of his idea, so Mr Nicholson has started to paint when he prepares his canvases. It is obvious that he relies more than is usual upon their rich plaster covering or some other interesting surface to guide him.’33 He likewise praised in terms of his new carving aesthetic collages by Nicholson and his design of the exhibition catalogue and invitation cards for elucidating with circles the plane on which they lie. Arguably influenced by this, Nicholson created in December 1933 the first of his abstract geometrical low relief paintings for which he later became famed as one of Britain’s leading twentieth-century artists. He also ‘elucidated with circles the plane on which they lie’ when designing the cover of Stones of Rimini in which Stokes first detailed his carving aesthetic at length (fig.5).

Fig.5

Dust jacket of Stones of Rimini (1934) designed by Ben Nicholson

By the time this book was published, in January 1934, Stokes had used his carving aesthetic to promote Barbara Hepworth’s contribution to a revolution in modern sculpture in Britain which rejected representational or romantic, fantasy-led art in favour of abstraction. Mindful, perhaps, of Klein’s attention to mothering during his continuing psychoanalytic treatment, Stokes singled out for particular praise Hepworth’s 1933 abstract alabaster sculpture Composition, of which he said:

The stone is beautifully rubbed: it is continuous as an enlarging snowball on the run; yet part of the matrix is detached as a subtly flattened pebble. This is the child which the mother owns with all her weight, a child that is of the block yet separate, beyond her womb yet of her being … It is not a matter of a mother and child group represented in stone. Miss Hepworth’s stone is a mother, her huge pebble its child.34

He also helped Hepworth write her contribution to the modern art book Unit 1. Adopting his carving aesthetic, she wrote that, in creating abstract sculpture, she sought to achieve ‘a perfect relationship between the mind and the colour, light and weight which is the stone, made by the hand which feels.’35

Meanwhile, Stokes had promoted in terms of his carving aesthetic the modern art of Henry Moore. In a review in the Spectator of an exhibition of Moore’s sculpture at the Leicester Galleries in London, Stokes particularly admired an abstract composition carved by Moore in African Wonderstone to display ‘a silvery light and … swift convergences … as a solid cream upon the surface of his stone … wide shallow and smooth’.36 Moore, in turn, wrote about his work in terms of this self-same carving aesthetic in emphasising the importance of the ‘direct’ work of sculptors with the ‘material’ of their art so it can guide them in creating it.37

That year also saw Stokes promote the avant-garde creations of the Ballets Russes in terms of his carving aesthetic. In his book To-Night the Ballet, published in June 1934, he praised the carving, as it were, of these creations from music, street theatre, the commedia dell’arte, and classical ballet, and he likened dancers shaping the space of the stage to sculptors shaping stone. Then, in Russian Ballets, he countered criticism of the dancer-choreographer Léonide Massine’s abstract ballet Les Présages of 1933 with praise of his carving from its music a Kleinian ‘good object’ in the form of its principal dancers, Irina Baranova and David Lichine. 38

After ending his psychoanalytic treatment with Klein in 1935, Stokes further developed his carving aesthetic in terms of the responsiveness of painters to colour in the world around them as a means of realising the otherwise overly abstract modern art doctrine of ‘significant form’.39 From his psychoanalytic treatment he had learnt about the psychological cost to himself of externalising his inwardly occurring fantasies (in, for instance, sadistically dominating others, not least in sex). This doubtless contributed to his implicitly rejecting the ‘phantasy’-based romantic version of art espoused by Freud.40 It also arguably contributed to his explicit rejection of the unconscious-led painting which surrealists sought to achieve, to the neglect, he wrote, that art, like the inner life of the mind, finds itself in ‘the organisation of the outside world’.41

‘Colour is something “out there”’ tingeing objects ‘as does the life-blood our skins,’ he insisted. The ‘true colourist’ thus recreates by ‘his use of colour the “other”, “out-there” vitality he attributes to the surface of the canvas, just as the carver reveals the potential life of the stone’. Or, as Stokes also put it in his book Colour & Form: ‘The colours of a picture are fine when one feels that not the colours but each and every form through the medium of their colours has come to an equal fruition. Thus is carving conception realized in painting’.42

Klein had emphasised the bringing together of good and bad, loved and hated, images of others in the ego or super-ego. Now Stokes emphasised the bringing together of forms through colour in extending his carving aesthetic to painting. He praised in terms of this aesthetic Picasso’s painting, Woman with a Mandolin 1925 and its effect in achieving what Stokes described as ‘the wished-for stabilising’ of ‘miscellaneous mixed-up archetypal figures within us, absorbed in childhood, that are by no means at peace among themselves.’43 He likewise praised Ben Nicholson’s abstract paintings – 1934–6, for instance – for visually unifying parts as a whole via colour so that, as Stokes put it, ‘basic fantasies of inner disorder find their calm and come to be identified with an objective harmony’.44

‘The painter of a modeling proclivity recharges the landscape with shape. The painter of a carving proclivity is at pains to show that the forms there each have a face which he discloses’, the artist Graham Bell, quoted approvingly from Stokes’s book Colour & Form in reviewing it in the New Statesman.45 By the time this review was published in October 1937 Stokes’s carving aesthetic had begun influencing a new British art movement, described by William Coldstream as ‘Objective Realism’.46 Together with Bell and other artists, Coldstream furthered this movement in founding what became known as the Euston Road school of drawing and painting where Stokes became a student in 1937, married a fellow student, Margaret Mellis, the following July, and moved with her in April 1939 to live near St Ives in Cornwall.

In the following years Stokes’s carving aesthetic influenced Peter Lanyon and other young artists in St Ives where, during the Second World War, Stokes became a catalyst of the town’s transformation into an internationally acclaimed centre of modern art.47 He further developed his carving aesthetic, together with psychoanalysis, in developing insights in his subsequent Faber & Faber published books about ways the outside physical world gives form to otherwise more or less formless inwardly occurring fantasy and imagination. This, in turn, led to his book, Michelangelo, with which I began. My concern here, however, has been to highlight ways his psychoanalytic treatment contributed to his transforming his early inside-out externalisation philosophy into a carving aesthetic and his use of this in helping to promote and bring about major changes in modern art in Britain in the 1930s.

Acknowledgements

My thanks to Paul Tucker for his help in transcribing and interpreting writings by Stokes; to Martin Golding and Clare Ungerson for their detailed comments on an earlier version of this paper; to those working in the Tate Archive and the archives of University College, London, the Berg collection in the New York Public Library and in the Beinecke collection in Yale; to Markie Robson-Scott for copies of letters from Stokes to her father, William Robson-Scott; to Philip Stokes for scans of book covers reproduced in this article; and to Ian Angus and Telfer Stokes, as well as to Richard Rusbridger, Hon Secretary of the Melanie Klein Trust, for kindly granting permission for the inclusion here of copyright material. A version of this paper was presented at the workshop devoted to Adrian Stokes as part of the Tate’s Art Writers in Britain series on 24 May 2013, organised by Paul Tucker.