Cleaning

The start of the process of removing discoloured varnish from this painting is described in part 1 of this project. Most of the painting was cleaned in this straightforward way, and the appearance of dark areas was much improved after varnish removal, figs 1 and 2.

Fig 1. Detail of Portia’s robe showing the true light grey colour of the paint, this appeared green when below the discoloured varnish.

Fig 2. Detail of Portia’s papers during varnish removal.

Problem areas

Several areas however did not respond to the solvent mixture in a satisfactory way. The paint in the brown foreground, the red rug at the left and the red curtain at the right all proved sensitive to the solvent, so that removing the varnish layer would have risked removing pigment. To prevent this from happening, the varnish in these areas was thinned as much as possible and then cleaning was stopped just before contact with the paint surface.

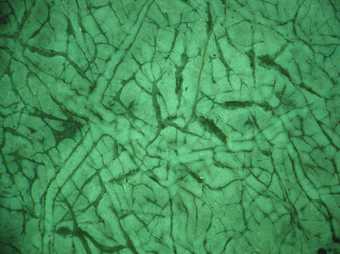

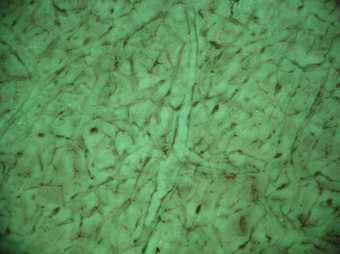

In these problem areas, the paint surface had an unusual appearance. Under the microscope we could see that cupped and ragged drying cracks had formed in the paint, often revealing a brown layer below, and the crack edges would sometimes break the surface of the varnish. This contrasted with the paint observed everywhere else, which was flat and opaque and criss-crossed with sharp edged age cracks. It may be that a resin has been added to the oil medium of the paint in these problem passages and it is possible that they were painted by a different hand, finishing off areas which Zoffany had left incomplete. The retouching in these areas suggests that the sensitive paint might have been damaged during past cleaning and then overpainted to hide abrasions.

Johan Zoffany

Charles Macklin as Shylock circa 1768, paintwork detail

Johan Zoffany

Charles Macklin as Shylock circa 1768, detail of paintwork

Johan Zoffany

Charles Macklin as Shylock circa 1768, detail of paintwork

Fig 3 a b and c [above] Detail of the paint at the foreground of the painting, in normal, raking and ultraviolet light. The images show the raised crack pattern and the crack edges breaking through the varnish, which fluoresces a green colour under UV light.

Johan Zoffany

Charles Macklin as Shylock circa 1768, detail of paintwork

Johan Zoffany

Charles Macklin as Shylock circa 1768, detail of paintwork

Fig 4 a and b [above] Detail of the paint of the red curtain.

Fig 5 Detail of the figure of the Duke with the former figure visible beneath, especially the hat which is in the lap of the upper figure.

The strange appearance of the paint is possibly connected to the reforming process, see part 1 – strong, slow-evaporating solvents may have been absorbed into the paint layer through the varnish, softening the paint medium and allowing layers to merge. In the central area of the painting, the milky appearance of the paint may be due to this merging of layers, particularly around the figure of the Duke where an earlier position of the same figure now shows through the upper layers of paint applied to obliterate it.

Another two specific passages of paint which proved impossible to clean fully were Lord Mansfield’s chair and Bassanio’s red jacket. In both cases the paint looks incongruous – glossier and more transparent than the surrounding paint which is matt and rather chalky. It is possible that these details were added by another hand to the unfinished painting to make it look more complete and therefore more saleable. The chair is crude in appearance and does not integrate properly with the Mansfield figure, with a margin left at the junction, fig 6. Bassanio’s red coat is also crudely painted. A sample of paint was taken from the coat to investigate the layer structure, but there was no certain evidence to indicate that the coat had been added later or by a different artist. Therefore it had to remain and was retouched to try to improve its appearance and integration into the surrounding scene.

Fig 6 Detail of the chair, showing the incongruous junction between the chair and the figure and the crude nature of the paint.

Fig 7 Detail of Bassanio’s coat

Old retouchings

Discoloured and inaccurately applied old retouchings could often easily be removed along with the varnish. In other areas of the painting, less soluble overpaint had to be removed mechanically with a scalpel blade fig 10.

There were large areas of overpaint in the top right quadrant of the background, covering small abrasions in the original paint below and one larger damage: the site of an old repaired tear in the canvas, fig 8 and 9. The original paint below these retouchings was found to be in better condition than the surrounding paint, perhaps as the overpaint had shielded it from the worst effects of the reforming solvents.

Fig 8. Detail of the background at the top right of the painting, showing warm brown overpaint concealing small damages and an old repaired tear in the canvas.

Fig 9. The tear with most of the overpaint removed. The white material is chalk putty filler. The area previously covered by overpaint is noticeably less cracked and more saturated than the surrounding paint.

Fig 10. Detail of Antonio’s face and neck showing small strokes of darkened and discoloured overpaint applied to disguise cracks in the paint.

Completion of treatment

To complete the treatment, paint losses were filled with putty and inpainted to match the surrounding paint. This was carried out using loose pigments bound in MS2A, a synthetic resin developed for use as a conservation varnish. Final varnishing took the form of many coats of MS2A synthetic resin varnish and Paraloid B72 synthetic resin varnish, applied with a spray-gun to produce an even gloss over the surface of the painting.

Fig 11 The painting after treatment.

Technical examination

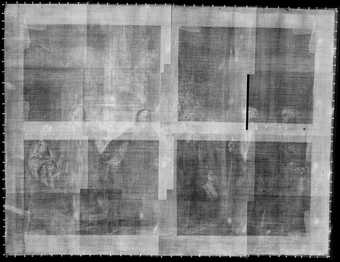

Pentimenti are visible with the naked eye: the former position of the Duke and a former position of the stage curtain. The latter disrupts the statue and plinth, which seem to be last minute additions to the scene. Raised lines of paint texture in the background at the top left and running through the plinth are explained by an X-ray image of the painting which shows a stage backdrop with classical architecture, including a triangular pediment. Zoffany completely obliterated this with the blank background paint we see today.

The X-ray also shows brush marks which suggest a sketchy figure exists below the red coat of Bassanio. If that figure was left in a very vestigial state by Zoffany then that could be a reason for the addition of the red coat at a later date.

Fig 12 X radiograph of the painting

Close observation of the brush strokes under the microscope may be able to throw some light on a conundrum regarding the history of the painting. Zoffany has painted Act IV scene I of an actual production of The Merchant of Venice starring Macklin which ran from 1768-9 at the Covent Garden theatre. In 1775 Macklin pursued a lawsuit against some critics who had sabotaged some of his performances by heckling. Lord Chief Justice Mansfield and Richard, Lord Aston, were the presiding judges at the trial and they found in favour of the actor. The inclusion of the figure of Mansfield at the extreme left of this scene (and it is thought that the figure to the left of Shylock could be Lord Aston) may be a reference to this trial, despite it having taken place 6 years after the performance. Close inspection of the paint layers does indeed show that the figures of Mansfield and Aston were added after Shylock had been painted, supporting a theory that Zoffany started work on the composition when the play began and came back to the painting later on, after the trial. We do not know why it was not finished: perhaps taste had moved on in the intervening years while Zoffany was in India, and the theatrical conservation piece with which Zoffany made his name was no longer in fashion.