Fig.1

Sir Godfrey Kneller 1643‒1723

Philip, 4th Lord of Wharton 1685

Oil paint on canvas

2286 x 1448 mm

T12029

Fig.2

Philip, 4th Lord of Wharton shown in raking light from the left

The painting (fig.1) is on a single piece of plain woven, coarse linen canvas, which has been lined with glue paste, and attached with coated steel tacks to a late twentieth-century stretcher.1 The original tacking margins are mostly intact, though the original tack holes now form part of the picture surface on the extreme top, bottom and right edges. There is faint cusping on all sides of the original canvas. The support has no planar distortions, but, as raking light (fig.2) shows, it has been stretched on a slight diagonal.

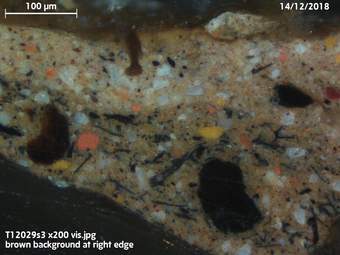

Fig.3

Cross-section from the left edge at the tacking margin, showing the brown floor colour as a single layer of paint applied over the priming and ground

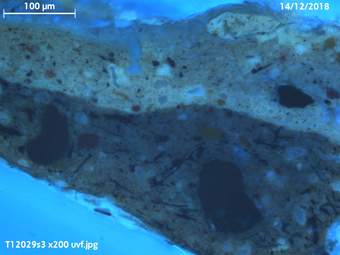

Fig.4

The same cross-section seen in ultraviolet light. Three varnishes of natural resin type, the lower two with a significant amount of dirt on top can be seen, but not the recently applied synthetic varnish. At the base of the section some lining adhesive can be recognised by its bright white fluorescence.

Fig.5

Cross-section from the right edge at the tacking margin, showing the brown background to the right of the crown

Fig.6

The same cross-section seen in ultraviolet light. The varnish has flowed into the paint through surface cracks, at the base of the section some lining adhesive can be recognised by its bright white fluorescence

The ground (figs.3‒6) is a warm mid grey, made from many large particles of charcoal and a few large particles of Vandyke brown, in fine yellow ochre and lead white, with some red lead, in oil medium. The red lead is present as rounded aggregates, and since very many lead soap aggregates are present too, formed from a chemical reaction between lead white and the oil medium, the red lead has likely developed over time from some of them. This makes the ground warmer in tone than it once was. The tan coloured priming applied on top includes a greater proportion of lead white and less yellow ochre, with a lesser amount of charcoal and some very fine-grained bone black, in oil medium. It too includes many lead soap aggregates, and a few of them have turned into red lead aggregates. The ground and priming together are far thicker than the paint layers, which are few and individually thin.

No underdrawing is evident to the eye or by infrared photography, but the figure appears to have been laid in with broad lines of brushed brown paint, left visible to form the darkest shadows of the face and hands.

The paint is thin, applied in the background as a single layer, but dense and opaque. The medium is likely to be unmodified oil. The brown background (figs.3 and 4) includes yellow ochre and fine-grained bone black, while the floor (figs.5 and 6) is painted a dark grey which includes fine bone black and lead white with some yellow ochre and a very little vermilion. All the paint is lean in consistency and was applied on the figure with stiff brushes and vigorous strokes descriptive of the form.

Structurally the painting is sound, but it is evident that there were areas of lifting paint in the red skirt before the lining, and a network of age cracks extends all over the surface. A tear about 80 mm long has been mended in the tablecloth beneath the crown, 100 mm in from the right edge. Now a patch of very discoloured overpaint obscures the mended tear and surrounding areas of original paint. There is modern retouching on the lines delineating the figure and his robes. The background includes fillings and drip-marks of blanched varnish, and is pocked at random with tiny losses of paint scattered across the background, where lead soap aggregates have protruded through. The surface has been overcleaned in several areas, notably the blue tablecloth beneath the crown, in parts of the background and in the shoes, which has ‘topped’ the protruding lead soap aggregates to create the tiny losses of paint. Parts of the background, the tablecloth and the signature have blanched as a result of the harsh cleaning. There is evidence from surface examination with the microscope that at least parts of the red robe were glazed with a lake pigment, now largely faded or overcleaned.

At acquisition there was a thin, patchy varnish, probably of synthetic type on the surface. It remains in place, while a new varnish of synthetic resin (MS2A polycyclohexanone resin) was applied prior to minor retouches in the same resin, and a final application of the same varnish by spraying.

The frame is in the ‘Kent’ style of the 1720s to 1760s, carved and gilded, and therefore it post-dates the painting, and from its construction might date as late as the early 1800s. This ‘architectural’ frame type was generally used round many paintings, within a decorative scheme, possibly applied to paintings acquired successively. Interestingly, the top two rosettes are different from the lower two, yet the gilding schemes and carved ‘style’ appear to be similar for all the rosettes: perhaps this was a purposeful design rather than a replacement. The gilding scheme includes both oil gilding and water gilding, and is likely to be the original finish.

January 2019