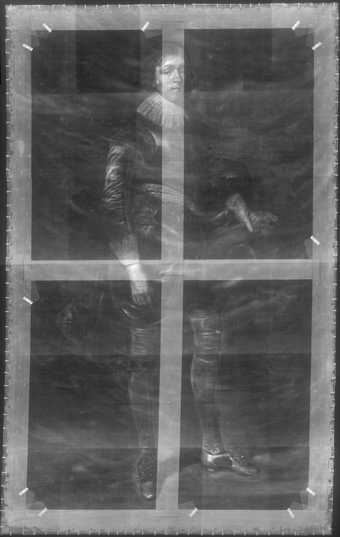

Fig.1

Daniel Mytens the Elder c.1590−c.1647

Portrait of James Hamilton, Earl of Arran, Later 3rd Marquis and 1st Duke of Hamilton, Aged 17

1623

Oil paint on canvas

2055 x 1295 mm

N03474

This painting is in oil on canvas measuring 2055 x 1295 mm (fig.1). The support is a single piece of fine linen canvas with 19 vertical and 16 horizontal threads per square centimetre. The current dimensions of the painting date from 1975 when the painting was relined at Tate and was given a new stretcher to accommodate as much of the painted design as possible. Before that treatment took place, the painting, lined with a starch based adhesive, was mounted on a much smaller stretcher, which had necessitated the folding back of original painted canvas behind its bars. The tack holes relating this attachment can be seen in the X-radiograph (fig.2). From the X-radiograph it is clear also that the reason for this reduction in visible size was the amount of paint loss around the edges of the composition. Even now that the dimensions are nearer their original state, it seems likely that the painting was once bigger still. The absence of cusping at the edges of the canvas (fig.2) suggests that a small reduction in size had taken place even before the starch lining and its associated stretcher described above.1

Fig.2

X-radiograph of Portrait of James Hamilton, Earl of Arran, Later 3rd Marquis and 1st Duke of Hamilton, Aged 17 1623

The ground is tan colour, composed mostly of chalk with lead white, black and red ochre, pipeclay and kaolin bound in oil.2 The priming on top of the ground is a thin coat of opaque dark grey paint, composed of lead white with charcoal black (figs.3, 4). The tiny protrusions of lead soap-aggregates, which are noticeable at the paint surface, can be seen in the cross-sections to originate in the ground layer.3

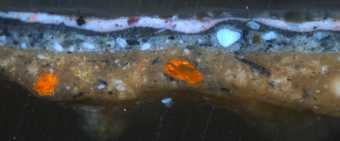

Fig.3

Cross-section through the pink strap of the left shoe, photographed at x360 magnification. From the bottom up it shows: a layer of glue size applied directly to the canvas; pale tan coloured ground layer, containing lead soap aggregates (bright orangey red); opaque grey priming; dark grey paint of the shadowed floor just lapping underneath the pink shoe; opaque pink paint of the shoe; opaque pink paint of the shoe, containing lead white, vermilion, red lake and black

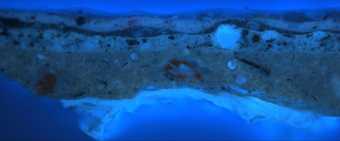

Fig.4

Cross-section through the pink strap of the left shoe, photographed at x360 magnification, viewed in ultraviolet light. From the bottom up it shows: a layer of glue size applied directly to the canvas; pale tan coloured ground layer, containing lead soap aggregates (bright red); opaque grey priming; dark grey paint of the shadowed floor just lapping underneath the pink shoe; opaque pink paint of the shoe; opaque pink paint of the shoe, containing lead white, vermilion, red lake and black

No underdrawing is detectable with surface microscopy or infrared reflectography but it is evident from the reserves left for each element of the composition and the absence of any major revisions, that the painting was carefully planned from the outset (figs.5‒7). The only detectable changes are very minor adjustments to the width of the legs at the calves, visible in the X-radiograph (fig.2).

Mytens used a limited palette of pigments: lead white, bone black, vermilion, red lake, yellow and red ochre, umber, sienna. Chalk was also used in some areas as a bulking agent, along with ground glass and pipeclay fillers. The particle size of the pigments is generally very fine. The artist’s technique was direct, applying only one or two layers of thin paint, mostly wet in wet; finally he applied glazing here and there on top to achieve depth and richness of tone (figs.8‒11).

He exploited the grey priming to act as a recessive shadow in the lace collar and cuffs (fig.12). The grey priming was also used to help model the light passages of paint, such as the white gloves and shoes, exploiting the cool tones derived from the turbid medium effect by scumbling white over grey.4 This effect has been heightened by wear and the increased transparency of paint over time. A very fine blue pigment, possibly indigo, is present in low concentrations in the sitter’s gloves. It is also present in the shadows of the sitter’s shoes. Another, equally finely ground blue pigment was used in the whites of the eyes; this appears to be an azurite-type pigment (fig.13). Yellow ochre, umber and sienna pigments were also noted in the shadows of the shoes and sword hilt.

Fig.12

Detail of the edge of the collar at x8 magnification, showing the grey priming left visible as a tone in the composition

Fig.13

Detail at x20 magnification of blue pigment in the white of the sitter’s left eye

The black costume was built up from dark to light with paint made up of bone black with admixtures of lead white, chalk, earth colours and Cologne earth. These black tones were applied mostly wet-in-wet. The highlights and details were then applied on top and the shadows reinforced with a glaze of black. This two layer sequence can be seen where the black costume meets the reserve for the sitter’s collar (fig.14). The blacks and greys of the costume are in good condition, in contrast with the blanched appearance of the background.

Fig.14

Detail at x8 of two coats of black paint in the costume next to the collar

The dark grey background paint contains bone black, lead white, chalk, umber, earth colours and glassy particles. Despite having a fairly similar composition to the black paint of the costume, except that the proportion of chalk in the costume is much lower, the background has become much paler over time. Old retouchings, which have remained unchanged, are now significantly darker than the rest of the background. The precise reason for the degradation of the background is unclear; at very high magnification its pale, crazed surface shows darker paint down the cracks (fig.15), which may indicate that it is a surface phenomenon triggered perhaps by light, as it is less pronounced in areas which have been covered up in the past. Cross-sections also suggest that the degradation is worse at the surface.

Fig.15

Detail at x12 magnification of the blanched and crazed background paint

May 2005