Fig.1

John Michael Wright 1617–1680

Portrait of Mary Villiers, Duchess of Richmond, with her late son Esme and her daughter Mary c.1661

Tate

T06455

Fig.2

X-radiograph detail of Mary Villiers’ face from Portrait of Mary Villiers, Duchess of Richmond, with her late son Esme and her daughter Mary

Fig.3

X-radiograph detail of hands from Portrait of Mary Villiers, Duchess of Richmond, with her late son Esme and her daughter Mary

Fig.4

The back of Portrait of Mary Villiers, Duchess of Richmond, with her late son Esme and her daughter Mary on acquisition, showing the early stretcher, which is either the original or contemporary with the eighteenth-century lining

This painting is in oil paint on canvas measuring 965 x 1195 mm (fig.1). The linen canvas is of medium weight and is plainly woven (figs.2–3). The canvas now has a modern lining but, when first acquired by Tate in 1991, it had an interesting lining, which conforms to a recipe known to be from the eighteenth century; the recipe is written down in Joseph Wright of Derby’s notebook.1 With this method the painting was removed from the original stretcher and placed face down on a flat board. New canvas was attached to the original stretcher or strainer (or a new replacement if the original were damaged). Paste made from flour (rye flour in Joseph Wright’s recipe) and ale was smeared over the back of the painting, after which the stretcher with the new canvas attached was inverted over the back of the painting. Pressure was applied to the back of this ensemble by rubbing it, after which the ensemble was placed face up and pressure was applied the front areas inaccessible from the back on account of the stretcher bars, again by rubbing them. Because it was too weak to continue to support the painting adequately, this early lining had to be removed after acquisition, and a modern stretcher was made. The stretcher associated with the early lining, which was either original or contemporary with the time of painting, was made of pine (fig.4).

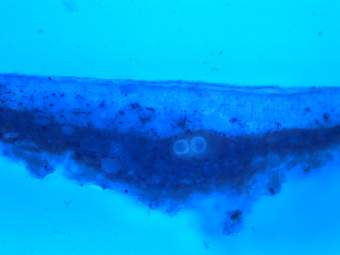

Fig.5

Cross-section though the shadowed inner cuff of Mary Villers’s sleeve, taken before varnish removal and photographed at x200 magnification. From the bottom upwards: glue size from the canvas; brick-red ground; mid-grey dead colouring; dark purplish blue paint of sleeve cuff; two layers of old varnish

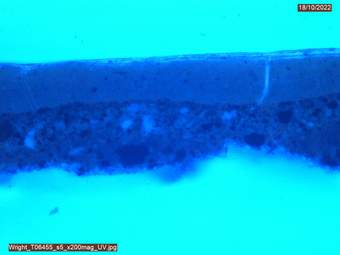

Fig.6

The same cross-section as in fig.5, photographed at x200 magnification in ultraviolet light

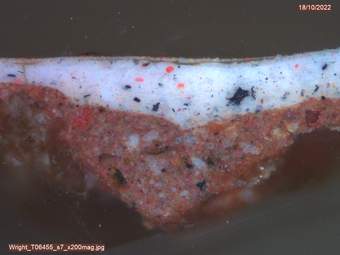

Fig.7

Cross-section through dark red paint of the ledge at the lower right edge, taken before varnish removal and photographed at x200 magnification. From the bottom upwards: brick-red ground; dark grey dead colouring; dark red underpainting of ledge; thick semi-translucent red glaze; two coats of varnish

Fig.8

The same cross-section as in fig.7, photographed at x200 magnification in ultraviolet light. The fluorescence of the red glaze indicates a resinous or oleo-resinous binding medium

Fig.9

Cross-section through a shadow in the red curtain, taken before varnish removal and photographed at x200 magnification. From the bottom upwards: glue-size from the canvas; brick-red ground; very dark grey dead colouring; opaque red underpainting; thick, semi-translucent red laze; two coats of old varnish

Fig.10

The same cross-section as in fig.9, photographed at x200 magnification in ultraviolet light. Note the fluorescence of the red glaze, indicating a resinous or oleo-resinous binding medium

Fig.11

Cross-section through Mary Villiers’s face, from the edge of an old damage. Photographed at x200 magnification. From the bottom upwards: brick-red ground; pale greyish underpaint of face; flesh colour for face; later overpaint and varnish

Fig.12

The same cross-section as in fig.11, photographed at x200 magnification in ultraviolet light

Fig.13

Infrared reflectogram of Portrait of Mary Villiers, Duchess of Richmond, with her late son Esme and her daughter Mary

The ground is brick red colour and is composed of lead white mixed with earth colours and black (fig.5).2 The painting was begun with a dead colouring to lay in the general shapes of the figure group, curtain and sky.3 It can be seen in figs.5–12, cross-section samples taken from various areas, that the tone of the dead colouring varies according to the tone of the final, visible colours. No underdrawing can be detected in the infrared reflectogram (fig.13).

Once the dead colouring was dry, the artist applied opaque, muted reds to establish the folds of the curtains and the red ledge in the foreground. Elsewhere – the flesh tones and the lilac blues of the costume – it was painted thickly with the final colours, wet-in-wet. Finally the artist applied thick red glazes to the curtains and foreground red ledge. It can be seen in the cross-sections from those areas (figs.7–10) that the glazes have a resinous or oleo-resinous binding medium, whereas the bulk of the painting appears to be in unmodified drying oil.

Fig.14

Portrait of Mary Villiers, Duchess of Richmond, with her late son Esme and her daughter Mary viewed in ultraviolet light following the 2012 treatment

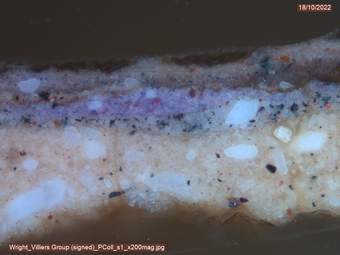

Fig.15

Cross-section from the lilac coloured dress of Mary Villiers from the original, signed and dated Portrait of Mary Villiers, Duchess of Richmond, with her late son Esme and her daughter Mary. Private collection. From the bottom upwards, pinkish beige ground; grey dead colouring; lilac coloured paint of dress; modern retouching and dark varnish. Note that the colour of the ground is different from that in the Tate’s painting.

The artist mixed the expensive blue pigment ultramarine with lead white and red lake to make the lilac blues of Mary Villiers’s costume. The red lake has mostly faded except at the very bottom edge where the paint was protected from light by the rebate of the current frame. When the painting is viewed in ultraviolet light (fig.14) it is clear that the red lake used for the costumes and the ledge is not based on madder, whereas the red lake used to glaze the red velvet chair is. This use of ultramarine is interesting because this painting is not the first, signed version of this portrait group, and there are other near identical versions too, all from Wright’s studio.4 The signed version, dated 1661, also has ultramarine in the costume, which one might expect in the prime version, but it is of note that Wright used the same expensive blue in the other versions (fig.15); his practice was of high quality.

Fig.16

The reverse of Portrait of Mary Villiers, Duchess of Richmond, with her late son Esme and her daughter Mary following the 2012 treatment

Examination of the painting before treatment at Tate in 2012 revealed that it had been selectively cleaned in the past;5 while there was one thick coat of varnish on the figures, there were three in the background. Examination of cross-sections through paint and varnish showed that the two extra layers of varnish in the background lay beneath the layer on the figures. There were extensive residues of a very early varnish lying deep in the brushwork on the figures, and strong light and high magnification revealed much old abrasion of the paint in the background, beneath the thick varnish. These varnishes were removed, but the residues of very old varnish from earlier attempts to remove varnishes remain trapped in the troughs of the brushwork. The old paste lining was removed manually, and a new lining treatment was carried out using woven polyester sailcloth and Beva-371, a synthetic resin. The stretcher is modern (fig.16). The painting was revarnished with MS2A, a polycyclohexanone resin, retouched with pigments bound in stable Paraloid B-72 acrylic resin, lightly varnished with Paraloid B-72, retouched further in MSA resin, and given a thin penultimate varnish with MS2A. These recent retouches appear very dark in the ultraviolet image (fig.14), in small areas across the surface and along the lower edge.

February 2022