Fig.1

British School, 16th century

Portrait of Sir Henry Unton 1586

Tate

T00402

Fig.2

X-radiograph of Portrait of Sir Henry Unton 1586

Fig.3

The back of the painting

The support is an oak panel composed of two vertical planks, butt joined with glue (fig.1). The left plank is 292 mm wide, the right 160 mm; the joint runs to proper left of the sitter’s face (fig.2). Dendrochronology revealed that the oak is of Polish/Baltic origin.1 The earliest extant heartwood ring dates from 1569. The wood varies from 8 to 10mm thick; toolmarking and a marked step at the joint on the back suggest this is the original thickness (fig.3).

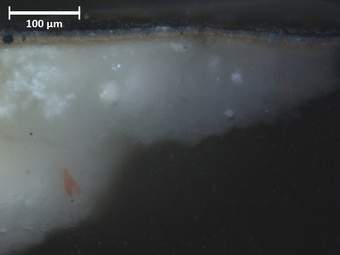

Fig.4

Cross-section through the grey background at the right, cut edge, 500 mm from the bottom edge, photographed at x200 magnification. From the bottom of the sample upwards, it shows: white chalk ground, average thickness 150 microns; thin, warm toned brown wash, 3 microns thick, containing white, black reddish earth colours and possibly red lead; grey paint of background mixed from white, black and fine orange particles in an opaque grey matrix; dark greyish brown paint of background; thick modern retouching

Fig.5

The same cross-section viewed in ultraviolet light, photographed at x200 magnification.

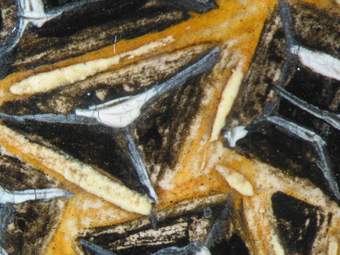

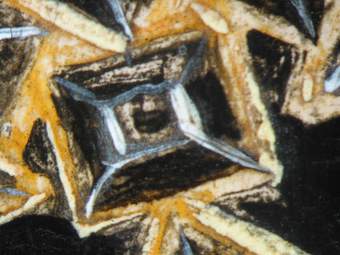

Fig.6

Cross-section through the grey background at the right, cut edge, 266 mm from the bottom edge, photographed at x225 magnification. From the bottom of the sample upwards: white chalk ground, 250 microns thick; pale orange coloured underpaint, up to 5 microns thick; grey paint of background, 7 to 10 microns thick; dark greyish brown paint of background; modern overpaint and varnish

The ground, whose thickness varies from 60 to 200 microns, is made of chalk and animal glue. It peters out within a few millimetres of the top, bottom and left edges of the panel but at the right it ends sharply at the edge, indicating that the wood has been trimmed slightly here. No priming is visible in the cross-sections (figs.4–6).

No underdrawing is evident with any method of examination. There appears to be thin but very dense white underpainting beneath the white satin doublet, perhaps to help create the effect of this shiny, opaque material. The background has a warm orangey brown underpaint, darker on the right than the left; it is more visible that it would have been originally due to the age of the paint. The shadowed half of the face seems to be underpainted in a similar tone. When underpainting the background, the artist left reserves for the figure and the hat.

The final shades of dark grey in the background were mixed from black, lead white, brown earths and fine red particles, and were applied mainly in one layer wet-in-wet except on the right where they were strengthened with a thin, greyish brown glaze. The final tones for the white doublet were mixed from lead white with fine black and opaque red pigment, and applied wet-in-wet to the underlying, dry white paint. Details such as lace and buttons were worked in with thick white paint. The face was done wet-in-wet on top of ground and underpainting. The flesh tones are composed of lead white, black and very finely ground opaque red. The lips were glazed slightly while wet. Highlights in the face were loaded with lead white.2

Fig.7

Detail of the face

Fig.8

Detail of the ruff and costume

Fig.9

Detail of the white costume

Fig.10

Detail of a button, worked wet-in-wet with a stiff brush

Fig.11

Detail of the sitter’s left eye

Fig.12

Detail of a pearl on the hat badge

Fig.13

Detail of central diamond in hat badge

Fig.14

Detail of impasto in shoulder cord and metal point

Fig.15

Additional detail of impasto in shoulder cord and metal point

Fig.16

Detail of red glazing over opaque red

Fig.17

Detail of gold braid

Elsewhere the painting was created wet-in-wet directly onto the ground, with each area clearly demarcated in advance. For the ruff the artist applied mixtures of white and black wet-in-wet. These white and grey mixtures were modified wet-in-wet with red and orange in the areas where the ruff appears to lie on top of the red and gold jacket. For the jacket, shades of red were mixed from red earth and red lead with lead white, black and glassy particles, and worked wet-in-wet on the panel. It is possible that these red tones were enriched finally with a reddish brown glaze, since largely lost through fading and abrasion. The yellow braid on the jacket was laid in first with opaque yellow composed of earth pigment with black, lead white, chalk and pipeclay. Detailing was applied wet-in-wet on top in lead-tin yellow, and glazed here and there with a red lake mixed with black in a brownish medium. All these features are illustrated in figs.7–17.

Most areas of the painting have become more transparent and darker with time, which has robbed the portrait of some of its solidity. The formation in many areas of lead soaps which have developed from the lead white pigment reacting chemically with the oil medium has contributed to the worn appearance.

Fig.18

X-radiograph of the top edge of the frame, showing nailed construction and metal curtain hooks

Fig.19

X-radiograph of the bottom edge of the frame, showing nailed construction

The painting was cleaned at Tate in 1962. The oak frame is contemporary with the painting and may be the original (figs.18–19).

March 2020