It might have taken until 1966 for Time magazine to call London 'The Swinging City', but pop culture had been making its mark in London (and everywhere else) for half a decade already. Time noted that the UK was exporting fashions, trends, music and language to the US – in a reversal of previous decades. The focus of consumer culture across the globe was shifting from the little woman in the home to the trendy young thing on the street.

Youth culture was driving the Swinging Sixties, from the blues and rock & roll-inspired sound of The Beatles, Mary Quant’s miniskirts or Haight Ashbury’s growing hippie community. By 1964, the idea of the youthful trendsetter was ingrained enough for The Beatles’ first film A Hard Day’s Night, to send it up.

Pop culture, everyday life, consumer items and advertising design all had their impact on the art world – most obviously in what came to be known as Pop Art. But it wasn’t a one-way street; the artistic avant-garde and the mass media crossed over, borrowed from and reflected each other in this period like no other before.

In New York in 1960, Claes Oldenburg displayed a found-object environment, The Street; at the Judson Theatre. With silhouette sculptures of figures alongside the detritus from the streets, it recalled the everyday, urban experience outside the gallery space.Oldenburg used the environment he’d created for The Street as the setting for his happening Snapshots from the City. In 1961 his interest in widely available commodities as subject matter was showcased in The Store, a shopfront which was both literally a store, where he made and sold plaster sculptures of food and consumer items as well as a space used as a setting for theatrical events. For his happenings at The Store: Store Days and Store Days II Oldenburg sewed huge, soft sculptures of some of these items: cakes; burgers and ice creams. The shop was a place where interactions took place, where cultures and purposes mingled, and Oldenburg’s chaotic Store jumbled making, display, selling and performance together.

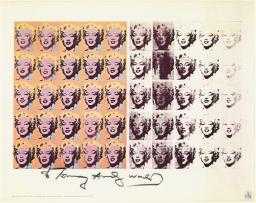

Andy Warhol

Marilyn Monroe

(1962)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

© 2024 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by DACS, London

The most famous of the Pop artists, Andy Warhol, began his working career as a successful commercial illustrator in the 1950s. In 1960, inspired by his admiration for artists like Robert Rauschenberg, Warhol resolved to focus on gaining recognition as painter, taking the commercial images all around him as his subject. His studio space in New York, known as The Factory, was (like Oldenburg’s Store) both the place he worked producing his sculptures, silk screens and films and the place he hung out and partied. It became a meeting place for artists, musicians, performers, filmmakers and other party people. By 1963, Warhol himself had become a celebrity, and had decided to concentrate on experimental filmmaking Sleep 1963 featured slowed down film of John Giorno sleeping, and lasted over five hours, while his eight-hour film of the Empire State Building was produced in 1964. His Screen Tests, where anyone he felt had ‘star quality’ was filmed for a moving portrait, illustrated his most famous quote, that ‘In the future everyone will be famous for fifteen minutes.’ Warhol also produced music, film and light spectacles, called The Exploding Plastic Inevitable with the Velvet Underground and Nico. The Velvets’ trademark dark glasses apparently date from this time , as the light show was often literally blinding.

Jonas Mekas

Diaries, Notes & Sketches a.k.a. Walden

(1964–9)

Tate

Warhol wasn’t the first to work in putting together film and light shows. A culture of fusing experimental filmmaking, light shows and music was taking off across the US and in Europe.

Film maker Jonas Mekas started Film Culture magazine in New York in 1954, which began by covering mainstream films but soon became the key publication on avant-garde film. In 1964 he founded the Film-Makers’ Cinematheque. Author John Brockman said that in 1965:

Mekas hired me to manage the Cinematheque. I was 24-years old at the time. One day he handed me a piece of paper with a list of about 50 artists, poets, dancers, film-makers, laid out his vision for a “new cinema” festival, wished me luck, and left the country, leaving me to produce “The Expanded Cinema Festival” which took place in November, 1965. The Festival included events/performances by Andy Warhol, Robert Rauschenberg, Claes Oldenburg, Nam June Paik, La Monte Young & Marian Zazeela, USCO, Carolee Schneemann, Kenneth Dewey & Terry Riley, and Jack Smith.

In 1957, in San Francisco, painter and filmmaker Jordan Belson and sound artist and composer Henry Jacobs put together the first Vortex Concert. Held in the 65-foot dome of the Planetarium at the California Academy of Science, Belson described it ‘as a series of electronic music concerts illuminated by various visual effects’. While avant-garde music was played, Belson used film projectors and the planetarium’s own lighting systems to create a spectacular light show, a huge modern magic lantern of abstract patterns and cosmic imagery. The sound design that Jacobs used in the performances was an early successful use of surround sound Disney’s Fantasia had a surround sound sequence in 1941, but the speaker system it required was too costly for wide installation in cinemas), and the first (what would now be called) immersive environment. San Francisco in the 1950s was the hangout of the ‘beatniks’, from writer Jack Kerouac to poet Allen Ginsberg, and continued as a scene for the anti-commercial, anti-militaristic counter culture. Though not explicitly linked, these colour, light and sound spectacles prefigured the Haight Ashbury psychedelic rock scene of the mid-sixties and the light shows of LSD-influenced hippie bands such as The Grateful Dead.

Also in the late Fifties, but back in New York, Stan VanDerBeek, who also had attended Black Mountain college and collaborated with Merce Cunningham and John Cage, began work on The Movie-Drome. It was to be a hemi-spherical dome-studio-laboratory-theatre in Stony Point, New York, which would combine a studio space with a setting for a ‘continuous magic theatre with performances’ where people would experience film projections all around them, not just in a single static rectangular screen. VanDerBeek was producing films intended for the Movie-Drome from 1957, which he began to build in 1963. VanDerBeek was excited by the moving image as an art form; as a ‘means of aesthetic expression’, but felt that categorising what he did as ‘experimental’ dismissed cinema as both a mass medium and an artistic one, like painting. His films such as 1959’s Science Friction used the cut outs from newspapers and magazines favoured by Pop artists, but animated them in absurd and satirical ways. Terry Gilliam took inspiration from VanDerBeek’s films when he went on to create some of the animated sequences in Monty Python’s Flying Circus.

Alongside filming some of the many happenings going on in New York at the time, VanDerBeek also worked with engineers at Bell Telephone Labs and MIT to produce early computer generated images and films, and conceived of a ‘Culture Intercom’ that would use a ‘non-verbal international picture-language’ to be transmitted by telephone and television across the world, ‘An image library, a culture de-compression chamber, a culture inter-com.’ Though he probably didn’t imagine in 1966 that the universal language would be videos of cats doing tricks, the growth of online video does seem to capture some of the spirit of the Culture Intercom. However, TV was the true mass medium throughout the twentieth century, and the programme varied much more widely than we imagine today. Television documentaries did meet artists at the cutting edge and screen interviews and documentation, bringing the avant-garde to a wider, though still limited, audience.

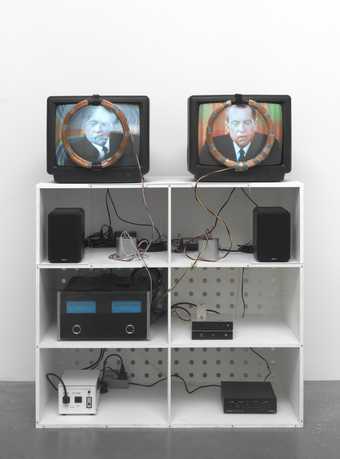

Nam June Paik

Nixon

(1965–2002)

Tate

Korean artist Nam June Paik, now considered to be the first video artist, was also the first artist to use the TV set as his medium. He began working in music and performance while a student in Germany, where he met John Cage in 1958, and the founder of the Fluxus group, George Maciunas, in 1961. Fluxus artists made often playful interventions in gallery spaces and in the world, and Paik helped to organise Fluxus ‘actions’ in Europe (as well as performing in many of them) in the early 1960s. Dick Higgins said, ‘Fluxus is not a moment in history, or an art movement. Fluxus is a way of doing things, a tradition, and a way of life and death’, while Fluxus group member Ken Friedman put it this way:

As I see it, Fluxus was a laboratory. The research program of the Fluxus laboratory is characterized by twelve ideas: globalism, the unity of art and life, intermedia, experimentalism, chance, playfulness, simplicity, implicativeness, exemplativism, specificity, presence in time, and musicality.

In 1963, Paik’s first solo exhibition Exposition of Music – Electronic Television ran throughout the architect Rolf Jährling’s gallery and house as a ‘total event’. The show was open for two hours a day for ten days, and included his first television works, where Paik modified and distorted the signal coming through a series of modified TV sets.

I did not consider myself a visual artist. But I knew there was something to be done in television and nobody else was doing it, so I said “Why not make it my job?”.

Distinctions between artist and agent provocateur, pop star and post-modern muse, were becoming blurred: pop culture influenced the art world, while the art world influenced pop culture. The first time John Lennon met the (now most famous) Fluxus artist Yoko Ono at the private view of her solo (Fluxus) show at London’s Indica Gallery in 1966.

As Lennon recalled:

Then I went up to this thing that said, ‘Hammer a nail in.’ I said, ‘Can I hammer a nail in?’ and she said no, because the gallery was actually opening the next day. …So there was this little conference and she finally said, ‘OK, you can hammer a nail in for five shillings.’ So smart-ass here says, ‘Well, I’ll give you an imaginary five shillings and hammer an imaginary nail in.’ And that’s when we really met. That’s when we locked eyes and she got it and I got it and that was it.

This meeting, and the creatively significant relationship that emerged from it, is telling. It can be seen as indicative of the ways in which the specific cultural conditions of the mid-20th century afforded novel and productive collaborations between artword figures and those from popular culture. And under the banner of Fluxus, we are able to trace how the reciprocal interactions between art and pop, an emerging mass media, and a backdrop of radical social change, fostered the emergence of new modes of cultural production.