With A World in Common: Contemporary African Photography now open at Tate Modern, let’s look at some of the extraordinary images giving us a vivid glimpse into Africa’s past, present and future.

Get to know 8 photographers who explore Africa’s diverse cultures and histories

Discover powerful African stories told through photography

Ruth Ginika Ossai: Empowering Identity

Ruth Ossai, Student nurses Alfrah, Adabesi, Odah, Uzoma, Abor and Aniagolum. Onitsha, Anambra State, Nigeria, 2018 Photograph © Ruth Ginika Ossai

Ruth Ginika Ossai is interested in how photos can transport memories across time and place. Based in Nsukka, Nigeria and the UK, she started taking photos of her life in Nigeria and making photo albums to share with family in Yorkshire. Working closely with her local Nigerian community, Ossai creates empowering portraits where her models have ‘total control over how they portray themselves through choices in backdrops, poses, or their own personal style.’

Ossai also uses striking floormats and vibrant backdrops bursting with colour, inspired by special effects in Igbo gospel music videos and popular Nollywood films. ‘I wish my images to fill my subjects with power and agency… to allow their true selves to shine through,’ she says.

Sabelo Mlangeni: Intimate Portraits of Gay Life

Miss Gay Ten Years of Democracy, Bheki Mndebele at Wesselton community hall 2003

Purchased with funds provided by Mercedes Vilardell, Harry and Lana David, Emile Stipp, Peter Warwick, and Diane Frankel 2023

Taken over six years in small towns in the Mpumalanga province, Sabelo Mlangeni's Country Girls is an intimate portrait of gay life in the South African countryside. With glamour and grittiness, the powerful series celebrates queer people and their everyday lives. The photographs are dedicated to the heart of the community: local drag queens, hairstylists and beauty pageant contestants, all dressed in tenderly handmade clothes and hand-me-downs.

Mlangeni vividly captures groups coming together for parties, birthdays and funerals full of love and friendship. Outside South Africa, homosexuality is illegal and condemned as un-African or un-Christian. Despite the threat of violence and discrimination, Mlangeni’s vibrant portraits highlight the resilience of queer people who have carved out spaces to work, love, and find community.

Kiripi Katembo: A Doorway into a Dream

Kiripi Katembo Avancer, Un regard series 2008-2013 © Kiripi Katembo, Courtesy Kiripi Katembo Siku Foundation & MAGNIN-A Gallery, Paris

Kiripi Katembo’s Un Regard is a series of photographs of the city of Kinshasa, the capital of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Katembo took his camera to the streets to capture reflections of the city and its people in pools of water. Katembo presents the images upside down, magically transforming Kinshasa into a dream-like world of moody shadows and mysterious objects – a far cry from its usual chaotic hustle and bustle.

‘Even though the picture looks surreal, I wanted it to reflect the reality of life in Kinshasa – these big contrasts of colour, bright oranges and yellows, the taxis and the billboards,’ he says. ‘For me, these reflections are like windows into another, more beautiful reality... a doorway into a dream.’

Khadija Saye: Spirituality and Ritual

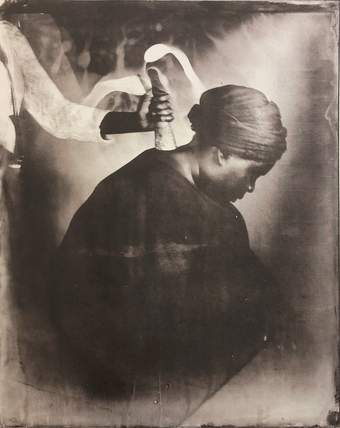

Nak Bejjen, 2017 Khadija Saye From the series: Dwelling: in this space we breathe Wet plate collodion tintype on metal 250 x 200 mm

Image courtesy of the Estate of Khadija Saye Copyright © 2017 Estate of Khadija Saye. All Rights Reserved. In memory: Khadija Saye Arts at IntoUniversity

These striking self-portraits by Khadija Saye explore traditional Gambian spiritual practices as a way of connecting to ancestral homelands. In the photos, Saye performs a series of rituals using sacred objects. Saye’s head bows in prayer in Nak Bejjen, Wolof for cow horn, while a figure holds a horn-like object to the back of her neck, suggesting a technique used by Gambian healers to draw out impurities.

Saye created the image using a time-consuming 'wet collodion' technique – a process the artist cannot fully control. ‘Within this process, you surrender yourself to the unknown, similar to what is required by all spiritual higher powers: surrendering and sacrifice,’ Saye explained.

Zina Saro-Wiwa: The Power of Masquerade

Zina Saro-Wiwa From The Invisible Man series 2015 Courtesy of the artist and Tiwani Contemporary © Zina Saro-Wiwa

In her series of masked self-portraits, Nigerian-born artist Zina Saro-Wiwa explores masquerade hoping it will help her heal. The title, The Invisible Man, refers to the men who have disappeared from Saro-Wiwa's life after she lost several male members of her family. Masks are typically only worn by men. But after Saro-Wiwa went back to her ancestral homeland in 2013, she started to explore the practice and challenged tradition by commissioning her own mask.

‘Women are culturally required to carry huge burdens, physically and emotionally and are therefore more than capable of wearing the mask and representing their own culture,’ she explains.

Kiluanji Kia Henda: Empty Buildings, Empty Homes

Kiluanji Kia Henda

Rusty Mirage (The City Skyline)

(2013)

Tate

Rusty Mirage depicts an imaginary city in the Al-Araz desert, Jordan. Kiluanji Kia Henda used a traditional Angolan visual storytelling technique inspired by geometric sand (‘sona’) drawings to create the buildings' outlines. During a construction boom in Luanda (Angola) Henda recreated abandoned areas of cities around the world to highlight the link between failed building projects, poverty and homelessness.

‘People looked at these impressive new buildings appearing in the city as a symbol of development, but the vast majority would never have the opportunity to enter such spaces,’ Henda explains.

George Osodi: Visions of Royalty

George Osodi

HRM Agbogidi Obi James Ikechukwu Anyasi ll, Obi of Idumuje Unor (in Palace), 2012

Digital C-print on paper

George Osodi

George Osodi’s Nigerian Monarchs is a series of richly colourful portraits of Nigerian kings and queens who ruled many different regions and ethnic groups. During the late 19th century British forces merged hundreds of kingdoms to form the artificial boundaries of modern-day Nigeria. The monarchs slowly had their constitutional powers taken away, however they still play an important role as guardians of cultural heritage and community today.

‘Nigeria is not only rich in natural resources but also in its religious and cultural diversity,’ Osodi explains. ‘I believe this should be a source of strength and unity among the country’s various ethnic groups, rather than something that creates division and instability.’

Sammy Baloji: A Land Forgotten

Sammy Baloji

Untitled 17

(2006, printed 2020)

Tate

© Sammy Baloji; courtesy of the artist and Galerie Imane Farès

Sammy Baloji was born in Lubumbashi in the Democratic Republic of Congo’s Haut-Katanga province, a place rich in minerals like copper, cobalt and uranium. His work powerfully explores the region’s complicated history of exploitation by Belgian colonial powers and authoritarian governments and companies.

In his series Memoire, Baloji superimposes colonial-era images onto contemporary photographs of ruined mining structures. He joins two views of the same landscape together to symbolise the spaces and people scarred by colonialism and globalisation. ‘I think reality has a kind of complex relationship with past, present, now, yesterday or today,’ Baloji says.

A World in Common: Contemporary African Photography is on at Tate Modern until 14 January 2024