Photo: Michael Holtz/Photo12

Who is he?

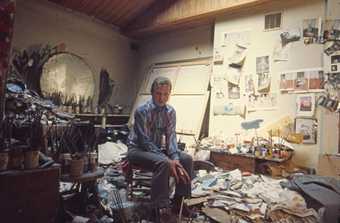

Francis Bacon (1909–92) was a maverick who rejected the preferred artistic style of abstraction of the era, in favour of a distinctive and disturbing realism. Growing up, Bacon had a difficult and ambivalent relationship with his parents – especially his father, who struggled with his son’s emerging homosexuality.

This contributed to a troubled childhood; he ran away from school, and subsequently drifted through the late 1920s and early 30s in London, Berlin and Paris, living off his allowance and occasional jobs, and dodging the rent. When in London, he lived in the epicentre of the bohemian scene; a regular in Soho, he led a hedonistic life.

From the mid-1940s his work met with critical success, establishing his reputation. Today, he is recognised as one of the most important painters of the twentieth century.

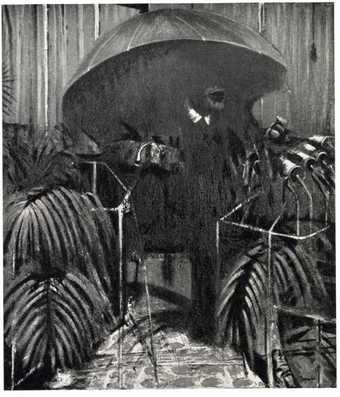

Francis Bacon Painting 1978

Oil on canvas

1980 x 1475 mm each

© The Estate of Francis Bacon/DACS 2008

Private Collection, London Prudence Cuming Associates Limited

How did Bacon come to be an artist?

Bacon did not become an artist through any traditional route: he didn’t attend art school, for example, or serve a conventional apprenticeship. In early professional life, he worked in interior design, but decided to abandon this and take up painting after seeing an exhibition of Picasso’s at Paul Rosenberg’s Paris gallery in the late 20s. Picasso’s representations of the body as bone-like, biomorphic structures revealed to Bacon the ‘possibilities of painting’. He later acknowledged Picasso as a key influence and reference point.

I’ve had a desire to do forms, as when I originally did three forms at the base of the crucifixion. They were influenced by the Picasso things which were done at the end of the ‘twenties. And I think there’s a whole area there suggested by Picasso, which in a way has been unexplored, of organic form that relates to the human image but is a complete distortion of it.

What are his key works?

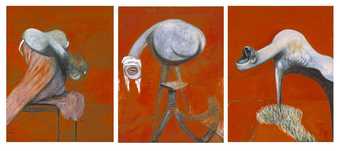

Francis Bacon

Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion c.1944

© Tate

When the triptych, Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion 1944, was first exhibited at the end of the war in 1945, it secured Bacon’s reputation. Chris Stephens, Head of Displays and Lead Curator, Modern British Art at Tate Britain called the work ‘a turning point in the history of British art. It’s one of the masterpieces in the Tate’s collection… It’s a work that was seen immediately as a brutally frank and horrifically pessimistic response to the Second World War. It was first exhibited in April 1945, and though the two were not directly related, the fact that this painting was unveiled the month that the concentration camps were revealed to the world, inevitably led to the way it has been understood as a statement of human brutality and suffering.’

Bacon suggested he had intended to paint a larger crucifixion beneath which these would appear. Speaking about this work in an interview in 1955, the artist said: ‘I have no religious feelings but at the same time I was [going to] do a crucifixion and put these figures around the base of it. And the only reason I ever used the crucifixion [was] because it was an armature on which I could hang certain sensations.’

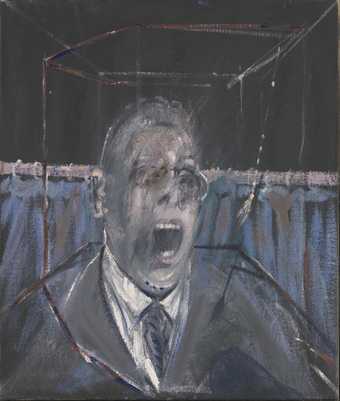

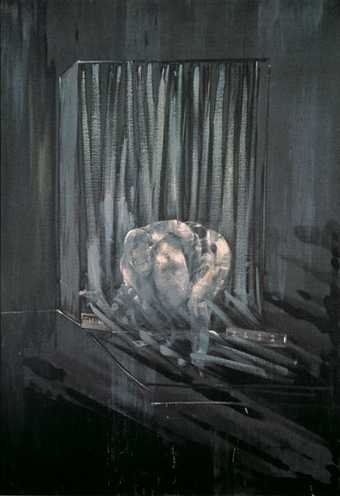

Francis Bacon, Study for a Portrait 1952, oil and sand on canvas, 66.1 x 56.1 cm

© Estate of Francis Bacon, all rights reserved, DACS 2016

Study for a Portrait 1952 dates from a crucial point in Bacon’s engagement with portraiture; Bacon painted his first head in isolation in 1948, and his contemporary Lucian Freud, a close friend, sat for Bacon’s first identifiable portrait of an individual in 1951. As is the case with other examples of the artist’s work in which he has employed a cubic, architectural framing device, or space-frame, implicit in this painting is a sense that the central figure has been trapped by the transparent cage that surrounds him. Asked by the critic and curator David Sylvester about the persistence of this technique, Bacon explained that the device was used simply to ‘concentrate the image down’.

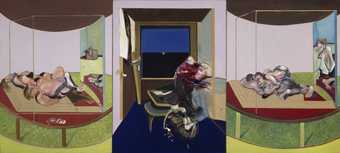

Francis Bacon, 1909-1992

Triptych 1967

© The Estate of Francis Bacon. All Rights Reserved. DACS 2016. Gift of the Joseph H. Hirshhorn Foundation, 1972. Courtesy of Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. Photo: Lee Stalsworth

For Bacon, the format of Triptych 1967 was a tactic, in some ways akin to the cubic cages, to isolate images from each other in order to ‘avoid story-telling’. References to poetry and drama became a central element in Bacon’s work in this period. Formerly titled Triptych Inspired by TS Eliot’s ‘Sweeney Agonistes’, rather than illustrating the verse drama (first published in 1926), this work can be understood as evoking the experience of reading the themes of violence and life’s futility in Eliot’s poetry.

Francis Bacon Triptych – In Memory of George Dyer 1971

Oil on canvas

1980 x 1475 mm each

© The Estate of Francis Bacon/DACS 2008 Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel

What the critics say…

[Bacon is] quite simply the most extraordinary, powerful and compelling of painters … His images short-circuit our appreciative processes. They arrive straight through the nervous system and hijack the soul.

Rachel Campbell-Johnston, Art Critic

I think Bacon is on his own, really. I mean, he had a very, very dark view of the world… And that’s probably why I love Bacon paintings, because when I first saw them, they reminded me of sort of spaces I’d imagined in nightmares, which is why he’s great.

Damien Hirst, Artist

His life was kind of pretty chaotic and he just did whatever he wanted to do, drank whatever he wanted to drink, slept with whoever he wanted to sleep with; he was a maverick within society… Francis Bacon’s paintings aren’t static, they’ve got total movement…

Tracey Emin, Artist

Nobody has found more wicked energy in contemplating the cage than Francis Bacon… Cages provide areas for Bacon to stage his ferocious meditations on human anguish and savagery, but they also assume more distorted forms, shifting like the spaces within a bad dream.

Charlie Fox, Writer

Francis Bacon, Study for Nude 1951

Oil on canvas

1980 x 1370 mm

© The Estate of Francis Bacon/DACS 2008

Collection of Samuel and Ronnie Heyman

Bacon in quotes…

You know in my case all painting – and the older I get, the more it becomes so – is accident. So I foresee it in my mind, I foresee it, and yet I hardly ever carry it out as I foresee it. It transforms itself by the actual paint. I use very large brushes, and in the way I work I don’t in fact know very often what the paint will do, and it does many things which are very much better than I could make it do. Is that an accident? Perhaps one could say it’s not an accident, because it becomes a selective process which part of this accident one chooses to preserve. One is attempting, of course, to keep the vitality of the accident and yet preserve a continuity.

I use the frame to see the image – for no other reason. I know it’s been interpreted as being many other things… I cut down the scale of the canvas by drawing in these rectangles which concentrate the image down. Just to see it better.

I think that the very great artists were not trying to express themselves. They were trying to trap the fact, because after all, artists are obsessed by life and by certain things that obsess them that they want to record. And they’ve tried to find systems and construct the cages in which these things can be caught.