David Aukin: The word charisma is overused but when he entered a room he had such energy and exuberance.

Because it was the first artist studio that I had ever been into, surrounded by his paintings and easels and drawings and everything and a couch where he slept.

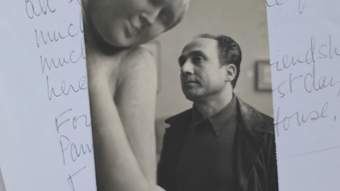

My name is David Aukin and I'm the son of Charles and Regi Aukin, and they were close friends of Jankel Adler.

Glenn Sujo: I'm interested in Adler's world but I'm also interested in the fact that in Adler we have a figure who is both part of the Jewish world - he grew up in a traditional Yiddish speaking, Orthodox observant family - and his other journey is this journey into assimilation and modernism.

Aukin: I would say even more so Jankel's life was one long journey from Łódź where he was born through to Germany. When Hitler came to power he obviously had to leave Germany and he moved around again and ended up in Paris, had a studio I think next door to Paul Klee and they were very good friends.

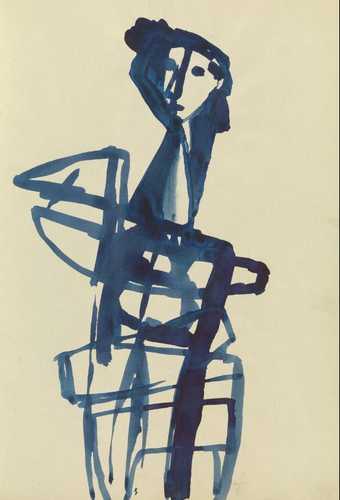

He obviously was a compulsive drawer. He just, he had to have a pencil in his hand and he had to have a sketchbook and he would just work away.

Sujo: What we're looking at is a life across, what, 1927 through 1949 in these schedules. So these sketchbooks actually materialise this man's thought process his thinking life and his movements. So when I look at this, I can see Adler getting on those boats at Dunkirk for the evacuation out of France to British shores. He's carrying this under his arm.

He was brought to Glasgow, he was in an internment camp for a while. He brought with him the whole continental attitude towards painting which was largely unknown and it was very invigorating and exciting from Scottish artistry which in Glasgow even during the war was apparently very strong and ongoing.

What we have here is perhaps the first of the Glasgow sketchbooks and we sense that Adler is trying to lay down some roots in Glasgow. And as we turn the pages indeed he steps in to the congregation.

What we see is that the onion dome, the ritual dome head covering that the Hassan is wearing becomes this setting sun shape. And below that the congregation dissolve into this shimmering mass.

It is a very poignant moment and one senses that there is a crisis in the Jewish world.

Aukin: When Jankel Adler died my father became the executor of the will.

So the first thing he had to do was to preserve everything that was in the studio, among those were the sketchbooks which he put into a large portfolio and I don't think people really looked at them for many years.

Sujo: This is a glorious sketchbook and then this amazing page, Adler reclining here at the base along the bottom edge.

There's a second curious figure here, a kind of echo, also a reclining figure appears to be a system of bunk beds and then clothes thrown onto a line, pyjama tops and bottoms.

And I wanted then to move on to what seems to me to be a very final statement and one that probably reflects Adler's state of mind.

The painting he titles Treblinka, Polish for the extermination camp.

And I sense that there is a strong connection here with a process of reflection at the close of his life.

Aukin: When I was sort of 13, 14 years old we had to catalogue all the drawings and all the sketches and all the artworks.

And each one had to come out and had to be numbered.

And we would spend the weekend or the afternoons working on this which is the last thing I wanted to do as a teenager, I can assure you.

But Adler just became part of my vocabulary, my visual vocabulary.

So it's very difficult for me to be at all objective about them.

I look at them and they're part of my life.