This exhibition brings together the best of Lowry’s industrial scenes and landscapes to encourage us to think more deeply and widely about Lowry’s work but also to argue for his status as Britain’s preeminent painter of the industrial city.

This room looks particularly at street life and how Lowry was able to engage with some of the poorest areas in Manchester and Salford. He worked, of course, as a rent collector for most of his life which gives him a very unique access and intimacy with the inhabitants of some of these poor slums. This is Street Hawker from 1929. It’s a wonderful picture, I say wonderful but it’s a picture of doom and gloom actually. What we see in the foreground here is a hawker’s cart where people could buy and sell and it all looks very innocent but of course when we realised that a hawker sold on tick, which means that they sold on credit and often charged high interest, we kind of understand that a lot of the people buying here were probably in quite a lot of debt which helps to explain a particular drama which is happening here and when we scan over the buildings we notice that people have started to come from their windows to have a look at the dramatic scenes that are unfolding on the street.

I think it’s a comforting fiction that Lowry’s work belongs to a particular moment in British history. His works aren’t simply just about memory, and I think the paintings on view in this room could equally be other cities industrialising around the world today. We’ve brought together some deeply melancholic, deeply toxic looking landscapes and urban scenes and as a landscape painter, Lowry really wanted to show us what industrialisation had done to the world.

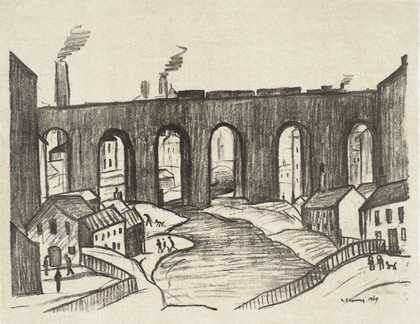

This is a very important picture, Industrial Landscape, Wigan from 1925. It’s a very early attempt at the industrial scene, but I do think it’s a particularly powerful picture, very, very expressive handling of paint. Lowry is really trying to show us the effects of the dark, satanic mills which he’s obviously become very obsessed by because you can see them, you know, these belching chimneys receding into the distance and in a lot of these paintings Lowry paints rivers as contaminated pools of water that sort of seep and express all of this dirt and gloom.

I think visitors to this room are going to see something very unexpected, for the very first time all seven of Lowry’s late industrial panoramas. And what’s so special about this room is that the scale and the mood suddenly become much more expansive. The picture at the very end is one of my personal favourites, it’s Industrial Landscape from 1955 from the Tate collection. It’s a painting where Lowry has really let himself go. The sky is a real tour de force of painting, these sort of belching chimneys and these wonderful, muted colours lend the work a really dream-like quality.

One of the ambitions of the show is to reveal Lowry’s connections to French modern life painting and really what he takes from Pizarro, from Seurat, from Van Gogh, is this wonderful sense of atmosphere.

It’s a fiction as well that Lowry painted street scenes from life. These are very much composite images built up over thirty years of his very close observations of industrial life. And in a letter to the Tate gallery, Lowry wrote about how he hadn’t got a clue about how to start and how this canvas was going to turn out but by adding little elements like the Stockport Viaduct or a church or a chimney here, the image would suddenly come to him to form one magnificent work.