The prohibition that Psyche breaks, when she lights a lamp and looks on the sleeping form of her lover beside her, could only belong in a poetic order of reality. Could it ever be so pitch dark, even in the depths of the night, that she couldn’t tell a cannibal beast of hideous aspect from the delightful youth, all golden and curly, who appears in the glow of her forbidden lamp? Even discounting her other senses, she would have glimpsed something of her mysterious husband. The darkness must rather be hers: the innermost recesses of her fantasy, which has been filled with shadows by her sisters’ malicious talk about the nature of her bridegroom. Psyche is in the dark about her own story, and her worst fears about her fate have been murkily stirred.

When she illuminates the scene, at that moment when the drop of oil falls from the lamp onto Cupid’s shoulder and he wakes, everything around her vanishes – the gorgeous castle, her fairy attendants and magical banquets and apparel and diversions and visual enchantments. Her previous blindness to her beloved’s identity had opened another eye, the interior eye of fantasy, and, in every respect of her existence with Cupid, she was living in a dream world.

The story of Cupid and Psyche appears within the frame of Apuleius’s initiatory romance, Metamorphosis or The Golden Ass, and Charlotte Brontë read it in translation in the pages of Blackwood’s Magazine, to which her father subscribed. The story suffuses later fairy tales – Beauty and the Beast above all – and their multiple affinities to Jane Eyre have often been noted, for Charlotte Brontë frequently invokes the canon of classical and nursery romances (Bluebeard perhaps more even than Cinderella). Even the blindness of Mr. Rochester at the conclusion of the novel casts him, it has been proposed, as the blind god of love. But these narrative links of motifs and plot elements do not close quite so tightly with the true sympathy between Jane Eyre and fairytales that Brontë kindles at the core of her book; this sympathy leaps out of the persistent liveliness of interior mindscapes, in contrast to the dark, dreary, crushing realities around her heroine. Just as Psyche’s existence is brilliantly illuminated when she’s living in the dark of her own dream world, before she comes down to earth (literally) after lighting the lamp, so Jane Eyre is taken out of herself into a more vivid, meaningful life by her interior life of thoughts, reading, the stories she remembers Bessie Lee telling her, the paintings she makes herself, and her various stratagems of retreat from her circumstances. Jane Eyre is possibly the earliest novel written in the first person of a child: Jane is ten years old when the book opens. But it is also a novel that, written in confessional narrative manner, tells what occurs outside through the emotional and fantastic voyaging of its heroine’s imagination.

Again and again Jane is confined, sometimes against her will, sometimes of her own accord: in an early piece of scene-setting, she is locked in the dark chamber where John Reed died and is so terrified by the dead man’s presence that she has a fit. This is only the first of a sequence of experiences when, for better or worse, imagination takes over Jane’s being.

Such an emphasis on the fire in the mind and the dark outside might perhaps reveal, without saying much more, how Paula Rego of all artists would respond to Jane Eyre. Paula Rego has been making images out of stories since she was a child, and if anything can be said to offer a consistent thread through her fertile and multi-faceted production it is this: she has been a narrative artist all along, and one whose stories are not reproduced from life as observed or remembered, but from goings-on in the camera lucida of the mind’s eye. Rego hasn’t lost in adulthood the energy of the child’s make-believe world: ‘It all comes out of my head,’ she says. ‘All little girls improvise, and it’s not just illustration: I make it my own.’

The spinal cord that runs through Rego’s oeuvre paradoxically joins intense looking out with even more intense looking in. In the last decade, often working from life models, she has developed a concentrated realist technique in draughtsmanship and paint: to render the texture and play of folds of dress and fabric, the gnarled feet, wrung hands, lined even seamed countenances of her characters, the dynamics of their conversation, interlacings, blows, and exchanges. But all this absorption in what goes on in the world of three dimensions and real people serves extreme acts of visual imagination, sometimes impossible to enact in any other dimension: the extraordinary image Loving Bewick, for example, when Jane kisses the pelican’s beak with an expression of eucharistic rapture. The composition recalls the picture of ‘Baa baa black sheep’ from Nursery Rhymes, in which a giant ram embraces a little girl, and it also harks back to a Renaissance Leda. Paula Rego says that she became interested, when reading the novel, in the paintings that Jane herself looks at, and Loving Bewick interprets the passage, at the start of the book, when Jane describes how she loses herself in Bewick’s History of British Birds, and travels through its pages to the ‘solitary rocks and promontories’, the ‘forlorn regions of dreary space’, and ‘death-white realms’ haunted by the book’s subjects:

Each picture told a story; mysterious often to my undeveloped understanding and imperfect feelings, yet ever profoundly interesting: as interesting as the tales Bessie sometimes narrated on winter evenings. and when, having brought her ironing-table to the nursery hearth, she allowed us to sit about it, and. fed our eager attention with passages of love and adventure taken from old fairy tales and other ballads.

‘With Bewick on my knee, I was then happy.’ In the print of Jane billing the pelican’s beak, Rego introduces a note of true sustenance: it is through the mind-food of books and pictures that Jane survives.

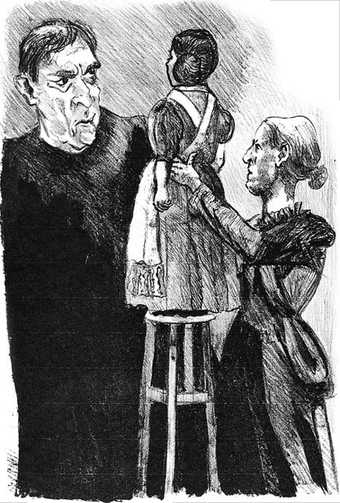

Brontë and Paula Rego share an imaginative ardour that abolishes the veil between what takes place in fact and in fantasy. As storytellers, they really are kith and kin: Rego reproduces the psychological drama in the book through distortions of scale, cruel expressiveness of gesture, and disturbingly stark contrasts of light and welling shadows. The long, lugubrious, moralising face of Mr. Brocklehurst in The Inspection looms as large as the little girl’s whole upper body and twice its bulk: Jane standing on the stool, held by Bessie, becomes a tiny, breakable poppet.

In Paula Rego’s work, in her ‘artist’s dreamland’, the peculiar and the elfish twist and turn with a similar rebellious vitality. And they do so for reasons that Jane Eyre’s did, mirroring Charlotte Brontë’s, over a hundred and fifty years ago. Rego has explored, in a myriad different sequences of pictures, the conditions of her own upbringing in Portugal, her formation as a girl and a woman, and the oscillation between stifling social expectations and liberating female stratagems.

At one point Jane Eyre protests,

Women are supposed to be very calm generally: but women feel just as men feel; they need exercise for their faculties, and a field for their own efforts, as much as their brothers do; they suffer from too rigid a restraint, too absolute a stagnation, precisely as men would suffer; and it is narrow-minded in their more privileged fellowcreatures to say that they ought to confine themselves to making puddings and knitting stockings, to playing on the piano and embroidering bags.

This segues without any obvious link to a paragraph which begins: ‘When thus alone, I not infrequently heard Grace Poole’s laugh.’ The disturbing sound of the woman confined and invisible (the madwoman in the attic), introduced in counterpoint to Jane’s thoughts about the constrictions on a woman’s life, suggests that her predecessor, Bertha Mason, the crazy Creole wife Mr. Rochester keeps upstairs, offers a horrible example of what can happen within a marriage. Bertha is Jane’s potential shadow double, the embodiment of a possible fate, and figures in the story like the ghoulish cautionary tale Mr. Brocklehurst thrusts at Jane: ‘…especially that part containing “An account of the awfully sudden death of Martha G-, a naughty child addicted to falsehood and deceit”,’ Brontë shows little compassion for Bertha Mason, but rather communicates the profound horror of her degradation, just as in Villette she also recoils without pity from the ‘cretin’ who terrifies Lucy Snowe. But unconsciously, Brontë strikes the reader as taking such matters personally, repudiating what she most fears will be the outcome of a narrow, suffocating, oppressive, loveless and directionless life.

Paula Rego’s portrayals of Jane do not prettify her as most of the jacket illustrations have done over the years, but remain faithful to the novel’s insistence on her plainness of feature, that makes her ‘such a little toad’ in the eyes of the bitter lady’s maid, Abbott; in so doing, in depicting Jane as neither slender nor graceful nor even jolie laide, Rego closes the distance between Jane Eyre and Bertha Mason, and illuminates the fate they could share, if Jane did not use her strength and originality of character to withstand society’s sentence on genteel women.

Girlhood and its appetites have inspired Paula Rego’s picture-making for over 30 years, and her works in this vein include the brilliantly fluent and mischievous sequence of paintings The Vivian Girls, inspired by Henry Darger’s extraordinary, epic scroll novel, populated by heroines, part Enid Blyton schoolgirls, part Surrealist femmes-enfants. Furiously intent young women, capricious, cruel, wilful in their confined domesticity, attend to one another or to animals or to daily, banal tasks; the scenes Paula Rego summons up dramatise the limits on female expectation imposed on Rego in her youth. For although she comes from a liberal family, she was steeped in the culture of Salazar’s dictatorship, founded on the Catholic church, the army, and the idealisation of Woman as wife and mother. The perverted uses of female power, when squeezed behind the scenes, or into the sewing room and the kitchen, erupt in Rego’s imagery with seemingly irrepressible force; she brims over with the same keen, impassioned sense of its malignity as Charlotte Brontë does in her creation of Bertha Mason.

To communicate dream worlds on the one hand, and to interfuse them with social critique on the other, Paula Rego has found the print medium supremely apt, in its spontaneity of execution and its long relation to storytelling. She has long defied prejudice against narrative painting, and has reclaimed illustrated tales for grown-up readers. She has absorbed the dramatic expressiveness of European commercial illustrators such as Max Klinger, Gustave Doré and Steinlem, who were working for the new picture press in the late-19th century. These have shaped her book illustration far more than the ornamental fairytale specialists, Arthur Rackham and Edmond Dulac. The graphic arts of fashion, advertising, of the boulevard, and the reportage of fait divers in 19th-century modernity fuse across the years with the perceptive, instant seizing of a moment, of an encounter, as in a Guercino drawing or an Orazio Gentileschi painting (both skilled at narrative gesture, and artists she loves).

When I was first reading the heady fictions of Conan Doyle and Rider Haggard, they came with illustrations, in the copies of the Strand Magazine my father had, and in the editions of She or King Solomon’s Mines issued for both children and adults in the Fifties. The pictures made a point: singling out a moment, they pierced through the veil of words and materialised a kind of essence of story. I shall never forget the thrill of an image under which was written: ‘It was the footsteps of a gigantic hound’ (although now, I feel, Conan Doyle can’t have written footsteps, but something like mark or track, surely.) Flicking through volumes that I still have from those years, I see that the artists used acute angles, raked perspectives, plunging viewpoints to accentuate the drama, which the captions intensified even more: ‘Another Secret Passage’, ‘A Queer Discovery’.

Picture books for children today don’t serve to heighten or punctuate the text: image and word combine and flow, like voices in a duet. Rego’s responses to a classic tale of mythical aura, like Jane Eyre, translate the novel’s character into another medium, reproducing its mood and its texture in kinetic line and moulding shadows. The benightedness of Jane’s state finds its correlative in the inkiness from which she materialises before our eyes; the dynamic nature of her resistance to her fate leaps in the vitality of her contours, and so forth: the visual technique matches narrative wordplay in reciprocal counterpoint. In a recent study of mental picturing, Dreaming by the Book, the American critic Elaine Scarry offers some highly original insights into the relationship between daydreaming, reading, and visualising, which throw light on the work of an artist like Paula Rego. She draws attention to the intrinsically dreamy properties of some phenomena, such as gauze or clouds or rain, which align them with objects of reverie which cannot be summoned up in their solid substance by the mind’s eye. ‘We might say’, she writes, ‘that in fog the physical universe approaches the condition of the imagination.’ Later, she adds, ‘It is not hard to imagine a ghost successfully. What is hard is successfully to imagine an object, any object, that does not look like a ghost.’

It is this weakness of imaginative projection, for most of us, that lends such power to technical media that simulate the stuff that dreams are made on: daguerreotypes, phantasmagoria, lantern slides, and film replicate the thinness, spectrality, and fugitive aspects of conscious, mental acts of visualisation. These comments on cognitive capacity offer a context for thinking about Rego and about the distinctive principles of book illustration, for what she achieves is precisely that solidity, that density of presence, that stable durability that usually elude the mind’s eye of the reader. But – and this but is a most important modifier – her images do not realise Jane Eyre or other figures as in the literal enactments of contemporary full-colour cinema: they retain dreamlike qualities. In the typical realist television adaptation, there are so many historic locations and vehicles, props and costumes, such heaps of furniture and whole archives of ornaments, but drawing out of the mind straight on to the plate or the stone doesn’t need the half of all that paraphernalia: in its grasp of mood and atmosphere, of the dream feeling, just a minimum of external detail is necessary.

Paula Rego is able to record that coming-into-being of her dream world and, as she sees with Jane’s ‘spiritual eye’, through Charlotte Brontë’s dramatic storytelling, through its heroine’s trials and survival back to her personal experiences of benightedness; her work helps release her viewers from that state through a different way of seeing, as when Psyche struggles through one kind of darkness into another.