Introduction: What are materials?

Anya Gallaccio

preserve ‘beauty’

(1991–2003)

Tate

© Anya Gallaccio. Courtesy the artist and Thomas Dane Gallery.

Materials are what things are made from. Materials have different qualities: they can be smooth or rough; hard or soft; heavy or light; fragile or indestructible. Artists choose materials because of their particular qualites. The same material can be used in very different ways to achieve very different results. The twentieth century saw artists experimenting with unexpected materials. Everyday objects, textiles, industrial substances, natural phenomena and even things we can’t touch or see (such as sound) found their way into art.

Materials, qualities and techniques

To mis-quote a classic 1980s pop song lyric: ‘It ‘aint what you use it’s the way that you use it’.

Even quite ordinary art materials can be used in different ways to create very different effects. Artists often experiment with the qualities of materials, pushing them to the limits of what they can do.

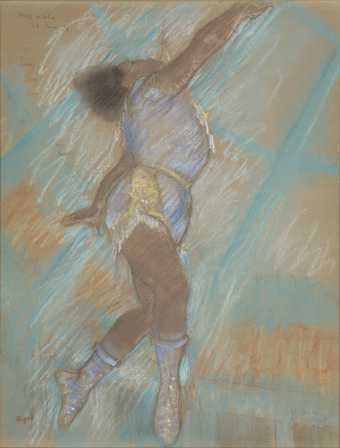

Washes, splats and layers: paint and what it can do

You may think that paint is a pretty standard art material. But how artists use paint is anything but standard. Paint can be so thin that it is almost not there – or so thick it looks three dimensional.

J.M.W. Turner is well known for his painted landscapes. But he pushed what he could do with paint so far that often his gestural washes and marks look abstract. Compare this watercolour painting by Turner with a watercolour by William Henry Hunt. Turner has used washy, messy broad strokes of paint to create a very real sense of a stormy sea and sky. The main subject of the painting, Bamburgh Castle, is hardly visible. While Hunt has used watercolour to create minute details of his natural scene.

William Henry Hunt

Primroses and Bird’s Nest

Tate

Turner enjoyed experimenting with the qualities of paint, but he usually depicted real places or recognisable scenes. Many artists, such as abstract expressionist painters, explored the quality of paint for what it is. They dripped, smeared and poured paint onto canvases, exploring its liquidity and colour.

Artist Niki de Saint Phalle took expressive mark-making a step further – firing a gun at bags of paint suspended against a white surface. In this video curator Kyla McDonald discusses de St Phalle’s shooting pictures as well as some of the other unusual materials and process she used.

As well as experimenting with what paint can do, artists have also explored the qualities of canvas, the surface that painters often paint on. Artists Angela de la Cruz and Sam Gilliam took the canvas off its square or rectangular frame creating three dimensional paintings.

To make Simmering 1970, Sam Gilliam spread a canvas out on the floor and covered it with diluted acrylic paint in layers so colours mixed together within the fibres of the canvas. He then suspended the canvas from a wall and applied drips and splashes of thicker paint. The resulting painting, released from a traditional square or rectangular format, hangs in folds from the wall. The work was, he explained, an attempt to ‘deal with the canvas as material … using it as a more tactile way of painting.’

Sam Gilliam

Simmering

(1970)

Tate

By removing her painted canvases from the square frames they are attached to, Angela de la Cruz creates striking artworks that combine formal tension with a deeper emotional presence. In this video, made when she was nominated for the Turner Prize in 2010, she talks about the materials she uses and how she manipulates them.

This film file is broken and is being removed. Sorry for any inconvenience this causes.

The rough with the smooth

Look at these sculptures. They are both made from stone but the artists have carved the stone in different ways to create very different results. How do the different surfaces affect how you respond to the works?

Dame Barbara Hepworth

Oval Sculpture (No. 2)

(1943, cast 1958)

Tate

Barry Flanagan

a nose in repose

(1977–9)

Tate

The smooth surface of Barbara Hepworth's head-like abstract sculpture, looks a little like a pebble or shell. Hepworth lived by the sea in Cornwall and the natural forms of the Cornish landscape influenced her work. Barry Flanagan seems hardly to have carved the stone for his sculpture at all. Apart from the light grooves he has added to the stone's surface, he has pretty much left the rough stone as he found it. Flanagan said that he wants the stone to reveal its own 'geography'.

Andrew Lord

biting

(1996–8)

Tate

Caroline Achaintre Mola 2014 © the artist

Caroline Achaintre and Andrew Lord also like to let their materials do the talking. Lord uses clay to create what he calls ‘process sculptures’. The bumpy surface reflects the gestures he has used to squeeze and mould the clay into shape. Achaintre also makes use of the maleable properties of clay. The clay in Mola folds into soft forms, its soft surface indented with the imprint of a snake pattern.

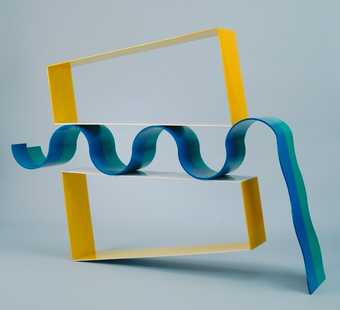

Material Tricks

Jeff Koons

Caterpillar (with chains)

(2002)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

Rather than playing with the qualities of materials, artists Claes Oldenburg, Jeff Koons and Fischli and Weiss play with our preconceptions about what things are made from.

Claes Oldenburg’s sculpture of a drainpipe isn’t straight and vertical as we expect drainpipes to be. Instead it sags and hangs. By making the structure from a soft fabric he messes with our understanding of materials and makes us question what it is we are looking at.

Claes Oldenburg

Soft Drainpipe - Blue (Cool) Version

(1967)

Tate

Jeff Koons also tricks us. His enormous sculptures of inflatable toys, such as Caterpillar (with chains) 2002 look like scaled-up versions of the actual thing. They look light and full of air with a bouncy surface. But in fact they are cast from metal cleverly painted to look like plastic vinyl. So they are in fact vey heavy with a hard cold surface.

Artists Fischli and Weiss also play with our perception of materials and objects. Untitled (Tate) 1992-2000 looks like a room – possibly a studio or workshop – full of various objects. The objects are familiar, everyday things: tools and materials, plastic buckets, paintbrushes, rubber tyres, furniture and small items such as milk cartons and cigarette packets. But everything you see in this room has been carved from polyurethane foam and painted to look like the real thing.

Peter Fischli, David Weiss

Untitled (Tate)

(1992–2000)

Tate

© Peter Fischli and the estate of David Weiss, courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery, New York

The properties of materials – their liquidity, weight, surface etc – were manipulated by Fischli and Weiss to create a mesmerizing, chain reaction, kinetic sculpture called The Way things Go.

The everyday, the Unusual – and the Unpredictable

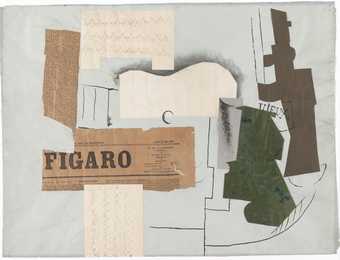

Increasingly over the last hundred years, artists have challenged the idea that certain materials are unsuitable for art.

At the beginning of the twentieth artists began to use materials not normally thought of as art materials. Cubist artists Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, added scraps of newspaper or the labels from bottles to their paintings. As well as playing with what is real and what is depicted in paint, this collaging of different things onto the surface of a painting added texture to the work.

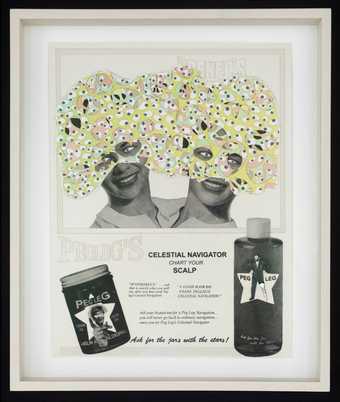

Contemporary artists Ellen Gallagher and Wangechi Mutu make rich layered collages from found images in newspapers and magazines that explore themes including self-image, the representation of women and history.

Pablo Picasso

Bottle of Vieux Marc, Glass, Guitar and Newspaper

(1913)

Tate

Ellen Gallagher, from Deluxe 2004-5 © Ellen Gallagher

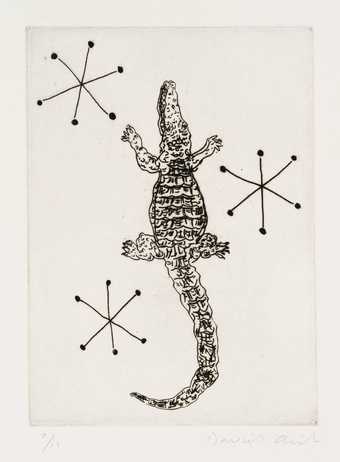

Assemblage is a term used to describe three dimensional collages – artworks made from objects added together. Kurt Schwitters, after making richly textured collages from scraps of paper began to add objects into his work. Artists such as Eileen Agar used unusual ‘found’ materials to make her sculptures such as shells, feathers and bits of cloth.

The art of everyday

Lots of artists in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries have used everyday objects in their art to explore aspects of society and culture.

Marcel Duchamp presented ordinary manufactured objects – such as a bicycle wheel, a bottle rack and even a urinal – as art. By taking the object away from its functional use it makes us look at the object in a new light, giving it a new meaning. Duchamp used the term 'readymade' to describe these artworks. Surrealist artists often juxtaposed two very different objects to create unsettling artworks.

Marcel Duchamp

Why Not Sneeze Rose Sélavy?

(1921, replica 1964)

Tate

© Succession Marcel Duchamp/ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2024

Man Ray

Indestructible Object

(1923, remade 1933, editioned replica 1965)

Tate

Salvador Dalí

Lobster Telephone

(1938)

Tate

© Salvador Dali, Gala-Salvador Dali Foundation/DACS, London 2024

Contemporary artist Helen Marten brings together a range of handmade and found objects (including cotton buds, coins, shoe soles, limes, marbles, eggs, snooker chalk and snakeskin). Her playful, collage-like gatherings of objects and images create poetic visual puzzles that seem to invite us into a game or riddle. The intricate details of her installations encourage us to look closely at the objects and materials she uses and think about the things we surround ourselves with in the modern world.

Watch Helen Marten talking about her approach to materials.

This film file is broken and is being removed. Sorry for any inconvenience this causes.

The cheap and the throwaway

In the 1960s, artists such as Carl Andre, Dan Flavin and Charlotte Posenenske used basic materials associated more with house building than art to make their sculptures. They hoped that by deliberately avoiding established art materials, they could sidestep the increasing commercialisation of the art world. (Also, these materials – bricks, tiles, fluorescent lights and galvansied steel – were much cheaper for these struggling young artists!).

Dan Flavin

“monument” for V. Tatlin

(1964)

ARTIST ROOMS

Tate and National Galleries of Scotland. Lent by the Estate of Dan Flavin 2013

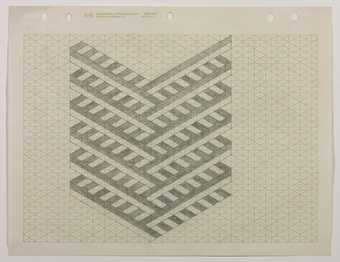

Charlotte Posenenske

Square Tubes [Series D]

(1967)

Tate

© Estate of Charlotte Posenenske/Burkhard Brunn, Frankfurt/M.

Artists belonging to the Arte Povera art movement also used unusual materials to challenge and disrupt the values of the commercialised contemporary gallery system. Arte povera means literally ‘poor art’ and refers to the artists’ exploration of a wide range of materials including soil, rags and twigs and coffee beans.

Marisa Merz

Untitled (Little shoe)

(1968)

Tate

Jannis Kounellis

Untitled

(1969)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

Victor Grippo

Energy of a Potato (or Untitled or Energy)

(1972)

Tate

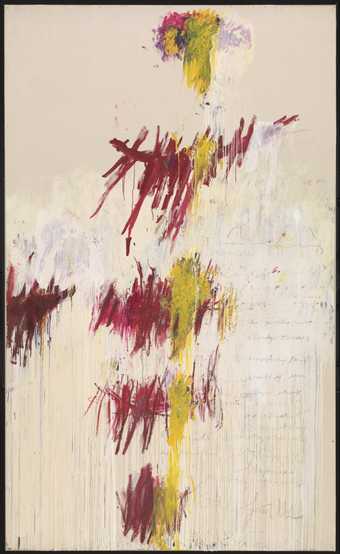

Anya Gallaccio makes installations from chocolate, flowers and other organic materials. She is interested in exploring the natural processes of transformation and decay. Gallaccio is unable to predict what state the materials will be in at the end of her installations. Something which at the start of an exhibition may be pleasurable, such as the scent of flowers, inevitably becomes increasingly unpleasant over time.

Anya Gallaccio

preserve ‘beauty’

(1991–2003)

Tate

© Anya Gallaccio. Courtesy the artist and Thomas Dane Gallery.

Nature into Art

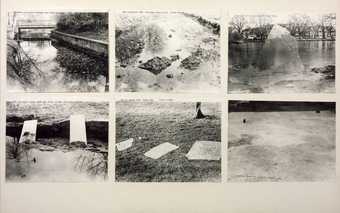

Bruce McLean

Six Sculptures

(1967–8)

Tate

Richard Long CBE

Waterfall Line

(2000)

Tate

The temporary nature and undpredictible quality of materials is also something that Bruce McLean and Richard Long have explored in artworks made from natural onjects and materials. Over one year Bruce McLean made six sculptures from natural materials. He returned them to the environment and photographed them. The sculptures demonstrate McLean’s interest in time and its passing. With Floataway Sculpture, the water currents break up the sculpture, transforming the piece into an event. Land artist Richard Long used materials found in the landscape, and sometimes even used the landscape itself, to make artworks. Waterfall Line 2000 is made from mud thrown at the wall and smeared and scrubbed away by the artist.

Physicality, surface, texture, colour

To me, that sort of physical engulfment or absorption in the materials world is actually the most complete freedom that can be felt

Karla Black

Karla Black Opportunity for Girls 2006 courtesy private collection

For some artists the quality of the materials themselves is what makes the work. Artist Karla Black uses unlikely materials such as nail varnish, cellophane and bath salts alongside more established art materials to create what she calls her ‘loose material sculpture’. In this video she talks about using traditional materials alongside very untraditional ones such as nail varnish, shampoo and make-up.

Anish Kapoor covers abstract forms with intense, brightly coloured pigments. The sculptures suggest spirituality and the rich materials and dense colours create an immersive experience for the viewer. Ishi's Light 2003 seems to invite us to step inside its deep red glossy interior seems a place of security. But its glossiness reflects and distorts the image we see of ourselves.

Sir Anish Kapoor CBE RA

Ishi’s Light

(2003)

Tate

Sheila Hicks's sculptures and wall hangings are all about texture. The pieces are often vibrantly coloured and made from a diverse range of materials. Caroline Achaintre also makes richly textured textile pieces. The bright colours and cartoon-like shapes of Chin-Chin 2001 add an updated twist to traditional approaches to weaving.

Sheila Hicks

Quipu de Cobré

(1962)

Tate

Caroline Achaintre in her studio, June 2014. Photo © Victoria Siddle

Caroline Achaintre Chin-Chin 2011 Courtesy Arcade, London

Art from Nothing

From materials that are very present – with rich textures, surfaces and a strong physical presence – to materials that you can’t touch or grasp: sound, light, air and empty spaces have all been explored by artists.

Susan Philipsz uses sound recordings, mainly of her own singing voice, and projects these into spaces. Her voice is untrained and she leaves in her breaths and imperfections to create a sense of intimacy. She is interested in how sound can trigger memory and emotions and has reworked songs varying from traditional folk music and sixteenth century ballads to songs by Nirvana and David Bowie.

While each piece is unique, she explores familiar themes of loss, longing, hope and return.

Martin Creed's Work No. 210 Half the air in a given space consists of hundreds of balloons that visitors are invited to wander through. The balloons (which gradually deflate over time, are full of nothing but air, so although they are present in the gallery, they technically don't fill the space.

Martin Creed Work No. 200 Half the air in a given space

Rachel Whiteread House 1993 Photo: Sue Omerod © Rachel Whiteread

Rachel Whiteread often casts empty spaces – inside boxes, under furniture, around fittings, and even the inside of a house! We can't really see empty space, what we see are the physical things that define a space, such as the walls of a room or the sides of a box or wardrobe. So in a way she is giving physical form to nothing.

I simply found a wardrobe ... I stripped the interior ... turned it on its back, drilled some holes in the doors and filled it with plaster until it overflowed.

Rachel Whiteread

Watch this video and find out how to cast like Whiteread:

This film file is broken and is being removed. Sorry for any inconvenience this causes.

Materials and Symbolism

Some artists choose materials because of their symbolic significance. Behold 2009 is a a huge installation by Indian artist Sheela Gowda. It is made from two very different materials. Can you see what they are?

Sheela Gowda

Behold

(2009)

Tate

Behold is made from steel car bumpers and knotted human hair. Gowda used roughly 4000 metres of twisted hair, meshing them into squiggly forms so the whole thing looks a bit like an abstract, three-dimensional drawing. The work was inspired by talismans (or good-luck charms) made from human hair that are knotted around car bumpers in India to protect against bad luck. Gowda has also used other unusual materials to symbolise aspects of Indian culture and belief including spices, plastic sheeting – and cow poo! In India cow dung is respected because it has lots of valuable uses, from fertilizer to medicine so is something that gives and preserves life (as it makes things grow and helps people who are ill).

Artist Khader Attia also uses an unlikely material that has a cultural symbolism. Although Attia grew up in Paris, his parents were Algerian. Untitled (Ghardaïa) 2009 is a scale model of the ancient city Ghardaïa in the M’zab Valley in Algeria. The model is made from cooked couscous, a staple food of North Africa.

It’s not really about the material – it’s about our capacity to shape things

Theaster Gates

African American artist Theaster Gates uses a range of recycled materials. He often uses materials in a symbolic way, addressing aspects of black culture and history in America. Civil Tapestry 4 2011 is made from old fire hoses. The hoses symbolise a horrific event that took place in Alabama in 1963. Young black school children were marching peacefully to demonstrate for equal rights. Police used powerful fire hoses to break up the march, injuring many of the young protestors. Gates has arranged strips of decommissioned fire hoses to resemble the composition of a 1960s American abstract painting – a period in art that pointedly failed to engage with the Civil Rights movement.