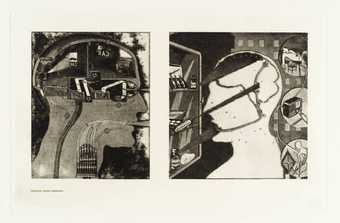

Sir Eduardo Paolozzi

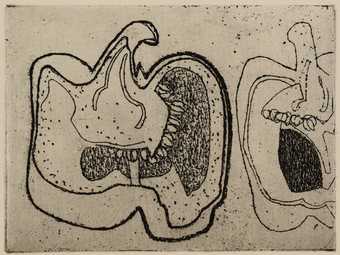

Secrets of Life - The Human Machine and How it Works: Perception through Impression

(1970)

Tate

What are senses?

We tend to learn we have five senses in Primary school – hearing, sight, taste, smell and touch. But there are actually lots of ways that we take inputs from the external world, ready for processing. We sense heat and pain, we have a sense of balance and know if we’re moving, we know where our body parts are in space without seeing them. We also have some other sensory experiences – can you tell if someone is looking at you even if your face is turned away? Is there a distinction between senses and sensations: maybe feeling hungry or thirsty is a sensation? Artists often translate senses from one to another to ask questions or try to make sense of it.

Touch

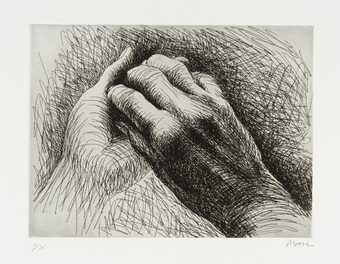

Hand

When we think of touch, we might first think of our hands. Our hands have the most sensitivity to pain, and have very precise nerve endings which help us perform fine motor tasks with our fingers.

Donald Rodney

In the House of My Father

(1996–7)

Tate

In the House of My Father is a close-up photograph of British artist Donald Rodney’s hand, holding a tiny sculpture of a house held together with pins. The sculpture is a separate work titled My Mother. My Father. My Sister. My Brother 1996-7, and was made from pieces of Rodney’s own skin, taken from one of the many operations had to combat sickle cell anaemia, an inherited blood condition. Both works together address Rodney’s sense of family and identity, as a British-born artist whose parents had emigrated from Jamaica, as well as relating to his own illness and mortality.

Have you ever run your hand along railings or a fence? Do you remember the satisfying thunk, thunk, thunk and the bouncing feeling in your arm? Belgian-born artist Francis Alÿs walked around squares and streets in London trailing a wooden drumstick along the railings in front of the houses. Alÿs took drumming lessons before making this work, looking to find the rhythms of the city. But watching this video, it is not just the sound that is evocative, but his action also reminds us of how it feels to bump a stick along a fence.

Francis Alÿs

Railings

(2004)

Tate

Don’t Touch is one of the most familiar instructions in a gallery setting. But some artists make works that are made for touching.

Rudolf Stingel

Untitled

(1993)

Tate

Rudolf Stingel created an artwork consisting of a wall 5.2 metres high and 9 metres long entirely covered with thick orange carpet. Its thick pile means you can rub the carpet up one way or smooth it down the other way. This means you can also write or draw patterns in the carpet, or erase other people’s marks. The sensory tactile experience of making the marks is as much a part of the work as the visual experience of the huge expanse of orange and the marks left in it.

If you can’t touch an artwork, it can often look like it has been touched by someone. Antony Gormley’s bed is made from 8640 slices of Mother's Pride white sliced bread. He bit into (and ate) some of the slices to create a double imprint of his own body in the stacks of bread. He then dried each slice and dipped them in paraffin wax to slow down the decay process. Can you imagine the feel of the body imprinted in the bread, sinking in to the pillowy dough? Or can you imagine the sensation of biting into all those slices of bread?

Sir Antony Gormley OBE RA

Bed

(1980–1)

Tate

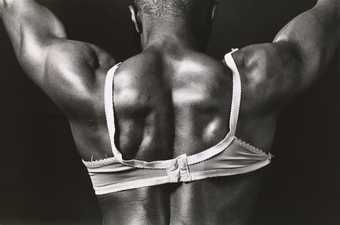

Skin and flesh

The skin is our largest organ of sense - thousands of nerve endings receiving all sorts of information: pressure, pain, temperature, weight and grip. Many artists have tried to present flesh and skin in a way that we can recognise as soft, wrinkled or weighty, using paint, and sculptural materials.

Helen Chadwick

Enfleshings I

(1989)

Tate

Ajamu

Body Builder in Bra

(1990)

Tate

Euan Uglow

Nude

(1962–3)

Tate

Marc Quinn

No Visible Means of Escape IV

(1996)

Tate

John Coplans

Self-Portrait (Torso, Front)

(1984)

Tate

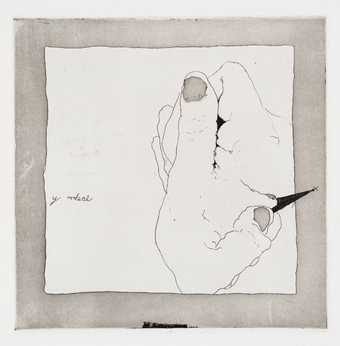

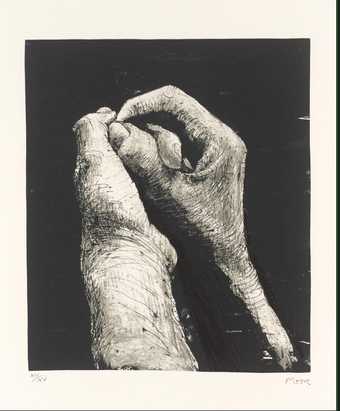

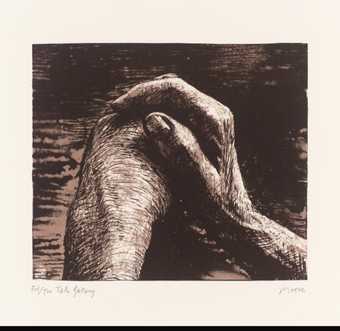

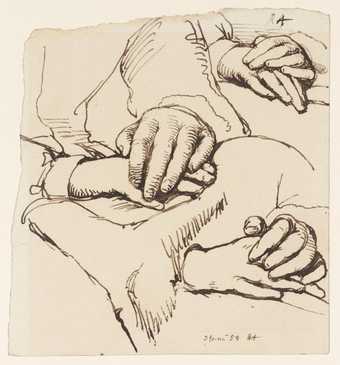

Giuseppe Penone

Study for ‘Breath of Clay’

(1978)

Tate

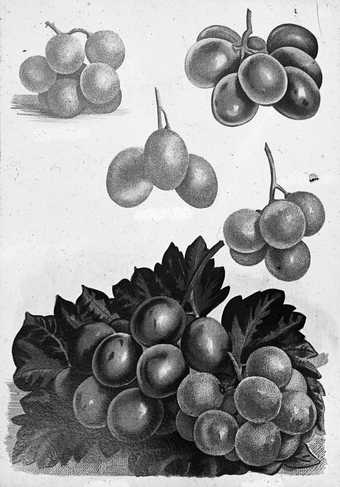

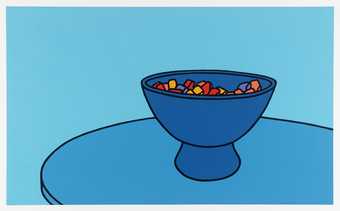

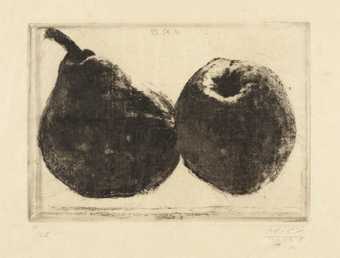

Taste

Can you taste an artwork?

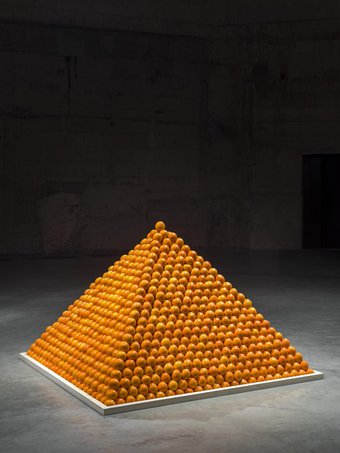

Roelof Louw’s Soul City (Pyramid of Oranges) begins its exhibition as a pyramid made from about 5800 oranges. They are stacked up as if they were in a giant market stall display. Visitors are invited to take an orange, gradually consuming the work. Even if no one takes them, the work will still eventually rot.

Roelof Louw

Soul City (Pyramid of Oranges)

(1967)

Tate

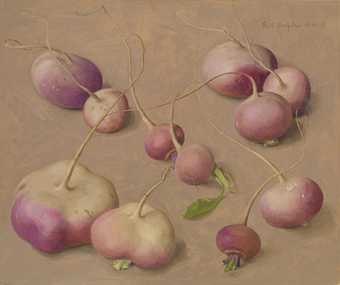

Is it possible to conjure up a taste sensation just by looking at something? Some images can evoke such a strong association, they might even get our mouths watering...

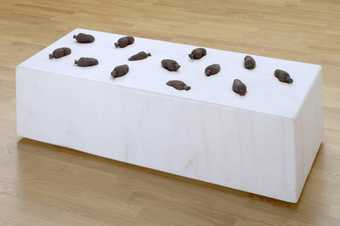

Andrew Lord’s biting is a set of teapots made by biting the clay to create the form. The marks not only remind us of the sensation of biting into the soft clay, but also of the likely muddy taste or the gritty feeling between your teeth Lord has said that using different parts of his body as a tool ‘became a way of identifying and isolating senses and sensations and a way to assemble a catalogue of my physical self, a record of my physical memory.’

Andrew Lord

biting

(1996–8)

Tate

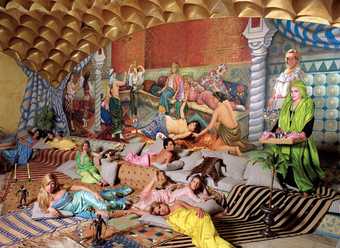

What else do we call taste? Bad taste often applies to unfashionable ideas about home decoration or clothes, or a joke or standpoint that feels out of step with everyone else.

Daniela Rossell’s large photographic print belongs to the series Rich and Famous which depicts members of the wealthy Mexican ruling class. Most of the photographs show the wives and daughters of the elite in palatial houses and apartments that show off their occupants’ opulent lifestyles and kitsch taste. Many of the sitters are Rosssell’s friends and acquaintances, and the series can be read as a comment on a pampered group in a country where poverty is rife.

Daniela Rossell

Untitled

(2002)

Tate

Smell

Jannis Kounellis

Untitled

(1969)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

Untitled 1969 by Jannis Kounellis consists of seven burlap sacks, each filled with a different pulse or bean: chickpeas, coffee beans, green lentils, green peas, kidney beans, white beans and maize. The top of each sack is rolled back so that the contents can be seen. By taking these everyday ingredients into the gallery, Kounellis invites us to experience them on a sensory level. When the work was originally displayed in Germany in 1969, visitors could smell the aroma of the coffee beans and, reportedly, also took handfuls of grain and either threw them on the gallery floor or chewed them whilst walking around the exhibition.

Vong Phaophanit also used a staple food stuff in his work Neon Rice Field 1993. Seven tons of dry, white long-grain rice are laid on the floor, with six parallel tubes of red neon light laid under the undulating waves he creates. The light glows through the translucent rice. As well as its visual impact, the rice also generates its own particular smell, which pervades the gallery space.

When Sculptor Veronica Ryan had a residency at Tate St Ives in Cornwall, she made new work responding to another sculptor, Barbara Hepworth. Working in Hepworth’s old studio, she found Cornwall reminded her of the Caribbean island of Montserrat, where she was born and had lived until her family emigrated to the United Kingdom when she was one and a half years old. Is memory a sense?

One of the works she made there was Quoit Montserrat . It is a large piece of marble with rubber soursop fruit set on the top. These fruit are symbols of Montserrat for Ryan, who has said that her childhood memories of living there are mostly linked to sensory experiences like tasting new fruit. She recalls tasting soursop for the first time when her family briefly returned to Montserrat in the mid-1960s, and describes soursop as having a perfume that is ‘so pungent it is both sweet and sour.’

Veronica Ryan OBE

Quoit Montserrat

(1998)

Tate

Hearing & Sound & Voice

Many artists work with sound as their medium. Some sound performances live on only as a record of what was performed, while others are recorded and replayed.

Fikret Atay’s video piece Rebels of the Dance shows two boys singing and dancing in a small shop or bank lobby with a cash point. The boys sing in harmony, following each other’s leads as they shift from one rhythmic tune to another, in traditional festive Kurdish dance music. The video was filmed in Atay’s home town of Batman in the Kurdish region of Turkey close to the Iraqi border. Years of political oppression and military intervention have left the city poverty-stricken. Kurdish communities have often been oppressed and have relied on music to communicate cultural traditions and political dissent. In Turkey, Kurdish music was banned for much of the twentieth century, perhaps giving the boys’ concert a more dangerous quality of rebellion than the prank it might seem to other eyes.

Fikret Atay

Rebels of the Dance

(2002)

Tate

Can you paint a sound?

Jack Smith

Sounds and Silences (to the Left of Red)

(1975)

Tate

‘I think of my paintings as diagrams of an experience of sensation. The subject is very important. The sound of the subject, its noise or its silence, its intervals and its activity. When I talk about the sound or the music of the subject, I'm not always thinking in terms of a symphony, but groups of single notes. The closer the painting is to a diagram or graph, the nearer it is to my intention. I like every mark to establish a fact in the most precise, economical way.’

Sight & Light

When we think about art, we tend to think of it as a visual medium. Sight is our bodies registering light and our brains making sense of that based on what we know about the world, and some artists have worked directly with light.

In West Ham – Sculpture for Football Songs Angela Bulloch uses Belisha beacons (the orange lights that signal a pedestrian crossing), taken out of their context and therefore changing their meaning. These beacons blink claret and blue, the colours of the kit worn by players for West Ham Football Club. This work is activated by the presence of gallery visitors. There’s a microphone in the gallery that detects sound and determines how long the lights switch on for. Bulloch sees the viewer as an active participant in co-producing her works, saying:

The viewer is a collaborator in the sense that she defines, perceives the meaning in her own terms. This would happen anyway with any work, provided there is a viewer. What I try to do is make the fact of interpretation, understanding or perceiving part of the purpose of the work itself.

Angela Bulloch

West Ham - Sculpture for Football Songs

(1998)

Tate

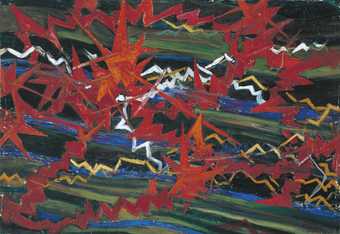

Sometimes a sensory experience takes you over, and all you can do is paint how you feel.

Gerardo Dottori

Explosion of Red on Green

(1910)

Tate

'I did not know how to paint this and returned home with a vivid impression, with the sensation of the interaction of these two complementary colours, red and green, when they are found together: red, when it meets its complementary, green, becomes ultra-red and explodes... green, on the other hand, remains calm, silent and immobile.'