Susan Hiller’s intervention At the Freud Museum 1994 (fig.1), the first incarnation of From the Freud Museum 1991–6 (Tate T07438; fig.2), interrogated the Freud Museum in London, Freud’s collection of antiquities, and his understanding of archaeology within psychoanalysis.1 It did so by asking both personal and epistemological questions: When did Freud begin collecting antiquities? What type of collector was he? How did he display his collection? What is the relationship between these historical objects that manifest the past and Freud’s interest in archaeology as a metaphor for the psychoanalytic practice of excavating personal history? What can archaeology offer psychoanalysis and what are the limits of this relationship? It is with this final question that a slippage takes place from Freud’s interest in the archaeology of objects, as manifest in his collection, to the metaphoric use of archaeology within psychoanalysis. By considering Freud’s various interests in archaeology in light of Hiller’s installation At the Freud Museum, we will see that what began as an archaeology of the mind for him, and an archaeological practice for Hiller, in the end turns into a not-archaeology: a challenge to what archaeology can offer artistic practice and psychoanalysis.

Fig.1

Susan Hiller

At the Freud Museum 1994

Installation view

Freud Museum, London

© Susan Hiller

Fig.2

Susan Hiller

From the Freud Museum 1991–6

Glass, 50 cardboard boxes, paper, video, slide, light bulbs and other materials

Displayed: 2200 x 10000 x 600 mm

Tate T07438

© Susan Hiller

Photo © Tate

At the Freud Museum consisted of twenty-three archaeological boxes made up of seemingly worthless and meaningless objects and fragments – discards, rubbish, fakes and ruins.2 With resonances of human origins, whether mythological, geological, historical or from popular culture, the items also reflected moments of political turmoil and historical crisis. Hiller accrued these objects serendipitously during her extensive travels throughout Europe, North and South America, and Australasia. Although they were found through happenstance, Hiller has stated that they were chosen because they carried with them an ‘aura of memory’ and ‘hint[ed] at meaning something’.3 The prescient and distinctive nature of the objects was intended to appeal to our need to excavate, interpret and understand the past within the present.

Having At the Freud Museum inside the museum itself invoked Freud’s own practices as a collector and curator. Freud purchased his first sculptures – copies of Florentine statues – in December 1896, only two months after the death of his father. In a letter to his colleague and friend, the otolaryngologist Wilhelm Fleiss, he noted that the experience of acquiring these sculptures was for him ‘a source of extraordinary invigoration [Erquickung, also translated as comfort and renewal]’ during this difficult time of loss and mourning.4 The next time Freud referred to an acquisition of antiquities – rather than replicas – was in a postcard to his wife Martha in 1897, sent while he was travelling in the Italian lake town of Bolsena. It is quite likely that Freud was speaking of an Etruscan statuette. Then, on 20 August 1898, while taking a trip in Innsbruck, Freud wrote to Fleiss saying that his latest purchase was a Roman statuette of ‘an old child’.5 From this point onwards, Freud’s collection grew rapidly as he procured objects during his travels across Europe, acquiring them by befriending various dealers in Vienna, Berlin, Paris and Rome, and receiving them as gifts from his family, friends and colleagues. Often seeking advice and authentication from friends and experts in the field, Freud made many well-considered decisions.6 He also bought a few fakes, a few reproductions and some broken and damaged pieces simply because he wanted to have the objects near him. Freud often sold objects from his collection when he tired of them or required funds to obtain other pieces, and he delighted in gifting his antiquities to colleagues, friends and family.7

Fig.3

Photograph of Sigmund Freud’s desk showing statuettes, 2015

Freud Museum, London

© Freud Museum London

In her 1994 installation Hiller’s archaeological method of arranging and displaying an object or thing alongside a representation such as an image, text or chart and labelling it with a title raised questions about Freud’s own curatorial strategies. We know that Freud moved the objects around his study and consulting room, making new arrangements of them. When one of his patients, the American author and poet Hilda Doolittle (known as ‘H.D.’), found herself in the midst of this vast collection for the first time she noted that Freud was a ‘curator in a museum’ surrounded by his antiquities.8 Art historian and curator Jon Wood has suggested that ‘a number of curatorial tendencies can be discerned’ in the arrangement of objects on Freud’s desk (preserved in the Freud Museum’s display; see fig.3). Placed in rows facing him, the combination of scales in the statuettes and the use of pedestals turn some into ‘miniature monuments’ resulting in ‘a contradictory spatial and temporal experience of nearness and distance, small-scale and monumental’. In addition, there is what Wood calls an ‘active aesthetic’ at work in Freud’s display due to the varying heights, materials and finishes of the objects, and the ‘range of times, places and cultures’ within the collection of antiquities on Freud’s desk results in a ‘mini, desk-bound museum without walls’.9 Freud’s mini, desk-bound museum, situated within his larger collection, one that scholar of psychoanalysis John Forrester has called ‘a museum within a museum’, was echoed by Hiller’s mini-installations – the individual boxes of At the Freud Museum – within the larger intervention of the work as a whole.10

The importance of Hiller’s show was to demonstrate the close connection and the blurred boundaries between Freud’s antiquities as a material archaeological collection and his use of archaeology as a metaphor for psychoanalysis. We have already seen how the first was activated by Hiller’s installation; as for the second, it is useful to begin with Freud’s interest in archaeology.

Freud’s attraction to archaeology was in part due to its popularity in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Both archaeology and psychoanalysis emerged as fields of knowledge and practice during this time, and each did so with equal amounts of fanfare and infamy.11 For Freud, both the popularity of archaeology as a mode of encountering the past and the employment of the archaeological metaphor were meant to legitimise the scientific ambitions he had for psychoanalysis as a practice and as a way of understanding the formation of the human subject. The use of archaeology was to bring popularity and ‘respectability’ to psychoanalysis.12 Freud was knowledgeable about the contemporary world of archaeology – from Giuseppe Fiorelli’s excavation of Pompeii and Heinrich Schliemann’s Troy to Arthur Evans’s exploration and excavation of Knossos along with their accompanying controversies, George Herbert Carnarvon and Howard Carter’s discovery of Tutankhamen’s tomb, and Leonard Woolley’s excavations of Sumerian Ur. Freud hoped that by using archaeology as a metaphor within his work, the sense of archaeology’s innovation, popularity and scientific judgment would positively impact upon psychoanalytic theory and practice.13

Freud was so proud of his knowledge of archaeology and its embodiment in his antiquities that on 7 February 1931 he wrote a letter to his friend, the novelist, playwright, journalist and biographer Stefan Zweig, in which he made it clear that he felt slighted by Zweig’s recent essay on Freud in which there was no mention of his collection: ‘I have made many sacrifices for my collection of Greek, Roman, and Egyptian antiquities, and actually have read more archaeology than psychology’.14 Perhaps it was an exaggeration to say that he had read more archaeology than psychology, but Freud certainly had a serious and enduring interest in archaeology as a practice and as a metaphor for psychoanalysis and the formation of the human subject.15 As Forrester puts it, Freud had a ‘desire to be an archaeologist of the mind’.16

Yet by 1937, near the end of Freud’s life, the usefulness of the archaeological metaphor had reached its limit, as Freud outlined in an essay published that year titled ‘Constructions in Analysis’. For Freud it was now the psychoanalyst, not the archaeologist, who was able to reach impressive goals in his work, objectives that were impossible for the archaeologist to achieve.17 This was the result of the psychoanalyst having, as Freud explained, ‘more material at his command to assist him, since what he is dealing with is not something destroyed but something that is still alive’.18 This living material was vital to Freud’s understanding of psychoanalysis. For Freud, the work of psychoanalysis was to slowly and carefully uncover and ‘translate’ the still living topological traces of fragmented memory or ‘memory images’ within the subject’s memory ‘landscape’.19 The ‘translation’ of this memory landscape is crucial to psychoanalysis. As Freud explained and emphasised, memory traces have undergone ‘from time to time a rearrangement in accordance with fresh circumstances – to a retranscription’. This means that they are in a constant process of reconfiguration. If a later retranscription does not exist, the earlier trace remains and becomes an ‘anachronism’ – what Freud called being in the ‘presence of “survivals”’. This is clearly a very dynamic understanding of the mind.20 Crucially, this also meant that the purpose of psychoanalysis was opposed to that of archaeology. Whereas archaeology endeavoured to hold still the excavated fragments so as to configure a total knowledge of the past, psychoanalysis recognised this impossibility. This is why art historian Whitney Davis has called psychoanalysis a ‘not-archaeology’.21 Psychoanalysis is a process of translating, deciphering and piecing together the ever-changing fragments and images from our past. In psychoanalysis we undertake this archaeological labour knowing that the process will never offer us a totality of any kind, nor would we aspire to achieving one.

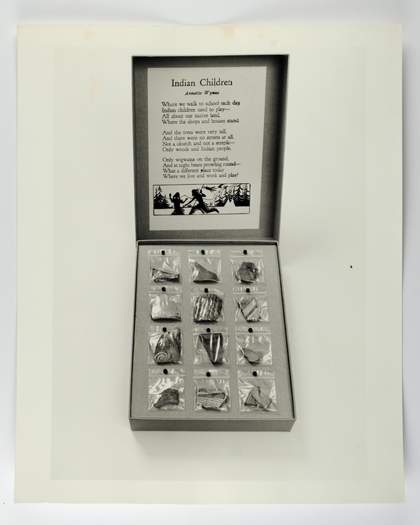

Fig.4

Susan Hiller

From the Freud Museum, box 010 A’ shiwi/native (boxed, 1993)

© Susan Hiller

Hiller and Freud found, collected, organised, conserved and chose what was to be included in their collections; in both cases, a collection that was once private subsequently became public. Hiller’s installation was an index of historical and cultural beginnings and crises as embodied in objects that were no longer of any seeming use or value. For instance, in box 002 Eυχη/prayer (presented, 1996), Hiller has placed a schematic map of Greece above a group of pebbles that she picked up when she travelled to the cave at the bottom of the Mani peninsula, near Vathia, through which the ancient Greek hero Aeneas is said to have entered the Underworld; in box 010 A’ shiwi/native (boxed, 1993) (fig.4), we find Native American potsherds in polythene bags, alongside a photocopy of a poem from an American primary school book about the former presence of Native American children on the land now occupied by US towns and cities.

As for Freud, it is helpful to turn to the work of psychoanalyst Adam Phillips, specifically when he informs us that through Freud’s collection and work, ‘[t]he Enlightenment Freud wants to tell us what we have in common; [but] the post-Freudian Freud, his collaborative antagonist, is the connoisseur of anomalies’.22 For Hiller, nothing but the structure of each box was consistent; all that they contained were serendipitous objects that later, through an archaeological method, came to have meaning. In light of this artistic intervention, and Phillips’s provocation, perhaps Freud’s collection may be understood, on the one hand, as an archive of our commonalities discovered through Western culture’s celebration (and often through its colonisation) of the ancient world’s achievements which, buried and revealed, enabled Freud to understand the human subject and the practice of psychoanalysis.23 On the other hand, the collection is also a compilation of ‘anomalies’ that like Hiller’s work did not provide us with a linear teleology of cultural and historical progression.24 As art historian Jack J. Spector notes:

The guiding principle by which Freud put his collection together was personal taste rather than any systematic interest in the objects. This becomes clear not only from the almost random heaps of objects, but from the surprising gaps and jumps from period to period and culture to culture; indeed, one’s first impression is that these objects have in common only their apparent great age and the remoteness of their origins … While Freud knew the value and background of most of his pieces, he was not driven by a narrow interest in one area, nor by the expert’s compulsion to gather all of the types in his special field.25

Freud’s unclassified, spontaneous, non-serial mode of collecting as a practice and process was personally motivated, his taste was eclectic and his enjoyment was private. Hiller’s At the Freud Museum, and the subsequent From the Freud Museum, shared this motivation. The mini-museums of both Freud and Hiller were each the result of the collector’s desire. Each of these two collections functioned as a museum of curiosities, rather than a ‘proper’ collection. Each materially manifested the individual collector’s understanding of culture and of collecting. Perhaps philosopher Jean Baudrillard was correct when he informed us that ‘it is invariably oneself that one collects’.26 Like the psychoanalytic process itself, and Hiller’s installation, these two individuals’ collecting habits were not about conferring authenticity upon the past, but about understanding our changing self in the present.