Tao Aimin

Image courtesy of the artist

Monica Merlin: Could you talk about your work Women’s River?

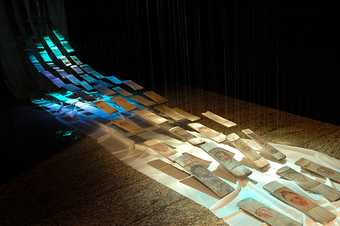

Tao Aimin: Women’s River was my first installation, made in 2005. I collected washboards one by one from the countryside, the streets and the places where city blends into countryside. In this work, there are altogether fifty-six washboards, upon which I painted the portraits of their owners. The process of collecting the washboards is like doing a performance piece – I took photographs of the owners and recorded the history of the washboards. I also chatted with the owners about their life stories. Through these conversations, we established an emotional connection and I was able to better understand their lives.

Monica Merlin: How did they react?

Tao Aimin: Since nobody had ever collected old washboards before, the typical reaction was surprise. They found it strange that I would want to collect these things. Nowadays washboards are rarely used in China, since everyone has a washing machine, but these women still fondly remember washing clothes with washboards and some of them actually still use washboards to wash small pieces of clothing. Perhaps because they believe that hand wash is cleaner.

Tao Aimin

Women’s River 2005

Image courtesy of the artist

Tao Aimin

Women’s River 2005

Image courtesy of the artist

When they asked me why I wanted to collect these washboards, I said that I wanted to paint on them and use them in my artwork. When they heard this, they were very supportive and some even gave me their washboards for free. Normally I bought them – they usually only cost a few yuan. In the beginning, I also swapped new ones for their old ones, which they were generally very happy to do. So through the process of collecting the washboards, I came to understand their owners and record things about them. I took photographs and asked the owners how long they had used the washboards for and whom they washed clothes for. I had the chance to meet many kind-hearted women through this process, who unconditionally dedicate their hard work for their families. When I brought the washboards back to my studio, I painted their owner’s portraits on them.

Originally, the washboards had clearly defined ridges on them, but as they were used to wash clothes over and over again, they got smoother and smoother until they became flat. The idea behind painting the women’s portraits on these washboards came from the sense of history in their wrinkled, time-worn faces: I thought they were really beautiful and painting them on the washboards added more lines and texture to the portraits.

This work is shaped like a river, because the washboards – used by many Chinese women over such a long time – fittingly represent the history of Chinese women. Since there were no washing machines in the past, every Chinese woman, whether she lived in the countryside or the city, would use a washboard to wash clothes for her family. Other objects, such as rolling pins or bowls, cannot express the sense of time as effectively as a washboard, which clearly shows the trace of time with its rubbed surface. Also, because everyone rubs in a different way, the washboards show individualised surfaces. Some people rub hard, so their boards are extremely flat; others do not rub as hard and their boards have more edges. One woman created a shape like a flower through her way of rubbing. I thought that she must be a really kind-hearted woman with a real Buddhist spirit to be able to create these lotus-like patterns.

I have collected washboards for many years now and the number has now reached a thousand. When I made them into my first work, I shaped them like a river not only to invoke a sense of history and time, but also to bring in the idea of women’s fate. As a Chinese saying goes, ‘women are like water, flowing and soft’: that is where the sense of fate comes in. Above the washboards, I installed a light that shines on the work and creates a water effect. The light constantly flows, while the washboards float above it. I also played the sound of a washing machine in the background, which links the piece to the present day.

Monica Merlin: Can I ask about the age and ethnicity of the women?

Tao Aimin: They are all different. Some of the women are from ethnic minorities and their ages range from thirty to ninety-nine. The oldest woman passed away at ninety-nine, though I first met her when she was ninety-three. I met her by chance: she was the owner of the first washboard that I collected and she lived in the artist’s village in which I was staying in. Later she became my landlord and I rented her workroom. Because I had a video camera when I was living with her, I documented her life from the time we met until she passed away at ninety-nine; I made many videos and documentaries about her. She was a perfect representation of the typical life of a traditional Chinese woman: she was born in 1911 in the Republican period; she had bound feet; and she used the same washboard for thirty years, a washboard that she gave to me to use in this project. As I made the installation of washboards, I also documented her life. I made another series of works about her in addition to the installation, which spanned a period of five or six years of her life.

The age and lifestyle of the women from whom I collected washboards were all very different. Some of the old women were very good to me after I chatted with them for a while and they would invite me to their home for dinner. The old woman whose life I documented even regarded me as a granddaughter, part of her family. So she was not overly self-conscious of the camera or restrained in any way when I filmed her: she was completely relaxed and free.

My second work was Classic of Women. I rolled the washboards up to resemble the bamboo strips that Chinese classics were originally written on – but on a larger scale. There is no painting in this work, just text: I wrote an explanation of the work on the reverse side of the washboards. The idea was that I would treat the patterns created by the rubbing traces on the washboards as a kind of abstract writing. The first Empress in Chinese history, Wu Zetian (624–705), requested that her memorial stele in Xi’an be left blank, without any epitaph. It is now known as the Wordless Stele. I treated these washboards as part of a ‘wordless classic’: it communicates through the abstract language documented on the washboards by women’s hands over long years of washing. When you look at this work, you feel that these women are speaking about their experiences and feelings through the abstract language they created. Everything is expressed in the lines and texture of the washboards.

Another work was made for an exhibit in the Long March Space, a small space in Beijing’s 798 Art District. It is a combination of installation, photography and video about the process of collecting the washboards. For the project, I became just like a rag-and-bone woman, going round with bags and a camera. These are all photos I took randomly of people chatting on the street and so on.

In this piece, Washed Relics, around 280 washboards are arranged in a set above a mirror. As the washboards have been immersed in water for many years, I think of them as a kind of relic that was found in the water. By installing them in a gallery, I turned them into relics, no longer mere washboards. There is in fact a whole variety of washboards. For example, there is a type of washboard with bottle caps attached that is a folk invention. After the washboards have been rubbed flat and are no longer suitable for washing, bottle tops are nailed in so that they can be used for washing again. I have not altered any washboard from their original condition, so there are all sorts. Some boards have a few words casually written on them, others have a strip of tyre rubber nailed on so they can be used for washing again.

Monica Merlin: Are the differences in the washboards related to the different places that they come from?

Tao Aimin: Yes. In some places they tend to use really large ones, while in other places they use smaller ones. I collected one from Shanghai with writing on it. Another one had a flower carved on it, like the type you see on moon cakes. So different regions, north and south, have different styles.

Monica Merlin: When you were searching for washboards, how did you find the women? Did you just look around places in the countryside?

Tao Aimin: When I got to a village and saw a group of old ladies chatting together, I simply went over and asked them if they had any washboards at home. Then I would tell them that I collected them and we would start chatting. Also, in some places in the countryside they do not close their doors, so I would just knock and go in to ask them if they had any washboards, just like a rag-and-bone woman! But obviously I did not actually look like one, which is why the women did not get suspicious and readily chatted with me. I always took the initiative, since they did not know what I was doing. They might have thought I was looking for furniture, antiques, paintings, or other things.

Monica Merlin: If they were not using these washboards any more, why did they still keep them?

Tao Aimin: Some women were still using them, while others had stopped using them and thrown them on the firewood pile, as a piece of wood for burning or cooking. In their eyes, an old washboard was just a piece of junk and there was nothing special about it.

Monica Merlin: Are your works the product of a long period of research, or did you collect some, make a work, then collect more and make another work?

Tao Aimin: Throughout the entire period that I was collecting washboards I was making works at the same time. As time went on I got different ideas, but I never stopped collecting washboards and gaining experience. I have stopped now though. I think that having made so many works with washboards, it is time to stop and think things over.

Like I said, once they are moved to the gallery space, they become reconceptualised – their rustic origin undergoes a transformation because of this new context.

Monica Merlin: Would younger women buy new washboards, or would they use ones that had been passed down from older women in their family?

Tao Aimin: Some had been passed down, but were no longer used and were just sitting around. Some women bought their own. If you use these washboards every day, then within a few years you will have rubbed it flat. I guess that one woman, if she were to wash clothes every day, would go through six or seven washboards over her lifetime. After all, once they have been rubbed smooth, you cannot wash clothes with them anymore, so you have to buy a new one. In the complex where I live, there is one woman who washes clothes very often and she can use up three washboards in a single year! She washes clothes like a madwoman! I made a video of her. Her feet and hands are pulling everywhere and she rubs the clothes very hard on the board… the ‘cha cha cha’ sound of her washing clothes is pleasant to listen to.

Monica Merlin: Have you incorporated this sound into your installations?

Tao Aimin: Yes, in a later work, The Secret Language of Women. It was shown in an exhibition of contemporary Chinese ink painting and later went on a long tour of Europe; at the moment it is at the Istanbul Biennale. In this work, I used the washboards to make books. The books are slightly bigger than the washboards and each book has thirty pages, with a print of a different washboard on each page. I printed all the books myself by hand and did all the pasting and binding by hand as well. I used a very fine calligraphy paper in a pinkish colour. I used a variety of different printing methods, including wet printing and dry printing. The most common method I used was rubbing, the one used in the Xi’an Forest of Steles. I also included handwritten calligraphy.

The comments on the margins of each page are written in vermilion ink in nüshu, a women’s script. It originated from Jiangyong County in my home province of Hunan. I went to Jiangyong for one year specifically to study this script. It is totally unique, this script exclusively for women and only the local women of the Yao minority who originate from Jiangyong can read it. Because Jiangyong is located on an island, in the past you needed a boat to reach it. The island is really beautiful and as soon as I arrived, I found a nüshu master. She was an old woman in her eighties and she let me stay with her. While I was there she sung nüshu songs to me and wrote nüshu for me.

Monica Merlin: Are there many people in China today researching nüshu? The history of the script is fascinating.

Tao Aimin: In 2008 there were some, but there aren’t so many now. Recently, the famous musician Tan Dun put on a performance of a nüshu dance at a theatre in Beijing. Tan Dun is from the Hunan, so he is quite local to Jiangyong. He performs nüshu through music; I explore it through art. So there are people from different fields making work related to nüshu. There are some who approach it through literature and calligraphy. I approach it from my own perspective.

The form of The Secret Language of Women originates from a type of nüshu writing in Jiangyong, known as the Third Day Missives. These books were given to a woman by her sisters three days after her wedding. The books were kept secret and would be either burned or placed in the woman’s coffin after she died, so not many have survived to the present day. I bought one that was written more recently. It is made out of cloth and in the middle of each text there is an Eight Trigram symbol from the Book of Changes. It also contains drawings, fables and auspicious symbols. I based the symbol in my work on one of their symbols. It is very rare to see a symbol like that in the middle of a written text – it is a unique local practice. The Eight Trigrams had an important influence on the culture in that area.

I wrote the notes in the margins using nüshu, which included poetry and songs about of women’s emotions and stories. I wrote out texts from some ‘third day books’ in gold. The eight washboards in the middle form the shape of the Eight Trigrams. In the middle of the installation, I played a video I had recorded of the hands of eight women while they were washing clothes – the video shows only their hands. When one woman finishes washing, the video moves to the next pair of hands. There are young hands and old hands, all kinds of hands. There is sound as well, the sound of washing clothes. This installation incorporates elements of ink painting, video and calligraphy. This is the last installation I did with washboards.

So why did I combine the Jiangyong nüshu with washboards? Because I think that Jiangyong nüshu is a language just as the washboards are a type of language – they both tell stories. My work combines these two languages, because I feel close to both languages. I have been working with washboards for a long time now and as I come from Hunan the Jiangyong nüshu is part of my local culture. However, in my work I mainly focused on the language of the washboards; nüshu is something I felt comfortable to borrow and add in.

Later on, I made an installation of a series of ink paintings, High Mountains and Flowing Water. The paintings in this installation are very large and I painted them using the ‘splashed ink’ technique. It combines ink painting and washboards, which creates a variety of changes and a sense of natural flow.

Monica Merlin: Were these painted using the washboards?

Tao Aimin: These were all printed using washboards. I did not use my hands. I just let the ink run down by itself. The ink is mixed with other materials too, so it has a natural texture. These ink paintings embody something quite different from the traditional style of Chinese literati ink paintings, since they are very contemporary.

Monica Merlin: And all the traditional literati painters would have been men, so they perhaps were not that interested in women’s history.

Tao Aimin: Yes. I suppose I have elevated the washboards to give them the status of traditional Chinese literati ink paintings. Yet, I did not use a brush as the literati painters did. Instead, I used the contemporary technique of block printing. But the works still embody the emotional space of the literati painters’ high mountains and flowing water.

The Language of Water series is also printed. The lines on the washboards are quite similar to ripples in water. All my works have something to do with water – the flowing ink I mentioned earlier also looks like ripples.

Monica Merlin: When does that work date from?

Tao Aimin: 2007. Around that time I had dedicated one to two years to ink painting. That work used pure ink. I really like ink paintings, I am Chinese after all and I really like working with ink.

Another series of works, called Women’s Journal, is from 2011. It is written in gold, in Nüshu and it also features chop seals. I used a wide range of different washboards in this work, which yielded lots of different textures. It is just a very casual recording of various things combined with printings of washboards. Through the materials used, the piece showcases a change in texture with the combination of washboards and ink painting.

Monica Merlin: Are these works large?

Tao Aimin: Not too large – they are sixty by sixty inches. Another work I made, In a Twinkle, is very long, about three metres. I came up with the title because the patterns of the washboards reminded me of fingerprints. The writing in this work is also nüshu.

Now this one has quite a different feeling and different artistic conception as it contains a rich range of materials including colours and paints. It creates the feeling of an ink landscape painting, but it was printed with the type of washboards that have bottle tops nailed on them.

Monica Merlin: Did you use normal paper?

Tao Aimin: I used rice paper. It looks a bit like the Dunhuang frescos because of its blurriness and the way it settles. It looks very worn out, but it also gives you a warm feeling. The contrast between emptiness and solidity hints at the long history of the Chinese culture.

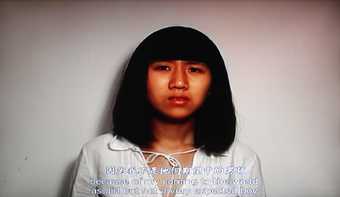

I took photographs of the old woman I stayed with for six years. I have also made a documentary video of the old woman. I recorded her daily life, things like the way she ate.

Monica Merlin: Why is the elderly woman naked in some of your photos?

Tao Aimin: The elderly in China have no gender. She is used to being naked and since she was hot she took her clothes off, even if her son was there. She often did not wear clothes. The photos were taken in my studio in the countryside near Changping, where we lived together. She was a Beijinger local and never left the area. She had tiny bound feet and lived in a traditional Beijing style courtyard house with a kang, which is a large brick bed under which a fire is lit in winter to for people to keep warm. Everyone who visited would go and lie on the kang, which took up half the room.

I remember a few years ago there was also another ninety year old woman, the same age as her, an 80eighty year old woman, her son, who was seventy and the carer too – I have not thought about them for a while. I made a documentary about her, called Lotus Fragments, about her life in the years before she passed away. Her children did not pay her a lot of attention and she would frequently fall over and have to crawl around. But I often went over to look after her and she would invite me to eat dumplings.

Monica Merlin: How was her health?

Tao Aimin: She was in relatively good health, but she was facing an increasingly nearing death and she spent a lot of time lying still in bed. I was really afraid for her because she had bound feet and could not walk very well, which is why she often fell over – one time she event cut her face.

Monica Merlin: Did she ever talk about her bound feet?

Tao Aimin: Yes, I recorded her talking about it. I have a thick diary all about her, as well as sound recordings, videos and photos of all the conversations we had. Her mother bound her feet when she was very young, as that was the custom at the time. Her foot binding was done with commitment, unlike another ninety-three year old woman that I met who took off her bindings and whose feet had returned to normal. The old woman I stayed with, however, carried on binding her feet. It was the first time I’d seen such pointed feet; they were completely deformed. She washed her feet every day, something that gave her great pleasure. While other people thought that she was in great pain, she had actually accepted the reality of her situation from very early on.

Monica Merlin: I think that today there are only very few women with bound feet, is that right?

Tao Aimin: Yes. That is why I wanted to document her, as she is part of a disappearing generation. But I think I am different from male artists, who just drop by a remote village, take photos of some old ladies with bound feet and then take off again. I explored the subject in far greater depth, as I lived with the old woman for six years and gained a comprehensive understanding of her life. Also, she was the person who owned the first washboard that I collected. Turning from the object to its owner, I documented her to represent the life of a woman who had used washboards. These are the two focuses in my art: washboards and their owners. The old woman is a perfect representation of this period of Chinese history. She had lived for 100 years, from the Republican period right through to the present day. She was a piece of living history.

Monica Merlin: What was her name?

Tao Aimin: She was called Wang Shuqing, but this was a name that other people had given her, she did not know her original name. She did not know her own birthday either. She experienced so much hardship because of her bound feet, it is simply incredible. What really moved me about her was the way in which she was so able to endure and persevere through it all. She did not have a great time in her old age. When she was doing housework she had to get a stool out in order to stand up. She would be shaking violently afterwards – without having been there yourself you just cannot imagine the scene. But she still cooked and did jobs at home, sewing clothes and blankets and so on. I made a short film of her threading a needle, which took her an hour, but she did not want any help. I offered to thread the needle for her, but she would not have any of it, even though her hands were trembling.

Monica Merlin: Did she talk a lot?

Tao Aimin: Sometimes she could not talk all that smoothly. The other old woman was much more of a talker. The short film I made of Wang Shuqing was shown in the US at a short film festival in January this year. I found her fascinating, much more than the other two old women I videotaped. They have all since passed away, including Wang Shuqing’s son.

Monica Merlin: Why did Shuqing’s son not care for her?

Tao Aimin: You need to watch the documentary. She had three properties. I lived in one and there was another one which she also rented out. There was a dispute over the properties – the lawsuit is still ongoing. Her estate still has not been divided up. The two brothers and the sister are still in court fighting over it to this day, but none of them ever wanted to care for the old woman. They just pushed her back and forth, even fighting about her. Fights over inheritance are a serious problem in the Chinese countryside nowadays, because houses have become expensive.

When the old woman died I visited the family. I was quite friendly with another son of hers, who is a good person. We often saw each other, since he did not live too far away. He was nice to me since I was good to his mother. I went to see her before she passed away and she was very thin and looked like a mummy. On Tomb Sweeping Day, I visited her tomb. She died two years ago, when she was ninety-nine. Nine is an auspicious number in China, it represents all things. A hundred years feels too far away and ninety-nine carries a great significance.

Monica Merlin: My grandmother died two months ago, she was eighty-nine – just a month off ninety.

Tao Aimin: That is a good long life. I think once people get to that age, their pain is replaced with a kind of completeness. Her son said of her that she was ‘ripe’, like a leaf ready to fall to the ground and turn to earth. Her skin was completely covered in wrinkles. When she was ill, she would often flit between the human world and the netherworld. During my time with her, I got to experience that feeling as well.

Monica Merlin: If you had not looked after her, would there have been anyone else to take care of her?

Tao Aimin: Her son employed a carer for her. But when the carer was not around there was no one. She still cooked for her son, who was over seventy.

Monica Merlin: Did she wear trousers?

Tao Aimin: Yes. Her feet were all wrapped up because they were bound and she wore special small shoes, which is why she often fell over.

Monica Merlin: Did she make the shoes herself?

Tao Aimin: Yes. You cannot buy them anymore – because nowadays no one pays any attention to these women, no one produces the shoes and socks for their bound feet any more. This is one of the reasons why I cared for old ladies like Shuqing is. There are still women in their seventies and eighties who have bound feet, but their generation will soon disappear completely. That is why this series is titled Swansong.

Monica Merlin: Can I ask how your interest in women’s history arose?

Tao Aimin: It came from my first washboard, which was one used by my mother-in-law. It was just lying around at home and I became interested in it. Before we got married, my husband’s mother would come to his home and help him wash his clothes using that washboard. Once we were married, she did not need to wash his clothes for him any longer. So that was the first washboard I found interesting and later on I collected Shuqing’s washboard, which was the first one I collected from someone else. That is how it started.

I think I am drawn to these old objects because I am from Hunan. Do you know what women in China used before washboards? They used poles, a bit like a rolling pin. I have also collected several hundred of those. I have not made these into artworks though. They are round and very smooth and they get smoother the more you wash with them. I sometimes think that they would be a good offensive weapon – you could beat people with them! People began to use them for washing clothes back in the Tang dynasty (618–907). The great poet Li Bai describes them being used for washing clothes in some of his poems.

Monica Merlin: Have you ever tried using a washboard?

Tao Aimin: Actually, I think there is a very deep-rooted reason why I used washboards in my art. My mother was a woman who gave everything for her family, washing all the clothes for her children. I used to love wearing white trousers, but kept getting them dirty. She would always wash them for me. Now, she babysits my brother’s children, her grandchildren. She comes from a generation of women who are completely unable to liberate themselves from their families. She feels like she should do her family’s laundry for them; she does not feel like she should go and enjoy life for herself.

I often have her over to stay with me in Beijing, hoping to let her enjoy freedom from housework. But she absolutely insists on doing all sorts of jobs. She does not have much authority in our family, as my father is something of a male chauvinist and holds the ultimate power. She is a completely traditional woman, working hard for her family and enduring my father’s bad temper.

I have no way to save her, to liberate her from this situation. It is really difficult, because she is set in her ideas. She will not liberate herself; instead, she wants to do all these jobs. Her hands are all deformed now from many years of washing clothes in cold water and she is not in good health, Also, she is really thin, having spent her whole life and all the vitality of her youth on housework – she was really beautiful when she was young, but now she looks old and tired.

She has gone back to Hunan now. Recently, she stayed with me in Beijing for a while, but she misses my brother’s children. She feels like she has to take on her duties as a grandmother. Personally, I feel somewhat constrained, since I cannot help her live like an independent woman and enjoy life. So these artworks actually come from my family background, my feelings of helplessness towards my mother. The works all express a feeling of tragedy and the heavy weight of history.

I do not wash clothes by hand – I have a washing machine. I think it washes very well actually. I do not want to criticise the way it was done in the past, but women in the past lived in a very different way from today. Wang Shuqing and other old women who I have spoken with have described the way that they washed clothes back then. They would get together around the village well and wash their clothes. It sounded really nice – when they had finished they would take out snacks and chat and eat while the clothes were hung up to dry. It became a type of public space for them to chat in.

But in today’s society, everyone lives in their own homes and this type of public space just doesn’t exist anymore. Everyone has washing machines and other mechanical aids. So it was actually quite a friendly time back then: there are two sides to it and you cannot only criticise. I want to record that era in my artworks and give people in the future more opportunities to see and understand the objects and people of the past. I hope that my works can elevate these washboards into the realm of history and culture. The US critic Maya Kóvskaya was so moved when she saw Women’s River that she cried. Since then, she has helped me with several overseas exhibitions. She once said that while these women have no names and have left nothing behind, I documented their fingerprints and, in doing so, my works commemorate their lives.

Monica Merlin interviewed Tao Aimin in Timezone 8 Café in 798 Art District, Beijing on 27 November 2013.