The symbol of the garden recurs throughout the cultures of the globe – from the various incarnations of the Garden of Eden in paintings, tapestries and literature across the Judaeo-Christian world, to formal Islamic gardens and their philosophical counterparts in the Far East, whether they be classical Chinese parklands or Zen landscape design. Gardens have also played a talismanic role in British culture, offering fertile imagery for art and literature across the centuries, and acting as a barometer for the country’s changing social and cultural landscape.

In Western iconography the image of the garden has been shaped and defined by the Biblical story of Adam and Eve, the original sinners thrown out of their paradise for tasting the forbidden fruit, and cast into the wilderness. It is surprising, however, how little description the Book of Genesis gives of the original garden:

The Lord God planted a garden in Eden, away

to the East, and there he put the man whom he had

formed. The Lord God made trees spring from

the ground, all trees pleasant to look at and good

for food; and in the middle of the garden he set

the tree of life and the tree of the knowledge of good and evil.

There was a river flowing from Eden to water the garden.

This rudimentary outline has given rise to many interpretations of the mythical garden, often depicted in early religious paintings as a rich, verdant orchard, full of flowers and trees. The imagery was enriched by the florid verses of the Song of Solomon, where the dialogue between bride and bridegroom is a contest of compliments using the metaphor of the garden. The bridegroom calls his love ‘an orchard full of rare fruits’, and uses the now well-known metaphor of his virginal bride as a secret garden: ‘My sister, my bride, is a garden close-locked, a fountain sealed.’

Sir Stanley Spencer

Zacharias and Elizabeth

(1913–14)

Tate

© Estate of Stanley Spencer. All Rights Reserved 2023 / Bridgeman Images

The ‘close-locked’ garden, or hortus conclusus, as it became known in the Renaissance, was one of the most influential early garden images. As a metaphor for virginity, as well as a reference to the prelapsarian paradise, it appears in many early religious paintings and tapestries. In works such as The Garden of Paradise c.1415 by the Master of Oberrheinische Kunst, the Virgin Mary sits safely with her companions in a garden with castellated walls; they read, pick fruit and play musical instruments, surrounded by blossoming flowers. The painting is not just a leisure scene, but also an image for religious meditation, dense with Christian symbolism such as the slayed dragon of evil and the fountain, source of spiritual life and salvation. The physical arrangement of the Renaissance garden bore a close resemblance to a stage set, a similarly enclosed and contained area for playing out fantasies and dramas, a source of transformation, dream and fantasy. However, while the early garden emphasised small-scale, enclosed spaces, later ones took inspiration from the open expanse of the Biblical wilderness. The opposition between garden and wilderness reflected man’s complex relationship to nature, where an impulse to shape, tame and control the natural world lived alongside a desire to yield to its wildness and danger – a duality that has shaped and influenced the way gardens have been visualised, both in life and art.

This is best seen in the eighteenth century. Following the example of the classic landscape artists such as Claude Lorrain and Poussin, British painters such as Richard Wilson, Joshua Reynolds and J.M.W. Turner moulded, refined, and ordered nature into stylised Arcadian scenes. Here, nature is the backdrop for the dramas of man, artfully tamed and idealised according to the pastoral model of classical literature. Richard Wilson was probably the best known exponent of this genre in Britain, painting many country house landscapes, such as Wilton House from the South East 1758–60. But despite the contrived quality of these landscapes to the modern eye, a new interest in naturalism emerged in the dawn of the Romantic era. ‘Nature’ was the new ideal, symbolic of an innocence and purity free from the vanity and corruption of man – untamed, and therefore untainted.

Taking their cue from painting, eighteenth-century landscape designers drew up ambitious plans for the physical alteration of nature. ‘Improvers’ such as William Kent, Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown and Humphry Repton (all of whom begun their careers as artists) used classical landscape paintings as their templates. The word ‘landscape’ became an interchangeable term for either a planted scene or a sculpted parkland, and the idea of the ‘prospect’, a bird’s eye view of the garden that derived from picture composition, was introduced into the gardening lexicon. This age of ‘picturesque’ design gave birth to the dramatic parklands of country estates such as Stourhead, Stowe and Blenheim Palace, where grand vistas sweep down to man-made lakes, only to rise up again to classical follies or fountains. And the ‘wilderness’, an area of wild woodland within a sculpted parkland, became a trademark of fashionable design. This inverted the tradition of the wilderness being a contrast, rather than a complement, to the Garden of Eden and brought it within the enclosed and cultivated garden.

While these gardens were like stage sets, they also had more practical, social functions, offering clear demonstrations of wealth and status. It is not surprising, therefore, that many artists were commissioned to paint these “stages”, often with the proprietor as the central protagonist. One of the earliest examples of this in Britain is John Michael Wright’s The Family of Sir Robert Vyner 1673, in which the physical extent of his formal garden can be glimpsed in the background, replete with statuesque putti and grand gateway. It was a clear signal not only of Vyner’s cultivation and taste, but also his wealth, power and status, implied by his ability to subdue nature. This convention has continued to the present day, tracing a line through the landscape backdrop in Thomas Gainsborough’s Mr and Mrs Andrews 1748–9 to the stylised settings of Hello! magazine photo shoots.

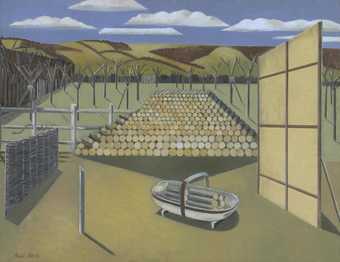

Paul Nash

Landscape at Iden

(1929)

Tate

During the Romantic era, however, the garden became seen as a worthy subject in its own right. Naturalism and realism were combined with the garden’s traditional function as a religious or social symbol. In Samuel Palmer’s In a Shoreham Garden 1829, a mysterious female figure wanders in the background of a domestic garden. A blousy pink blossom tree crowns a scene abundant with produce and flowers, painted with light, loose brushwork. The painting is a believable image of a real garden and yet, by drawing on traditional depictions of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, Palmer imbues the ordinary scene with a sacred atmosphere. Palmer’s mystical depictions of nature had a profound influence on subsequent artists such as Stanley Spencer, a key figure of the Romantic revival of the first half of the twentieth century.

Like Palmer, Spencer used familiar, domestic subject matter as a vehicle for profound religious or mystical meditation. Gardens often feature in his works, and he set several early Biblical scenes in his home environment at Cookham in Berkshire. In Zacharias and Elizabeth 1913–14 Spencer represents the story of the Archangel Gabriel’s visit to the priest Zacharias to inform him that his wife will conceive a child through God, foreshadowing the Virgin birth. He sets the scene in the context of an afternoon’s gardening in the home counties – with different figures mowing, pruning and clipping around the protagonists. A strange, gleaming white wall in the foreground enfolds the figures into a modern-day hortus conclusus, drawing conspiciously on the traditional symbolism of the virginal close-locked garden.

A few decades later, Paul Nash also adopted the garden as a talismanic symbol in his work. For Nash, the garden represented a place where man and nature meet, a subject which fascinated him throughout his career. At the time when he painted Landscape at Iden 1929, he was experimenting with the avant-garde styles of abstraction and Surrealism. The conflict between geometric order and uninhibited dream imagery collides in this picture, which seems to meditate on the traditional opposition between wild nature and the ordered garden. An orchard of regimented, closely pruned trees fills the background, and in the foreground various enigmatic fence structures enclose a pile of chopped wood and a basket holding logs. But although the title makes a pun on Iden/Eden (there’s even a snake in Nash’s picture), it is clearly no paradise. The felled, chopped and pruned trees in Landscape at Iden present an image of nature that Nash felt had become denatured – a powerful and disillusioned postscript to his First World War canvases of desolate, broken tree stumps, metaphors for fallen soldiers on the battlefield. For Nash, the garden was an emotional space which had profound personal resonance.

Many contemporary artists have since focused on the subject of the garden obliquely, seeking out the marginal or incidental manifestations of nature, such as the roadside weeds, overgrown back gardens or flowers sprouting unexpectedly from concrete. In Michael Landy’s recent etchings of common city weeds, each arbitrary and transient sprout is lovingly rendered with filigree delicacy and care, but they are presented as themselves, with no context. Where gardens are represented directly, artists often focus on formlessness rather than structure. Lucian Freud’s magnificent, almost photographic paintings of London back gardens present the same bleak candour about the appearance of nature in the modern world as his depictions of the naked human body. Although Freud’s use of indoor plants in portraits seems to symbolise the wild within the domestic, in Wasteground with Houses, Paddington 1970–2 the garden is neither cultivated, nor run wild, neither formal enclosed space, nor wilderness. The tangled overgrown plants merge and marry the twisted metal and refuse, creating a mongrel scene of ugliness and neglect, a sharp contrast to the organised brick and paintwork of the elegant townhouses behind. Freud’s gardens, like his bodies, are memento mori, reminders of what once was, or what could have been.

Wolfgang Tillmans

Lily & Oak 1999

Photograph

Courtesy Maureen Paley Interim Art, London © Wolfgang Tillmans

Art of the garden today has lost the traditional religious symbolism and social agenda that informed the imagery of the past. However, gardens and parks remain the primary point of contact with nature for many people, and therefore still offer fertile subject matter for the ongoing debates about man’s relationship with the natural world. In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida, the title of the exhibition at Tate Britain by Angus Fairhurst, Damien Hirst and Sarah Lucas, is a verbal corruption of ‘in the garden of Eden’, and the show includes several works that muse on the idea of a lost paradise. In Hirst’s latest diorama The Collector 2003–4, an animatronic figure of a botanist/collector examines butterfly wings under a microscope, while flowers bloom and butterflies flutter about him. Hirst demonstrates, once again, that imprisoning, controlling and destroying are unavoidable aspects of human contact with nature.

Perhaps Wolfgang Tillmans’s evocative Lily & oak 1999 remains the best example of today’s garden; a modern-day hortus conclusus which shows the persistence of wild nature within the confined, inhospitable space of a typical urban window-box. This incidental Eden makes no grand religious or social claims, but offers instead a simple image of hope and beauty.