Marcel Broodthaers (1924–1976) decided to become an artist only at the age of 40. Previously he had lived as a freelance writer in Brussels and Paris, publishing various volumes of poems and art criticism. On the invitation card to his first exhibition in 1966 he revealed the reasons for his change of career:

I asked myself if I couldn’t sell something and succeed in life. That was a moment when I felt good for nothing. I am forty years of age. The idea of ultimately inventing something insincere crossed my mind and I set to work immediately. After three months, I shall show my production to Edouard Toussaint, the owner of the Saint Laurent gallery. ‘But it’s art,’ he said, ‘and I will gladly exhibit all that.’ ‘Okay,’ I replied. If I sell something, he will take 30 per cent. These appear to be the usual conditions.

Broodthaers’s hugely productive and varied artistic work was created in the space of just twelve years. Especially in the last two years of his life, when he was already clearly dying, he opened up contemporary art in a poetically political way, and with a serious humour that is as relevant today as it was in the mid 1970s. He devised an unanticipated responsibility of form, which, though singular, nevertheless set new standards for what art could be. In his own words, he saw his practice as an ‘authentic form of questioning art’. And he worked on this in the knowledge that artistic activity, right from the moment of its reception and circulation in the art business, represented the ‘peak of inauthenticity’. The forms of particular negation by which he opposed this were characterised for him in that ‘on the level of the work, they contain in themselves the negation of the situation in which they find themselves’. Thus Broodthaers ‘made himself instruments in order to understand fashion in art, to follow it, and finally to find a definition of fashion’. In the process he discovered, among other things, the fashion structure of art, the eternal recurrence of the new. Within this structure, which also guides the art business, he felt his critically poetic practice was ‘guilty within ‘art as language’ and innocent within language as art’.

A good example of his poetically political view of art was Décor: A Conquest by Marcel Broodthaers, made at the ICA in London in 1975, six months before his death. It was an untypical work – both in the way it was made and in its site-specific arrangement, a feeling made more apparent when he stated its theme as ‘the relationship between war and comfort’.

Marcel Broodthaers

Décor as it was originally installed at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London 1975

Detail

Photo: Maria Gilessen © DACS 2008

Décor contains no works actually made by Broodthaers, consisting exclusively of objects which he and, on his behalf, the curator of the exhibition borrowed or bought. With these, the artist staged, in the form of two rooms, encounters between weapons and items of furniture that articulate the theme – the relationships between war and comfort, between the implements of war and pieces of furniture as symbols of power – in geometrically and austerely symmetrical arrangements.

In Salle XIXe Siècle there are two cannon in the style of Waterloo, an old revolver, a cannonball in the form of a ball of flowers, palms, Napoleonic chandeliers, Edwardian chairs, a large snake on the point of striking, two schnapps barrels, over which hangs a film still from the Western Heaven with a Gun and a card table on which a large crab and a lobster are playing cards. The objects stand either on plinths or on rectangular areas of artificial grass. The whole thing is illuminated by white, red and green spotlights. The scenario conveys the impression of a forgotten film-set, the deathly silence of an historical still life – a film-set full of bygone imperialist symbols of war culture and living culture: bygones, yet full of momentous consequence reaching down to the present day.

The Salle XXe Siècle, illuminated by a red spotlight, is, in the spirit of the times, more effective, more pragmatic, more banal, more brutal, plainer: in other words, more modern. There are appropriately modern weapons, revolvers, a hand grenade and various machine guns, the illustrated description and user’s manual for a German Luger pistol and an ensemble of garden furniture, including a sunshade: a scenario that suggests twentieth-century war technologies controlled remotely from comfy patio chairs. But all the weapons are fakes. And lying on the garden table as a counterpart to the Salle XIXe Siècle is a half-completed jigsaw of one of the historically most portentous battles of the nineteenth century, the Battle of Waterloo, after a print by William Heath.

Décor is not, however, an ‘installation’, at least not according to Broodthaers, who rejected installation as an art form. For him, it bore too many features of integration in, and adaptation to, the particular ambience and institution in which it was staged. He felt that his work was not integrated, nor did it adapt. Instead, it occupied a space with a form that stood for itself and critically distanced itself from its surroundings. In fact, he used Décor, which in French means both theatre and film-set, as precisely that – as the backdrop for his film The Battle of Waterloo, which he made during the exhibition at the ICA. This film consists of sequences intercutting between views of the exhibition and external shots of the Trooping the Colour, which takes place annually to mark the Queen’s birthday and passes outside the ICA. The internal views include the two rooms and details of Décor, but also feature the hands of an actress – first hesitantly, and then more quickly – disassembling a completed jigsaw puzzle depicting the Battle of Waterloo. The images are accompanied by the sounds of the parade ground and regimental bands alternating and overlapping with Richard Wagner’s overture to Tristan and Isolde. The film is not a consequence but the very purpose of Décor, which Broodthaers on the one hand understood as a free-standing sculptural occupation of an institutional space, and in this sense as a ‘conquest’ (an artistic Waterloo?) – in other words occupying an institution in a way that is not just decorating it – and on the other as a real film-set: not an end in itself, but rather what he described as a ‘useful object’, serving as means and content for a film. Broodthaers talks of the ‘Décor intention’, the specific intention, in other words, of restoring the artwork to its status of decorative object with a real function for something else. To shape rooms in an ‘Esprit Décor’ (as Broodthaers put it) did not mean, for him, establishing the object (or the painting) as a self-referential object that takes on its artistic character through its sheer uselessness, but rather restoring it with a ‘real function’.

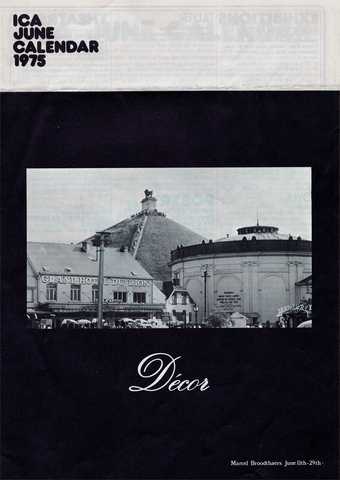

Bulletin of the ICA with a photograph of the monument at Waterloo, Belgium

Courtesy Tate Archive © ICA

As in almost all of his works, here Broodthaers confronts the presentation of meanings and the presentation of forms in such a way as to make them question each other. His ‘Esprit Décor’ stages a system for the interpretation of silence, which, in the midst of the staged decor, feeds us voids, intangibles, non-identities and a great deal of serious poetic humour. He never exhausts himself in negation. He never contents himself with illustrations of institutional and art criticism. All these features of particular negation happen with respect to ‘the construction of an abstract form’ which, standing for itself, carries within itself, sublimated, what is at stake in art and real life. In the case of Décor, the furnishing of an artificial room with borrowed weapons, seating and decorative objects becomes like an abstract form – a sense intensified not only by how Broodthaers saw it, but also by how visitors choose to interpret the piece. In this way Décor is Broodthaers’s sculptural conquest of an institutional space, whose history, function and context it both reflects and criticises with respect to its theme: the relationship between war and comfort.