The everyday is not selling well in the art world these days. People are more interested in the strategies of the market than in tactics of survival. The difference between a strategy and a tactic in this context was described very well in Michel de Certeau’s The Practice of Everyday Life (1980). A strategy, according to de Certeau (a Jesuit turned social scientist), relates to a form of authority that is capable of producing laws and commercial goods, including art and culture. A tactic, however, belongs to those people who defy authority and infiltrate institutions, but do not wish to take them over. The art world has always reflected this dichotomy between strategies and tactics in the production of art. When its economy is strong, most of the subjects – artists, curators, collectors, dealers – follow strategy’s path. But when that economy collapses, the surviving subjects move into a more tactical sphere, embracing new methods of production in ephemeral situations and courting the everyday more than the permanence of art history through the object – be this a painting or a sculpture, photograph or video installation.

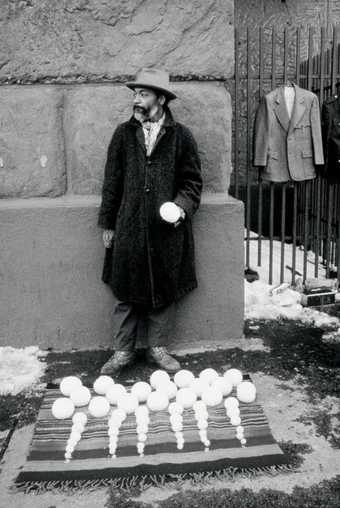

David Hammons performing Bliz-aard Ball Sale 1983, Cooper Square, New York City

Photo: Dawood Bey

Courtesy Migros Museum, Zurich © David Hammons

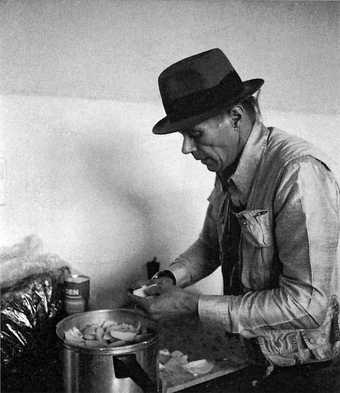

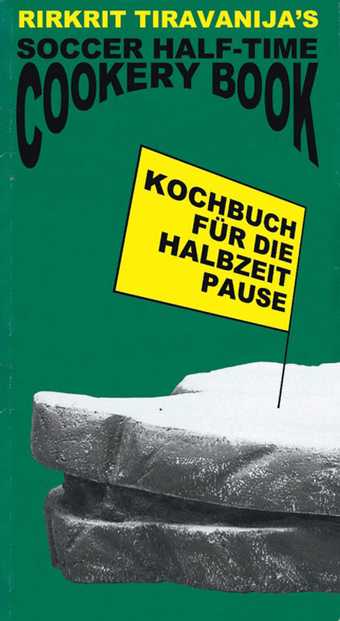

Looking back, the return to painting emerged out of the economic doldrums of the 1970s, typified in the work of the German neo-Expressionists (such as Anselm Kiefer), the Italian transavantguardia (Francesco Clemente, Enzo Cucchi), or individuals such as Julian Schnabel. All represented a rejection of the collective mood of the anti-object work from the 1970s. And the generation of artists that emerged after the Black Monday crash in the financial markets in 1987 reclaimed the carpe diem motto, creating art as a way of living rather than a production of objects. The appearance of an artist such as Matthew Barney, who would later become a darling of the collecting establishment, reflected the necessity for this generation to define a new territory. His early performances, such as Drawing Restraint 1–6 1987–9, in which he climbed around his studio or gallery walls, attempting to create drawings while hindered by obstacles and various objects, were entropic actions that transformed the everyday obsession with the body of the late 1980s into a quasi-escapist practice from the imploding hedonistic atmosphere of that period. Another artist of the same generation, Rirkrit Tiravanija, in his debut show at 303 Gallery in 1992, offered another alternative to the strategies of the art market – transforming the selling point of the gallery space into a service for the visitor. His revolution was to dispose of the artist as hero to create the artist as host. If Joseph Beuys embodied the ambiguous role of the healer, Tiravanija aimed at a more practical position, for example turning the gallery into a restaurant and offering each visitor a meal.

Joseph Beuys cooking stew in his Düsseldorf studio 1984

Photo: Lucrezia De Domizio Durini

Courtesy Edizioni Charta, Milan

Rirkrit Tiravanija

Soccer Half-Time Cookery Book 2006

Cover

Courtesy Verlag für Moderne Kunst Nürnberg © Rirkrit Tiravanija

Following his Buddhist roots, the Thai artist believed in a practice that focused on the process or the path rather than the goal of historically strategic art object. We could trace his influence back to Marcel Broodthaers, even if the Belgian was moved more by need than by necessity. Broodthaers was seeking a form of artificial historicity rather than a straightforward celebration of the everyday. But Tiravanija was not alone in drawing a new map of the everyday. Around the same time other artists such as Gabriel Orozco, Philippe Parreno, Ceal Floyer, Koo Jeong-a, Maurizio Cattelan, Sarah Lucas, Carsten Höller, Yutaka Sone and Udomsak Krisanamis started to explore the possibility of morphing the everyday into a new form of art. Orozco’s Empty Shoebox 1993, first shown at the Venice Biennale on its own in a room, is maybe the ultimate and most symbolic gesture to reduce the monumentality and self-celebratory attitude of Minimalism into its very opposite: a monument to now. In all Orozco’s early work the now and the everyday are glorified in their momentary existence. The artist’s breath on a piano (Breath on Piano, 1993), oranges on empty market stalls (Turista Maluco, 1991), wet tyre marks left by a bicycle, the empty shoebox… all carry the universal message of life = art.

Gabriel Orozco

Extension of Reflection 1992

C-print

40.6 x 50.8 cm

Courtesy Marian Goodman Gallery, New York © Gabriel Orozco

The everyday is, for the artists of the 1990s, the new eternity. Their motto could have been: ‘Now is for ever’. The granddaddy of the everyday generation is David Hammons, who mastered the practice long before those artists mentioned above were out of their nappies. From his Bliz-aard Ball Sale 1983 – selling snowballs of different sizes on Cooper Square in New York – to distributing a simple weather forecast (‘August 18th in Munster: it will rain’) passed by word of mouth, the everyday is transformed into the only day. The Hammons ‘children’ conceded to some form of strategy, with the increasing pressure of the art market and the temptation to move the bareness of the mundane into major elaborated productions changing the platform of everyday reality into some kind of theatrical fiction. Meanwhile, Hammons maintained the integrity of his own tactics, moving guerrilla-style among the treacherous sirens of the twenty-first-century art world. Tiravanija and company had harder times in maintaining their ground.

One of the most innovative artists of the everyday group – if you can call them that – is Olafur Eliasson. After his masterful installation The Weather Project 2003–4 at Tate Modern, where he prolonged the end of the day with his artificial sun (and at the same time injected a level of mysticism rarely seen in contemporary art), his most recent project imploded through over-production. New York City Waterfalls – four artificially constructed waterfalls ranging in height from 90 to 120ft, installed at sites along the banks of the East River – cost $15million and seemed like a fiasco. The water being pumped out of the pipes looked more like a giant leak than the natural wonder we were expecting; and the salt water spray threatened to kill off some of the local plant life. Those pipes reflected the crisis within a generation apt to mishandle their ability to construct a consistent philosophy about the everyday and lost in the over-arching scale of their projects. Simplicity transformed into a Fitzcarraldo-esque nightmare.

The remake of the everyday appeared much more difficult, complicated and expensive than any of the artists involved in the early process could have ever imagined. From the studio to the restaurant to the street and into the factory – this is the progression that many artists have followed, with the everyday becoming a business in between architecture, the movie industry and the theatre. Duchamp would have done it more elegantly – a chess game in a museum or a nice walk across Washington Square. His attitude was mirrored at the beginning of the 1990s but today has largely disappeared. Even Tiravanija’s performances have lost some of the freshness that pervaded the space of his early cooking experiments. Today his conviviality happens in more structured events for more strategic circumstances. The sensibility of Orozco’s exhibition of four yoghurt carton tops at the Marian Goodman Gallery in 1994 was evoked by his latest installation Obit 2008, made up of drawings and collages of obituaries from the New York Times. Cut-and-pasted anecdotal stories of the deceased attempt to grasp the everyday in the same way that the yoghurt cups did, but finally they cannot compete with that blunt gesture raised from pure necessity.

Matthew Barney

Performing Drawing Restraint 2 in his studio 1988

Photo: Michael Rees

Courtesy Gladstone Gallery, New York © Matthew Barney1988

The everyday has become an exclusive club, losing a big part of its capacity to absorb the social realm within its boundaries. Only those who never belonged to the club are today still in the trenches of the everyday, the Swiss duo Fischli & Weiss, Martin Creed and Jeremy Deller. These artists have been able to maintain the balance between processing the moment and producing a substantial artwork. Former outsiders such as Roman Ondák or Pawel Althamer are also preachers of the everyday as the only way to seek inspiration in their creative endeavour. Yet even their stubborn form of resistance is softening. The art world, as with all well-oiled capitalist systems, understood long before the practitioners themselves that the everyday was a form of subversion that needed to be framed in order to limit its possible effects, influence and eventual damage. Because the everyday tactic manifests itself not in its product but in its methodology, the art world offered the artists the chance to enhance their production methods, thereby weakening their subversive tactics. Lured by the opportunity to make their interventions more visible and permanent, many artists abandoned daily experimentation, and with it part of their free soul. Most of them knew from the very beginning that this would be the outcome. Few used the everyday as a Trojan horse to infiltrate the market and take economic control of their own production. Few, if any, stood apart. Those who did, such as Christian Philip Müller, are not as visible as they might be. The everyday rarely sells, unless it is presented like a lacquered vitrine of cigarette butts. Art, after all, is all about transforming the everyday into something exceptional. It should not come as a surprise that what came out of necessity at the beginning of the 1990s after a brutal economic downturn, was then transformed into a conventional strategy. It is a matter of logic – the coming of age of any subversive movement. Today we are facing another economic meltdown and, in its wake, a new form of artistic resistance will probably surface in the next few years. Galleries will change their spots once again, presenting themselves as born-again restaurants, bars or community centres. Tactics of survival will once again replace more structured strategies. Art practice will probably free itself again from grounded institutions to avoid the risk of being archived too soon as a period’s token in museums’ collection storages. The everyday will regain prominence. In fact, Michel de Certeau pointed out that in its slipperiness lies a good deal of the everyday’s power.

Martin Creed

Work No. 925 2008

Various chairs

188 x 55 cm

Courtesy Hauser and Wirth Zurich © Martin Creed

When sixteen years ago I crossed the threshold of what I used to know as 303 gallery to enter Rirkrit Tiravanija’s made-up noodle restaurant, I did not know what I was looking at, but I felt the strength of a powerful new language. It was a lesser god revolution, but still a revolution. Crisis, as painful as it can be, can help the language of art reconfigure itself. But we must keep in mind that yesterday begins tomorrow and so it does everyday.