Valentine de Saint-Point (1875–1953), formerly a model for Alphonse Mucha and Rodin, began her life as an artist desired by two important Italian leaders of the avant-garde established in Paris. By 1904 she lived with Ricciotto Canudo, director of the reviews Europe Artiste and Monjoie! (crucial for Cubist studies) and future author of the Manifesto of Cerebrist Art. By 1905 she had met F.T. Marinetti, director of the review Poesia and future author of the Manifesto of Futurism. The core of her work was developed in these early years of brainstorming before the explosive period of manifestos from 1909 to 1914. Her thoughts were enriched as she interacted with two visions of modernity: Canudo’s, more conceptual, eroticised and sensual, and Marinetti’s, more destructive, provocative and energetic. Art historians have never been aware of the importance of this love triangle in the emergence of the avant-gardes. They preserve Marinetti in divine isolation, proclaiming the birth of Futurism as a one-day big bang event that happened on 20 February 1909 and was published in the Parisian newspaper Le Figaro.

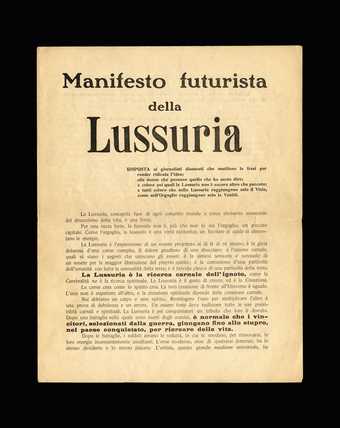

The theories Saint-Point developed with Canudo through Cerebrism (cerebral + sensual art) were not object-orientated, they were the ultimate level of evolution of the arts after centuries of academic disciplines. This artistic positioning can be better understood today, since we are familiar with disciplines such as Conceptual and Performance art. Her work is marginalised in most exhibitions on Futurism, as they are structured around the hegemony of painting and sculpture. If she is deemed to merit a mention, she is often reduced to an appearance in the chronology, where she is cited in 1912 and 1913 for her Manifesto of Futurist Women and her Futurist Manifesto of Lust. The ideological rallying cry in the latter, ‘we must make lust into a work of art’, produced no identifiable art object. Rethinking Futurism calls for new curatorial strategies where concept-orientated work can find an adequate space of display.

Art historians note the composition of the Direction of the Futurist Movement document, but never notice the real revolutionary aspect contained within it. The statement was divided into five sections: ‘Poetry’, ‘Painting’, ‘Music’, ‘Sculpture’ – all forms of art heavily rooted in the classical past – and then a strange discipline appears on the page, ‘Action Féminine’, represented only by ‘the poetess Valentine de Saint-Point’. We can surmise she invented this notion in contrast to the term feminism, introducing its equivalent into the field of the arts with an innovative and provocative artistic strategy. Establishing this first step, Saint-Point was able to reach realms that no other feminists had done at that time. Reversing centuries of hegemony of the ‘Spirit’ and ‘Mind’, she considered the ‘Art of Flesh’ and the ‘Art of Lust’ to be equally important and anticipated their own field of artistic creation. More than ten years later, her experiments with what would become known as Surrealism, eroticism and sexuality came into their own. Her Manifesto of Lust strikingly anticipates key aspects of Surrealism:

Lust, conceived beyond moral preconceptions and as an essential element of the dynamism of life, is a force.

Lust is not a sin. Like pride, lust is a virtue that urges one on, an epicentre at which energies are resourced.

Lust is the expression of a being projected beyond itself.

Lust is the carnal quest for the unknown.

Lust is the act of creation and the creation as such.

Flesh creates as spirit creates. Within the scope of the Universe, their creation is equal. One is not superior to the other, and spiritual creation is not independent from carnal creation.

We must face lust with awareness. We must make of lust what a refined and intelligent person makes of himself and of his own life, we must make lust into a work of art.

Futurist Manifesto of Lust, 1913.

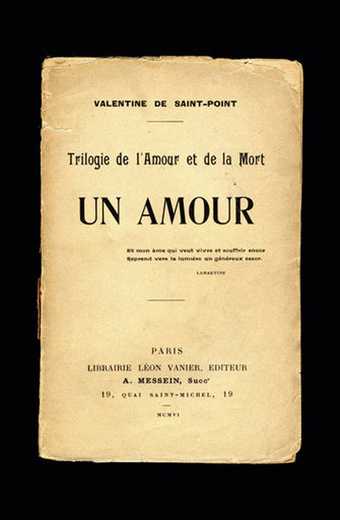

In her early publications A Love 1906 and A Woman and Desire 1910 Saint-Point explored the feminine psychology of desire, at a time when feminine sexuality was still defined by Freud in terms of ‘castration’ and ‘lack’, compared with male sexuality. In her Manifesto of Futurist Women she criticised feminists seeking the same rights as men, arguing that this would lead only to an excess of order, not to the shifts and disorders that Futurists claimed. Instead, she provocatively invited them to be more imaginative, to ask for more unequal rights, even superior or more cruel ones:

Woman, become sublimely unjust once more, like all the forces of nature! Delivered from all control, with your instinct retrieved, you will take your place among the Elements.

The manifesto is structured as a reply to Marinetti’s provocation in Founding Manifesto of Futurism, 1909: ‘We wish to glorify War – the only health-giver of the world – militarism, patriotism, the destructive arm of the Anarchist, the beautiful Ideas that kill, the scorn for woman.’ Saint-Point diplomatically introduces her criticism, explaining that women and men equally deserve the same scorn, that the whole of humanity is becoming mediocre. She also recalls, concerning the issues of war, that woman warriors ‘fight more ferociously than men’, referring to the Amazons, Semiramis or Joan of Arc.

She goes further to set up a broader historical analysis of human civilisations: ‘It is absurd to divide humanity into men and women. It is only composed of femininity and masculinity.’ She observes that the periods of history dominated exclusively by masculinity were sterile, brutal and had only wars. The periods dominated exclusively by femininity were turned towards the past and annihilated themselves in fantasies of peace. ‘The fecund periods, when the most heroes and geniuses come forth from the terrain of culture in all its ebullience, are rich both in masculinity and femininity’ After the elaboration of this sensibility of balance and equilibrium, which characterises her thoughts during her whole life, she is back to more supportive sentences for Futurists: ‘We are living at the end of one of these periods. What is most lacking in women as in men is virility. That is why Futurism, even with all its exaggerations, is right.’ But this support publicly ended in 1914 when she left the movement and its violence.

She had already analysed the psychology of violence and excess within the terms of an eroticised and sexualised political power, in her modern tragedy The Imperial Soul - The Agony of Messalina. This play was staged in 1908 and then published with a statement of theory in 1926. An intimate landscape of lust, force, desire and despair is depicted through the powerful words of the Empress during her death agony:

Once more I will see you pale from voluptuousness

Or from the obscure desire of my hot beauty

Once more I will exhaust your sons, your brothers,

Your lovers, your husbands!

My insatiable flesh still reigns over all…

As an aspect of her ‘Art of Flesh’ Saint-Point initiated a new cross-media performative form of art that she called ‘metachory’, a combination of Greek words meaning beyond the dance. The first metachory was staged in Paris in 1913, with a theoretical explanation, after which she performed a solo almost naked, her body partly veiled by transparent silk strips. Her face was veiled in order to focus the audience’s attention on the abstract and geometrical aspects of her dances and not on emotions, since Futurists rejected sentimentality. Her movements were combined with words from her Poems of War and Love, light projections of mathematical equations and an effusion of perfumes. The music was disconnected from the gestures. As opposed to other dancers of her epoch, such as Loie Fuller or Isadora Duncan, she wanted neither dance that expressed the emotions of the music, nor music that expressed the emotions of dance. She separated them as two autonomous layers in interaction, anticipating the experiments of composer John Cage and choreographer Merce Cunningham years later in America in the 1950s. Innovative composers who created music for her included Claude Debussy, Roland Manuel, Dane Rudhyar, Erik Satie, Maurice Droeghmans and the Futurist Francesco Balilla Pratella. The Metachory Festival she staged in 1917 at the Metropolitan Opera House, New York, introduced American audiences to her polytonal and dissonant music.

In the later period of Futurism, Marinetti extended his lyricism of war to the support of fascism and his friendship with Mussolini. Saint-Point developed several unrealised political projects, including the collaboration entitled the ‘United States of Mediterranea’. She left France for Egypt in 1924, shortly after the death of Canudo. As an ultimate form of artistic positioning and feminine action, she bravely initiated political actions in Cairo against war, colonialism and injustice. Harassed by both French and British intelligence services, she was obliged to stop the publication of her review Le Phoenix (1925–7), which tried to reunite Christian and Islamic civilisations through art and culture. Her book The Truth about Syria (1929) contained an accurate geopolitical vision, anticipating the tragedy we are now witnessing in Palestine and Lebanon. In 1933 she functioned as a mediator in peace discussions between France and Syria – before the French army launched an attack that ended in a disastrous defeat. Valentine de Saint-Point died in Cairo in 1953, disillusioned but peaceful, inspired by the mystical serenity of Sufism and the desert. She lived her final years as a modern Lady Hester Stanhope, who, ironically, had caught the eye of Saint-Point’s ancestor, the French poet, politician and pacifist revolutionary Alphonse de Lamartine. His castle was situated in the village of Saint-Point, from which Valentine took her surname.